Ad Disclosure

Launch Mode: How the best pitchers in America are dealing with softball’s power surge

Editor’s note: This article is part of a 4-part series, “Launch Mode,” in which the Saturday Down South team explains how, in just 20 years, the game of college softball has forever changed. You can see the entire series here.

If you didn’t know any better, you might listen to Georgina Corrick speak about the rise of home runs in college softball and assume she was a power-hitting corner infielder. That’s not the case. At all. The University of South Florida star pitcher led the nation in strikeouts and broke the program’s all-time record for career whiffs, but there’s a macro issue that she believes is a positive for the future of the sport.

The long ball? Yeah, it sells.

“From a marketing and from an advertising standpoint, it’s massive,” Corrick told SDS. “You look at the coverage that (Oklahoma star) Jocelyn Alo gets on ESPN, not just ESPNW. She leads not just NCAA softball in home runs. She leads NCAA softball and NCAA baseball in home runs … now finally we’re gonna post these things on Twitter, we’re gonna post on Instagram and Facebook, and these highlight reels of girls absolutely mashing balls. Suddenly, it feels like we earned that respect.

“It’s cool because it finally translates into other things that people care about. They care about the big home runs. They care about the nukes. They care about all of those things like that … home runs will always take the cake because they seem a little more impressive in the moment.”

JOCELYN ALO GIVES @OU_SOFTBALL THE LEAD IN THE 6TH ‼️#WCWS pic.twitter.com/37wE2h9A9n

— SportsCenter (@SportsCenter) June 10, 2021

Corrick was 1 of 3 finalists — and the only pitcher — for the 2022 USA Softball Player of the Year Award. The other 2 finalists were sluggers. Of course. Alo, the NCAA’s all-time home run leader, won the award for the 2nd year in a row. Washington’s Baylee Klingler, who finished tied for 4th in the country with 24 home runs, was the other finalist.

Corrick only allowed 12 home runs during her All-American senior season. That’s the same number that legendary ace Jennie Finch allowed during her All-American senior season at Arizona in 2002. But don’t get it twisted. The game has changed significantly in the past 2 decades.

In 2002, only 2 Division I teams averaged 1.0 home runs per game. Twenty years later, 50 Division I teams averaged at least 1.0 home runs per contest.

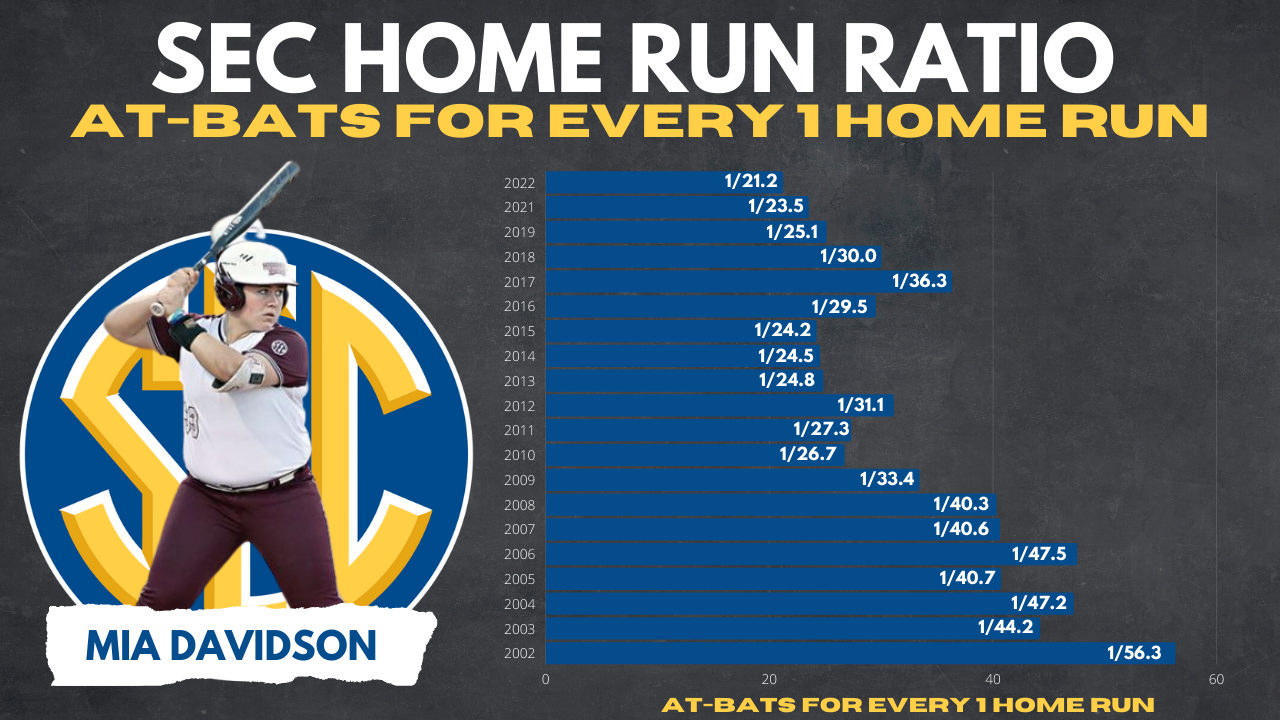

In 2002, there was 1 home run per every 56.26 at-bats in the SEC, for instance. Twenty years later, there was 1 home run per every 21.2 at-bats in the SEC. That’s a lower ratio than SEC baseball teams posted in 2022.

The power surge is reflected in the team pitching numbers, too. In 2002, there were 30 Division I teams with an ERA of 1.46 or better compared to just 3 teams in 2022.

It’s not just rotational pitchers getting hammered, either. Alabama All-American Montana Fouts, who threw a perfect game in the WCWS last year, gave up 10 home runs this season. Auburn ace Maddie Penta, who tied Fouts for the most wins in the SEC, surrendered 15. Thirty-three SEC pitchers gave up at least 10 home runs.

The game has changed. Go figure that happened with basically identical strikeout rates to what college softball had in 2002. So how did Corrick handle that? Better yet, how does a future college pitcher handle that? And will that slow down anytime soon?

The simple answer is to adapt. That’s what Corrick prided herself on in college. She added 4-6 MPH of velocity — she admitted she could throw harder but has her best control in the high 60s — and added a new pitch to her arsenal every offseason. A knee injury took away her drop ball effectiveness, so she turned to the screwball as a sophomore. The next year it was the changeup, then it was the rise ball.

When she was a drop ball, curveball pitcher in high school, Corrick would keep pitches low and get strikes off of the plate. She’d occasionally give up home runs to power lefties, and she didn’t really have a changeup. Teams would rely on craftier ways to win. Stealing bases, pushing runners from station to station and capitalizing on a throwing error meant that from a pitching standpoint, home runs weren’t emphasized the way they are now.

“You can move those fences as far as you want. Jocelyn Alo is still gonna hit one out.”

In high school, Corrick never ran into a team quite as powerful as Wichita State, which finished 2nd in Division I to Alo’s Oklahoma squad with 121 home runs. Earlier in the year, Wichita State hit an NCAA record 7 home runs in an inning. It was the second consecutive year that the Shockers surpassed the 100-home run mark.

In the 3-game USF-Wichita State series, Corrick pitched 15 innings and allowed 9 hits and 3 runs, all of which came from solo home runs. In the lone loss she took in the series, Wichita State had 2 solo home runs to squeak out a 2-1 win. Still, Corrick still came away with a successful showing against the Shockers for the second consecutive year. Against the high-powered Wichita State bats in 2021, she dealt 3 consecutive complete games and surrendered just 2 runs on 8 hits (she also had a total of 29 strikeouts in the 3-game set). She credited that to knowing that Wichita State swung expecting the rise ball and she had to mix up her speeds even more than usual.

“Over my last 10 years of pitching, I’ve seen a lot of different styles of hitting,” Corrick said. “Sometimes, you’ll have a team where all of their swingers kind of swing the same. What happens is early in games or if I’m behind in a count, I can give up a solo bomb or something like that. But I find I have a little more success because I’ll see their swing and see the same exact swings 1 through 9.”

That philosophy allowed Corrick to hold Mississippi State star and SEC all-time career home run leader Mia Davidson to an 0-for-3 clip with 2 strikeouts. Davidson finished No. 3 on the all-time Division I home run list with 92 career homers. The top 5 on that list, by the way, all ended their careers in 2014 or later. That includes the leader Alo, who has 117 career home runs (and counting) entering the Women’s College World Series.

So is that a sign that a change needs to be made to give pitchers more of a chance?

“You can move those fences as far as you want,” Corrick said, “Jocelyn Alo is still gonna hit one out.”

Fair. But what about the bats? Has improved technology led to an unfair advantage for the hitters or is there perhaps a direct correlation with a specific bat? Not so much, according to Corrick.

“You can’t always blame the bats because you could look at 3 of the best hitting teams in the country — Oklahoma, Arkansas and Wichita State — and all 3 of them swing different bats,” she said. “You can’t always say, ‘Oh, they’re swinging The Ghost. That must be the hottest bat on the market right now.’ A lot of it has to do with swing dynamics and how you swing a bat.

“From a pitcher’s standpoint, I know that certain balls come off the bat and I’ll go, ‘That’s a hot bat. That doesn’t sound right.’”

Technology is something Corrick called “a constant horse that you have to chase and if you’re left in the dust, you’re left in the dust.” From a pitching standpoint, there’s only so much she can do if a hitter had enough data on her to simulate at-bats with a virtual reality headset. Twenty years ago, Finch never had to worry about stepping into the circle wondering if an opposing lineup had simulated 50 at-bats against her. Corrick said she does. It’s still a mind game, albeit with different factors at play.

It’s also why she admittedly devoted more time to the psychological aspect of pitching in this home run-driven era. Corrick and USF catcher Josie Foreman constantly talk about pitching. Whether it’s discussing spin, break or counts, Corrick said she sometimes benefits more from a 15-minute chat with her catcher than a 100-pitch session. That’s what allowed them to call their own game together.

Talent can only get you so far as a modern-day pitcher, especially with the way bats are being swung in the long ball era.

“As long as the bats are getting hotter, as long as the pitchers keep throwing harder, you’re gonna hit more home runs,” Corrick said. “Until somebody is like, ‘Hey, I think girls are gonna get hurt,’ technology is gonna stay the same.

“Girls are just gonna have to keep getting better.”

Executive Editor Chris Wright contributed to this report.

Connor O'Gara is the senior national columnist for Saturday Down South. He's a member of the Football Writers Association of America. After spending his entire life living in B1G country, he moved to the South in 2015.