Film Study: Trevor Knight has to be at dual-threat best to beat Alabama

Film Study: Trevor Knight has to be at dual-threat best to beat Alabama

A weekly look inside an SEC playbook.

If Alabama fans remember anything about Trevor Knight, it’s that the kid can throw. The last time they saw him up close, in the 2014 Sugar Bowl, Knight — then an unheralded, injury-prone redshirt freshman wrapping up his first season as a starter at Oklahoma — was turning in the game of his life, bombing the Crimson Tide for career highs in passing yards (348) and touchdowns (4) in a 45-31 stunner.

Alabama had never given up that many points in a game under Nick Saban, and hasn’t again since. Overnight, the Sooners vaulted onto the short list of serious national contenders entering the 2014 season, and Knight was feted as one of the game’s ascendant young passers.

And if that’s where the memory ends, then the quarterback who shows up in Tuscaloosa this weekend for a Top-10 collision between Bama and Texas A&M will be barely recognizable. Not only will Knight be wearing a different uniform, in many ways he’s an entirely different player than he was three years ago, both more mature after ending his Oklahoma career on the bench and more secure in an offense that’s proven ideally suited to his talents.

Specifically (and perhaps surprisingly, given A&M’s high-flying bona fides), coach Kevin Sumlin and first-year offensive coordinator Noel Mazzone have tapped primarily into Knight’s mobility, building a system that revolves around his capacity to serve as a de facto tailback in the running games as much as it does his ability to challenge opposing secondaries with his arm.

So far, so good on both counts. Through six games, Knight is the point man for an attack that averages 40 points per game, leads the SEC in total offense, and has improved its rushing average by more than 100 yards game over its mediocre output on the ground in 2014 and ’15.

At midseason, A&M is one of only three offenses nationally (along with Louisville and Baylor) averaging 250 yards per game rushing (274.3) and passing (258.5); it’s the only team that has eclipsed 200 yards by land and air in every game. Individually, the Aggies boast the SEC’s leading rusher, true freshman Trayveon Williams, and its second-leading receiver, senior Josh Reynolds.

Most important, they boast an undefeated record, which belongs as much to Knight as to anyone, and puts them in position on Saturday for a genuine breakthrough against the Crimson juggernaut. A&M needed a fresh start at quarterback this season as much as Knight needed a fresh start of his own, and halfway home the marriage of convenience is beginning to look like a best-case scenario for both sides.

The Big Play Zone

Beyond the big-picture productivity, the best word to describe the Aggies’ ground game on paper is explosive. That’s in contrast with their efficiency, which is not great; in advanced stat terms, A&M is mediocre or worse as a team in Rushing Success Rate (52nd), Adjusted Line Yards (62nd), and Power Success Rate (103rd).

But what it lacks in down-to-down consistency, it more than makes up for in big plays: Between them, Knight and Williams alone have busted eight runs of 40 yards or longer, a number matched by only two other FBS teams. Altogether, Williams ranks second nationally in yards per carry (8.6) among players with at least 10 carries per game, and Knight ranks fifth (7.7), even after accounting for negative yardage on sacks.

That puts him slightly ahead of the consensus Heisman frontrunner, Lamar Jackson, who’s generally considered the most explosive player in the nation at 7.4 per carry.

On film, the thing that stands out is that almost all of those big runs have come on the same play: A basic zone read staple that exploits Knight’s athleticism and decision-making.

In its four SEC games, A&M has consistently run this play from a shotgun, three-wide set, with an H-back — usually Ricky Seals-Jones, whom defenses must respect as essentially a fourth wide receiver — crossing the formation on an “arc” block that deliberately bypasses an unblocked defensive end on the way to a linebacker.

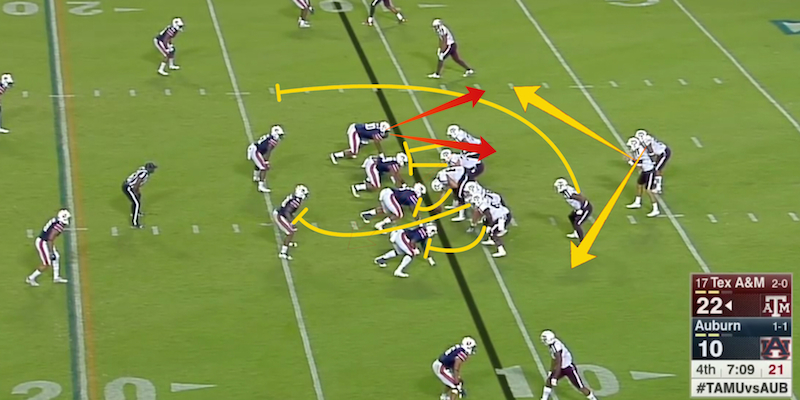

Here’s a pre-snap look against Auburn, setting up the game-clinching, 89-yard touchdown run on which Williams formally introduced himself to the rest of the country:

The concept here is pretty straightforward: At the snap, Knight will read the unblocked end — if the end stays home to contain Knight, Knight gives the ball to Williams running left; if the end crashes down on Williams, Knight keeps it behind Seals-Jones’ block to the right. (Another player to keep an eye on in all of these clips is slot receiver Christian Kirk, No. 3, who frequently bubbles into the flat to serve as a potential “pitch man,” in old-school triple-option parlance. A&M has yet to make effective use of Kirk in that capacity, but it’s worth noting that the option exists.)

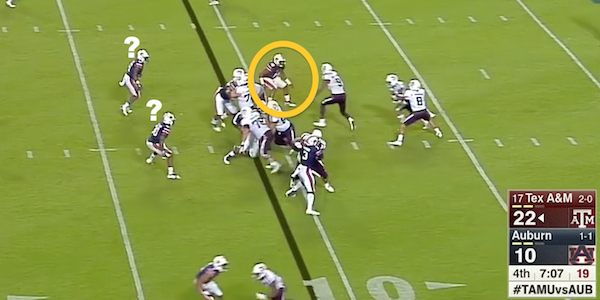

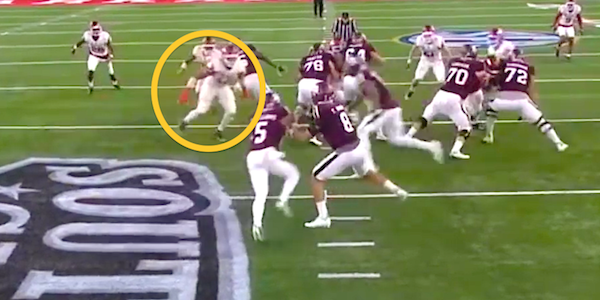

Meanwhile, because the linebackers are keying on Seals-Jones in the same way they would a pulling guard, his path across the formation helps to freeze the backers long enough for them to get caught up in the wash at the line of scrimmage rather than pursuing to the ball. In this case, the end Knight is reading, Paul James III, stays at home to contain the quarterback …

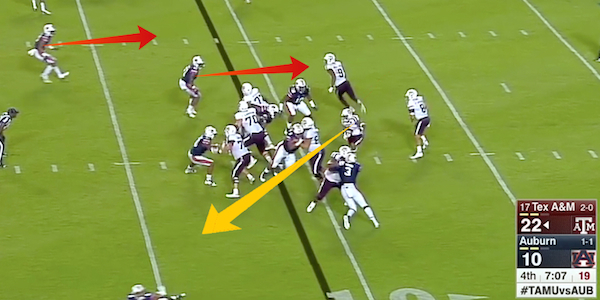

… telling Knight to give to Williams, who is able to spot a nice seam behind center Erik McCoy (No. 64), left guard Colton Prater (76), and left tackle Avery Gennessy (65). It’s Prater, a true freshman, who ultimately makes the key second-level block on linebacker Tre’ Williams (30) to spring his back into the open field.

From which point Trayveon Williams is more than capable of handling the subsequent 85 yards himself.

This play, out of this formation, is the basic template behind the majority of Texas A&M’s biggest runs over the first half of the season. Against Arkansas: The end stays home …

… Knight gives to his former Oklahoma teammate, Keith Ford, for a 27-yard gain.

Later in the first half, the end crashes on Williams …

… Knight keeps it himself for a 42-yard touchdown behind a block from Seals-Jones.

Against South Carolina: The outside linebacker shows contain (and frankly is too far outside to crash the inside run even if he wanted to) …

… Knight gives to Williams for a 49-yard touchdown.

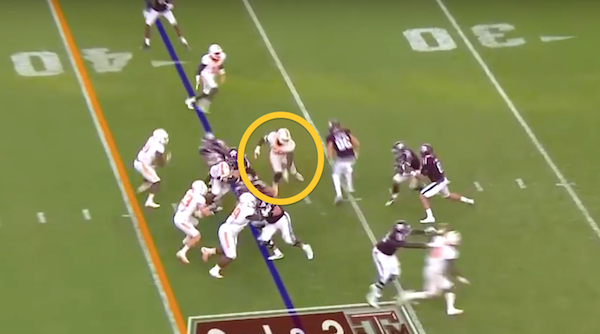

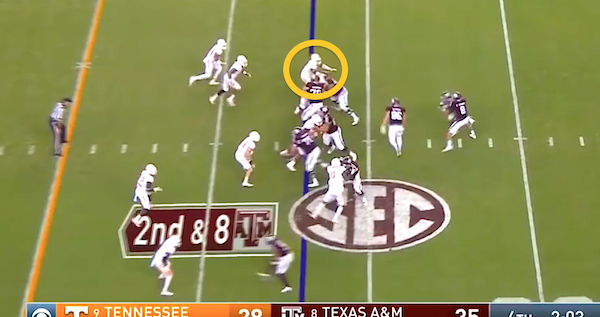

Against Tennessee: The end crashes …

… Knight pulls and finds wide-open spaces en route to a 63-yard score that, in the moment, looked like the dagger in a weird, wild game that was about to get even weirder.

On the Aggies’ next possession following a quick Tennessee touchdown, the end (no doubt chastened by his previous lapse) stayed at home to account for Knight …

… and, two broken tackles later, Williams was off to the races again.

The final result of that run, of course, was a freak fumble — the first of Williams’ college career — and subsequent touchback that set up the Vols for another miraculous touchdown drive to force overtime.

But outside of the specific context of a tight game, the twist ending shouldn’t detract from the larger takeaway: Trayveon Williams is electric in the open field, as lethal a home-run hitter once he reaches the second level as any active SEC back. And sharing the backfield with a quarterback who’s able to inflict as much damage as Knight only makes both of them more dangerous.

Wheels In Motion

A similar way A&M works to open up running lanes is with a heavy dose of pre-snap motion, especially involving Christian Kirk, who (on the strength of 16 career carries for 96 yards) has enough of a reputation as an all-purpose threat to affect edge defenders the same way Knight does on the option.

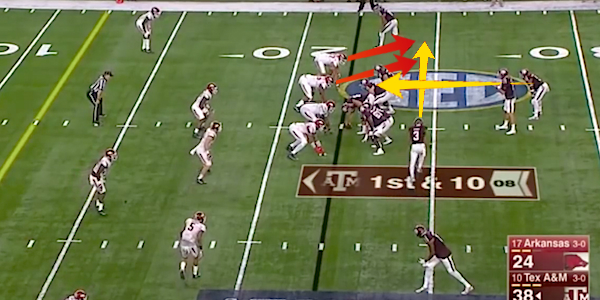

Take this play against Arkansas, a simple inside zone to Williams that largely owed its success to inducing defensive end Tevin Beanum (No. 97) to chase Kirk into the flat in response to Kirk motioning from the slot on the opposite side of the field to an H-back position on Beanum’s side. Not that he had much choice, given that the Razorbacks didn’t have anyone else on that side of the formation to account for an additional receiver.

Not only did Kirk effectively “block” Beanum on this play without laying a hand on him, A&M also caught both of Arkansas’ defensive tackles, Taiwan Johnson (94) and Jeremiah Ledbetter (55), slanting in the same direction, opening up the middle of the field for one of the easiest 22-yard touchdown runs you’ll see against an SEC defense this year:

Against Tennessee, the Aggies opened the game by repeatedly threatening to hand the ball to Kirk on a jet sweep, thereby slowing backside pursuit on plays designed to flow in the opposite direction. On A&M’s second series, the jet sweep action helped open a crease for Williams to gain 11 yards on an outside zone:

On its next series, A&M folded the jet sweep into the read option, allowing Knight to read the backside end (No. 5, Kyle Phillips, who crashes inside) and pick up 16 yards before Tennessee’s pursuit was able to recover from its its initial false steps in reaction to Kirk.

Although he doesn’t make a tackle here, Phillips’ effort in forcing Knight to the sideline actually prevented this play from being a much bigger one; the rest of the defense was so out of position that one more foot of grass before the chalk and Knight might have taken it to the house:

Later in the quarter, the jet sweep action helped facilitate Knight’s only really big completion of the game, a 43-yard strike to Josh Reynolds over a true freshman cornerback, Baylen Buchanan, who had just entered the game due to injury. This time, the pre-snap motion — and the fact that A&M had already had success running off it — helped to hold the safety on Reynolds’ side long enough to keep him from spoiling the mismatch downfield.

The one thing the Aggies didn’t do off the jet sweep action against Tennessee? Actually hand the ball to Kirk. But as long as the threat exists, defenses will have to respect it.

To Saturday and Beyond

Of course, what hold true for other defenses does not necessarily hold for Alabama’s, especially when it comes to establishing the run: The Crimson Tide rank No. 1 nationally against the run (as they usually do), currently allowing more than 20 fewer yards per game than any other FBS team.

Some of that margin is the result of the Tide’s unrivaled pass rush, which has generated more sacks — and more negative yards on sacks — than any other defense, as well, but that only makes them more frightening.

Ole Miss, which runs a similar scheme to A&M’s, had some modest success on quarterback runs and managed to break a zone read for a 23-yard touchdown early in the game; otherwise, trying to run the ball on Bama has been a tale of woe.

If A&M has any chance Saturday, it has to figure out a way to remain balanced and keep Knight out of situations where he’s forced to do too much with his arm. Statistically, he’s arguably regressed as a passer — remove his 344-yard, three-touchdown effort against Prairie View A&M, and Knight ranks 11th among regular SEC starters in pass efficiency against FBS competition, behind the likes of Stephen Johnson, Drew Lock, and Nick Fitzgerald.

His completion percentage, 53.5 percent, is about five points below the national average. Between, Reynolds, Kirk, Seals-Jones, and (when available) Speedy Noil, A&M has a surplus of talent at wide receiver, but much of its passing game this season has derived from run-pass options and low-percentage vertical routes.

In 2014, Knight earned a reputation for killer mistakes, serving up an interception returned for a touchdown in three of Oklahoma’s four losses in which he was the starter. (The only reason it wasn’t a perfect four-for-four is that an apparent pick-six by Baylor was ruled down just short of the end zone; the Bears scored a play later from the Sooners’ 1-yard line.)

Knight hasn’t been victimized on a pick-six this season, but he hasn’t always been the picture of poise under pressure, either: His first attempt against Tennessee was an off-balance prayer with Derek Barnett in his face that fluttered downfield like a pop fly.

Blocking Alabama’s front four is like trying to block four Derek Barnetts; they’ve pressured and hit every quarterback they’ve faced this season in precisely that fashion.

And while Bama’s defensive backs have been vulnerable at times, when they get their hands on an interception they don’t settle for setting up the offense with good field position.

If Knight’s going to avoid becoming the next tally mark on the Tide’s fuselage, it will be because the Aggies got enough going on the ground to keep the chains moving and choose their spots to challenge downfield on their own terms — and even then, only if Knight has learned when to press and when to live to see another down.