How Phil Steele became the undisputed king of the college football preview game

By Jon Gold

Published:

Phil Steele didn’t play football. He didn’t write, either. So how did he become the most influential source of college football information in the country? He made his magazine his life.

These are the final few days of fun, of summer, of freedom, of anything but football.

It’s been absolute torture for Phil Steele, really.

His ubiquitous magazine – referred to as “The Bible” by many college football fanatics – has been put to bed for months now. Christmas in June, they call it. The real start of the college football season.

He’s been on ice for weeks, his staff carousing across the country on vacations, the only football on television in the form of classic replays. It’s all been so … boring.

What’s about to come is what gets Steele up in the morning. Football is back, and there are about to be a dozen televisions with a steady glow just sitting there with his name on it.

And speaking of his name on it: That’s the best part of what’s about to come. Forget the touchdowns and the cheerleaders and the pompoms and circumstance.

Pretty soon, Phil Steele gets to find out if he’s right. And that’s all that matters.

* * * * *

It’s a little absurd, if you think about it.

Seven months – more than 30 weeks – dedicated to 352 pages of a printed magazine.

Granted, it’s the most thorough college football preview magazine in the country. Maybe the most thorough magazine about anything in the country. It is the go-to source for media and fans alike, the comprehensive guide college football enthusiasts use to shape opinions and fan their preseason optimism.

But this is life for Phil Steele. Life in 352 pages.

“Phil is like the most unique character I’ve met in football, and I say that in a good way,” said Mark Wolpert, Executive Director of the Maxwell Football Club. “He’s so passionate about what he does, and he goes so far down the rabbit hole. He makes me laugh sometimes – he’s like a mad scientist with it.”

He started tinkering early.

He was born in December 1960 into a blue-collar family in Cleveland. Dad, Henry, worked for East Oil Gas Co. after serving as a Sergeant in the Korean War; mom, Mary, was a secretary at the local Cadillac plant. Back then, the Browns were the preeminent franchise in professional football and Steele was hooked early. He remembers the 1964 NFL Championship game vividly. He was barely 4 years old.

Football cards were his thing; to this day, if you show him a Topps card from that era, he can tell you if he had it or needed it. With an older brother by 18 months, the mad dash to the morning’s newspaper became an Oklahoma Drill. Whoever laid claim first got the sports section for 10 minutes.

In the 4th grade, Steele did his first book report on a football player. Then his second. His teacher told him to pick a different topic. He picked a baseball player.

“She said, ‘No, something not sports.’ I said, ‘What is not sports?’” he said.

By the age of 7, he was a college football fanatic. He loved the Michigan helmets, even if his loyalties were to the Ohio State Buckeyes.

“The Buckeyes were huge for me,” he said. “I needed OSU to beat Michigan.”

Especially if he had them on a parlay card.

He’d started playing the parlays when his uncle brought over cards when he was 10 years old – $1 bets that paid out $5 for picking three correct winning teams out of 36 games, $10 for picking four and $20 for picking five. College and pro games, spreads typically at three or seven points, ties lose. When he was 12 or 13 years old, he had an eight-teamer come in, and he was hooked. Despite lacking playing experience himself — his football playing was relegated to backyard games with friends and he was too small to play high school ball in football-obsessed Ohio — he developed an acumen for the sport.

“It was my fascination,” he said, remembering one ticket specifically from 1979. He went bold on a 10-team card – the jackpot would’ve been a down payment on a car in those days – and he hit the first nine. “The only one I needed was Dallas to beat San Francisco, and San Francisco had been a crappy team for years, and they had this new quarterback, Joe something, his first year starting. They’re 3-0, and I say, ‘They’re not a 3-0 team, not with a rookie QB.’ I was pretty comfortable. But the Joe was Joe Montana.”

Two years later, idle after spending a couple of quarters at Cleveland Community College and managing a restaurant, Steele made his big play.

He’d regularly cashed parlay tickets, even if he didn’t gamble elsewhere. He just knew he had a knack for picks, and he took out an ad in Game Plan magazine – $3,000 for a full page – offering his handicapping services. He was so-so in the early years, but by 1984, he scrounged enough money to start a newsletter, and two years later, he opened his own print shop to defer costs of his own newsletter while adding outside income. He usually slept on the couch in the shop, and he struggled to turn his picks into paper.

By 1989, nearing the age of 40, he was floundering, barely making any money. He needed a savior, but he ended up with an angel.

“Dad talked to me about six months before he died, and he wanted to be supportive, but he’s like, ‘You know, maybe you’ve done this long enough,’” he said. “Unfortunately, my dad died, but then he pulled some strings for me.”

Months after Henry died of cancer, Steele went on a run. He went 53-23 on his picks in 1989, and suddenly his tout service had legs. He remembers that year like it was yesterday; that first week, there were several six-point underdogs that Steele thought should be six-point favorites.

“It was like shooting fish in a barrel,” he said.

His hot streak continued the next year and the year after, and customers came flying in. There were no high-pressure sales tactics, Steele maintains. The movie “Two for the Money,” in which Matthew McConaughey and Al Pacino portray touts and degenerate gamblers? It was nothing like that, he says. Picture a half-dozen housewives answering the phones.

“I didn’t even like the stigma of having a sports service,” he said. “People would ask what I do, I’d say I have a print shop and I write a football newsletter.”

In 1994, Steele gathered all the best college football preview magazines in the country and realized his newsletter had better information than all of them.

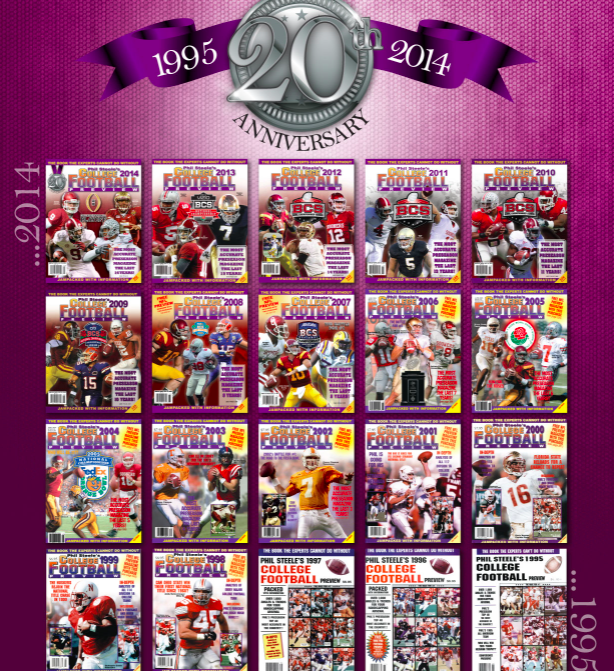

He started his magazine the next year. That first magazine was printed on black-and-white newsprint, with Lawrence Phillips and Danny Kanell on the cover, flanked by fellow stars like Leeland McElroy and Eddie George. It was 192 pages long. Only.

And it was a labor of love, even if Steele had no idea what he’d started.

* * * * *

By the mid-2000s, the focus of the magazine shifted, and so did Steele.

Since the beginning, there were obvious and not-so-obvious references to gambling – references to point spreads, betting angles – and Steele wanted to legitimize the magazine as an unbiased, straight-to-the-point font of information.

What really changed, though, was how he got that information.

Gone were the days of the “Fax Report,” when Steele would cull his information from a litany of sources across the country. On Sunday morning, faxes would come in from all over. One time, while trying to find dirt on a World League of American Football game, Steele found a source in Frankfurt. He’d gone international.

“Anything for an edge,” he said.

Besides, in those days, he was still living on a couch in the back of his print shop.

“When I’m sleeping on the couch, it would’ve been ludicrous to make a long-distance call,” he said.

Now he doesn’t need to make long-distance calls, even if trying to get Nick Saban on the phone is a Hail Mary. He goes directly to the source.

He remembers the first time he attended a Mid-American Conference Media Day. Then came the Conference-USA. Pretty soon he was getting phone numbers from coaches and having marathon chalk talks.

In 2004, he talked to around 20 coaches. The next year, 50. This year, he estimates he interviewed 110 of the 130 FBS head coaches, and these are not your average, get-me-off-the-phone type sessions. They typically last at least 90 minutes.

“There is probably nobody in college football who knows coaches better,” said Steve Richardson, Executive Director of the Football Writers Association of America. “Phil can basically pick up the phone and call just about any coach in the country. Sans maybe Nick Saban. They’ll tell him things for the magazine because it’s not directly from them. I was at an awards dinner several years ago and he walked in and you’d think he was coming down from the mountain top.”

A big thanks to Auburn head coach Bryan Harsin @CoachHarsin for taking an hour plus to go over his @AuburnFootball team with me today! #WarEagle #WDE pic.twitter.com/qlnaz9Rujh

— Phil Steele (@philsteele042) May 20, 2021

A big thanks to Penn State head coach James Franklin @coachjfranklin for taking the time to go over his @PennStateFball team with me today! #WeAre pic.twitter.com/gjc76UXNPU

— Phil Steele (@philsteele042) May 24, 2021

One of the reasons Steele remains in good graces: He sticks to football in a time when most reporters want to do anything but.

“He has built a reputation of being straightforward with these guys,” Wolpert said. “When you’re dealing with Power 5 football coaches, they don’t have time for nonsense. I guarantee they don’t always agree with what he writes or puts in the magazine, and you’re never gonna keep everyone happy. He’s not trying to do that. He’s trying to put out the most complete information that is honest and fair. There’s a lot of street cred there, and that doesn’t happen overnight. These are men who don’t often let people into their inner circle, who don’t accept everyone’s phone call.”

It’s not just that he sidesteps landmine questions that can make a coach blow up. And it’s not just that he’s honest and forthright with them.

He’s also a vault of information that would be worth big bucks on the open market.

“The amazing thing about Phil is probably half of what he has, he can’t use,” said his friend Ted Gangi, a fixture in college football media circles. “Coaches are forthcoming to him. The things that Phil knows – I always call it the stuff you can’t read in the newspaper.

“But his design, it can really make you blind.”

* * * * *

For loyalists of the magazine, the chaotic layout makes it only more charming. The pages could be 12 inches long and Steele would probably still find a way to fill the blank spaces.

This has become a yearly obsession for him. And for fans. He can rattle off dozens of customers who have collected every one of his issues. That makes him particularly proud.

“There is this romanticism about the college football preseason magazines that has existed for decades,” Richardson said. “I remember growing up in the 60s and I remember the year Archie Manning was on the cover of Street and Smith. A lot of people can’t wait to get it. There’s a nostalgia for it. It’s almost the signal that college football is getting near. We’ll see a tweet – ‘Just got Phil’s magazine. It’s getting closer!”

Two types of people in this world…those WITH a @philsteele042 CFB preview magazine, and those without.

I got mine, you get yours ??????

@ESPNCFB pic.twitter.com/WYj1pkyPdo— Rocky Boiman (@ROCKYBOIMAN50) July 25, 2021

But now with the official start of the season around the corner, Steele is back in his element.

Once the season ends for a team, then comes the fun part. Steele and his staff — which grew to 19 before the pandemic but now stands at 10 — capture and print out every single story that’s been written on a team during the previous year.

For some teams, like Akron, that might mean 60 pages. Ohio State? More like 1,600. And Steele reads every single story.

That, combined with a razor-sharp memory of the games from the previous year, forms the foundation for the magazine’s first pass. Steele will pound out his first two sets of power rankings, and he’ll spend from December through March essentially forming a recap of the previous season.

Usually, at the start of spring ball, freshmen and transfers have been added to rosters and Steele gets a better look at what teams will be working with. He does write-ups of every team’s eight units and he updates the power ratings. That’s the second run-through.

Then come the coach interviews, which take anywhere from a month to six weeks. He’ll incorporate their data into his spreadsheets and rankings, and finally, with a few weeks until deadline, he starts doing his offensive and defensive write-ups.

And then the final three days are devoted to his top-40 rankings, which he guards like they’re precious.

Every word in the magazine is precious to Steele, who serves as his own editor.

“I think there are a million words and numbers in this year’s magazine,” Steele said. “If you’re 99 percent accurate and 1 percent wrong, well 1 percent of 1 million is 10,000. I can’t have 10,000 typos in my magazine.”

With his encyclopedic knowledge of football, it begs the question: Is he some kind of savant? Does he just tear apart Jeopardy on a nightly basis?

“It’s the opposite,” he said. “I’m pretty clueless when it comes to anything besides the magazine. You could say, ‘Phil, you need to go to the grocery store,’ and it’s like, ‘I have to do what? Shop?’”

“I have a daughter who’s 15. She handles all the other stuff.”

* * * * *

Meet Savannah. She’s 15 and probably knows more about football than you do.

Not that she wants to, of course. She’s more into hockey.

She picks up on pigskin through osmosis, because most of what her father says is rooted in routes.

“He’s really good at what he does, but it kind of is his whole life,” she said. “I have to get him out of the football world sometimes. I try to get him to go out to stores with me. Maybe watch a movie that isn’t based on football.”

Steele calls Savannah “my co-pilot.”

One of the best days of his life was taking her to ESPN’s campus in Bristol, Conn., for the famed “car wash,” a non-stop tour of television and radio appearances. He did five SportsCenter hits that day, led around by a precocious 12-year-old who guided him by the hand.

“I would walk into ESPN and their radio section, a twisting labyrinth, and I’d just be wandering in the halls, and she’d pull me into the right room. If it’s not football, I’m really dumb.”

He sells himself short: Savannah said her father is great at helping with math homework. Not unusual, considering Steele thought he’d be an accountant growing up.

And she helps him with the magazine – laying out the photographs, proofing pages, stuffing magazines into envelopes to be shipped out.

During the summer, when the magazine has been put to bed, they get out and explore.

“In the summertime, we go on different adventures, (like) Cedar Point (Amusement Park),” she said. “I get him back during the summertime. But once October hits, he’s in his football world.”

And he doesn’t much look up.

“I remember I walked in the house when I was married (to Savannah’s mother, Rebecca), and I looked on the kitchen table and there was a plant. I told my then-wife, ‘Hey, that’s a nice plant!” he said. “She says, ‘it’s been there for a year.’”

* * * * *

The people around him implore him to change.

The printed word is a dying medium and Steele is like a dinosaur. He knows it. He knows that with his name recognition, a college football podcast would almost certainly be a hit. He has a blog that he doesn’t update regularly enough, and his Twitter lays dormant at times.

Imagine what could happen if he became Phil Steele Media.

Instead, he puts every ounce of himself into those 352 pages.

Why?

A simple answer.

“It has my name on it,” he said.

Others lament the missed potential.

“I think Phil is fighting it a little bit,” Gangi said. “He knows he has to evolve. He has a blog he doesn’t promote. The thing he has going for him is name recognition. The magazine is great, but the sport has evolved, the rosters, the coaching changes, the transfer portal essentially creating free agency. Phil is going to have to adapt. But Phil’s a smart guy. He will. I don’t know if that means putting out a digital version of the magazine when camp starts. But the more work you do, the more work you have to do. The more people expect from you.”

He knows the standard he’s set. The other college football preview magazines out there are barely half the size of his.

“Some people refer to it as the bible,” he said. “It’s my job to keep that going. It’s my job to make sure there’s no let-up. When I tell you it’s my life, it’s my life. There really is nothing outside of football. I can’t imagine it.”

For good or for bad?

“I’m gonna say good,” he said. “My daughter says you should do more, go to a bar. I can be working on football, what can be better? It’s all worth it, in the long run. I tell my daughter, I was this little kid in Cleveland, Ohio, and now I’ve got a magazine everyone in the country knows. I didn’t have money. I didn’t have connections. I wasn’t a coach. I wasn’t a writer. I knew no one in the publications business. And now I have this.

“If you put everything you have at something, you can be successful at it.”

Jon Gold has won multiple state and national awards covering college football. He is the Pac-12 columnist for Saturday Out West.