Small-town Alabama to the Big Dance, Purdue’s Isaac Haas isn’t ready to give up the fight

By Al Blanton

Published:

Isaac Haas was a big deal in Alabama high school hoops. And he was doing even bigger things for Purdue, until he broke his elbow in the NCAA Tournament opener. The 7-2 center they call Ivan Drago is down, but he refuses to be counted out.

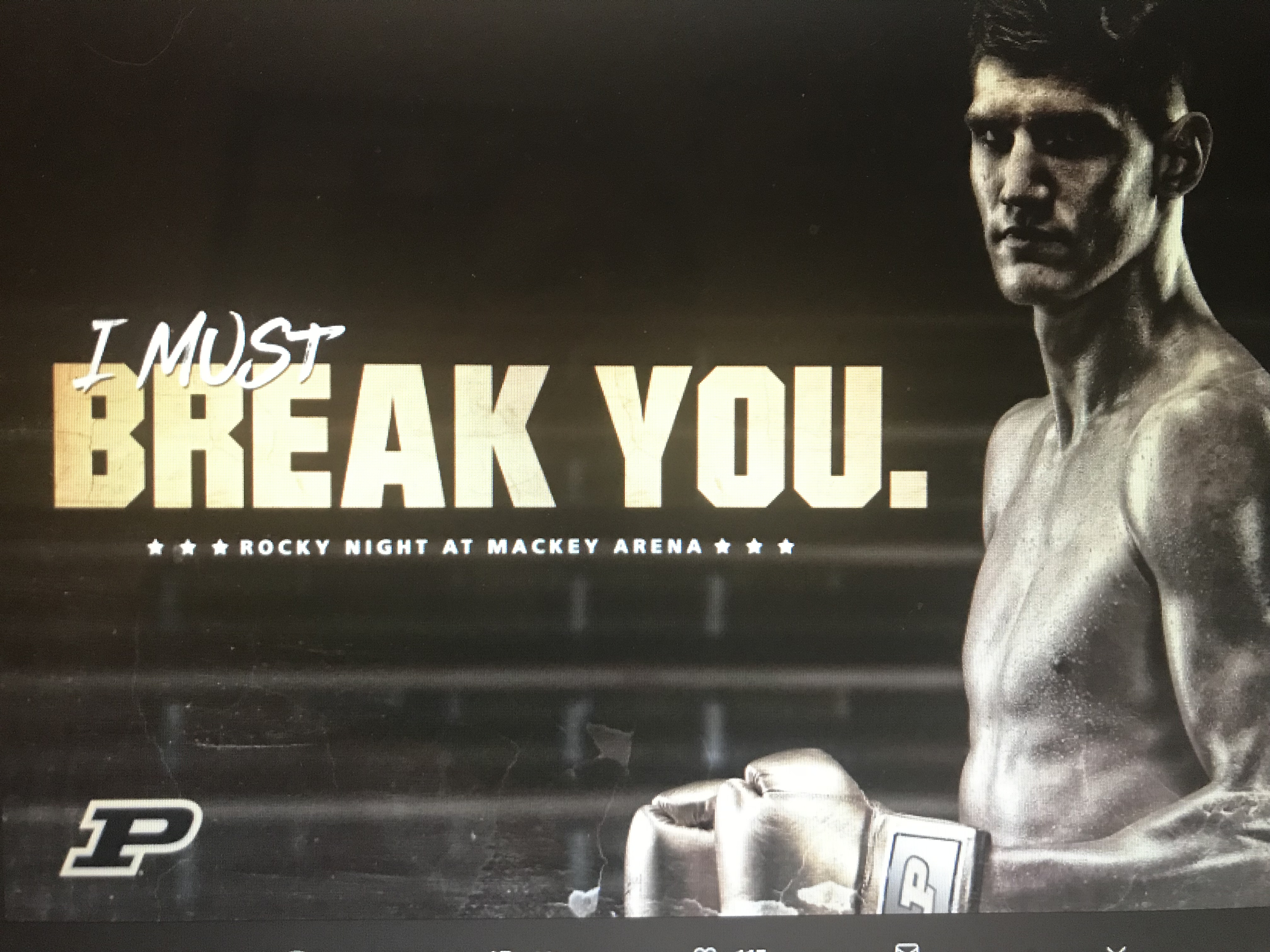

On Jan. 31 on a Hoosiers-cold Indiana night, Purdue basketball hosted “Rocky Night” at Mackey Arena. As a promotional for the event, the athletic marketing department designed several posters, the cleverest of which involved the Boilermakers’ 7-foot-2 center, Isaac Haas. Haas, who favors the Russian foil Ivan Drago in the movie Rocky IV, is shirtless and sweat-slick, gold boxing gloves covering his large mitts. As Drago — er Haas — stares menacingly into the camera, beside him, the caption reads, “I MUST BREAK YOU.”

This Friday, Haas learned firsthand about unfortunate breaks. During the second half of Purdue’s game versus Cal State Fullerton, Haas cracked his elbow when he tumbled to the floor. As Purdue Nation let out a gut-wrenching sigh, the initial response from media row was portentous. “To me, it kills their season,” said CBS commentator Charles Barkley. Clark Kellogg described the injury as “devastating.”

But if anyone knows Haas, or Purdue for that matter, this knock-down will not mean a knock out. On the official Purdue Men’s Basketball Instagram page @boilerball, a picture of Haas was captioned, “We now have the nation’s biggest cheerleader … He will be there for us … you know we will have his back #boilerup #marchmadness.”

Now CBS is reporting that Haas is going to wrap his elbow up and — Great Scott! — try to play in Sunday’s second round matchup against in-state rival Butler. With such resiliency and durability, spectators are left with one question:

Could Haas actually be Ivan Drago?

*****

Purdue’s unlikely romance with Haas began four years ago when coach Matt Painter forged deep into the South and plucked Haas from a small community in Alabama called Hokes Bluff, an hour northeast of Birmingham. Actually the Haases live just outside of a community called “Ballplay,” named after a creek and somewhere between the tiny towns of Hokes Bluff and Piedmont. All of that is hard to explain, so Haas’ mother, Rachel, simply says “Hokes Bluff” when asked where the family lives.

By no means a metropolis, Hokes Bluff is a town measured by four-way stops. Some folks insist there’s only one in town, others may lobby for two or three. The epicenter of action occurs at a five-and-dime called Cash Saver Foods, the local hangout for teenagers. It’s clear that there’s not much to do, that time draws out deliberately, and it’s a really, really big deal when a 7-foot local appears on ESPN.

Greg Watkins, Haas’ high school coach, describes his former player as a “regular kid,” a once-goofy, happy-go-lucky high schooler whose maturation process over the past four years at Purdue has been remarkable to watch. “He was just like every other kid, but he’s a 7-footer,” said Watkins. “He’d forget shoes at practice just like everybody else.”

In ninth grade, Haas was already standing at 6-10 and Watkins could tell that he had potential. The only question was how high. In practice, Haas was easily tired and often slumped over after a grueling session beneath backboards. Watkins soon questioned the trainer, who informed him that Haas’ back muscles had not developed to support such a large trunk. Such is the life of a 15-year-old burdened with altitude.

Rachel says that Isaac’s unusual height was no surprise. When Isaac was 2 years old, he was already 3-5 and could reach the light switch in their diminutive apartment in nearby Jacksonville. “It used to drive us crazy,” Rachel remembers. “We would tape the light switch. But he was happy and good-natured. He wasn’t trying to be sneaky. Eventually we started taking the bulb out.”

As the years went by, the family had to find ways to accommodate Isaac’s unique set of circumstances. His world was one of oversized shoes, XLT clothes, and vaulted ceilings. “We wanted to make it where Isaac could stand up and not get his head chopped by a ceiling fan,” said Isaac’s dad, Danny Haas, who works as a police officer in the city of Gadsden.

But Isaac’s inconveniences were small compared to his sister, Erin, four years his younger, who has battled epileptic seizures her entire life. And instead of taking on the typical role of nagging older brother, Isaac demonstrated compassion toward his sibling. “He became like a third caregiver for her,” Rachel said. “I’ve always called him a Mother Hen. For him, it was watching her constantly out of the corner of his eye to make sure she’s OK at all times.”

There was a point in Isaac’s development where basketball wasn’t a certainty. He grew up excelling at both football and basketball. At one point, Rachel thought he might play college football, as coaches from SEC football schools were already showing up at practice. “He’s a ridiculously strong person,” she said. “He played some O-line, and they were moving him permanently to tight end his eleventh grade year. But people would get underneath him and cut block him.”

During spring training though, Isaac was faced with a decision that would test his character. He had linked up with an AAU basketball team out of south Alabama, but football obligations would prevent him from summer workouts. “The coach was willing to work with him. He said, ‘Don’t worry, he’ll be a starter,’” Rachel said.

But Isaac didn’t feel right about it. “He said, ‘Mom, it’s not right for me to miss and somebody else be there and me play,” Rachel recalls.

Instead, Isaac decided to quit football and concentrate on basketball.

Watkins was always impressed with Isaac’s work ethic, and that he didn’t take his size for granted. “If you’re bigger than everybody else, sometimes they feel like they don’t have to work hard,” Watkins said. “Isaac was never that way. Anytime he had spare time, he wanted to be in the gym.”

And behind his relaxed portico of personality, something savage, something blazing, resided within. Call it grit, call it perseverance, call it what you want. Isaac Haas — unlike other colossuses that come down the pike — had what it took to make a Division I athlete.

Whispers of Isaac’s exploits were soon passed around at diners from Gaston to Sandrock. “Have you seen the big 7-footer at Hokes Bluff?” curious fans would ask. Gyms were packed to overflow.

“It was a big draw,” Watkins said. “We’d have a big turnout wherever we went.”

As graduation neared and recruiters began to hover around Hokes Bluff, Isaac felt he needed a buffer. Enter Rachel.

Now, Rachel is what Southerners would call a “pistol.” She gives off a bit of a Leigh Anne Tuohy verve: She’s super-knowledgeable about the game of basketball (describing her preference for the inside-out game, she says that a low post presence can open the door for drives to the basket and pick-and-pops), she is both protective and proud of her son, and something tells you you don’t want to get on her bad side. But behind this façade, Rachel has a terrific laugh. It’s the kind of delightful giggle that a girl might give after she backs up from a high school kiss.

During Isaac’s college recruiting process, Rachel was in charge of the initial vetting of schools. “It was extreme, too,” she says. “(Isaac) wanted me to narrow down people based on my feelings about it from talking to them. And then once they got through several levels with me, then he would start talking to them.”

Somewhere along the line, Rachel suggested Purdue — “Purdue?” Isaac inquired. “Where’s that?”

“It’s up in northern Indiana,” Rachel said.

But Rachel had done her homework. She was impressed with Matt Painter’s philosophy on bigs. She knew he wasn’t BS-ing her like other coaches were when he said his teams play inside-out. She researched the school and discovered a commitment to education.

Elite big men play at #Purdue.

?? 3rd straight year a Boilermaker has been a finalist for a big man award. #BoilerUp pic.twitter.com/EQi2zQOLze

— Purdue Men's Basketball (@BoilerBall) March 9, 2018

Isaac considered UAB and Wake Forest (the big state schools — Alabama and Auburn — were never really a good fit for Drago), but in the end the boy with size 22 shoes from Hokes Bluff chose West Lafayette, Indiana, for his college years. “The fact that they put so many big men in the NBA (was important),” Haas told The Gadsden Times on signing day.

Haas arrived at Purdue gangly and unrefined. Though Watkins and Jeff Noah, an assistant at Hokes Bluff, worked with him to develop his basketball skills, particularly his low post portfolio, Haas didn’t comprehend what it took to succeed at the Big Ten level. But that is precisely why Haas signed with Purdue in the first place.

Painter held his promise. Through an incredible strength and conditioning program led by Josh Bonhotal, a veteran of the Chicago Bulls’ strength program, Haas chiseled into a space eater who wreaked havoc in Midwest lanes.

He’s gotten tougher, too. Training under Painter engenders thoughts of a barn in the Siberian wilderness. No easy way out. Hearts on fire, strong desire. Rachel describes Painter’s practices are a “free for all.” “Their practices are ridiculous,” she laughs. “There’s no such thing as out-of-bounds or a foul. It’s a brawl. I can’t even watch it. I just stay at home. I’ll just be here, cooking something.”

Across four years, Isaac’s numbers steadily improved. In 2014-15, he started 11 games and averaged 7.6 points per game in only 14 minutes of action. This season, he averaged 14.9 ppg in 23 minutes of action. He was also was second in the Big Ten with a .617 field goal percentage, and in January he had back-to-back-to-back 20 point games.

Under Painter, Purdue’s program has been elevated to one of the elites of the Big Ten. For the past three seasons, the Boilermakers have won at least 26 games, reaching the high water mark of 29 this season with Butler standing in the way of 30. Mackey Arena, one of the loudest in the country, is always packed to the gills with yawping fans in their black T-shirts and gold-painted pots.

Purdue’s rise to the top of the conference can be attributed largely to the development and presence of Haas, though he’s had to endure certain criticism from the politburo. Opposing fans have been particularly unkind, and one article suggested that one way to stop Purdue is to let Haas get his and limit the other four players. Haas seems to take these pokings with class, floating along like a mallard in a pond.

Back in Hokes Bluff, there’s still a lot of interest and water cooler talk about Isaac. “I know there’s a lot of people in Hokes Bluff that had to subscribe to the Big Ten Network,” Watkins says. “I kidded their coaches one time. I said, ‘Hokes Bluff is probably leading the Big Ten subscription in Alabama, ’cause everybody here got it to watch him play.’”

Seeing her son on TV and his image on posters is something that Rachel hasn’t gotten used to. She’s proud of the man he’s become, and to her he’s still the boy with the “pick someone else up” mentality. “If you watch any video, if someone’s on the ground, he’s picking them up,” says Rachel. “The other team, his team, he’ll pick them up, set them on their feet.”

From time to time, Rachel and her husband, Danny, will drive up to a game. They were in attendance on senior night when Isaac thanked the West Lafayette community for raising money for Erin. Before the game, Isaac had been concerned that he hadn’t properly thanked everyone for their support, and Rachel, exhibiting her Southern succor, told her son, “Honey, you’ll have your chance to let those people know what they mean to us.”

And when the benevolent giant took the microphone in front of a hushed Mackey Arena, he broke down and cried.

This past Thursday, Rachel, unaware that her son would break his elbow, was packing her bags for a long drive to Detroit with her family. Excitement about the prospects of the NCAA tournament filled her mind and her voice. Could Purdue potentially make a run? Is this the year? were thoughts tossing through her head. Now Rachel must watch as her son humbly takes on the role of senior/leader/cheerleader for a Boilermaker team sans their best player.

*****

Haas’ success and subsequent injury has a few pundits scratching their heads. Because of the diminished role of the center in the modern day game, players like Haas have become an anomaly. The rare occurrence of a center present questions, not only for opposing teams, but for officials as well. If a big body is getting hammered all the time, how often do you blow the whistle? IndyStar writer Gregg Doyel wrote a compelling piece about the brutality administered to Isaac during the Cal State Fullerton game.

Doyel had a bird’s-eye seat at Little Caeser’s Arena for the first-round matchup and was taken aback by the “egregious” physicality of the game. “It was like watching a bunch of tiny villagers torment a grizzly. How long before the grizzly hurts someone? Turns out, that was the wrong question. The right question: How long before someone hurts the grizzly?” Doyel wrote.

If anyone felt the anguish of Haas’ injury, it was the Purdue family and the citizens of Hokes Bluff. Watkins is now retired from basketball and serves as a middle school principal. He says he keeps up with Isaac, sends him text messages after a big game. When Isaac went down with his injury, Watkins described it as a “kick in the stomach.”

As Patti LaBelle once sang, this wasn’t how it was supposed to end.

For Isaac, four years seem to have flown by faster than a Lamborghini montage. This spring, he will complete four splendid years at Purdue. He’ll be eligible for the NBA Draft in June. The sky’s the limit for Isaac, and only time will tell whether his elbow heals and he makes it in the NBA, or if he puts his marketing degree to good use. Only time will tell if life in the Midwest has rubbed off on him to the extent that he wants to stay, or if he’ll return to his roots.

One thing is true from examining the life and determination of Isaac Haas of Hokes Bluff:

Nothing will break him.

Cover photo: Purdue Basketball via Twitter (@BoilerBall)

Al Blanton is a freelance writer for Saturday Down South. Follow him on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter @hallandarena.

Al Blanton is the owner of Blanton Media Group, publishers of 78 Magazine and Hall & Arena.