38 Days: How Alabama Pulled off the Great Heist of Nick Saban

By Al Blanton

Published:

Editor’s note: This story originally published in 2017 as part of Saturday Down South’s 15-part series on Nick Saban’s “Decade of Dominance.” Saban announced his retirement on Jan. 10, 2024 after 17 years at Alabama.

“As we recently “celebrated” our 45th wedding anniversary over a morning cup of coffee before Nick headed in to the office, we did a quick reminisce of our marriage, which can be titled by chapters of football jobs and our two children who hailed under different team colors. We ended our abbreviated journey through college and pro jobs so that Nick could leave for the Mal Moore football office to continue preparations for the final four game in Atlanta. Weather channel posted 6:30 on the dot, “Gotta go.” Nothing has changed. A few more gray hairs and stiff knees, but the thrill of the competition is every bit as powerful and keen as the first game he every played or coached.”

-Terry Saban in an email to Saturday Down South

A transcript of the proceedings might read like an FBI case file. Helicopters swarming. Reporters emerging from shadowy streets. Intermediaries. Rumored meetings. Faux search committees.

By the end of the odyssey, the hiring of Nick Saban at Alabama would require a private plane, a limousine company, and a driver named Francisco. Secret meetings would be held in Tuscaloosa, New York, Fort Lauderdale and a laundry room. But what happened across the 38 days between the firing of Mike Shula and the hiring of Nick Saban would prove to be the fulcrum on which Alabama football swung. “It was one bizarre event after another,” Steve Townsend, a retired special assistant to Mal Moore, recalled during a series of interviews with Saturday Down South.

For a decade, Alabama football had experienced the most tumultuous era since the unremarkable J.B. “Ears” Whitworth days of the 1950s (a time when the athletic dorm was referred to as “Ape Dorm” to underscore many of its Darwinian inhabitants). The flux from January 1997 to January 2007 included a 1-9 record against Tennessee, a 3-7 record against Auburn, a 3-7 record against LSU, and losses to a murderers row of also-rans: Kentucky, Central Florida, Louisiana Tech, Northern Illinois, and Southern Miss. A new paradigm of high turnover and NCAA sanctions had shifted the Tide from elite program to laughingstock. If anything, the Shula hire brought stability (but not wins) and by late November 2006, Alabama sat at a paltry 6-6 and was looking forward to another Shreveport-esque bowl.

***

Few events, if any, leading to Mike Shula’s exodus are surmountable to the Nov. 4, 2006 loss to Sylvester Croom’s Mississippi State, a defeat that sounded the proverbial death knell in the minds of many (even some dyed-in-the-wool ‘Bama fans were hoping for a loss). “The Mississippi State game tilted that whole deal in another direction,” Townsend told SDS. “Animosity had reached a boiling point.”

Yet even with the crimson-faced losses piling up, insiders suggest that if Shula could have somehow defeated Auburn on Nov. 18 his services might have been retained. Instead, Alabama lost its fifth in a row to the boys from the Plains — a school record — and on Monday, Nov. 27, ‘Bama’s Golden Boy was fired.

“It’s always been about the competition, the challenge. That’s the glue that holds it all together … the thread that binds the experience, the knowledge, and the ‘process.’ So it was after five years at LSU of building that program and turning it around, when Wayne Huizenga came calling, literally at our door on Christmas Eve, having flown in on his private jet to have a talk about coaching his Miami Dolphins. We knew better.”

– Terry Saban to SDS

Mal Moore, the embattled athletic director who had overseen the Barnum-and-Bailey-like “Fran-pri-shula era” (where coaches zipped by like horses on a carousel), was forced into the breach once more. The old soldier had been lanced thrice — the untimely departure of Dennis Franchione to Texas A&M, the short and sad tenure of Mike Price, and now the doe-eyed Shula November — and was being pummeled by naysayers and members of his own flock. By November 2006, Alabama wasn’t tacking on to its legacy; Alabama was building a crypt.

After Shula’s heave-ho, Moore immediately cobbled together a caucus tasked with finding a martinet Alpha Dog who had a proven track record of success and a “championship pedigree.” From that jumping point, two candidates immediately sprang to mind: Steve Spurrier and Nick Saban. And from the outset, Saban was Moore’s prized steer.

On Day 1 of his search, Tuesday, Nov. 28, Moore clandestinely put out feelers for both Saban and Spurrier, gauging interest through various channels. A private headhunting firm headed by Chuck Neinas was also retained by the athletic department for a fee in the neighborhood of $35,000. But many wondered if the fading glory that was Alabama football could still rely on its name for the big haul. It didn’t have much else.

After Shula’s disappearance, Alabama installed as interim coach the raspy Joe Kines, who would direct the Tide against the Oklahoma State Cowboys in the mighty PetroSun Independence Bowl in — yes — Shreveport (sigh) on Dec. 28. Ultimately, Kines didn’t have a snowball’s chance at the job, but he accepted his interim tag with grace and without complaint.

Because Moore and the Head Ball Coach were acquaintances from the olden days, Spurrier was the more easily accessible of the top two candidates. More than once, Moore talked to Spurrier over the phone, but Spurrier quickly reemphasized his commitment to building South Carolina into a viable SEC program. Conversely, Moore did not know Saban personally, but he had developed a remote admiration as Saban’s coaching stock continued to ascend. “He was a Saban admirer,” Townsend told SDS, speaking of Moore. “He liked the way he handled things.”

Moore decided that all dialogues involving the next coach would be kept close to the vest. The internal discussions in the athletic department were often so surreptitious that Moore would warn members of his staff — for their own sake — not to utter a word. Ronny Robertson, Major Gifts Director of University Athletics and a close advisor to Moore, recalled such a story in a conversation with SDS: “One day I said, ‘Mal, I heard Spurrier turned us down.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Don’t be telling everybody that. I’m just reminding you for your own good that somebody’s going to ask how it got out and I don’t want it to come back to you.'”

With Spurrier crossed off the list (at least for now), Moore’s gape centered on Saban. But what gave him an inkling that Saban might leave the Dolphins in the first place? The answer? Fate.

“After stints in both college and pros, we had a pretty good idea that Nick’s best fit was college. His recruiting, his love of developing the young players, the whole college community of alumni and feeling of family was where we belonged, and I, as the coach’s wife, could participate and contribute, along with our children and feel like a part of the community.”

-Terry Saban to SDS

The summer of 2001. After Saban was hired at LSU, he and his wife Terry bought a home at Lake Burton, Ga. Soon the Sabans began looking for a reputable contractor, and that’s when Chuck Moore came into the picture. Chuck was a housing contractor in the area, and a good one. Initially Chuck didn’t reveal to Saban one significant piece of information: Chuck was Mal Moore’s nephew.”He didn’t know me from Adam,” Chuck told SDS. “I told him he might know my uncle, and he began to pick my brain about Mal and his career.”

Over time, Chuck and Saban developed both a business relationship and a friendship. They spent time together on the golf course, where Chuck loved to talk football with Saban, particularly about old coaches. “He told me he never knew Coach Bryant, never got to meet him, but he absolutely loved Coach Stallings,” Chuck said. “Coach Stallings was his favorite coach.”

Chuck was always impressed with Saban’s hands-on approach to building and the way he treated many of the laborers. “He’d get out in the yard and help them tote lumber,” Chuck recalled. “And he was interested in them individually. He treated each of them with respect.”

In Saban, Mal saw Bryant-like values. Through the years, Mal and Chuck had numerous conversations about Saban, and both believed if anyone could raze and rebuild Alabama back to greatness, it was Saban. So when Mal was looking for a new coach, he knew just who to call.

After Shula was fired, Mal immediately called his brother Frank, Chuck’s father. He needed a favor. “Mal called me and he said, ‘Frank I’ve made a decision to let Shula go and go after Saban,'” Frank told SDS. “‘I need all of Chuck’s numbers, because I’m going to use Chuck as a go-between.’”

Mal later communicated through Saban’s agent, Jimmy Sexton, but the discussions with Chuck were critical to the overall process. Mal relied on Chuck to “talk” to Saban via third-party communication, which included sending information on the Board of Trustees, President Witt, and the amenities in and around Tuscaloosa. “Mal called me and gave me strict instructions,” Chuck told SDS. “I couldn’t talk to anyone, even my dad. He would call me and have me call coach and talk to him about different things about Alabama.”

“When he had something important to say, Mal would send it through Chuck and Chuck would tell Saban,” Frank said.

For instance, since the Moores knew Saban was a “water man,” Mal sent information on Lake Tuscaloosa to Chuck, who then UPSed the package to Saban. Knee-jerk decisions were not a part of Saban’s lexicon, and if the end game was ultimately to take the Alabama job, a degree of due diligence was required.

Technically, Saban never spoke to Alabama directly until Day 36 of the search, the night of Jan. 2 when Mal Moore was in his living room.

Day 9

‘My heart sank’ … and a change of heart

On Sunday, Dec. 3, Mal Moore flew to New York to attend the National Football Foundation’s annual banquet at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. Everybody who is anybody in college football was invited, and Mal used this gala as an opportunity to vet a number of coaching candidates, including West Virginia’s Rich Rodriguez and Rutgers’ Greg Schiano. That week, Moore also met informally with Spurrier, who politely echoed his sentiments to remain in South Carolina. “He met with Spurrier and his wife,” Townsend told SDS. “He asked Spurrier if he was interested and he said no.”

Though Mal Moore had meetings scheduled with Rodriguez and Schiano, what evoked his keenest interest was a meeting with Jimmy Sexton scheduled for that Monday in New York, Day 7. Since everything was hush-hush, Moore’s team secured a private area of the hotel for the meetings, thereby eluding the scent of galling reporters. Even close-knit advisors such as Ronny Robertson were not fully apprised as to matters behind closed doors. “(Mal) called me between one of the meetings and said, ‘Listen, I’m interviewing. We need a bucket of ice,'” Robertson told SDS. “He didn’t even want a bellhop to come in.” Robertson never knew whom Moore was interviewing.

The Monday meeting with Sexton was not a full-blown discussion of contractual details, but rather a wade-in-the-water affair to see whether Saban might hup two for an interview. Moore produced photographs of the athletic facilities that showed significant upgrades to the near-Draconian facilities that dotted campus previous to his administration. Sexton gave his compliments, but kindly reiterated that Saban wasn’t going to talk to Mal until the final curtain of the Miami season was drawn.

Surely the fact that Sexton agreed to a meeting was evidence that Saban had some interest, but when Sexton later suggested that if Saban returned to college, Alabama was one of the schools on his short list, Moore’s hope was piqued. “Jimmy did inform that it was true that Nick had expressed he wasn’t overly enamored with the NFL,” Moore wrote in his book, Crimson Heart.

***

“But Mr. Huizenga, touted as one of the best owners in the NFL, was very persuasive. It was the new challenge, being head coach of a well-respected professional team and having so much control, as well as having a boss who was a smart businessman and a good person that tilted the balance of good sense. It probably wasn’t as different for Nick in the NFL as it was for me. Coaching is coaching … football is football … and while the draft is a long way from recruiting, it’s still all about knowing and identifying talent and balancing that with your team’s needs. And if it hadn’t been for the timing of a quarterback situation along with the opening at the University of Alabama, Nick could still be at the Miami Dolphins … and I would probably be taking more tennis lessons, more Bible study groups and book clubs, and learning to play bridge.”

– Terry Saban to SDS

The one takeaway from the meeting was a promise that Sexton would call by Wednesday, Day 9, at a set time to inform Mal if it was possible to speak to Saban after the Dolphins’ season. That briquette of hope was the best Moore could get.Before the banquet on Tuesday, Moore met with Rodriguez and Schiano in the private suite. Rodriguez, 43 at the time, and Schiano 40, were rising stars, both with 10-win campaigns for 2006. “I really thought we had productive meetings,” Moore wrote in Crimson Heart. “Both were interested in the job.”

Eight days into the search, Moore faced two options: Offer the job to a proven coach or wait four more grueling weeks to see if a more proven coach might speak to him, though there was no guarantee a deal could be struck. If Saban eventually said no, could he get a coach as good as Rodriguez or Schiano? Probably not, he surmised. If he waited another week, he might lose Rodriguez and Schiano. These were the roving hypotheticals that tossed in his mind.

Perhaps that pressure reached a boiling point on Wednesday, Day 9. Decisions were made that would have led to future “What if?” scenarios. Sexton had promised to call by an allotted time, and Mal, waiting nervously for his call, was crestfallen as the time came and went. Receiving this as a “no,” Mal immediately phoned Rodriguez and offered him the job. Rodriguez accepted, and a meeting with his agent was scheduled the next day at Mal’s home in Tuscaloosa.

Mere minutes after the offer, Mal’s phone rang. It was Sexton, who informed him that his flight had been delayed and he had been stuck somewhere in the hard skies with no cell phone coverage. “My heart sank,” Moore admitted in Crimson Heart.

Mal Moore left New York on Day 9 believing Rich Rodriguez was set to be the next coach at the University of Alabama.

The next day, Thursday, Dec. 7, officials in Alabama’s Rose Administration Building scrambled to draw up the Rodriguez paperwork. Later that day, Moore received a knock on the door of his Tuscaloosa home. One of his “insiders” was ready to traffic significant information: Rodriguez was staying at West Virginia. This might not have been as awkward had Rodriguez’s agent not have been inside the house.

“How reliable is this information?” Moore asked from his front stoop.

“Impeccable,” the source said.

That source was Steve Townsend.

To the delight of the Mountaineer faithful, Rodriguez later held a press conference announcing his plans to remain at WVU. Moore, turned down for the dance, embarrassingly released a statement. “I fully respect his decision and wish him the best,” he wrote. “I want to remind everyone of what I said at the outset of this process: my only objective is to get the best person available to lead the Alabama football program. I remain determined to bring to our program a proven head coach with impressive credentials.”

***

What happened over the course of those 24 hours is up for dispute, and to this day, the real reason RichRod cold-shouldered Alabama is muddled. With egg on his face after Rodriguez’s stiff-arm, Moore had to deal with the ungallant reality of offering the job to a second choice. The vice-grips were tightening and the weeping and gnashing of teeth were feared.

But privately Moore was relieved. He didn’t want to hire the upstart lounge singer to perform at his theater of football. He wanted Elvis.

Loping into winter now, Mal began to perceive pressure — whether founded or unfounded — from the Alabama administration and the board of trustees to secure a coach. “I don’t think he necessarily got a phone call,” Robertson told SDS, “but as conscientious as he was, he channeled that into, ‘If I don’t hire a coach, the president and trustees are going to have my neck.'”

Recruiting for the upcoming season was another consideration, and the longer the process took, the greater chances that prize recruits would defect.

Moore didn’t have much else to rely on than gut feeling (those trusty instincts had eluded him in the past) and suffice it to say that his inclination to go after Saban full-bore stemmed largely from the conversations Chuck had had with the Dolphins’ coach.

“My feeling on it from my conversations with (Saban) was that might be interested in the job,” Chuck told SDS. “With Mal being an old football background A.D, it could be what he was looking for. My feeling was that Mal needed to stay after him.”

That he did. On Friday, Day 11, Moore boldly called all hands on deck, scheduling a secret meeting of his secret team at his very public house. Now there was no turning back.

That night, a bitterly cold evening, team members were instructed to park blocks away so as to not call attention to the covert congress.

One of the main topics of discussion that evening was financing. One team member procured a list of comparable salaries for head coaches; included was the pricey salary of Oklahoma’s Bob Stoops. Running numbers, Moore concluded that, even though Saban was making north of $5 million with the Dolphins and would have to take a pay cut, $4 million would be an attractive offer.

During the night, an unexpected visit from a couple of Moore’s lieutenant ADs furnished a comedic break. Because Moore was determined to preserve the identities of his inside team, he hustled them into a laundry room before meeting with his colleagues in another part of the house. “We had a good laugh when they joked about inhaling all the detergent fumes in there,” Moore wrote in Crimson Heart.

Closing the wide gulf between Shula’s salary ($1.55 million) and Saban’s offer would be accomplished only with the help of school president Dr. Robert Witt and Paul Bryant Jr. Ultimately, these were the two men who could give the nod to such towering coin.

“Dr. Witt deserves credit,” Townsend told SDS. “He had the foresight to understand economics. He and Paul Jr. were the ones who got that consummated.”

Financing behind them, Moore had to figure out how to get to Saban. While Saban was negotiating a brutal December schedule that included the Patriots on Dec. 10 and the Jets on Christmas Day, Moore used the only two outlets at his disposal to get the carrot in front of the hare: Jimmy Sexton and his nephew Chuck.

Day 24

‘I’m not going to be Alabama’s coach’

The week of Dec. 11, Moore met with Sexton in Tuscaloosa, the festivities so secretive that Sexton had to park his car indiscreetly at a shopping center in Northport before being shuttled to Moore’s house. This meeting was more substantive than the initial meeting in New York, such that Moore wondered at the conclusion of the meeting if the parties had a deal. “Mal, this is a deal contingent on Nick Saban deciding to meet with you,” Mal wrote that he recalled Sexton saying.

A quiet but anxious ether hovered over the next 10 days. During this time, Moore continued to interview candidates, including coach David Cutcliffe, Tennessee’s offensive coordinator, in Birmingham. “He talked to Cutcliffe a long time,” Robertson told SDS. “An hour-and-a-half conversation. Mal was very impressed with him.”

Half a world away, the Dolphins suffered a 21-0 loss at Buffalo on Dec. 17. The Dolphins sat at 6-9, out of playoff contention for the second consecutive year.

That week, as rumors and innuendo continued to swirl and curiosity of the press grew unrelenting, Saban broke. At a Thursday, Dec. 21 press conference — Day 24 — Saban huffed, “I guess I have to say it. I’m not going to be the Alabama coach.”

This gauntlet utterance would later be the cause of Saban’s vilification by the Dolphins’ coterie — many of whom, to this day, remain pitiless and unforgiving.

“I don’t think Saban was lying when he said he wasn’t going to Alabama,” Townsend told SDS. “I think he meant it at the time.”

On Monday Night Football, held on Christmas night, Saban gazed into a half-full Dolphin Stadium. During the game telecast, legendary coach Don Shula, Mike’s father, bristled at Alabama, suggesting they need to “evaluate the evaluators.” (Perhaps he would have never guessed that Alabama’s eventual replacement was patrolling the ‘Fins’ sideline that night.)

While Alabama prepped for Shreveport, Moore flew to Houston to meet with Mike Sherman, associate head coach for the Houston Texans. Moore came away impressed but no offer was extended.

On Dec. 28, Kines, wearing crimson garb that mirrored Shula’s usual Paddington Bear get-up, did the best he could (and gave a pulsating halftime interview for the ages), but Alabama fell to the Cowboys 34-31. With that pedestrian 6-7 season in the books, Moore could now spend the rest of the holiday season without the pesky interference of a game.

Thirty-one days after firing Shula, Moore still hadn’t found his replacement.

Moore rode back to Alabama with Steve Townsend, and together across three states the pair prepped for an upcoming trip to the Sunshine State to meet Nick Saban. Moore had booked a flight to Miami on Jan. 1 and the two men discussed myriad details of the excursion while in the car.

Because plane rides of SEC coaches seem to fascinate the press, Moore decided to fly on a private plane owned by personal friend Farid Rafiee. Ironically, the pilot was Bud Darby, former Alabama quarterback Richard Todd’s brother-in-law. Though no one would verbalize it, the flight carried a heavy weight in the instructions, “Don’t come home without him,” harkening back to a Siamese directive aimed at then-Alabama assistant coach Howard Schnellenberger, who, on a long-ago trip to Beaver Falls, Pa., was responsible for snagging a young, cocksure quarterback named Joe Namath.

Day 36

‘I’m taking this plane to Cuba if Nick Saban isn’t on it’

The weather was inclement as Mal Moore’s plane took flight that Monday. Landing in Miami, he hooked up with a driver named Francisco “Frankie” Rengifo, who zipped him around in a Mercedes sedan. Mal checked in to a hotel that was a block from Saban’s Fort Lauderdale house and for the next two days, went back and forth with the members of his team who were in constant contact with Terry Saban and Jimmy Sexton.

Everything was in a holding pattern until a member (any member) of the Saban family allowed Mal — who was doing everything in his power to get his foot in the door — access to their lives.

At one point on Tuesday, the weary athletic director almost gave up and came home. Moore checked out of the hotel. Robertson recalled their conversation. “Mal called me and said, ‘Gah! You won’t believe it,'” Robertson told SDS. “‘I’ve been sitting out there in front of this gate by his house. I’ve been camped out here for a day and a half.”

“How’s it going?” Robertson asked.

“Hell, I don’t know,” Robertson recalled Mal saying. “I talked to his wife, and I can tell she really wants to come to Alabama. I haven’t seen Coach Saban yet. I’ve already checked out of the hotel. Now I gotta figure out where I’m going to stay tonight.”

At some point Tuesday, Moore also talked to Sexton. According to an article by ESPN’s Mark Schlabach, their conversation went like this:

“Jimmy, we’ve been talking about this for a month,” Moore said. “He won’t even meet with me. We’ve got to make this happen.”

“Mal, just be patient with him,” Sexton said. “You’ve got to hang in there. Do not get on that plane and go back to Tuscaloosa.”

“Don’t worry,” Moore said. “I’m taking this plane to Cuba if Nick Saban isn’t on it.”

But something within him, something fierce, a seed of determination that was planted long ago in Dozier, Ala., that sprouted as a backup quarterback under Bear Bryant, that blossomed as an assistant coach and grew to full stature as an athletic director, kept him there that day. Instead of returning from the front lines with his tail between his legs, the old soldier made one last run.

Finally, after waiting outside the gates of Oz for nearly two days, Terry Saban buzzed him in. Mal, the frosty-haired, seasoned recruiter, put on his best sell as he and Terry chatted over lunch. “I like to think that she and I hit it off that day,” Mal wrote in Crimson Heart. “At least that’s the way I remember it.”

But Nick Saban was nowhere to be found. Terry informed Mal over lunch that her husband was at the Dolphins’ office, conducting his annual year-end meeting with the players. Terry invited Mal back for dinner later that night.

That afternoon, Saban phoned his wife to tell her that he was staying with the Dolphins. But after Terry insisted that he at least meet with Mal, Saban finally relented.

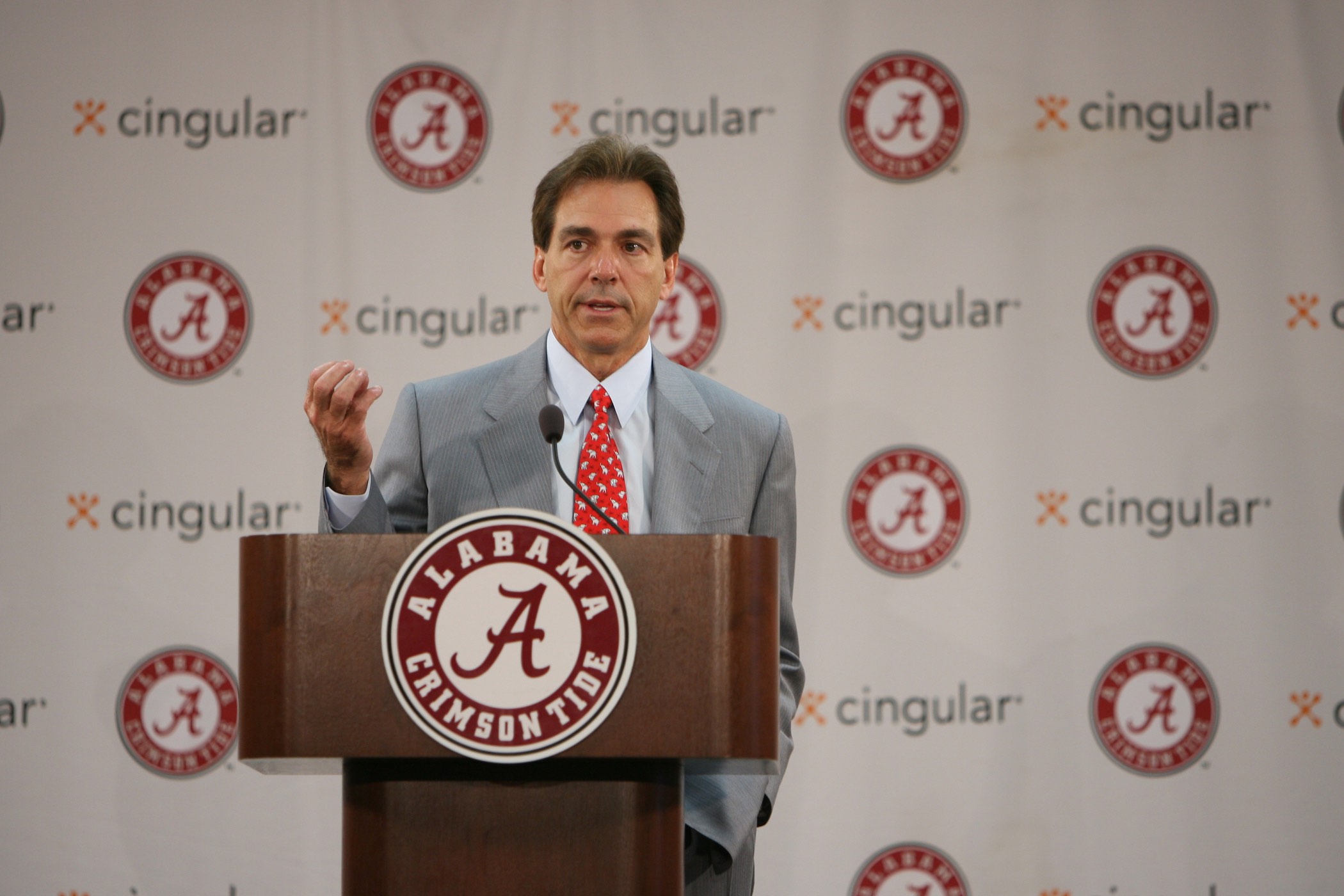

That Tuesday night — Day 36 — the Sabans gathered in their living room with Mal Moore. Bundling his decades of recruiting savvy into one terrific recruiting spiel, Mal convinced Nick Saban to leave his superlative gig with the Dolphins and come to Alabama.

And although the exact details of that conversation will never be revealed, Terry Saban provided a bit of insight to the personal qualities and potent words of Moore that signaled the tipping point.

“It was Mal Moore’s soft approach, fatherly advice, sweet Southern charm … ‘I’m here for you … come back home … back to where you belong … you are a college coach … we need each other …’ His siren songs were in my ears and I made sure Nick heard them. The three of us stood in our living room in tears, acknowledging that our hearts were still in college and that there was not a number that Wayne could throw out to us that would make us reconsider what was the best thing for our family, not double, not triple. It was never about that.”

-Terry Saban to SDS

But Huizenga was an old soldier, too. On Wednesday morning, Huizenga met with the Sabans in the same living room Mal Moore had been in the evening previous. There were no discussions about money or contract extensions, but rather what was in Saban’s heart. Saban respected his owner so much that he needed his blessing. That morning, Huizenga gave it.

Shortly thereafter, an emotional Saban phoned the Dolphins’ complex and informed his coaching staff via conference call that he would not be returning. Huizenga called a press conference later that day, and reporters jammed into a small room at the Dolphins Training Facility. Clad in a designer suit and salmon tie, Huizenga made Saban’s departure official.

“Well as you know, Nick Saban has decided not to return to the Dolphins,” Huizenga began. “It is what it is.”

Reporters took the liberty of lobbing a few mortars. “Are you upset about the way Nick Saban handled this over the last couple of weeks?” one reporter asked.

“The answer is no, I’m not upset,” Huizenga said. “Because it’s more involved than what you think … I feel the pain of Nick and Terry and it’s not a very simple thing.”

“After this guy lied to the media, gave you a different impression, lied to his players, why would you want him back?” fired another reporter.

***

“Surely the Dolphins fans would understand that it was not the right fit for Nick or for them? After all, the media there was not very kind to Nick and his organized process, so they might even be happy about it, right? Wrong. I was a little taken aback by their attack, even when in the end, Wayne got it.”

-Terry Saban to SDS

By the time Huizenga approached the podium, the Sabans, in the middle of their own hegira, were already furiously packing their belongings to board the plane to Alabama. By then, the news of Saban’s departure had spread throughout the country, and as the Miami press hovered like ravenous buzzards around Saban’s home, helicopters swarming overhead, a contingent that included the Saban family plus Mal Moore was piling into the Mercedes. “They crammed luggage everywhere,” Townsend told SDS. “Mal rode on the gear shift box. Saban by the window. Terry and the daughter and her friend in the back seats.”Inside the car, Mal phoned Chuck with the terrific news. “We got him!” Mal exclaimed.

Day 38

A hero’s welcome

Hearing those words, an exultant Chuck felt both supreme joy and a sense of relief. This overlong saga was now just over. “My Number 1 thought was that he’s got a man now who knows what it takes to build a program and that it’s going to make my uncle’s job much more pleasant,” Chuck told SDS. “I also felt the same way for coach. They should work well together. I felt good for both of them.”

Mal also called Ronny Robertson to set up the logistics of transporting Saban from the airport in Tuscaloosa to Bryant Hall, where he and Terry would be staying until they found something more permanent.

“And while there will always be regrets for not having finished the way we like to, we could not turn our backs on Coach Moore and the opportunity he presented to us that may never come along again, the challenge we both loved, to turn around a college program rich in tradition and history, to get back to our roots where we both fit more comfortably, and to do it with a great fan base and a father-like figure in Mal Moore, who understood the challenges of building a program and was willing to give Nick what he needed within the structure to make it work. Mal trusted Nick that he had the rest of what it took to make it happen … the work ethic, the football knowledge, the solid base of values on which to build a program without cutting corners.”

-Terry Saban to SDS

When the plane touched tarmac in Alabama, the airport fences were lined with throngs of adoring fans that ran the gamut of the social ladder. “Praise the Lord, God is so good, Nick is now in the Bama hood!” quoth Collete Connell in sort of a rube-like poetry. (Connell was the fan who infamously planted a kiss on Saban’s cheek.)

Saban, smiling broadly and signing memorabilia, inched forward as the crowd of crimson-swathed fans belted a Southern chorus of “Woooo! Woooo!” The length of a football field away, a fleet of automobiles was waiting to whisk Saban and his entourage to Bryant Hall. Saban climbed into the back of a crimson GMC Yukon driven by Ronny Robertson as fans produced digital cameras to capture the moment.

“I picked him up,” Robertson told SDS. “I had an SUV with John Gilbert, who was the assistant AD. It was a zoo out there.”

Following a police escort, Robertson nosed through the congested city of Northport as he and Gilbert explained the particulars of Saban’s first night in Tuscaloosa.

One of Saban’s first phone calls from inside the SUV was to Chuck. On the plane ride, Mal had informed Saban that Frank was also a good golfer, and Saban used this as an opening for some lighthearted needling. “Coach called me and said, ‘You talk about how good a golfer you are; you can’t even beat your dad,'” Chuck told SDS. “I said, ‘Well I tell you what, you play him!'”

After arriving at Bryant Hall, Robertson and Gilbert showed the Sabans their temporary accommodations. Saban had one request.

“Saban said, ‘Is there a coffee maker here?'” Robertson said. “And John and I started jumping through hoops. We went into an efficiency kitchen in Bryant suites and began opening cabinets and found it. I made coffee. I remember I took it back in there to him.

“I said, ‘Coach, do you need cream and sugar?’ He said, ‘I don’t want coffee now. I just wanted to make sure I got it in the morning.’ John and I looked at each other and thought, ‘Boy, we blew that one!’”

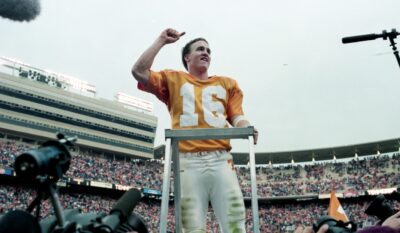

On Thursday, Jan. 4, 2007 — 38 days after Moore fired Shula — Saban took to the podium as the 27th head coach in Alabama football history, setting in motion an unprecedented decade of dominance.

“So in the past 10 years in Tuscaloosa, we have never looked back, and based on Nick’s philosophy, we rarely look very far beyond the present day. Rather, we immerse ourselves in what we need to do in a disciplined, orderly, and spirited fashion. Nick continues to be motivated by his players … it’s all about the players he often says. Yes, it’s nice to win, but it’s more about helping these young men be winners … in life, in everything they do.”

-Terry Saban to SDS

Postscript

It seemed that the stars perfectly aligned for Saban to come to Alabama. It was a Series of Fortunate Events. But for just a moment, consider:

What if Dennis Franchione hadn’t jumped ship for Texas A&M in 2002?

What if Mike Price hadn’t bungled his opportunity as the coach at Alabama?

What if Tim Tebow had signed with Alabama and not Florida?

What if Saban had signed Drew Brees and not Daunte Culpepper as a free agent in the spring of 2005?

What if Mike Shula had beaten Mississippi State and Auburn in 2006?

What if Rich Rodriguez had stayed true to his verbal agreement?

In procuring Saban, Alabama pulled off a football heist of Lufthansa proportions. And even the most spoiled of Alabama fans would have to admit that what Saban has done over the past decade has exceeded the hardiest of expectations.

“I think Mal’s personality, his background in football and coaching, these were his defining personality characteristics that helped sell Saban,” Townsend told SDS. “Saban developed great trust in Mal.”

If the volta of Alabama football had more to do with the qualities Saban valued in Mal Moore, an important question about Mal’s legacy must be posited: “With the hiring of Saban, has Mal Moore received atonement for the miserable and excruciating pre-Saban years as AD?” History has often been hard on him, but perhaps one great defining triumph should cover a multitude of demerits.

But life is often sadly poetic, and the old soldier’s crimson heart stopped beating on March 30, 2013. By then, Mal had been involved, in some capacity, with 10 Alabama national championships. All 10 fingers of the hands that once were dipped in the loam soil of south Alabama now had rings for them.

Reflecting on his friend, Saban described Mal as the most selfless man he’d ever known. “My happiest moment for Mal was when he won the John Toner Award, given annually to the nation’s best athletic director,” Saban wrote in Crimson Heart. “I saw him before the dinner, and he had tears in his eyes and he thanked me for changing his life. I told Mal that he had it wrong. Mal Moore had changed my life.”

It can be said that 38 days is as much a story about the persistence, tenacity, grit, humility and wisdom of Mal Moore as it is the hiring of Nick Saban. That the former backup quarterback who paid his dues and just kept plodding and plodding, even as he was passed over twice — once as a player, once as a coach — finally had his day.

In the end, Alabama didn’t have just a legacy and nothing else to sell. It had something that was very unique to the University. It had Mal Moore.

“So here we are in a hotel room in Atlanta. It’s been two weeks of preparations for the big Final Four game this Saturday, and the weather channel showed 6:30 a.m. … “Gotta go!”

-Terry Saban to SDS

Al Blanton is a lawyer and former college basketball coach who discovered a passion for writing. In addition to freelance writing, Al is the owner of 78 Magazine, based out of Jasper, Alabama.

Photos from University of Alabama

Al Blanton is the owner of Blanton Media Group, publishers of 78 Magazine and Hall & Arena.