How Tua Tagovailoa defied the scouting report to launch his championship-winning TD pass

By Clint Lamb

Published:

Alabama’s second-half comeback was epic to say the least. Twice, the Tide trailed by 13 points. With each passing moment, the chances of a comeback seemed more and more unlikely.

Yet, no one on the Alabama sideline believed that. As a result, they were able to claw their way back into striking distance and ended up sending the game into overtime — after missing a 36-yard field goal at the end of regulation.

Then Rodrigo Blankenship opened overtime by making a 51-yarder to give the Bulldogs a 3-point lead. Georgia’s defense followed with an impressive first-down play where they sacked Tua Tagovailoa for a 16-yard loss — making it 2nd-and-26.

It was dire.

That’s when it happened …

Tua Tagovailoa to DeVonta Smith for the CHAMPIONSHIP!!! #NationalChampionship pic.twitter.com/BRFqFp511T

— DRK Sports (@drksportsnews) January 9, 2018

The former 5-star from Hawaii took the shotgun snap, held the safety on the hash by looking right and then delivered a perfect 41-yard strike down the left sideline to fellow freshman DeVonta Smith. Game, set and national championship.

The pass couldn’t have been any better. But how did it happen? What led to Smith being so open on that final play?

There were actually several factors.

The first was somewhat unintentional. Due to the sack by Jonathan Ledbetter on the previous play, the ball was put on the left hashmark. That might not seem like a big deal, but it was a huge factor in how the winning play transpired.

On the play that Alabama called — “Seattle,” which was essentially “four verticals” — the formation is set up where the trips (the side with three receivers) is to the wide side of the field. Based off the sack, that put trips on the right of the formation.

That might not seem like a big deal, but that obviously creates a situation where Georgia has focus more on that side because Alabama has more weapons there.

On top of that, Tagovailoa’s success earlier in the game — in addition to what we know about most left-handed quarterbacks — had Georgia more weary of the right side of the field.

Why?

Well, check this out. Here’s a look at every pass Tagovailoa made in the National Championship Game:

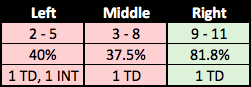

Now, here’s a breakdown of the success rate he had going to each section — left, middle and right — of the field:

It’s evident that Tagovailoa was 1) more comfortable throwing to the right side of the field and 2) he had a much higher success rate throwing to the right side as well. This isn’t surprising when you consider that he’s a left-handed quarterback, but it did play a huge role on that final play.

Kirby Smart and the rest of the Georgia defense understand that left-handed quarterbacks typically prefer throwing to the right because it doesn’t require resetting the feet and shoulders. It’s easier and more natural to step into those throws.

Considering Tagovailoa had only thrown 4 of his 23 passes to the left, that concept was magnified.

There’s other evidence to back up this idea from previous games as well — it just isn’t as compelling. This isn’t to say that Tagovailoa isn’t effective throwing to the left. Six of his 11 touchdown passes this season were to his left, though none of those throws traveled more than 24 yards in the air. The rest were short fades and designed rollouts.

His most dramatic TD passes during the regular season were to the right, where lefties can more naturally step into the throw. Like this one against Vanderbilt:

Tagovailoa’s first TD against Vanderbilt. pic.twitter.com/OjWIxBq15T

— Clint Lamb (@ClintRLamb) September 26, 2017

It was apparent Tagovailoa was more confident going to his right in Monday night’s game. The play calls from offensive coordinator Brian Daboll supported that as well.

The combination of Tagovailoa’s preference and which hash the ball was placed on created a perfect storm, if you will.

Tagovailoa essentially made a throw he hadn’t made all season.

Then, you can add in the subtle head nod by the receiver Smith on Georgia’s Malkom Parrish — making the cornerback believe he was fighting for outside position. It might not have seemed like much, but it created just enough where it took Parrish a tick longer to turn his hips inside — thus creating separation.

After that, it was simple.

All Tagovailoa had to do was look off safety Dominick Sanders and put the ball in a spot where Smith could bring it in — both of which he did to perfection.

Clint helps cover the SEC West for Saturday Down South. His work can also be found on USA TODAY Sports, The 'Bama Beat podcast and The Bullpen with TonyMac and The Lamb. Previous stops include SEC Country, 247Sports and Touchdown Alabama Magazine.