Ad Disclosure

Launch Mode: How the home run revolution has changed college softball forever

Editor’s note: This article is part of a 4-part series, “Launch Mode,” in which the Saturday Down South team explains how, in just 20 years, the game of college softball has forever changed. You can see the entire series here.

Softball no longer belongs to the slap hitters. Home runs are all the rage. Records are being crushed, legends are being made. … And there’s no sign this power surge is slowing down anytime soon.

On May 7, shortly after 4 p.m. local time in College Station, Texas, Linnie Malkin took a 1-1 curveball that broke back over the plate just a little too much and smashed it to right field, just clearing the wall and putting the Arkansas Razorbacks up 7-3 on the Texas A&M Aggies. Arkansas had clinched an outright SEC regular-season title the night before, but this Saturday afternoon win was special for other reasons.

As Malkin rounded third and met a trio of teammates at home, she jogged her way into the Razorbacks’ record book. “Oprah mode with the dingers,” the Hogs’ Twitter account said of the hit. It was Arkansas’ fourth homer of the day and it broke the program record for home runs hit in a single season (96).

Some 30 minutes prior and 900 miles away in Athens, Georgia, the Bulldogs broke their program record. Jayda Kearney smashed a 1-2 pitch almost to the same area Malkin hit hers. As it cleared the wall, Kearney set out around the bases for the second time on the afternoon. In the bottom of the first, she hit a 3-run shot that tied the program record at 99. In the bottom of the seventh, she sent flying a grand slam that would break the century mark.

The Bulldogs became the first SEC team since 2015 to hit 100 homers in a season.

The next day, Arkansas hit its 100th homer of the season.

All around college softball, players are going yard, giving scoreboard operators their own kind of workout and rewriting record books.

This season, Mississippi State’s Mia Davidson became the first SEC player ever — man or woman — to hit 90 home runs in a career. She did it against LSU on… May 7.

The sport’s Home Run Queen, Jocelyn Alo, sits on her throne in Norman, Oklahoma, having taken the crown this season from another Sooner. Alo enters the Women’s College World Series with 117 career homers. Arizona State smashed its program record for home runs in a season on May 28 in Super Regional action. (The Sun Devils ended their season with 104.) In a 24-1 demolition of East Carolina on April 30, Wichita State shattered the NCAA record for home runs in an inning by crushing seven in the second. In hitting 10 for the game, the Shockers tied the NCAA record for a game and their program’s single-season record of 103.

“It’s a lot of fun,” Kearney said the week before penning her name in the Georgia record book.

And everyone is in on the fun.

It’s a new game

Twenty years ago, there were two Division I softball programs that averaged at least one home run a game. Prior to that season, only 15 teams had even cleared 1.0 per game in a single season during the NCAA’s official record-keeping, which dated to 1982. Only one of the 15 did it prior to the 1994 season.

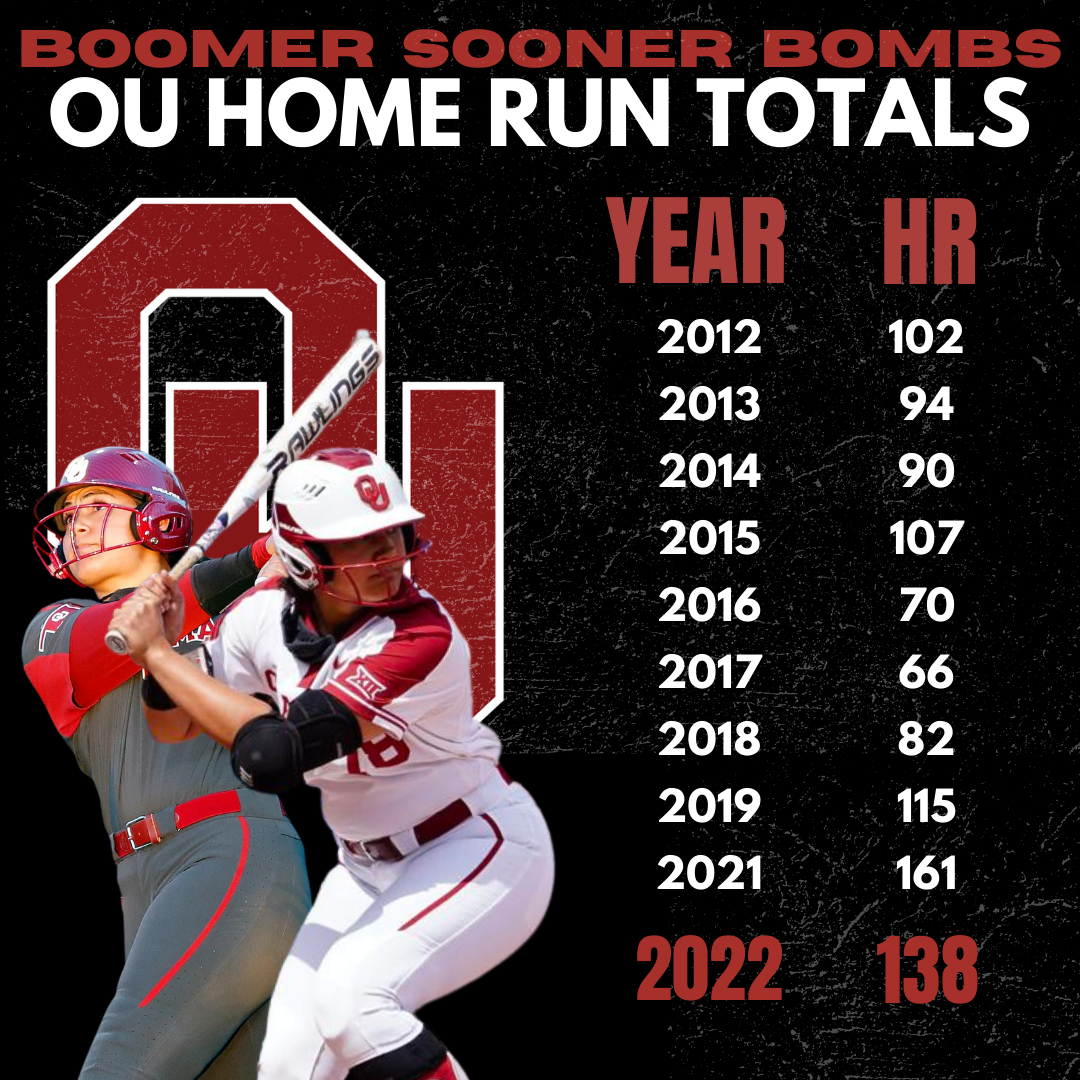

Fast-forward to 2022, and 50 teams average at least one a game (as of May 30). Six of those teams are in Oklahoma City chasing the sport’s grand prize.

Only four teams have ever averaged two a game over the course of an entire season: Oklahoma (2.42) and Wichita State (2.33, season finished) should both clear that mark in 2022 alone. Miami (Ohio) finished its season at 1.97. The Sooners are a threat to break the all-time record, held by the 2010 Hawaii team (2.39). The Shockers and RedHawks will finish with the third- and seventh-best season average in D1 softball history.

SEC teams are in on the sudden power surge, too. Arkansas (1.85), Georgia (1.75), Tennessee (1.54), Kentucky (1.52) and Auburn (1.5) all ranked among the top 15 nationally in home runs per game. The league smashed a record 941 home runs this season — besting the previous mark set in 2015 by nearly 100.

The change, just in these players’ lifetime, has been dramatic.

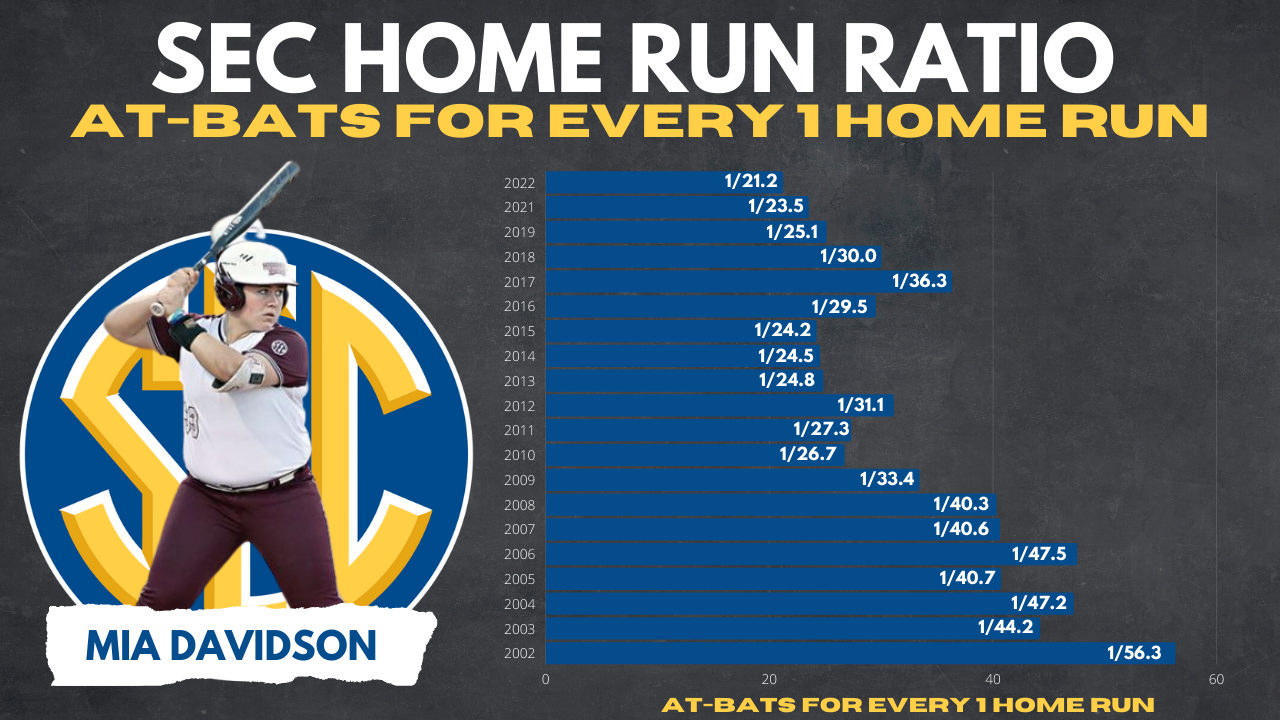

In 2002, softball was a significantly different sport. One where 3-2 games were commonplace and runs came courtesy of slap hits to the opposite field. In the SEC, there was a home run every 56 at-bats, according to Saturday Down South’s research.

Five years later, SEC teams homered every 41 at-bats.

Five years later, they homered every 31 at-bats.

This season, SEC teams hit a home run every 21 at-bats.

There’s no reason to think this trend will slow in the coming years, and when the SEC soon adds its two newest members — Oklahoma and Texas — get ready for even more juice. This season, the Sooners are averaging a home run every 10 at-bats. They’ve run-ruled opponents in 38 of their 56 games leading into the WCWS — including a ridiculous stretch of 13 straight from March 7-26, the first 12 of which included a homer.

On May 22, Oklahoma demolished Texas A&M 20-0 to push through to the Super Regionals. On a dry, hot day, OU fans poured into Marita Hynes Field to be subjected to five innings of flame-thrower offense. The crowd was barely settled into their seats when Oklahoma smashed the pedal through the floorboard with a nine-run first inning that lasted more than a half-hour. The entire order made its way to the plate. The sunburn had already set in.

Alo, softball’s all-time home runs leader, batted second for OU. Her first chop went deep to left field but fell a few feet shy of leaving the park. When things worked their way back around to her for a second plate appearance in the inning, there was a murmur in the crowd.

An expectation.

Oklahoma was rolling. Surely A&M wouldn’t pitch to Alo again, right?

It did.

And Alo made amends for leaving her first hit short.

Same spot. More air.

Alo cranked her 115th career homer to put the Sooners up 9-0 before A&M’s offense even set foot on the diamond. The crowd knew it the instant it left her bat. Sooners coach Patty Gasso doesn’t ever wonder “is this going to be the one?” but she knows her superstar is going to get at least one more often than not.

After the game, as she was walking away from the media tent, Gasso was told her team had outscored opponents 103-2 in all first innings to that point in the season. It stopped her in her tracks, but she didn’t look shocked. No, the look was more what-else-is-new than anything. “Our players do things,” she started, “if I put it all together, I’d be like, ‘Wow,’ so I don’t even pay attention to it.”

If she kept track of records, she’d constantly be scribbling.

Building the perfect slugger

Alo is now more than 20 homers clear of second on the sport’s all-time leaderboard. She took the record from another former Sooner this season, Lauren Chamberlain. In 28 years as Oklahoma’s head coach, Gasso has built the program into an undeniable force. She just laughed at the suggestion she could have another record-breaker five years down the road. Maybe she’s already found one — sophomore Tiare Jennings already has 51 career home runs. Maybe the Sooners have another Alo coming through the pipeline. Because make no mistake, another is coming.

The OU coach outlined three areas of change she thinks have led to this hitter’s paradise: strength training, better technology when it comes to equipment and analytical investment. All three point to one common denominator — investment in the sport and the women who play it.

“100 percent,” she told me. “I think so, yeah. … As the game grows, opportunities and money toward these games and leagues will grow as well.”

And you’ll see more like Jocelyn Alo. Girls now grow up watching Alo and her contemporaries crushing it on ESPN.

The sport’s biggest names are magnified. The coverage is growing. Holly Rowe is the new Kirk Herbstreit.

Capital investment is up. Interest in the sport is up.

“I think some youth programs definitely have those kinds of coaches that are kind of ahead of the curve,” Gasso said. “It’s starting when these kids are 12 years old, learning how to swing correctly, how to field properly, they’re bringing in former college athletes to train and teach these kids, so it’s out there.

“I see these athletes become much stronger in their core and legs, and then understanding where we need to get strong. I think 25 years ago, we didn’t really know. It wasn’t the obvious that it is now.”

Around 2015, Gasso says OU fully embraced analytics as a tool to help the program.

“It’s really helped make us who we are,” she said.

The Sooners partner with a number of companies that feed the program all kinds of information. Swing speed? Yes. Exit velocity? Yes. Launch angle? Yes.

“I’ve got to credit my son who’s my hitting coach, JT Gasso,” the OU head coach said. “He’s like a scientist of hitting. He likes to look into everything from major league baseball hitters and how they swing, to the analytics side, to the breathing and the mental side. We just cover everything you could ever imagine.”

One of the program’s partners is a company called Rapsodo, with training devices that have captured and analyzed over 22 million hits and 16 million pitches. It’s a data company that claims to help 1,000 collegiate partners and NCAA champions beyond just the Sooners.

During a webinar with the company in early 2021, Mississippi State head coach Samantha Ricketts said her program will put players through a week-long assessment period to screen for mobility, various bat metrics and ball metrics to get a baseline average for what each player’s swing looks like, what the contact quality is like, and then areas of strength or weakness.

“From there, each hitter is going to get some sort of individualized (program) where they’re going to work on, for example, if my focus is bat speed/exit speed, I need to be above my average exit velocity in 70% of my swings,” Ricketts explained. “They go in, (data) is pulling up on the TV after every swing, and they know they’re going for four out of six, or whatever their average might be, on every round. It creates a little bit more of a competitive environment and definitely a more focused environment for our hitters and (let’s) them know what they’re working on, why, and then to see the results automatically. … It’s a really tight feedback loop. For us, that’s really important for them to continue to grow.”

JT Gasso said during that same webinar that OU used, for example, bat-tracking technology from Rapsodo to track exit velocity for each player on different speed pitches.

“It was pretty cool because a lot of the freshmen just have no idea what they’re getting themselves into, have never seen different speeds or spins, and so tracking that over the course of a semester was huge for us,” he said.

Ricketts likes to use a launch angle ladder drill.

A batter has to work her way up and down the “ladder” at different launch angles. Hit zero degrees, then 10, then 20, then 30, then work your way back.

“Can you make the swing adjustment? Do you understand how to make the adjustment? Then you can start to compare it to, alright, that’s your hit-and-run angle, if we’re facing a rise-ball pitcher you’re going to need maybe your 10-degree or your zero-degree launch angle, a drop-ball pitcher we might be working more 20-30 degrees,” Ricketts said. “It started to help them understand a bit more of our game-planning and our approach to different types of pitches.”

Georgina Corrick, an ace pitcher for USF and one of three finalists for USA Softball’s Player of the Year award, sees hitters getting smarter. Technological advancements — and access to them — have given batters an edge.

”My friend, she just partnered with a brand that allows you to put virtual reality headsets on and see another pitcher,” she told Saturday Down South. “Like, if they were able to get enough data off of me, they could recreate me virtually. You could take 50 at-bats off me before you ever saw me, which is incredible. I think it does put a little bit of the benefit in hitters’ hands.

“Girls are getting smarter. We’re getting a lot smarter when we play, a lot smarter when we swing, and I’m having to get a lot smarter to catch up and beat them every single time.”

Corrick sees the same kind of swing in hitters up and down the lineup. To a degree, that helps her. You give up a solo shot in the second inning, but see the same tendencies 1-9 in the order, and it’ll give you a bit more confidence moving forward.

But it also trims the margin for error. You have to work the outsides of the zone. You miss twice in 100 pitches and those two misses could now cost you.

“I see a lot more girls swinging with a little more power,” she said.

Investing in the future of the sport

It’s a power that’s rooted in research. That kind of data, though, and that kind of technology requires investment.

In October 2021, OU announced it had secured a naming gift to help build a brand new softball stadium from the Oklahoma-based Love’s Travel Stops. Between the initial donation and a promise to match, it marked the largest financial gift toward a female sports program in OU athletics history, according to the OU Daily. The $27 million stadium is expected to be state-of-the-art throughout the sport. It’s scheduled to open in 2024, in or around the time the Sooners begin play in the SEC.

The program had announced initial plans to build a new stadium four years prior, in 2017.

Around that time, softball was the NCAA’s fastest-growing sport.

According to data from the Department of Education from 2017-18 (the last year data was reported), Division I softball programs across the country reported nearly $500 million in revenue. In 2003-04, the earliest date of reported earnings from the Department of Education, no one reported revenue north of $1 million. In 2018, 70 teams did.

Last season, the 2021 Women’s College World Series outpaced the men’s tournament in viewership by 60 percent, according to Shot:Clock Media. The women’s tournament drew, on average, 1.2 million eyeballs, nearly 500,000 more than the CWS. Viewership was up 10% from the 2019 WCWS (COVID canceled the 2020 tournament) and broke a record for the most-watched WCWS ever, according to an ESPN release. The three-game championship series averaged 1.8 million viewers, up 15% from its 2019 counterpart.

From a marketability standpoint and from an ad-sell standpoint, Corrick thinks more home runs are absolutely good for the game. “Now, finally we’re going to post … these highlight reels of girls absolutely mashing balls and suddenly we earn that respect.”

Growth and investment matter.

Gasso talked about the ability to earn a living playing professional softball in Japan, and earn a good living.

Perhaps the sport will soon be able to say the same can be done here. Chamberlain, now the commissioner of the new WPF — Women’s Pro Fastpitch, a professional softball league beginning play June 2022 — is certainly working to try and make that a reality, and doing so in partnership with USA Softball.

It’ll look to get up and running from Oklahoma City, the softball capital. The 2022 Women’s College World Series will begin play on Thursday, June 2. Gasso, Alo, and the Sooners will look to defend their 2021 title. Some of the top hitting teams in the country will look to knock them off.

Know there will be home runs. Know there will likely be many. And know they likely won’t yield anytime soon.

Executive Editor Chris Wright contributed to this report.

Derek Peterson does a bit of everything, not unlike Taysom Hill. He has covered Oklahoma, Nebraska, the Pac-12, and now delivers CFB-wide content.