'We changed the game:' Hal Mumme, Mike Leach and the makings of the most innovative friendship in college football

Mike Leach was late. Of course, he was late. He was always late.

Hal Mumme – Leach’s boss and his head coach, his innovator-in-charge and his comrade in creativity, and most importantly, his future friend for nearly four decades – had tasked him with finding some talent down in Florida, so, obviously, Leach found a kicker in Key West.

This was 1989, and they were up in Iowa, coaching at tiny Iowa Wesleyan College of the NAIA, tucked into a basement office, working on a beyond-meager budget, on their way to changing football forever. Now, after a couple winning of seasons, they were flush with resources. They somehow wrangled $800 for roundtrip flights from Chicago to Orlando. At this point, Leach had been working with Mumme for a few years, and Mumme had to depend on him and trust his judgment.

Except for his tardiness. Leach was always late, and this time, it mattered. They had an 8 a.m. flight out of Midway Airport, which meant they had to leave Mount Pleasant, Iowa, at 2 a.m. The airfare was not refundable.

“I said, ‘Mike, look, if we miss this flight, they’re gonna fire me, and I’m gonna fire you,’” Mumme said.

Mumme is up and ready by 1, has some coffee and waits. It’s 5 ‘til 2, no Mike. Now it’s 5 after 2, no Mike. Mumme’s antennae go up.

“I think, ‘I’d better call him,’ and on the other end of the line there was this disheveled speech, and I just knew it – I had woken him up,” Mumme said. “I say, you’ve got 10 minutes to get here or you’re fired,’ and he gets there in 10 minutes, his suitcase stuffed with clothes hanging out, in this go-kart ready to drive us, and I’m so mad at him.”

How mad?

“We drive for 4 hours and he’s doing his best imitation of Dale Earnhardt, and I have not spoken to him for 4 hours,” he said. “We go to the gate, sit there, and I still don’t speak to him. We finally get on the plane — now we’ve been together for 5 hours — and I have not spoken a word. We sit down on the airplane, put on our seat belts, and I still haven’t spoken to him. And you can picture Mike doing this — he had this way of dead-panning things — so we’re sitting there, and he finally looks at me and says, ‘Apparently you’re mad at me.’”

Mumme couldn’t help but crack up. For the next three-plus decades, sportswriters and coaches and fans alike would come to hear that sardonic voice in their minds.

Mumme and Leach made it to the Sunshine State, but they did a lot more than find themselves a kicker.

What they found in Florida would change the course of their lives, and the course of college football history. It would also solidify a friendship that lasted until Leach’s untimely death this week at the age of 61. A friendship that in some ways will last forever.

* * * * *

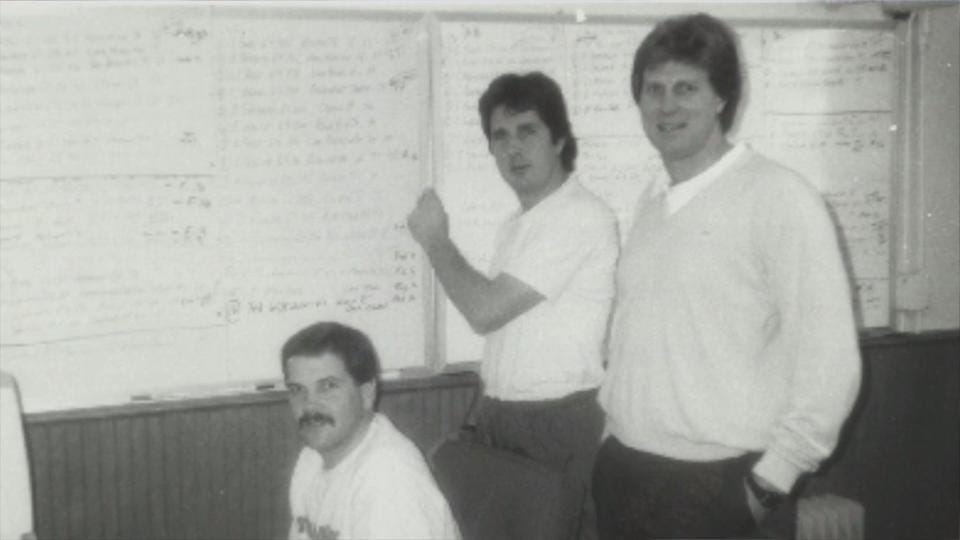

Hal Mumme, far right, and Mike Leach started their pioneering Air Raid offense at Iowa Wesleyan, where they set records, won 10 games in 1991 and reached the NAIA playoffs for the first time. — Photo courtesy of Iowa Wesleyan

It all started with a fateful phone call.

Mumme was head coach at Copperas Cove High School in Texas when his friend, Steve Kazor, gave him a call. Kazor, the long-time Special Teams Coordinator for the Chicago Bears, was close friends with the president of Iowa Wesleyan College, which had a head coach opening for its NAIA football program. Kazor was the one-man search committee, and he knew what Mumme was doing down in Texas – incorporating BYU’s innovative spread offense, scheming abundant quick passes and shutting down Texas high schools’ stodgy I-formation offenses on the regular – and asked him if he wanted to try out his offense at the college level.

This wasn’t a plum gig. The Tigers hadn’t won a game in two years and only had two players who came back for spring football.

Mumme brought his Copperas Cove defensive coordinator along with him, and he intended to act as his own offensive coordinator, but he needed an offensive line coach.

“I tried to talk to several, and when I told them what I wanted to do – big line splits, 2-point stances, throw the ball 50 times a game – most of them were not interested in it,” Mumme said. “In fact, a lot of them were pretty rude about it.” But Mumme wasn’t about to stop there. “I said, ‘I’m gonna look for the smartest guy I can find and teach him what I want.”

It didn’t go well.

“In those days, you’d get these pink slips for incoming phone calls, and usually those were all coaches who wanted to work for you,” Mumme said. “Mine were all athletic directors who wanted us to be their homecoming game. The only two resumes I got were from Mike and from some guy in L.A., who offered to bring some of his local gang with him.”

Leach had been a rugby player at BYU but stopped playing football in high school after suffering a career-ending injury. But he had a front-row seat for the LaVell Edwards and the Cougars high-powered passing offense, which served as the precursor to the Air Raid. BYU went a combined 42-8 in Leach’s four years as a student.

In 2009 Mike Leach, former @byurugby player & TT HC at the time, flew out to Stanford to watch the @byurugby national title game vs Cal.

The night before the game he went to an alumni/team gathering & was chatting with everyone there.

The next night BYU won its first natty.

— Jarom Jordan (@jaromjordan) December 13, 2022

In 1979, he watched quarterback Marc Wilson set nine NCAA records and become the first Cougar to earn consensus first-team All-American honors. A year later as a sophomore, he watched as Jim McMahon set 32 NCAA records, including single-season records for passing yards (4,571), touchdown passes (47), passing efficiency (176.9) and total offense (4,627). A year after that, McMahon passed for 3,555 yards and 30 touchdowns in the regular season, again led BYU to a WAC championship and was named First-team All-American by five different organizations while finishing third in Heisman Trophy voting. As a senior, Leach watched Steve Young inherit the position and continue the Cougars’ success, passing for nearly 4,000 yards and 33 touchdowns, with an NCAA-record 71.3% completion percentage as BYU set another NCAA record averaging 584.2 yards per game of total offense.

All along the way, Leach studied what made the Cougars click, even sitting in on practices with assistant coaches Norm Chow and Roger French. He became a devout disciple of Edwards’ evolutionary ways and of French’s offensive line techniques and spacing.

“(Edwards) is easily one of the greatest coaches that ever coached. I think that’s indisputable. I know him a little. I’d like to know him a lot better,” Leach told the Deseret News in 2012. “He’s a guy that never overreacted, didn’t panic. … He trusted good people to do things. In the end, it was a product, an environment, of trust and focus. It’s a foundation that still survives at BYU to an extent. Football-wise, it’s very hard to imagine what BYU would be like without LaVell Edwards and also football in America what it would be like without LaVell Edwards. I’m not the only person that LaVell Edwards influenced on throwing the football.”

With a brilliant mind for law, Leach decided to attend Pepperdine Law School, but at some point realized he did not want to become a lawyer and instead chose to get a Masters degree at the United States Sports Academy in Daphne, Ala. When he first inquired with Mumme, Leach had only been coaching two years, first as a volunteer assistant at Cal Poly and then as an assistant for tiny College of the Desert in Palm Springs, Calif., for a whopping $6,000 salary.

It wasn’t exactly a glowing resume, but it did have one important note.

“Mike’s resume had BYU on the top of it, which piqued my interest,” Mumme said. “That started a 2-month conversation with him and in March, after two months of sharing ideas on how to implement this offense, I said, ‘Why don’t you meet me at BYU, I go there every year to study.’”

It was there that the friendship first formed, and Mumme knew he’d found his match. He knew he wanted to hire Leach as his offensive line coach and key architect of the blocking schemes that would make the passing game flourish. But there were some formalities first.

A small school with a small department, Leach had to go through the car wash: Athletic director, financial aid director, everyone. Let’s just say, they were not impressed. But part of Mumme’s deal when he was hired: Absolute autonomy over the makeup of the staff

“The great thing about Mike is I never had to worry about being the worst-dressed guy in the room, and I’m not the best dresser myself,” he said. “He had some wrinkled khakis, and a wrinkled shirt – not what everyone was expecting to see. The AD comes into my office at the end of the day, and I said how’d it go? ‘They don’t like him.’ I say, ‘Who?’ ‘No one likes him. They don’t think he’s a football coach.’”

“I said, ‘F— you, I get to hire whoever I want.’”

* * * * *

Mumme quickly learned he’d made the right decision. Leach was late — of course — to join the Tigers’ team after spending the summer of 1987 as head coach of the Pori Bears of the American Football Association of Finland, and on the first day of Leach’s arrival, Mumme went up to the offensive line meeting room when Leach was meeting with his new offensive line.

“It was obvious he owned the room,” Mumme said. “He’d have no trouble implementing what I wanted.”

That first year, with a patchwork team assembled in haste, Iowa Wesleyan won 7 games. The next year, 8 games, and going into Year 3, Mumme said, “I wasn’t getting calls to play in anyone’s homecoming anymore.”

No one would play the Tigers anymore, really. They were forced to play up – Division II and now-FCS squads – to the point that Mumme told Leach they had the best team yet but wouldn’t win 3 games. Mumme told Leach, “We need to find our edge.”

But first, they’d need to find some talent.

They had some free time in Florida, as well, and Mumme knew a coach on the Orlando Thunder of the World League, so they headed to practice, where Mumme asked Don Mathews – the head coach of the Thunder and a legendary Canadian Football League 5-time Grey Cup winner – to see the best drill they had. Mathews said, “Wait ‘til you see our 2-minute offense.”

“Look, we’d seen 2-minute offenses before, but you’d never seen it happen like this,” Mumme said. “The offense was on one sideline doing their subbing, the defense on the other, it was the most efficient 2-minute offense I’d ever seen. I looked at Mike, and I said, ‘I think we found our edge. We’re going to do it all the time.’”

The Thunder coaches showed the two Tiger coaches how to practice a full-time, no-huddle, sped-up offense. Mumme and Leach went back to Mount Pleasant and installed the fastest offense in football. But Iowa Wesleyan didn’t win 3 games that year. The Tigers won 10 in 1991 and advanced to the playoffs for the first time in the 100-year history of the school.

* * * * *

From there, the Air Raid took flight.

In 1992, Mumme and Leach were hired by Valdosta State, where they brought modern football to the South, bucking decades of between-the-tackle tradition. It wasn’t exactly received well.

Who were these corn-fed kooks with their crazy offense and their weird schemes? Local newspapers provided a mix of intrigue and skepticism but Mumme and Leach were undeterred. Mumme knew the passion for the game in Georgia and figured they should hold a coaching clinic. He brought in two NFL coaches, BYU coaches, state championship coaches, all organized in a 2-day event.

Zero people showed up. Not a single high school coach in Georgia showed up.

“You almost have to try to do that,” Mumme said. “We just sat around and clinic-ed each other for 2 days.”

Mumme called it a “backlash” to the hype, this idea that you could take a gimmick offense from an NAIA in Iowa down to the big dogs of Georgia football. Georgians played football a certain type of way, and it wasn’t short passes and funky route trees.

“At that time, the idea of Georgia changing its offense was a toss sweep to the left,” Mumme said.

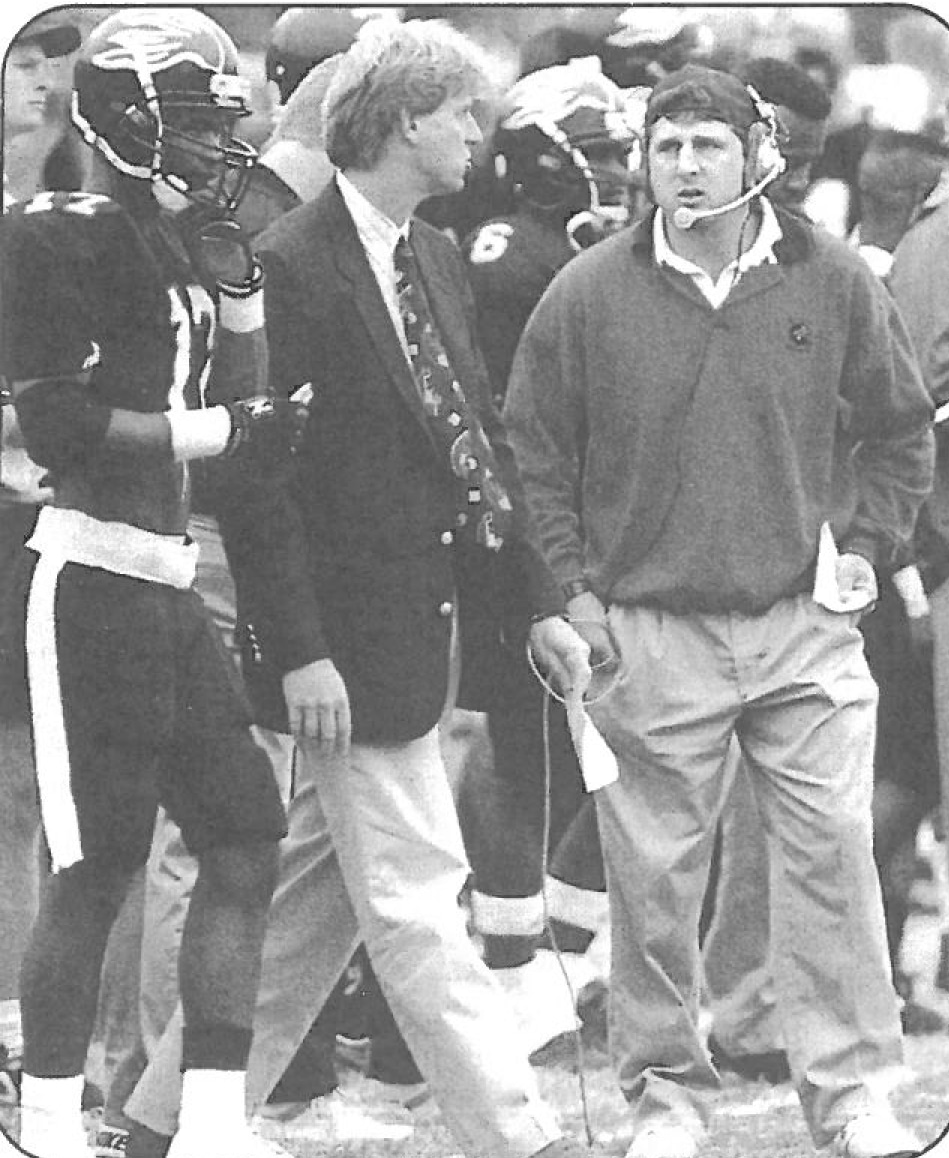

Hal Mumme and Mike Leach had to win over naysayers after taking their Air Raid to Valdosta State. — Photo courtesy of Valdosta State

It did not take long to quiet the naysayers. In Year 3, the Blazers went 11-2 and advanced to the NCAA Div. II quarterfinals. Two years later, they won 10 games and their first Gulf South Conference championship.

Teams across the country started to notice, and Mumme got a call from Kentucky athletic director C.M. Newton. The Wildcats had a talented young rising sophomore named Tim Couch who had set several national passing records in high school. Mumme was intrigued. This was their chance to really prove their system worked.

It worked.

The offense, at least. In 1997, Mumme and Leach’s first season at the helm, Couch had 3,884 passing yards and 37 passing touchdowns, demolishing Kentucky’s passing records. The Wildcats even beat Alabama for the first time in 75 years. They haven’t beaten the Tide since. The next year, Couch was even better, setting numerous passing records and shattering the SEC record for passing yards as Kentucky won 7 games for just for 4th time in 4 decades.

And then Mumme got another phone call. Bob Stoops, who was defensive coordinator for Steve Spurrier at Florida, had just gotten hired by Oklahoma and called to inquire about Leach.

“I said, ‘Do you want to hire Mike because it’s sexy to hire a Kentucky coach? Or do you want to hire Mike?” Mumme said. “He went on to quote the stats of our last two games. He wanted to run our offense, and that was OK because we weren’t in the same conference, so credit to Bob – he was the first guy to run the Air Raid who wasn’t on my staff.”

Still, it was a tough conversation.

“Mike came into my office one day and he said, ‘I’m the AVIS rental car of assistant coaches,’” Mumme said. “He wanted to be a head coach really bad, and I wanted to see him become a head coach. I told him, ‘I hate to lose you, but I think this would be a good move. Bob’s a defensive guy, you’ll get all the credit for his offense.’”

The Sooners hadn’t won anything since the Barry Switzer days, but Bob Stoops would change that in a hurry. With Leach as his offensive coordinator, Stoops led Oklahoma to a 7-5 record. The offense averaged 35.7 points per game, finishing No. 6 in the country in scoring a year after averaging 16.7 points and finishing 101st.

Texas Tech was sold. Leach was given his first head coaching gig since his Finnish finish 13 years before. He’d go on to one of the most improbably coaching careers in college football history, leading Texas Tech, Washington State and Mississippi State up from the depths.

And in addition to popularizing the Air Raid passing offense — which he named, by the way — he revolutionized the way teams looked at offense in the first place.

* * * * *

When Mumme hired Leach at Iowa Wesleyan, he made it clear he couldn’t pay Leach much, and he emphasized he’d have to work multiple positions. In addition to offensive line coach, the 26-year old Leach served as video coordinator, equipment manager, taught 2 business law classes and was the sports information director for the team. All for $12,000 a year.

One day, Leach went up to Mumme and said all these sportswriters were asking about the name of the offense. Mumme said you have at it.

The buffest of history buffs, Leach called it the Air Raid, with an assist from a local fan.

“I’m credited with the title Air Raid,” told reporters before his return to Kentucky as Mississippi State head coach in 2020. “When we were at Iowa Wesleyan College, some guy brought in this air raid siren, and it was fun at the time to name offenses — West Coast offense, Fun-‘N’-Gun, Run-and-Shoot. So this guy, Bob Lamb, comes in with an air raid siren … and says look what I’ve got, and he turns this thing on, loud as it can be because its echoing off all the walls (Leach mimics a siren sound) and he’s just letting it rip. We take it out there, and our games would have 1,000, maybe 3,000 on a really big crowd, playing on a high school field, and Bob would stand out there in the end zone and he would turn that thing on when we’d score.

“Then after a while, he and his friends had so much fun with it, they’d just blast it for anything, just randomly, whenever they felt like it. Even when the other quarterback was trying to call plays because we didn’t have a lot of crowd noise there. He’d get kicked out of games and stuff and had to go stand on the edge of the fence in the back. It was greatness.

“From there, they started calling it the Air Raid. I’m kind of credited with the idea of calling it the Air Raid.”

He’s credited for a lot more than that.

Mike Leach's coaching legacy lives on ? pic.twitter.com/O4PZTp52lH

— FOX College Football (@CFBONFOX) December 13, 2022

But on one point, Mumme is clear: They may have popularized a new way of moving the ball down the field, but they did not invent anything. They stole BYU’s offensive line splits and passing concepts and Mathews’ no-huddle offense and Spurrier’s up-tempo pace. They stole all the way back to Pop Warner.

“We’re kind of like Nabisco,” Mumme said with a laugh. “They didn’t invent cookies, but they did package Oreos.”

To popularize it, Mumme reasoned, they’d have to package it. For their concepts to take root in the game, to really change things, they’d have to be able to teach the Air Raid.

Only one problem. They didn’t have a playbook.

* * * * *

Well, once they had a playbook.

When they went to Valdosta State, Mumme hired former long-time NFL offensive lineman Guy Morriss as offensive line coach, allowing Leach to slide over to quarterbacks and receivers and giving him a chance to add to his overall coaching acumen.

“We didn’t have a playbook, and Guy says, ‘You don’t have a playbook? We gotta have a playbook,’ and during spring break, Guy has his forms out and he’s drawing diagrams, putting all this stuff down and about halfway through spring break, Mike and I just said, ‘Screw it, we’re going to the beach; Guy, if you wanna finish it go ahead.’ He finishes it — that was 1992 – and flash forward to 1999, and the only Air Raid playbook ever has been on the credenza behind his desk. We had one copy, I don’t think we ever opened it.”

When Leach was hired by Oklahoma, he called Mumme in a panic. They were getting ready for spring practice and Stoops said he needed an offensive playbook on his desk by Monday morning. Mumme suggested Leach call Morriss, so he did, and Morriss dug it out. Leach made some copies, gave one to Stoops, but, Mumme said, never opened it himself.

They Sooners made it through the season, the offense shined and Leach got poached by Texas Tech.

So Stoops called Mumme again.

“‘I want to keep the offense, but (new offensive coordinator) Mark Mangino needs to know how to call it,'” Mumme said. “He couldn’t say this to Mike because they’d play each other.”

Stoops asked Mumme if he could send Mangino over to Kentucky to learn as much as he could.

“Mangino came over for a week, and I tried to get him as up to speed as I could. At the end of the week, I said do you have any questions, and Mangino says just one – ‘When we got there, Mike gave us these playbooks and there’s a lot we never even used, and Mike never even talked about.’ I told Bob the story, and he just started laughing. Flash forward to 2020. Stoops calls me and says come be the offensive coordinator for the Dallas Renegades (of the XFL), I go over there, and Bob and I are talking one night, and I say Bob, ‘Did you ever hear the playbook story?’ ‘No, what are you talking about?’ He was just floored.”

Mumme wraps up one of the great stories on The Pirate.

“But we always said the Air Raid was a philosophy,” he said, “not a playbook.”

* * * * *

Their record was 15 hours.

“He had way of casting a spell over you,” Mumme said by phone on Tuesday, still reeling from the loss of his long-time friend. “You just wanted to listen to him. My personal best was 15 hours on the phone with him. On a bus from Jackson, Miss., to Williamsburg, Ky., for a game in 2014. We had to leave on a Thursday night and sleep on the bus, and I’ve got my pillows and my bedding and my Ambien, and I’m ready to sack out. We leave the city limits, the phone rings and it’s Mike. When I hung up, we were almost in Kentucky. We’d talked about everything that was not football.”

Mumme sounds wistful.

“We used to sit around Iowa and delight in being nonconformists,” he continues. “We were wacky and crazy. We enjoyed thumbing our nose at the authorities in the game, and Mike was the nose-thumber in charge. He was notorious for long phone conversations. That changed in the last few years. But he’d still call you, and you never minded it because it was always so interesting. He just had this way about him.”

They forged a friendship over football, but they bonded over Jimmy Buffett and the Battle of Little Big Horn. For Mumme it was simple: “He loved historical stories, and that’s why we hit it off.” They’d get in the car and just go, go, go. They’d argue over In-n-Out versus Whataburger.

“A lot of what you’d see in a minute soundbite, I got the dissertation version,” Mumme said.

Iowa Wesleyan had given him a 1984 Ford Taurus to recruit in, and if someone was throwing the football, “we’d go there and drive there. We drove to Green Bay. We ended up in Miami picking Dennis Erickson’s brain about the long pass. It was just a time of trying to learn and increase our knowledge, and there were a couple ways to pass the time. We both loved Jimmy Buffett music, and I’d put in the tape, and Mike would discuss the meaning of the lyrics. We’d listen to an entire album and he’d say you know what ‘A Pirate Looks at 40’ is about, and he’d expand on it for hours. It was incredibly fascinating and incredibly fun and we became very close. You never had to worry about there being a lull. You’d just have to give him a topic.”

It went on like this for 11 years, through three schools and thousands of yards and just as many miles. As football coaches go, they were simpatico. As cohesive as they were creative. A pair of brilliant offensive minds who were just plain brilliant.

“The thing about both of us that we really enjoyed is neither of us were afraid to work without a net,” Mumme said. “A lot of coaches, they want the safe play. We didn’t care about being fired. We didn’t care about where we coached as long as we could do what we wanted to do. And we changed the game. You can’t separate the two of us. It was really a collaboration. Like McCartney and Lennon.”

* * * * *

As we talk, Mumme’s wife, June, overhears the conversation.

Mumme is talking about those long car rides and those long conversations, and June shouts out loud, loud enough to hear in the background.

“Yin and Yang,” she says.

Mumme laughs and sighs.

“Yin and Yang, she said.”

Cover photo of Hal Mumme and Mike Leach courtesy of the University of Kentucky athletics.