Why episodes 3 and 4 of 'The Last Dance' reminded me of a certain SEC storyline in 2019

“It seems that in sports, there’s always that one team that you have to overcome, and you almost build your team to beat them …”

Andrea Kremer said it best in Sunday night’s airing of “The Last Dance.” In case you missed episodes 3 and 4 of the highly-anticipated documentary on the 1990s Chicago Bulls, that sentence was the most noteworthy line of the night.

(Well, besides Horace Grant describing the Bad Boys Detroit Pistons as “straight up b—-es.”)

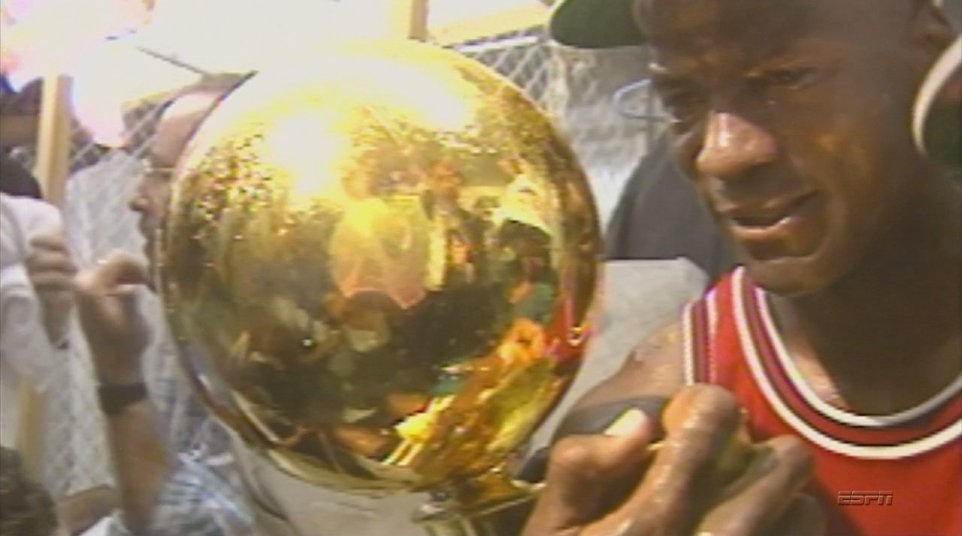

What the Bulls went through from 1988-90 — they lost 3 consecutive years to the Pistons in the playoffs — set the stage for the dynasty that followed. At the time, Detroit was the proverbial hurdle that the Bulls couldn’t overcome. They pushed Michael Jordan around and took him out of his comfort zone. “The Jordan Rules” were the formula that even His Airness couldn’t crack on his own.

How did the Pistons stop MJ?

The Jordan Rules. #TheLastDance pic.twitter.com/G8UchQU260

— ESPN (@espn) April 27, 2020

So, as the great teams do, the Bulls built their team to beat the Pistons after the Game 7 loss in the 1990 Eastern Conference Finals … and it worked.

Does that sound like anyone else you know?

I couldn’t help but think of LSU’s seemingly repeated failed attempts to beat Alabama in the 2010s. That is, until LSU built its team to finally overcome the Crimson Tide in 2019.

Rooted at the Bulls’ ability to finally take down the Pistons and LSU’s ability to finally take down Alabama was 1 thing — a willingness to adjust. Bulls guard B.J. Armstrong said in the doc, “we had to change something about ourselves or we weren’t gonna beat them.” It’s easy to take that awareness for granted.

It might seem obvious that Jordan and the Bulls went into the offseason after the 1990 loss to the Pistons and hit the weights. Of course they needed to get stronger in order to not get pushed off the court. But for Jordan, that was the first time he’d really lifted.

It might seem obvious that Joe Burrow and the Tigers went into the offseason after getting shut out by Alabama in 2018 and switched to the spread offense. Of course they needed to get more diverse and not continue running into a brick wall. But for LSU, that was the first time they really had the personnel to run that system successfully.

Ah, speaking of the personnel adjustments, there’s another similarity I picked up on. Doug Collins is Les Miles in this story.

Collins took the Bulls to the Eastern Conference Finals in 1988-89. Collins’ offensive philosophy was all about getting the ball in Jordan’s hands and letting him take over. But as “The Last Dance” outlined, catering to Jordan wasn’t quite getting the Bulls to where they wanted to go. In 1989, Bulls general manager Jerry Krause made the difficult decision to fire Collins and promote assistant Phil Jackson to head coach.

As for Miles, he won a title and led LSU to finishes in the top 20 in 9 of 11 seasons. His offensive philosophy was about the power running game, double-tight end sets and fullbacks. But it was clear in 2016 that he no longer had the ability to take LSU where it wanted to go. That season, athletic director Joe Alleva made the difficult decision to fire Miles and promote assistant Ed Orgeron to head coach.

Just like it wasn’t enough for the Bulls in 1990 to just have Jackson coaching Jordan, it wasn’t enough for LSU in 2018 to just have Orgeron coaching Burrow. That one last adjustment was needed.

Both teams, ironically enough, had to learn how to spread the ball around. The Bulls embraced assistant Tex Winter’s triangle offense once Jackson took over, and the Tigers embraced Joe Brady’s version of the spread offense after Orgeron hired him. No longer could Detroit shut down Chicago by selling out to stop Jordan — and no longer could Alabama shut down LSU by selling out to stop the ground game (Alabama actually didn’t have to “sell out” to stop the run because it could handle the Tigers at the line of scrimmage but just stick with me).

Simple enough, right?

So why did it take Chicago 3 years of Detroit losses and LSU 7 seasons of Alabama losses to finally adjust? Personnel. It takes a perfect formula to yield a champion.

The combination of Jackson’s presence and Winter’s offense allowed for a stronger Jordan to make everyone better. The combination of Orgeron’s presence and Brady’s offense allowed for a more confident Burrow to become the best version of himself. Jordan learned how to rely on Grant and Scottie Pippen, and Burrow learned how to maximize the abilities of Ja’Marr Chase and Justin Jefferson.

We all knew that Orgeron’s LSU tenure wasn’t going to be defined by 10-win seasons. It was going to be defined by whether he’d overcome the Alabama hurdle. It fueled his post-2018 spring decision to get Burrow, and it absolutely fueled his post-2018 season decision to hire Brady.

The same could be said for how people talked about Jordan. Even though he was a league MVP and undoubtedly the best player on the planet, his legacy wasn’t going to be defined by scoring titles. Once upon a time, we didn’t know if Jordan could make his teammates better. But he was willing to adjust. Jordan embraced the idea of hitting John Paxson for a corner-3 instead of attacking the basket 2-on-1. What that started was arguably the most impressive decade of professional sports of the past 40 years.

We don’t know what’s next for LSU. The difference is obviously unlike the Bulls, who had Jordan and Pippen for more than a decade, the Tigers just lost a record 14 players to the NFL Draft. Unlike the Pistons, Alabama didn’t head to the locker room with 8 seconds left with some unwillingness to pass the torch . For all we know, Alabama will take the torch back next year.

Maybe it’s Georgia and the new Air Raid offense that’ll allow the program to finally get over the Alabama/LSU hump. Well, that and the 1980 hump.

What seems likely is that somewhere, in the midst of this time without sports, a team is convinced that it made the right adjustment needed to take down their version of the Bad Boys Pistons or Alabama.

Dynasties gotta start somewhere — and often, their base ingredient is years of punishment courtesy of the same neighborhood bully.