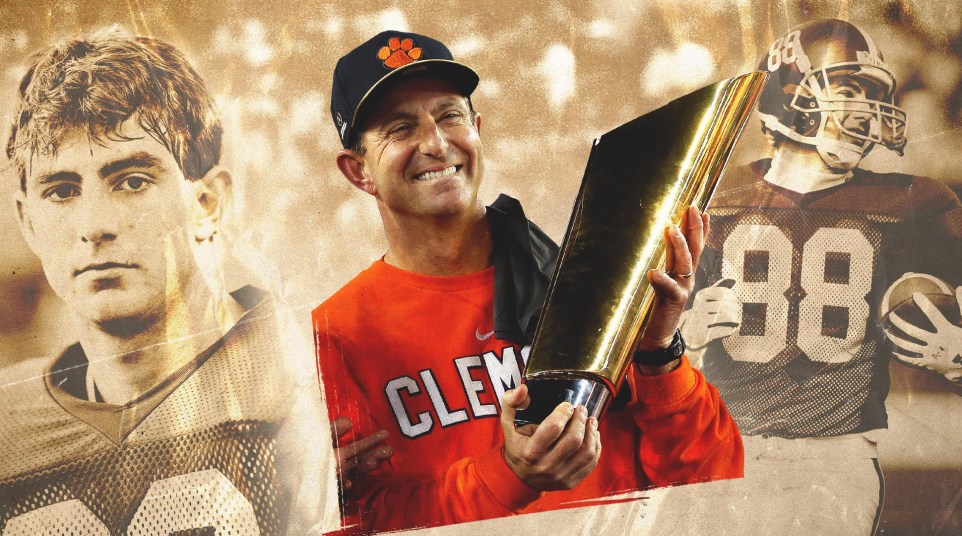

Built by Bama: How Gene Stallings and a national championship team shaped Dabo Swinney

Dabo Swinney didn’t leave Alabama behind. Just the opposite. From lessons to teammates, he took every part of it with him to Clemson — and built the next great college football giant.

Membership in the Alabama fraternity has its privileges.

Colby Key sat on the edge of his seat and watched an orange poker chip emerge from behind the desk drawer. The 10-year-old was in a place in which most kids his age are not afforded the privilege, but as a son of a former teammate, he was the exception to the rule.

Colby’s father, Chad Key, once played with a scrawny wide receiver who used to catch passes at the University of Alabama. After graduation, that receiver embarked on a snaking journey that began as a grunt for coach Gene Stallings, that detoured into the world of commercial real estate, and that finally arrived at the head coach’s office at Clemson University.

The former receiver’s name is Dabo Swinney.

That January day inside his office, Swinney held the poker chip between his fingers and stared past it at Colby, who twisted in his seat. Chad described what unfolded.

“I’m going to give you something, buddy,” Swinney said. “And I don’t give these to just everybody. It’s got ‘All In’ on it and I want you to be all in.”

Wide-eyed, Colby began nodding before saying, “Yes sir, yes sir.”

But Swinney needed further assurances from his young recruit.

“I’m not just talking about I want you to be All In Clemson,” he said. “I want you to be All In school, All In what your mama and daddy says, All In about being a good person, All In about doing what’s right … Do you think you can do that?”

Colby agreed. He would do it. He was All In.

“Now,” Swinney continued, “who do you want to win the national championship this year?”

“You coach,” Colby said.

Swinney smiled and handed him the chip.

“We’re fixing to go over here to practice,” he said. “I want you to go over by Howard’s Rock, run down, and I want you and your dad to go over there and throw the ball on the field. Y’all are staying at the house this weekend and I want you to have a great time and enjoy yourself. My house is always yours.”

Such is the case whenever Chad and Colby visit Clemson. The proverbial front door to Camelot is swung wide open, and Colby has access in which other kids can only dream.

The Crimson run

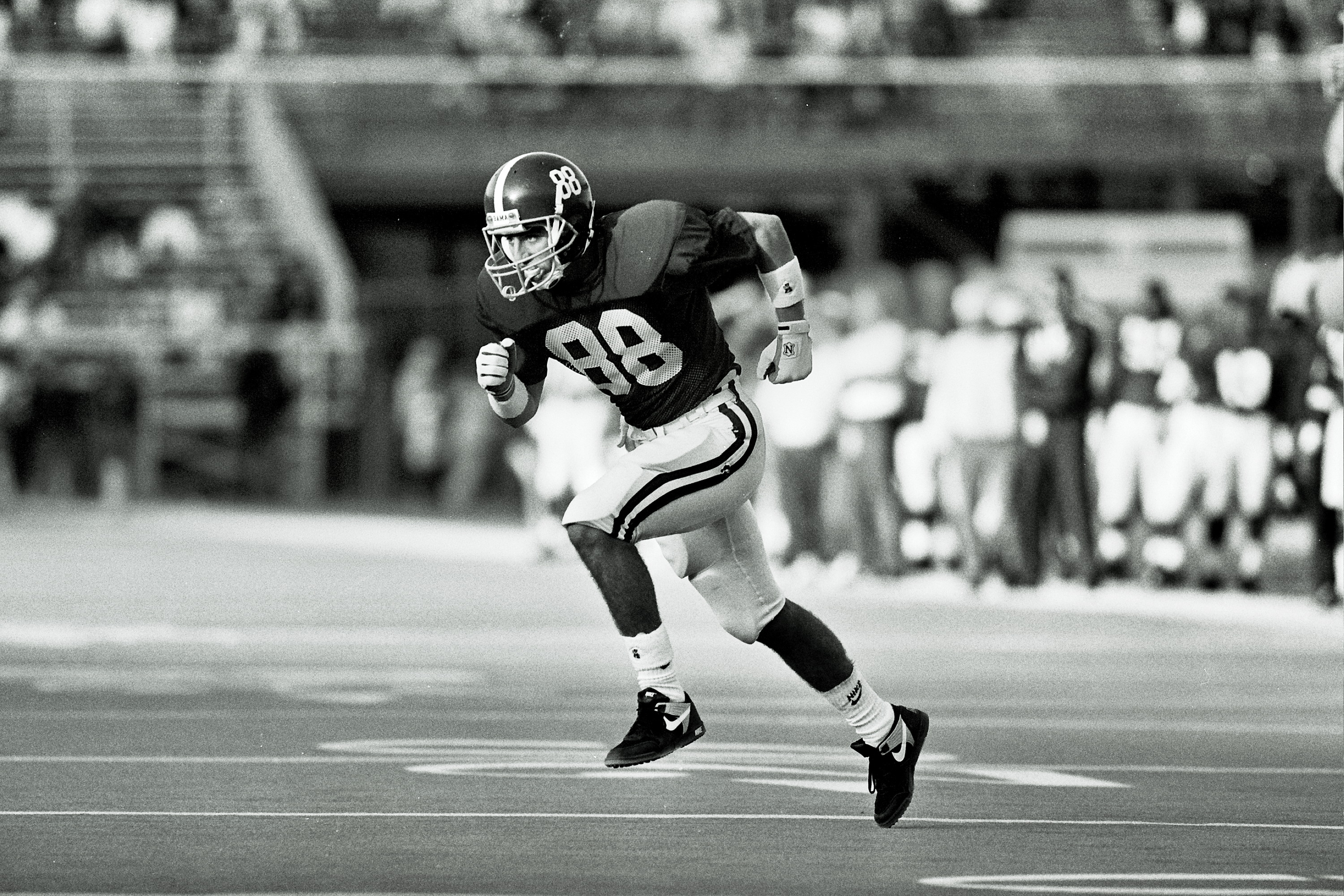

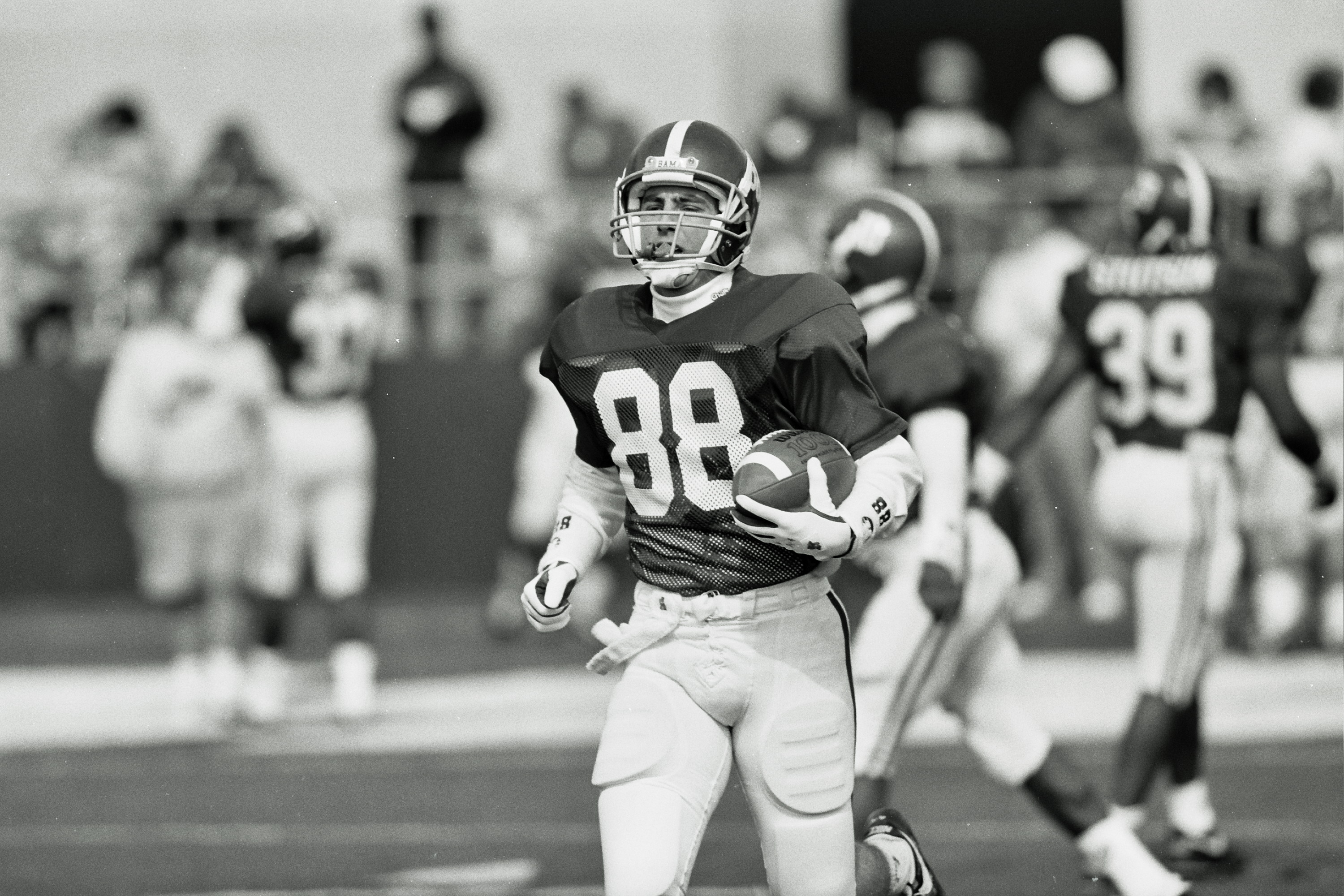

Former teammates say what Dabo Swinney lacked in size, he more than made up in ferocity. Photo by: Kent Gidley/Crimson Tide photos

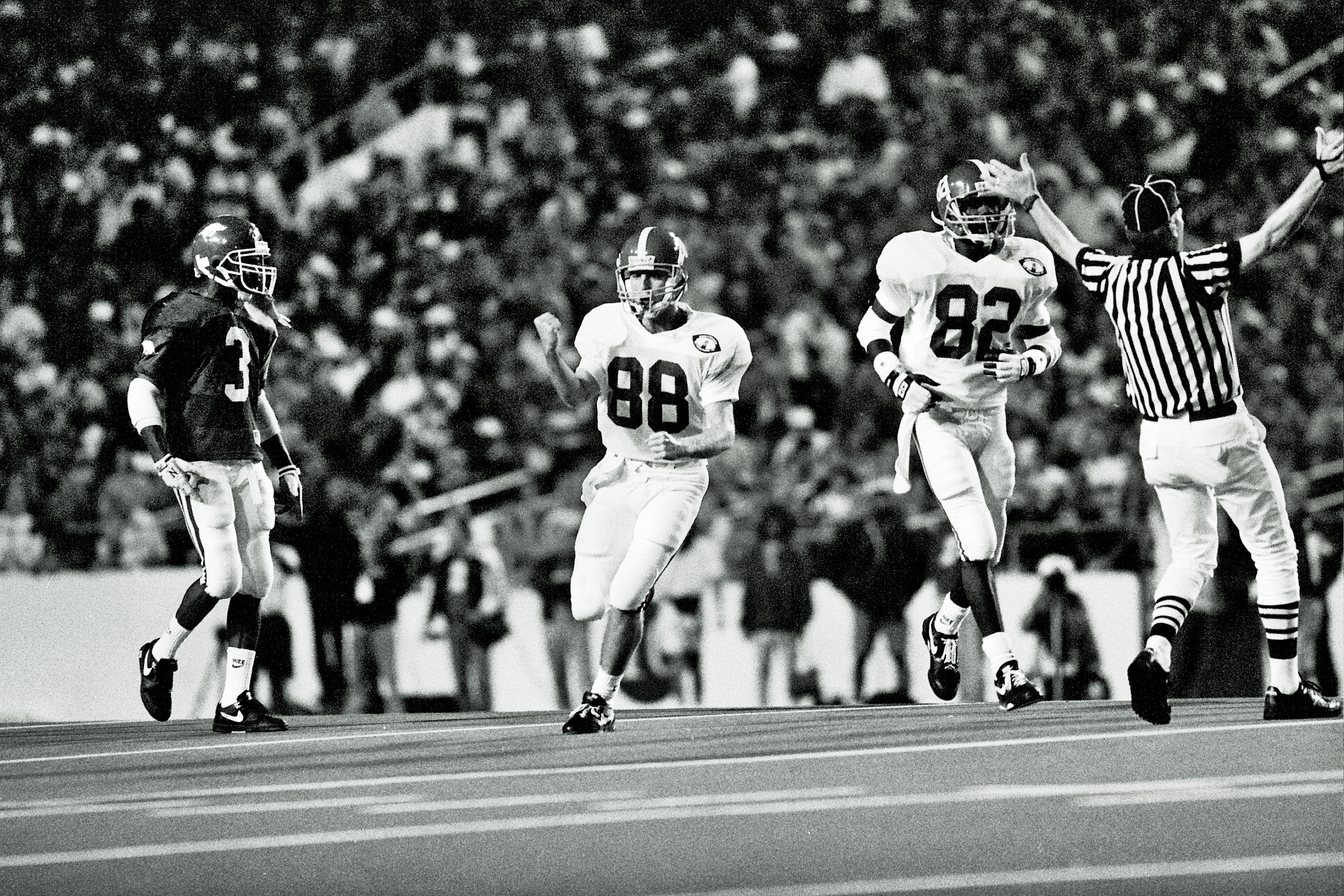

For a moment, let’s go back to January 1, 1993. Inside the Louisiana Superdome, Gene Stallings is riding to meet Dennis Erickson on the shoulders of his players. Alabama has just defeated the Miami Hurricanes to claim its first national championship in 13 seasons, and as the flashbulbs popped and Alabama’s tweed-jacketed coach lifted a celebratory fist, Chad Key and Dabo Swinney, both dressed in crimson, circulated the bedlam. The story in the paper the next day read 1-DERFUL, and indeed it was for a multisport athlete from Jasper and a little ol’ wideout from Pelham.

Unlike many of his counterparts, Key remembers the first time he heard that unique name, “Dabo.” Swinney, who was two years ahead of Key, made a lasting first impression during practice one day when “goods” were matched up on “goods.” In the early 1990s under Stallings, Alabama had became famous for utilizing the hell-for-leather play, the toss sweep, but from time to time it would use deception to its advantage and call a variation, including the toss sweep reverse. As the Tide was practicing this particular play, a defensive player (who will remain nameless) who loved to run his mouth was talking smack to the wide receivers. Perhaps all of that trash talk distracted him from a crackback block that was administered on him by a diminutive receiver wearing number 88. Yes, that’s right. Dabo.

“He didn’t see it coming and Dabo just blasted him,” Key said. “He’s standing over him doing that crank the chainsaw move. My first impression was, ‘who’s this cocky little guy named Dabo?'”

Eventually, the two men struck up a great friendship. Dabo became “Dab” and Chad, a fellow wide receiver, became “Mitts” because of his large hands.

When they weren’t winning national titles and going scorched earth through the SEC, Dab and Mitts would double date, play basketball, or go get something to eat. According to his teammates, Dab was more of a quiet guy — not sit over in the corner quiet, but certainly not the peacock-like personality filling TV screens today.

His intensity was never in question, however. Key recalls an exchange when he was playing pickup basketball against Dabo one day at Coleman Coliseum. Back then, Key was known as the ringer amongst his and Swinney’s group of peers. Key, who was 6-4, could shoot, drive, and jump out of the gym, and whomever had Key had a good chance to win. But Key remembers on this particular day, as Dabo manned up on him, “there was no back-down factor in his eyes.”

“I can remember he made a couple of buckets on me,” Key said. “And it’s the same mentality that he carries right now, that he wasn’t going to back down. Here we are 30 years later, and he goes to Palo Alto to play Nick Saban, one of the greatest college coaches of all-time, and there is no back down.”

And it’s the same mentality and fury for winning that bears itself in the occasional sideline meltdown — remember the undressing of punter Andy Teasdall on national TV in 2016 on a fake punt attempt that went awry? — in his snappy defense of his program after one of Steve Spurrier’s verbal zingers, and the unthinkable decision to bench starting quarterback Kelly Bryant in favor of true freshman Trevor Lawrence.

Swinney arrived on the Alabama campus in the summer of 1988 after graduating from Pelham High School. His Horatio Alger-like upbringing, chronicled in a 2016 article by ESPN’s Mark Schlabach, was far from idyllic. As the story goes, after his father, Ervil Swinney, found himself in a mountain of debt, he turned to the bottle for resolve. Eventually Swinney’s parents divorced and poverty required his mother to move into Fontainebleau Apartments in Tuscaloosa, where her son boarded for college. With roommate Alex Morton, it was the 80s version of Three’s Company — only with two boys and Swinney’s mom (and not Suzanne Somers) in the other room.

After a year without athletics in his life, Swinney eventually decided to do the college football equivalent of a meeting with Gordon Gekko: He would walk-on to the Crimson Tide football team. At the time, Bill Curry was steering the ship as the head coach at Alabama, two coaches removed from demigod Paul “Bear” Bryant.

“I remember (Dabo) when he walked into his first team meeting. He was there based on merit, not by invitation,” Curry told SDS.

As Curry recalls, strength coach Rich Wingo had implemented a grueling process for prospective walk-ons, structured so most would quit. But “Dabo would not quit, was one of three out of the 40 or so who began,” Curry said. “I do remember introducing him. I have great admiration for walk-ons and I think he sensed it.”

Swinney scrapped and clawed his way through that first year, eventually moving from scout team to travel team. Bryne Diehl, a punter on the team originally from the tiny hamlet of Oakman, noticed the precision in which Swinney and others attacked their job. “Him and Prince (Wimbley) and Craig (Sanderson) were out there on their own, and they were actually trying to come up with different schemes and different ways to run a route … that’s how meticulous he was,” Diehl said.

The ball rarely came his way, but Dabo Swinney worked on his craft as if he were the top target. Photo by: Kent Gidley/Crimson Tide Sports

During the offseason, Curry bolted for Kentucky and a new sheriff named Stallings swaggered into T-town. The Stallings-Curry juxtaposition was stark, and though Swinney was eventually awarded a scholarship by Stallings his junior year, that did not change his middling status on the football team. He never was known as an elite player — his 7 career receptions are the greatest testament to that fact — but by the 1992 championship game against Miami, he had ascended the toilsome stepladder from walk-on to starting wide receiver. No surprise: His teammates attributed that to his work ethic, attention to detail, and never-say-quit attitude.

Swinney listened to and did what Stallings said. In the process, he learned several lessons that transcended the locker room. He learned to be on time. He learned to do the little things well. He learned to surround yourself with good people. He learned to get a little bit better every day. He learned not to make excuses. And if you mess up, fess up.

Perhaps most important, he learned what it takes to build a championship football team.

After a 7-5 first season under Stallings, the Tide went 11-1 in 1991. And in 1992, they brought home the school’s 12th national title.

For Alabama, the championship was a culmination of many things. First, it got the monkey off its back for the program’s failure to deliver a national title in the post-Bryant era. It was also redemptive in the fact that Alabama had taken down Steve Spurrier’s Florida, which had throttled the Tide 35-0 a year previous in Gainesville, 28-21 in the inaugural SEC Championship, and then overcome Miami, the mouthy juggernaut of the previous decade that had foiled Alabama’s national title hopes in 1989, in the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans.

But perhaps even more than that, it was the overall journey that would make a lasting impact on the men. On Swinney, too. It was eking by Louisiana Tech on a cloudy day in Birmingham when the offense couldn’t seem to get clicking. It was a bare-knuckle showdown in Knoxville against the always-tough Johnny Majors-led Volunteers. It was overcoming yet another eerie night in Starkville, where things could have easily gone the other way against Jackie Sherrill’s Bulldogs. And it was the second half of a game in which Auburn really preferred the retiring Pat Dye to go out a winner.

In the final analysis, those were the games that truly mattered. Those were the games that shaped and polished the men, and that reinstated the Tide-ruled universe.

Stallings knew before Dabo knew

Stallings saw something in the boy and convinced him to hang around the program as a graduate assistant, which Swinney did in 1993. For the next two years, Swinney would pursue his M.B.A. and help out with the team while Stallings groomed him to be an assistant. That was a good thing for Swinney and players like Chad Key, who didn’t want to see his friend go.

In 1996, Stallings hired Swinney as a full-time coach in charge of wide receivers and tight ends. Stallings always looked for four things in an assistant, and Swinney checked all of the boxes. “First of all I look for a good person, and Dabo was definitely a good person,” Stallings told SDS. “I look for somebody that’s knowledgeable about the game. And he was knowledgeable. I look for somebody that has a good work ethic. And obviously he had a good work ethic. And somebody that can communicate with the player. And obviously Dabo can do that.”

Soon after Swinney was hired, he learned a valuable lesson about balance, which has become a story told many times over but also a philosophy he applies to his Clemson program even today. Late one evening, Stallings passed by Swinney’s office and noticed that the young coach was still working while everyone else had gone home. Expecting praise, Swinney instead was met with words of disdain, the steely-eyed Stallings looking down on his lieutenant as he offered something to the effect of, “You need to get out of here. You’ve got a wife at home and I don’t ever want to catch you here like this again.”

Three decades removed from that admonishment, Stallings added further clarification: “When I was coaching, I never did have night meetings. I felt it was important for the coach to have dinner at his house, around his table, with his children. And so that’s what I tried to do. There he was hanging around late, trying to get in a little extra work. And I felt like you need to be home with Kathleen. I just told him, I said, ‘Son, there’s enough time during the day. If you can’t get it during the day, then we are doing too much. You need to spend some time with your family.’ That’s the philosophy I had when I was coaching and it stayed with me throughout my coaching career.”

Stallings’ last hoorah came in 1996 and assistant Mike Dubose was tabbed as his replacement. Dubose elected to retain Swinney, who remained on staff inauspiciously until Dubose’s ouster in 2001.

Then Swinney shifted gears and got out of football altogether. Perhaps this coaching thing wasn’t what it was cracked up to be anyway. He rejoined Wingo, the strength coach who had become the head honcho at AIG Baker, a real estate development firm in Birmingham, as a salesman. For nearly two years, Swinney pedaled the grindstone to his sales skills and became, as writer Kent Babb noted in a well-written piece for The Washington Post, “the best shopping center leasing agent in Alabama.”

Sanderson, Swinney’s teammate who was also part of the receiver corps for Alabama, says that Dabo essentially recruited him to come to work for AIG Baker after a golf outing in Mobile. “Three months later, we were building houses next to each other at Greystone (development),” Sanderson said.

Through Wingo, the Alabama connection was still paying dividends, albeit in unanticipated ways.

Salesman with a whistle

This was a key rung in Swinney’s comeuppance and fertilizer for the full flowering of his personality. And who could have possibly known that the missing piece Swinney needed to become a top-level college football coach was found, not in the trenches of a coliseum, but out in the real world of briefcases and contracts? For if Swinney could sell space in a shopping center in the town of Olathe, Kansas, surely, surely he could sell a college football program with the historical significance and amenities of a Power 5 school.

And what was the secret of his success? The hustle on the asphalt. “Swinney attended business lunches and sent thank-you notes. He pressed business cards into hands at the annual shopping center convention and remembered names and faces. He studied traffic counts and demographics surrounding a project, learning the kinds of customers who’d shop at a particular complex and the kinds of businesses those customers would seek. He discovered the factors that mattered to a prospective tenant and drilled into that topic during his pitch: “You know you’re sitting here with a Super Target and a Bed, Bath & Beyond,” he would say in that mile-a-minute cadence of his, “and this is a space that we’re going to be able to get you a deal on,” Babb wrote.

Someone was noticing. Eventually Clemson and head coach Tommy Bowden called in 2003, and Swinney packed his bags to leave Alabama for the first time in his life. No worries, though. By the time he and his wife Kathleen hit the four-lane north, they had a carful of moxie and battle-tested faith as their cargo. As Bear Bryant might have said, “You never know how a horse is going to pull until he’s hooked to a heavy load,” and in the case of Dabo Swinney, that load had been mighty hard.

For five full seasons, Swinney slogged under the more stoic Bowden and drank up the elixir of football — Clemson style. Bowden appointed him wide receivers coach but also smartly put him in charge of recruiting. As a result, Clemson climbed from 66th in the country in recruiting in 2003 to 16th by 2006 (according to Rivals.com).

Change was a-comin’, but unfortunately Bowden never enjoyed the red meat of this recruiting push. His coaching seat perpetually set on warm, Bowden resigned surprisingly in October 2008 after a mediocre 3-3 start. Clemson Athletic Director Terry Don Phillips, in more than a “You! Get over here!” moment, looked down the roster of coaches (that included Brad Scott, the former head coach at rival South Carolina) and installed Swinney as interim head coach. Fans thought it a clunker and initially gave Phillips flak for the move — and my, how mistaken they were.

Only six years removed from peddling real estate property, Swinney had found the mountaintop. No, he had never held a coordinator position, but by that time, he was more than ready.

The coach with no name

Dabo Swinney celebrates his second national championship over Alabama. Photo by: Mark Rebilas-USA TODAY Sports

Really, no one saw it coming. Just as no one who played with Dabo could have seen it coming, no one who coached with Dabo could see it coming, no one could have possibly predicted that the coach who virtually no one knew, who had a Power 5 job essentially land in his lap, could have the kind of success he’s had.

Take a look at the numbers: after a 4-3 start, Swinney has won 112 out of his past 139 games. He’s 69-16 in Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) play, with five conference championships — the past four in a row — and two national titles. He’s 2-2 against Nick Saban in College Football Playoff games and 2-1 in games for the national title.

Success? Yes. This kind of success? Truly remarkable.

Not to mention that the cause-and-effect of Clemson’s success has been to create a power vacuum that has eliminated parity in the post-Florida-State, post-Bobby Bowden era of ACC football. Now, with Jimbo Fisher and Mark Richt gone, no serious challenger (will BC, Pitt, or N.C. State please stand up?) has emerged to challenge the purple-and-orange Goliath that is Clemson.

The only question is, “How?” What makes him so special? How, of all people, has Dabo Swinney been able to build one of the top programs in the country?

Isn’t it interesting that Swinney seems less like a football coach than many of his peers and more of a marketing and sales guy, the face and spokesman for a product? And therein lies his brilliance. In today’s modern age of social media, branding, and ballooning athletic departments, the head football coach cannot simply teach Xs and Os and expect to find mega-success. He must CEO the total program. This is proving to be the difference between Swinney and Saban and almost everyone else. Absolutely he has to know football, but the arenas in which Swinney truly excels are sales and recruiting. With passion, optimism, faith, and a bit of folksy wisdom, he’s been able to sell himself and the bliss of Clemson — referred to by many Alabamians as “Auburn with a lake” — to 17- and 18-year-old recruits from all parts the country. He makes Clemson seem almost like Xanadu, Disneyland, a place to which people want to pilgrimage. Call it Camelot, call it Utopia, call it what you want, Swinney has sold this elysian culture located smack dab in a lush patch of northwestern South Carolina. It’s a place that’s all about family, all about love, and all about togetherness.

It’s a place where everyone is All In.

At Clemson, many of his coaches live in the same neighborhood and their kids play summer travel ball on a team called the Orange Crush. Daily, they are encouraged to get out of the office and have lunch with their wives. And because Swinney loves on his assistants and loves on his players, few want to leave. “His staff is happy there, his players are happy there,” Chad Key said. “Once you’re there, Dabo wants to make sure you are happy, you are taken care of.”

It’s like the movie The Firm — only with good intentions.

Stability is another watchword for Swinney’s football program. Since taking over as head football coach in 2008, he has had the luxury of employing only three total offensive coordinators and three total defensive coordinators. After the 2008 season, Swinney replaced OC Vic Koenning with Billy Napier. But Napier was ushered out after the 2010 season and replaced with Chad Morris, now the head coach at Arkansas. Morris apprenticed under Swinney for four years, and in 2015 Tony Elliott and Jeff Scott were installed as co-offensive coordinators. Defensively, Swinney sent Bowden holdover Rob Spence packing before hiring Kevin Steele to man the DC position in 2009. Then, after West Virginia hung 70 on Steele’s defense in the January 2012 Orange Bowl, Swinney canned him and hired current DC Brent Venables, largely regarded as one of the best defensive coordinators in the country and certainly one of the most recognizable and, having just received a raise to $2 million per year, well-paid, too.

Defensive coordinator Brent Venables (purple) has been beside Dabo Swinney during Clemson’s rise. Photo by: Joshua S. Kelly-USA TODAY Sports

Other than those moves, there has been little turbulence at the two most important staff positions. (In contrast, since Saban’s arrival in 2007, Alabama has navigated through seven offensive coordinators — Major Applewhite, Jim McElwain, Doug Nussmeier, Lane Kiffin, Brian Daboll, Mike Locksley, and now Steve Sarkisian — and if you want to count Sarkisian’s infamous one-game replacement of Kiffin before the 2017 Clemson game, eight.)

While staff turnover has become simply the nature of college football, Swinney endures less of it than Saban. Other than the aforementioned Venables, Clemson assistant Danny Pearman has anchored the position of special teams coordinator since 2009, co-OC Jeff Scott has been on staff since 2008, offensive line coach Robbie Caldwell since 2011, and defensive backs coach Michael Reed since 2013.

“It seems to me that the guys Dabo has hired have decided to hang on and raise their kids there and have a family life there,” Sanderson said. “They work for a guy that truly wants you to be a family man. I think we all get caught up in, man, you’ve got to make the next step. But maybe you don’t.”

How this bears out long-term is yet to be determined, and Stallings says he has even encouraged Saban to hire some young coaches that love him and are not looking for another job. “So many of the guys (Saban) hires are older coaches that are looking for a better job. And they get it because they’ve had experience with coach Saban,” Stallings said. “As a result of that, he’s got to replace them every year. I think that was one of coach Bryant’s successes. Everybody that worked for coach Bryant had played for him. We all loved coach Bryant and would do anything for him. Coach Saban has those same qualities, but in my opinion, he needs to hire some of the guys who have played for him.”

Swinney has paired that atmosphere of tranquility with an increased emphasis on recruiting (translated: kicking the thermostat up about 10 notches), and the reason, at least partly, can be traced back to Alabama.

Thad Turnipseed, who played alongside Swinney on the 1992 Alabama national championship team and worked for years as a jack-of-all-trades guru under Saban, was lured to Clemson by guess who and eventually took the position of recruiting director. While at Alabama, Turnipseed saw behind the championship curtain and in turn helped implement many of the Sabanesque ideas at Clemson. According to an article by Dan Wolken in USA Today, “Turnipseed has, in fact, helped Clemson build an Alabama-style operation for recruiting in terms of staffing, analysis of players, structuring visits and social media publicity blasts. Co-offensive coordinator Jeff Scott, who was formerly the recruiting coordinator, said the recruiting-focused staff (including student assistants) has increased from two or three to 40 in recent years.”

With this greater emphasis on recruiting, Clemson has seen a major uptick in this area over the past six years. Between 2014 and 2015, Clemson jumped from 13th in recruiting to 4. It has garnered a top 10 recruiting class in five of the past six seasons and currently stands at No. 1 for the 2020 class.

Understanding that players love facilities and conveniences, Turnipseed oversaw a $55 million upgrade that included the addition of a bowling alley and slide. Turnipseed has become an indispensable part of the program, arguably the missing cog between 10-4 and 15-0.

Next, in a volatile profession, Swinney looks like he’s having fun. He celebrates by throwing pizza parties. He’s the antithesis of the Old School variety of coaches, the growling, scowling, bitter-faced field tyrants who failed to have a ball while working and were taciturn in their relationship with their players. Conversely, Dabo has a personality you can catch. Even his name — Dabo — evokes a softer edge, an arm-around-shoulder father figure motif (ask yourself: would he have the same success if his name was Jim Smith?).

Lastly, Swinney has taken the Stallings/Alabama model and put gullwing doors on it. He has combined the experiences he had as a student under Stallings, Dubose, Wingo and Bowden and tweaked it to his comfort level. Most successful coaches can be traced back to another successful coach, and Swinney bears the bright fruit of the Stallings/Tom Landry/Bear Bryant tree.

Quite modestly, Stallings disavows any influence he had on Swinney — “I don’t think I contributed to his success” — except that he acknowledges he gave him a job, which “helped him along.” The two coaches talk often, but Stallings says that Dabo doesn’t call to ask for advice. “He really doesn’t need a lot of assistance and help from me. … He’s won national championships … what does he want advice from an old coach? When we visit, most of the time it’s just checking on you to make sure you are OK,” Stallings said.

In reality, Stallings’ influence has been pronounced, so much so that Swinney invites Stallings to speak words of wisdom to his team. Last fall before Clemson played Duke, Stallings attended a coaches meeting while he was in town to watch his grandson, J.C. Chalk, play. According to Key, Stallings sat just behind Swinney at the head of the table, like an advisor or consigliere.

Key tells the story: “So Dabo had lined out a 15, 20 minute staff meeting. He got started and about five minutes in, he was going over something and all of a sudden he sees this hand just kind of reach over and land on the table. It was Coach Stallings and he was like, ‘Hey, excuse me, I just wanted to interrupt and I just wanted to add this. Back when I was at such and such. …’ Dabo just kind of sat back and listened to Coach Stallings say his piece. Well, he got back to his meeting again and was talking about some other things he wanted to cover and here comes that hand again. Coach Stallings lays it on the table again. ‘Excuse me, Dabo, I just wanted to add this as well.’ What planned to be a 15 or 20 minute staff meeting turned into a 45 or 50 minute staff meeting.”

There’s an old saying, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” and sometimes the teacher doesn’t realize how much the pupil is taking in. Sanderson remembers that Swinney “really paid attention to all the details of how Coach Stallings ran his program. He wrote them down and put them in his book.” Key adds that as an assistant under Stallings, Swinney was “always a great note taker” while Diehl claims his learning capacity at the wide receiver position was “like a sponge.”

“(Coach Stallings) has made a tremendous impact on Dabo,” Key added. “Things are eerily, eerily similar to the way that we did things when Stallings was in Tuscaloosa, even down to Friday walkthroughs. A lot of his practice scheduling, offseason workouts, a lot of things are very, very similar.”

In Stallings, Swinney saw the importance of a leader encircling himself with talented individuals who possessed integrity. Swinney has taken that to heart and has decided to fill the seats at his coaching table with like individuals. “I think, first off all, he hires good people and he recruits good people,” Stallings told SDS. “You don’t read about the Clemson players out drinking and carousing at night. They can be a good player and not have good character and I don’t think Dabo would take them. So I think Dabo’s players have good character and I think his coaches have good character.”

It’s no surprise, then, that many of Swinney’s staffers are folks whom Stallings already selected. For instance, coach Woody McCorvey, who is Clemson’s Assistant AD of Football Administration, was Swinney’s position coach at Alabama. Pearman, who coaches special teams and tight ends, was the special teams coordinator on Stallings’ 1992 championship team. Mickey Conn, a Clemson assistant in charge of safeties, played for Stallings at Alabama from 1992-94. Lemanski Hall, Swinney’s defensive ends coach, was a major part of Alabama’s menacing defense in 1992, actually leading the team in tackles with bruisers like Curry, Copeland, Langham and Teague in the mix. Paul Hogan, Football Senior Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach at Clemson, was recruited by Stallings and played center from 1997-2000. Other Clemson staffers or previous staffers with Alabama ties include Todd Bates, assistant coach in charge of defensive tackles, the aforementioned Kevin Steele and Charlie Harbison, who was also a wide receivers coach at Alabama from 1998-2000.

Swinney has also proved to be an intense loyalist. In addition to Stallings’ grandson, Swinney has also given several sons of his college teammates and friends an opportunity to play Division I football. Nolan Turner, who is the son of the late ‘Bama great Kevin Turner, is on the Tigers’ roster, as is Carson Donnelly, son of Chris Donnelly, former Crimson Tide receiver, and Hall Morton, son of Alex Morton, Swinney’s roommate at Alabama. (In addition, you might notice that he has made room on the roster for his own sons, as well as the sons of Venables and Kirk Herbstreit.)

While others might take a businesslike approach, Swinney uses Hallmark-Channel-like ideals as the foundation for his program. But it doesn’t come across fake or disingenuous. He truly cares for the people around him. He rewards them, too. Clemson’s coaching staff is set to make more than $15 million this season.

Perhaps he is intent on creating the life of harmony he never got to experience growing up.

A final thought

Dabo Swinney brought so much of Alabama’s winning culture with him to Clemson, it’s fair to wonder would he ever want or need to go back? Photo by: Kent Gidley/Crimson Tide Sports

One of the most conversational aspects of Swinney’s aura, particularly in Bible Belt, America, is his outspoken faith. In contrast to many Christian coaches who choose to keep their faith private, Swinney wears it as his proudest badge. He’s used the podium as a pulpit, in some instances to comment on controversial topics. But he doesn’t come off as though he’s operating out of some sense of inflated self-importance. As a result, he’s made plenty of fans who don’t necessarily give a hoot about rooting for “Climpson” otherwise. His ‘Bama teammates ratify that it isn’t just a show; it’s been something that’s a part of his life for as far back as they can remember. “He’s never shied away from his faith. I think it’s absolutely phenomenal that he doesn’t, even on a bigger platform,” Bryne Diehl said. “And he lives it, too. He’s always been that way. He’s not some flash in the pan, ‘well he’s doing this because he’s Dabo.’ It’s not that way at all — trust me.”

The consensus among Swinney’s teammates at Alabama is that he is a good guy now, and he was a good guy then. “I can tell you, I don’t recall any negative stories about Dabo at all,” Sanderson said. “I’ve known Dabo a long time, and he’s always had his life together. If he didn’t have it together he just really did a great job of not letting anybody know about it. But I really think he just always lived what he preached and really believed, truly believed, genuinely, what he talks about.”

Diehl and Key agree. “Looking back on it, he was mature beyond his years,” Diehl added. “You never heard that Dabo did anything stupid. He always went to class. Never missed a meeting. Always did what he was supposed to do. If coaches asked him to do something, he’d do it. That trickled down, even when he was a G.A. Some other people, they may have to prod a little bit. He’s one of those type guys that got it.”

Like Stallings, Swinney is modest, too. “He always likes to talk about Little Ol’ Clemson,” Key said. “That’s going to be a harder sell because it’s not Little Ol’ Clemson now. Whenever you build a program and a culture like he has, people want to become a part of that.”

So what’s the future for Clemson and Dabo Swinney? Can the Tigers establish success over the long haul, or will Clemson default back to the Clemson of the first 117 years? Can Clemson join blue bloods like Alabama, Notre Dame, Ohio State and USC in the pantheon of college football? It’s quite possible, if this 5-year trend continues.

The more pressing question — and certainly one that is posited daily in Alabama, is, “Will Dabo eventually come back home to be the head coach of the Crimson Tide?” For whatever reason, that homecoming seems less likely with every year that passes. Familiar faces from Alabama, fat contracts, the capturing of more rings, and the building of the Tuscaloosa East in Clemson might ultimately be the dissuading factors.

But a favorite son never knows how he’ll respond until Mama rings that bell.

Remember how membership in the Alabama fraternity has its privileges? There are also Alabama problems. Many of Dabo’s former teammates at Alabama find themselves a bit torn whenever Clemson meets Alabama for the national title. They don’t want their buddy to lose, but ‘Bama blood runs deep. Diehl, who talks to coach Stallings often, recalls a phone conversation he was having with his old coach before last year’s championship game. “I said, ‘well coach, look at it this way.’ I said, ‘you know I’m pulling for Alabama but we are kind of in a no-lose situation.’ He busted out laughing. He said, ‘you know you’re right. Ain’t many folks going to be in a situation like that.’”

A few years ago, Alabama had a football reunion where Diehl, salesman for Graybar Electric in Birmingham, ran into Swinney. While the two men were catching up on lost time, Swinney asked, “What are you doing now?”

“I’m going to be your special teams coordinator,” Diehl replied jokingly. “You just don’t know it yet.”

Al Blanton is the owner of Blanton Media Group based out of Jasper, Ala.