When March was truly madness. Reliving Duke vs. Kentucky 1992, and how it led us to where we are

By Joe Cox

Published:

26 years ago today, Grant Hill threw a pass to Christian Laettner, the start of a play that broke Kentucky fans’ hearts.

LEXINGTON — It is the time of year when déjà vu can arise in a moment. This year, it was a second round game — Houston vs. Michigan. Houston led by two, 3.6 seconds to play, Michigan with the length of the floor to travel. And then, just before the play, there was the flicker of recognition.

“Are they going to guard the ball?”

They didn’t. Michigan, thus free to inbound, ran the ball down the floor, got off a 3 at the horn, and when it dropped through the basket, celebrated by piling onto each other like the group of ecstatic college kids they were.

“How do you not guard the inbounds pass?” tweeted a friend, a UNC fan.

“Been asking since 1992,” I replied.

*****

Perhaps the hardest thing to believe about UK vs. Duke 1992 was that UK was a big underdog. You had to be there. Kentucky went 13-19 in 1989, its first losing season in more than 60 years. Worse, the Wildcats had a package of cash mysteriously fall open in transit. If that was the smoke, the fire nearly burned down Kentucky’s program. Scholarship reductions, a year without live TV, two years without postseason play. The NCAA admitted that it had considered the “death penalty.” Coach Eddie Sutton was gone, so was athletic director Cliff Hagan. The top two players from the 13-19 team transferred (LeRon Ellis to Syracuse, Chris Mills to Arizona).

What was left? Nothing.

Kentucky returned a talented but underachieving senior guard, Derrick Miller, a scrappy but not star level 6-7 post player, Reggie Hanson, and the dregs of the worst team in memory. Five other scholarship players returned — they had combined to average about nine points per game for the 13-19 team. None was taller than 6-7, none was a highly decorated recruit, but three of the players hailed from Kentucky and a fourth spent much of his childhood visiting from nearby Indiana.

The Wildcats got a new athletic director (C.M. Newton), a new coach (Rick Pitino), and a new system. Talent was non-existent. Execution and desire would have to suffice. The Wildcats shot 3s, they ran an aggressive full-court press, and they outworked their opponents. The 14-14 season in 1989-90 might have been the most joyous campaign in UK history. The four sophomores who stuck around — Sean Woods, a Prop 48 casualty from Indiana, and a trio of Kentucky kids, Richie Farmer, Deron Feldhaus and John Pelphrey, became icons.

One memorable night in conference play, the Wildcats hosted LSU. UK had lost by 13 at LSU, and the Tigers had a starting five that included Chris Jackson, Shaquille O’Neal, and 7-foot first round NBA draft pick Stanley Roberts. Kentucky, with no player taller than 6-7, was outrebounded by 17. But they forced 24 LSU turnovers, and pulled an unthinkable 100-95 win.

On a small level, Kentucky basketball was back on that glorious night in February of 1990.

On a larger level, the Wildcats still had plenty to prove. With Pitino adding the first of many big-name recruits, New York forward Jamal Mashburn, Kentucky suddenly made up some ground in talent. The Wildcats had the best SEC record in 1991, but because of their probation, could not claim the SEC title or play in postseason tournaments.

But in 1992, the shackles of probation came off. Woods, Farmer, Feldhaus and Pelphrey could compete for an SEC title … and maybe even make an NCAA Tournament run. It wasn’t a brilliant Kentucky team. They still lacked inside play, and their only player who ever saw the court in an NBA game was Mashburn, who was still a work in progress as a sophomore.

The Wildcats won the SEC East, got lucky enough to draw a Shaq-less LSU team in the SEC semifinals, and then won the SEC Tournament against Wimp Sanderson and Alabama. They got a No. 2 seed in the NCAA Tournament and three games later (including a hard-fought 87-77 win over UMass and young coach John Calipari), The Unforgettables arrived in the Eastern regional final against Duke.

****

If it’s hard to imagine a Kentucky team led by four seniors without a shred of NBA ability, take a look at 1992 Duke’s roster, and consider the likelihood of seeing it matched anytime soon. Christian Laettner entered his senior season with more than 1,700 career points scored, a national title under his belt, and as the de facto best player in the college game. Junior Bobby Hurley had outplayed UNLV’s lottery picks in the previous NCAA Tournament, but returned for his third season at Duke. Meanwhile, sophomore Grant Hill had scored 11.2 points per game in helping Duke to the 1991 title, and had showed phenomenal athleticism in doing so. It was 1992, so he was in college for four years. Six players on Duke’s team reached the 1,000 point mark. It’s rare for Duke to keep even one player like that now.

Duke was the defending champion, the best team in the nation. They lost twice all year — by two at North Carolina and by four at Wake Forest. They had the skills, the swagger, and the best coach in the sport. So some things haven’t really changed. But Duke had been crowned champion for the first time the previous March. They were still a team forging its identity.

****

On March 28, 1992, arguably the greatest game in the history of college basketball was played between Duke and Kentucky. The two teams combined to shoot over 61 percent, which is a testament not to the lack of defense, but to the excellent offensive execution shown. Each team shot at least 50 percent from 3-point range. It became a game of “Can you top this?”

Duke led by five at halftime, 50-45, and had stretched its advantage to a dozen points in the second half before Kentucky’s press-and-three attack hit its run. The game was tied, and it went into overtime. Mashburn, who had been excellent, fouled out with 28 points and 10 rebounds. Laettner, still in the game after stomping UK reserve Aminu Timberlake in an incident that earned him a technical foul, simply could not miss. Shot after shot found the bottom of the net.

With the game clock running down and Kentucky trailing by one, Sean Woods, one of the seniors who had stuck it out in Kentucky’s darkest days, hit a running bank shot to give UK a 103-102 lead. Mashburn, from the bench, threw his hands in there. There it is, he seemed to say.

And across Kentucky, the celebration began. It was a rare moment of vindication as a David for a program that had been the unholiest of Goliaths. Maybe this was the payback, thought the UK fans who had suffered through the dark ages. Maybe getting busted paying players and messing with standardized test scores and running a filthy program created a shot at redemption. Maybe it gave UK a chance to do things right — with a coach whose style begat excitement, with players who were short on talent, but long on experience and pure of heart.

In the mountains of eastern Kentucky, I was 11 years old. My memories of pre-Pitino Kentucky basketball were scant. But it had become the greatest show on hard wood. And now, I was seeing my own chapter of glory. It was amazing. It was pure. It was doomed.

“Are they going to guard the ball?”

****

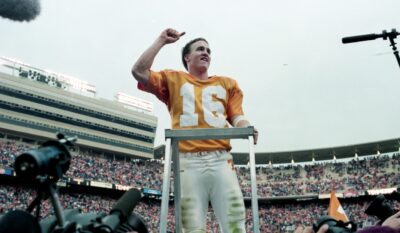

Pitino didn’t have any of his undersized Wildcats guard the ball on the inbounds pass — the type of hubris that has defined his weakest moments. Just 2.1 seconds remained when Grant Hill threw a baseball pass to Laettner. Pelphrey and Feldhaus, maybe already celebrating, maybe just shocked to be there, stood and watched. Laettner caught the ball, turned, shot, made the basket that ended the dream. Duke 104, Kentucky 103.

Victorious players and defeated players alike collapsed to the floor in tears. So did an 11-year-old boy in eastern Kentucky. March is the cruelest month.

****

Twenty-six years on — on the anniversary of that game — what stands out isn’t the elation of Woods’ shot or the devastation from Laettner’s answer. It’s a few simple facts. The NCAA Tournament is the greatest spectacle in sport because it gives people a chance to pit David against Goliath, year after year, bracket after bracket. But like any other sport, in the end, Goliath usually has his way. Sure, there’s the occasional 1983 N.C. State, 1985 Villanova or 2014 UConn team. But there’s a lot of UCLA and Kentucky in that record book. And North Carolina and now Duke.

Also, the UK-Duke game stands out because it was a signpost. What college basketball used to be, down that way. What it’s going to become, that direction. It won’t go back. That Duke-UK game was full of thoroughly-honored veteran players, competing in a highly skilled game. We might see basketball go to a 6-on-6 format before Kentucky has four significant players who are seniors or three who are from Kentucky. We might see a four-point shot added before a player like Grant Hill will stay four years again at Duke.

Kentucky lost the ability to claim underdog status that night. Four years later, Pitino won the school’s sixth NCAA title. Two years later, Tubby Smith added another one, and after a 14 year-exile that included a tour of Billy Gillispie-land, Calipari won yet another. The players get younger, fewer hail from Kentucky, but they still win plenty of games.

Pitino’s legend was remade (1996 title, near 1997 title), torn down (Celtics failure), remade again (Louisville success), and torn down again (UofL scandal). It would be silly to pretend that part of the drive that made his hubris run into overdrive wasn’t his own inability to adapt to the new ways.

Duke’s legacy was sealed that night — the Blue Devils became the face of college basketball, loved or hated, but never targeted for indifference. They often had the best players — and the ones you most wanted to punch in the mouth. But they won, too.

That said, neither Duke nor Kentucky advanced to the Final Four this year. Loyola-Chicago did. Maybe, in the end, David will laugh last at all the Goliaths.

Let’s hope he guards the ball this time.

Joe Cox is a columnist for Saturday Down South. He has also written or assisted in writing five books, and his most recent, Almost Perfect (a study of baseball pitchers’ near-miss attempts at perfect games), is available on Amazon or at many local bookstores.