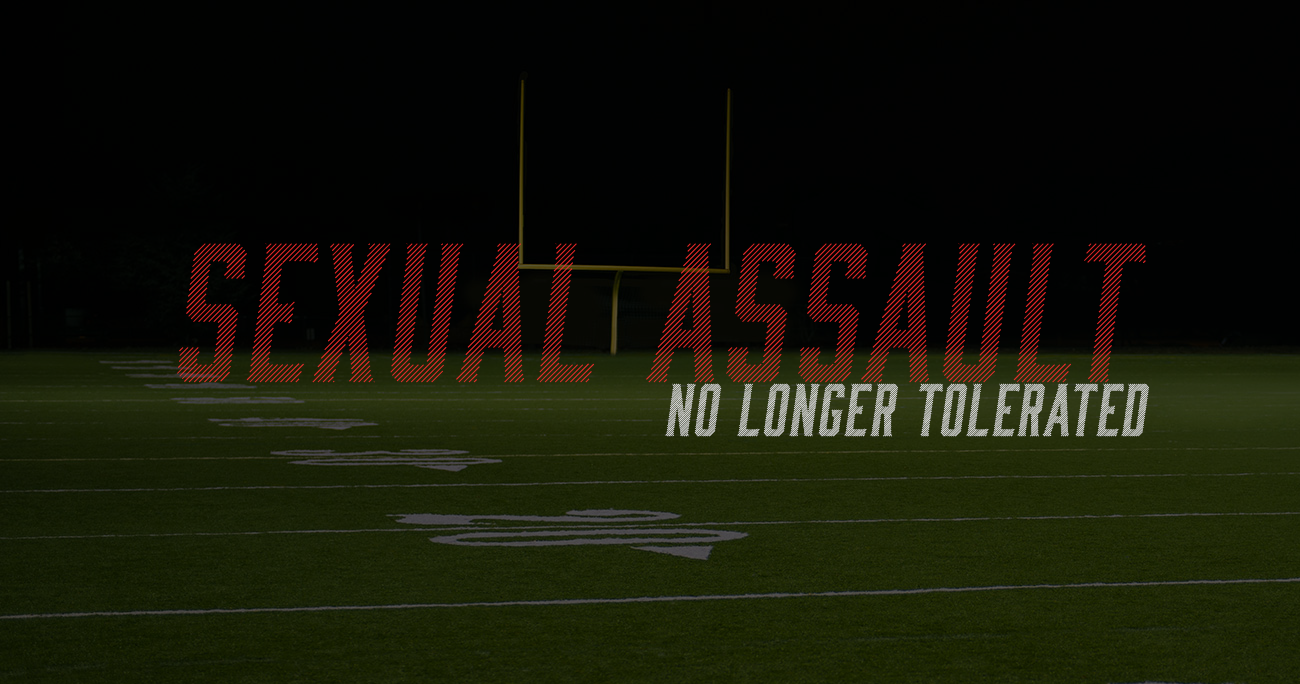

Chances are your favorite SEC football media company has inundated you with headlines in the last two weeks about the happenings in Knoxville. A group of women have filed a Title IX federal lawsuit alleging institutional failure which made female students vulnerable to sexual assaults.

For those of you that like your football news to be a little more uplifting and enjoyable, it’s not exactly a good time. But it also represents real progress.

Ten years ago, if a football player committed sexual assault, chances are the public would never hear about it.

It’s one of the most complex violent crimes to investigate or prosecute. Someone gets murdered, inevitably there’s a body or a missing person that forces law enforcement to seek answers. Someone gets physically assaulted — with fists or a weapon — and often there’s either a loud argument involved or clear signs of physical trauma.

The public perception of guilt or innocence in those types of cases is more often straightforward. We generally do not tolerate, excuse or justify shooting someone dead.

Sexual assault is without a doubt a physical crime, usually of the most intimate nature. But it’s also an emotional one, with victims often experiencing a high degree of shame.

Perhaps an unwanted sexual act involves alcohol or drugs. Perhaps it’s a case of someone putting themselves in a 1-on-1 situation that in hindsight they’d prefer not to disclose. Perhaps the victim cannot remember every detail of what happened. Or perhaps the victim simply does not want to have to go through an invasive pelvic exam or have to re-live a terrifying, horrible moment through a drawn-out legal process that may or may not result in justice.

For a variety of reasons, sexual assault is one of the most underreported crimes. When it is reported, it can sometimes be difficult to prove and turns into a he said, she said sort of thing.

When the accused plays football for a college or NFL team — well, as a victim, you’re inviting all sorts of public scrutiny, not to mention the fear that the institution will protect the player.

To an extent, the media and the public are complicit in this, often taking apathetic stances toward allegations of sexual assault. Or just steering clear, metaphorically crossing on the other side of the street.

The fact that Tennessee’s coaches felt compelled to stage a 16-person joint press conference to address the perception of sexual impropriety on the part of its athletes is just the latest public indication that times are changing.

Several Tennessee football players past and present have been accused of anything from “mooning” a trainer to rape. Coach Butch Jones even was accused of verbally berating a player for helping one of the alleged victims (including the use of the word “traitor”), though he made a strong denial and the university has stood behind him.

There’s been enough public and media attention that the Vols seem seriously concerned that public perception is going to put them at a major disadvantage athletically, both in recruiting and donations.

https://twitter.com/Volquest_Paul/status/702154175333924864?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

Jones: We're being stereotyped here, and I take it personally. We've had some kids make tough choices, but we have great character kids.

— Wes Rucker (@wesrucker247) February 23, 2016

That level of tangible pressure to police the culture and ensure that it’s a safe, fair environment would not have existed in the not-so-distant past.

Several former Vanderbilt football players continue to face rape charges after a mistrial in 2015. In the midst of this, the Commodores also tweeted out “We don’t need your permission,” a quote attributed to coach Derek Mason seemingly intended as a statement about the direction of the football team on the field.

Public reaction to the insensitive word choice was swift and exceedingly harsh.

There have been other recent cases that drew a large amount of publicity — Florida’s Treon Harris was accused, but his accuser eventually withdrew her complaint.

Outside the SEC, then-Florida State quarterback Jameis Winston was named in one of the most infamous rape accusations in college football history, though he claimed consensual sex and no charges were ever filed.

Though their incidents were not sexual in nature, NFL running backs Ray Rice (video of him dragging his unconscious fiancee out of an elevator after apparently punching her) and even Adrian Peterson (evidence he took corporal punishment way too far with his 4-year-old son) got publicly excoriated for physical acts against a woman and a child. Both cases seemed to signify a changing public conscience that forced the league to change its politics and policies.

The big discussion this month has been about whether or not Peyton Manning acted inappropriately toward then-trainer Jamie Naughright — on Feb. 29, 1996, almost 20 years ago.

In some of these cases, the facts are unclear. This is not to argue for or against the guilt or innocence of any particular player, team or accuser. Neither is it to back or oppose any number of media members exploiting this story for their own personal gain.

But two general trends have emerged throughout these recent developments related to the issue of sexual assault and football.

- Student-athletes or NFL players often are unfairly coddled or protected beyond what a normal accused citizen can expect.

- The media and the public no longer seem willing to tolerate such behavior or to leave it unexamined.

Sexual assault is a nasty business that often leaves life-long emotional scars. Almost all of us know someone very personally who has been directly affected by it.

Not every accuser is in the right, and not every accuser is honest. But it takes real bravery to admit an assault has taken place even if the perpetrator is an average citizen. Even more so if the accused is a famous or well-liked football player.

Reviewing the process through which SEC and other universities handle such cases, which seems to be taking place with regularity, is long overdue. Athletes should not get preferential treatment when it comes to fighting these charges, not if it means bullying or creating road blocks toward women who are going through a difficult trauma.

No matter what you think about any specific case or accusation that has surfaced in the last few years, we should all embrace the fact that this dark closet of our society finally is getting a light shined in its direction.

An itinerant journalist, Christopher has moved between states 11 times in seven years. Formally an injury-prone Division I 800-meter specialist, he now wanders the Rockies in search of high peaks.