Film study: Dave Aranda’s agenda for revitalizing LSU’s pass rush

By Matt Hinton

Published:

A weekly look inside an SEC playbook.

High expectations come with the territory at LSU, as much a permanent fixture of the landscape as I-10 or the summer heat. Even before the ink was dry on the Tigers’ 10-3 finish in 2015, though, it was clear that 2016 was going to be one of those years, the culmination of a four- or five-year cycle in which the constellations come into alignment for a serious championship run.

The brightest star, of course, is Leonard Fournette, back for his final college campaign in all his Taurean splendor before leaving early for the NFL. But there’s also a blue-chip quarterback with a full season under his belt as the starter, flanked by a pair of NFL-ready wideouts and a long-in-the-tooth offensive line. And there are 10 returning starters on defense, at least two of whom, linebacker Kendell Beckwith and cornerback Tre’davious White, passed on the draft for a chance to go out on top as seniors. The looming mass exodus to the next level in 2017 only adds to the feeling that the time is now.

Altogether, the Tigers boast more senior starters and return a higher percentage of last year’s production on both sides of the ball than any other team in the SEC; accordingly, they’ll take the field for Saturday’s opener against Wisconsin ranked fifth in the preseason AP poll, LSU’s first top-10 projection since 2012. (It hasn’t finished in the top 10 since 2011, the last time a Les Miles team won the SEC or played for a championship of any kind.) The most important difference in 2016? Experience.

Yet for all the familiarity on the field, the most compelling argument for a breakthrough this fall might be a new arrival in the press box: Dave Aranda, who last winter graduated seemingly overnight from a promising, obscure young assistant into one of the most sought-after — and lavishly compensated — defensive coordinators in the nation.

At his last job, Aranda turned Wisconsin’s defense from a solid but unremarkable group into an aggressive unit that led the nation last year in scoring defense, ranked second in total D, and held every opponent except one (Alabama, in the first game) at least 40 yards below its season average for total offense.

In two of their three losses, the Badgers yielded just 10 points to Iowa and 13 to Northwestern, and closed the year by holding USC to a season-low 286 yards in a 23-21 upset in the Holiday Bowl. Two days later, Aranda accepted a $1.3 million deal to deliver the same results to Baton Rouge, with the implicit promise that his success could be the final, crucial piece of the championship puzzle.

At LSU, he’ll inherit more raw talent than he ever could have dreamed of Madison, where the depth chart consisted almost entirely of former three-star recruits and walk-ons. But thus far all that next-level potential has remained just that: Last year, the Tigers ranked fifth in the SEC in total defense, 10th in scoring, and 12th in pass efficiency, at one point yielding 99 points over the course of the three-game November losing streak that nearly sentenced Miles to an early retirement.

They forced fewer turnovers (17) than any LSU defense since Miles’ first season in Baton Rouge in 2005. Aranda’s mandate is to close the gap between those mediocre returns and the dominant numbers he’s accustomed to. If he pulls it off, the results will be worth every penny.

A BUCK BY ANY OTHER NAME…

On paper, LSU is transitioning from the standard 4-3 look that has served as its base defense throughout Miles’ tenure to the 3-4 scheme Aranda employed at Wisconsin, a move accompanied by the usual docket of position changes: Defensive tackles become defensive ends, ends become outside linebackers, outside ‘backers move inside, and so on.

Particular emphasis in dissecting the 3-4 often falls on the role of the 2-gap nose tackle, the comically large “war daddy” tasked with gumming up the middle of the line of scrimmage by taking on multiple blockers by himself; sure enough, LSU added a couple natural-born 2-gappers over the summer in true freshman Ed Alexander (6-2, 333 pounds) and JUCO transfer Travonte Valentine (6-4, 356).

In reality, though, the concept of a “base” defense is as archaic here as it’s becoming across the sport at large. Like most modern schemes, Aranda’s blueprint for defending spread offenses emphasizes versatility: Multiple formations, manned by players flexible enough to handle multiple positions in response to hurry-up attacks that limit substitution.

In that sense, the difference between a 4-3 and a 3-4 — or, say, a 3-3-5 set on passing downs and a 2-4-5 — is becoming more and more semantic. Defensive end Lewis Neal, for example, will play with his hand on the ground in certain situations (the better to hold his own against the run) and as a stand-up, pass-rushing outside linebacker in others; ditto Tashawn Bower and Arden Key, who have been nominally converted from end in the old scheme to OLB and “Buck,” respectively, but likely won’t be facing much of a learning curve — these days, it’s more accurate to classify them all as “edge rushers” regardless of the formation.

Whatever label you put beside their names, their job description is still primarily to get to the quarterback as early and often as possible.

The chief advantage of a 3-4 is the sheer variety of options it gives them for getting that job done.

At Wisconsin, Aranda earned a reputation for devising unique ways of making opposing QBs uncomfortable, and especially for using pre-snap alignment to disguise where the pressure would be coming from out of a given look.

The main beneficiaries there were a pair of relatively undersize outside linebackers, Joe Schobert and Vince Biegel, neither of whom fits the mold of a prototypical NFL (or SEC, for that matter) pass rusher. Still, in Aranda’s scheme they combined for 52.5 tackles for loss and 22 sacks over the past two years and emerged as one of the most productive pairs of bookend blitzers in the nation. (Wisconsin’s linebackers as a group led the nation in 2015 in havoc rate, or the percentage of all plays resulting in a TFL, sack, forced fumble, interception, or defensed pass.)

Schobert, once a 6-foot-nothing walk-on, landed on multiple All-America teams last year as a senior and was drafted in the fourth round by the Cleveland Browns; Biegel, now the undisputed leader of the Badgers D with Schobert gone, expects to hear his name called next year.

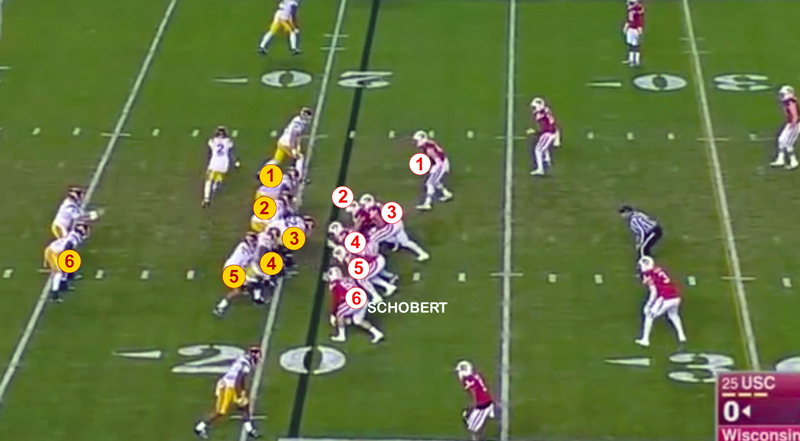

Schobert, especially, was a perfect fit for Aranda’s array of formations and pressures, easily making up whatever he lacked in imposing athleticism with instincts and veteran savvy. Take this play, an obvious passing down (3rd-and-9) in the first quarter of the Badgers’ win over USC. Before the snap, Wisconsin counters the Trojans’ four-wide formation with a 3-3-5 look, offering six potential rushers against six blockers (including the running back) on offense. Schobert is the end man at the bottom of the screen, telegraphing the blitz.

At the snap, Wisconsin rushes four — three down linemen plus Schobert — with the outside linebacker to the top of the formation dropping into coverage.

The nose tackle (No. 4 in the above screenshot) and defensive end (No. 5) to the bottom of the formation slant to the right side of the offensive line, occupying the center and right guard, respectively; Schobert’s first move is upfield, occupying the right tackle, who is essentially on an island against one of the best rushers in the Big Ten. And although the middle linebacker (No. 3 above) does not blitz, the fact that he showed blitz before the snap and does not immediately drop into coverage at the snap is enough to occupy the attention of the left guard, who is initially left blocking no one.

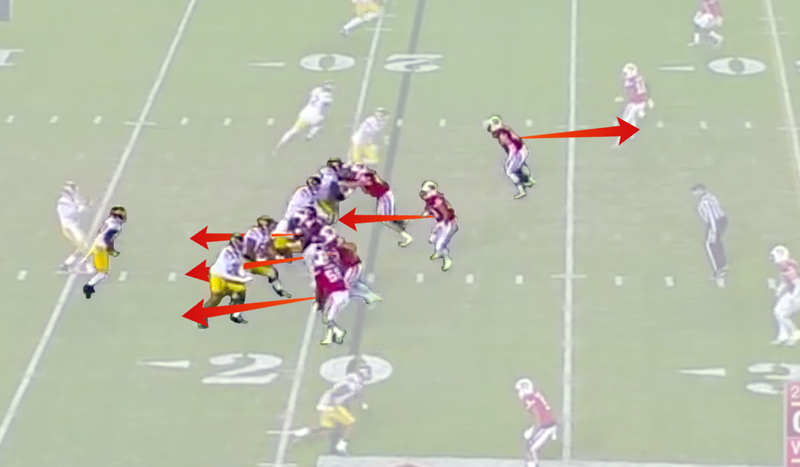

After his initial feint to the outside, Schobert peels back to execute a move Aranda calls a “twist cat,” looping into the middle of the line behind the slanting NT and DE; in effect, those two are acting as “blockers” to create a lane for Schobert.

Theoretically, USC should still have enough bodies to handle this — after all, with two linebackers dropping into coverage it’s still six blockers vs. four rushers. But neither the center (engaged in a double team with the nose tackle) nor the left guard (still eying the middle linebacker) has the wherewithal to fill the gap vacated by the nose, leaving a wide open path into the backfield.

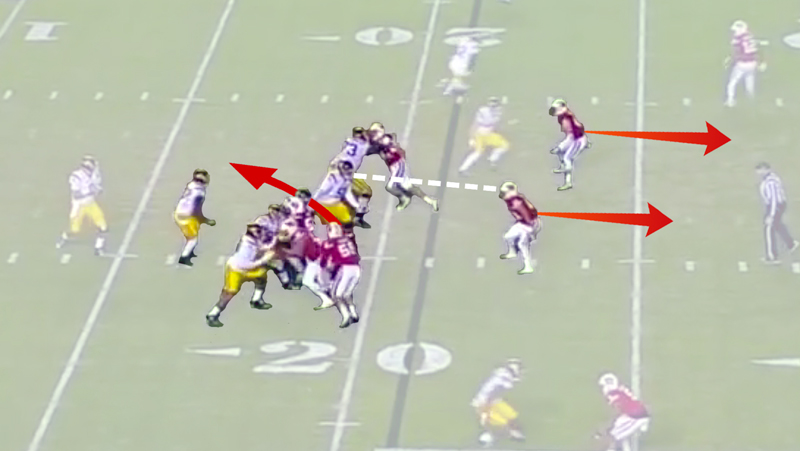

From a different angle Schobert’s lane to the quarterback is more obvious; by this point, the running back (also apparently keying on the middle linebacker) has abandoned his blocking responsibilities and is looking to become an outlet receiver, while the left guard (No. 51) has recognized the twist far too late to do anything about it. He’s so far out of position …

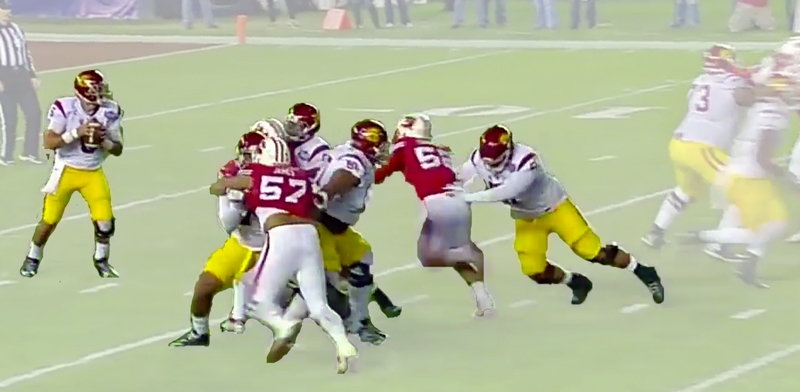

… he winds up lunging ineffectually as Schobert blows past him and on to a free shot at QB Cody Kessler.

In real time, this all takes about two seconds:

And the result, somehow, was a successful play for USC: Despite the confusion up front, Kessler managed to elude Schobert’s grasp, regain his composure, and deliver a first-down throw to his tight end.

But Aranda’s scheme accomplished exactly what it was designed to accomplish, freeing up his best player for a better-than-even shot at a sack with a standard four-man rush, leaving seven defenders on the back end to cover five receivers. The vast majority of the time that is not going to end well for the offense — just as it ultimately didn’t for Kessler, who was sacked three times on the night and turned in one of the lowest-rated outings of his career in his final college game.

THE MASTER KEY

As successful as Aranda was at Wisconsin, one luxury he never enjoyed there was the presence of a blazing edge player with the juice to beat offensive tackles one-on-one on a regular basis. At LSU, he’ll have one of the most finely tuned speed rushers in the nation: Only a sophomore, Key is already squarely on the radar of NFL scouts despite his beanpole frame (officially, he’s listed at 6-foot-6, 238 pounds) and an inconsistent freshman campaign that yielded five sacks — respectable, for a rookie, but nothing that’s going to get anybody’s pulse racing. On film, though, he was often much more dynamic than the stat sheet suggested.

Take Key’s best game last year, in LSU’s 19-7 win over Texas A&M in the regular season finale, where he was credited with eight tackles and 1.5 sacks. A perfectly nice stat line, but not nearly a complete account of his actual impact. Here’s Key early in that game, for example, easily swatting aside an H-back and a running back en route to quarterback Kyle Allen, who responds by retreating directly into the arms (and the stat sheet) of Lewis Neal:

And here he is a little later, torching A&M’s left tackle and supplying the initial pressure that results in Allen fumbling away a prime scoring opportunity inside the LSU 10-yard line:

It’s no coincidence that (like the Schobert sack outlined above) both of those pressures came on third down, in more or less obvious passing situations that allowed Key to tee off without having to worry about running himself out of position against the run.

On a down-to-down basis, his size remains less than ideal for taking on and shedding blocks. But on third-and-long, or in a two-minute drill with a lead to protect, Key’s first step and closing burst are as lethal as anyone’s in the college game.

TO SATURDAY AND BEYOND. The hardest part of forecasting Aranda’s impact on LSU before having a chance to see his defense in action is the difference between LSU’s personnel and Wisconsin’s — honestly, how much sense does it make to design stunts and twists for someone like Key who is equally (or more) likely to simply blow by an offensive tackle at any time?

How will he deploy ball-hawking junior Jamal Adams, a five-star talent who potentially ranks among the most versatile and disruptive safeties in the nation? Will LSU’s man coverage potential in the secondary free up the front seven to be even more aggressive, or more creative? And last year, Aranda’s third at Wisconsin, was a significant improvement on his first two; how much of his system can his new charges absorb in year one?

Saturday’s debut against Aranda’s old team should offer some initial clues, if nothing else for how well Key holds up against an old-school power running team, and for just how deep the front seven goes with a pair of projected senior starters (lineman Christian LaCouture and linebacker Corey Thompson) already sidelined by injury. But there shouldn’t be any question that whatever Aranda wants to do schematically, he has the athletes to do it, and then some.

If the system meshes with the talent on hand as well as it did at his last stop, the ceiling is the limit for the 2016 Tigers and for Aranda’s stock as a head coaching candidate in the very near future.

Follow Matt Hinton on Twitter: @MattRHinton.

Image Credit: USA TODAY SPORTS

Matt Hinton, author of 'Monday Down South' and our resident QB guru, has previously written for Dr. Saturday, CBS and Grantland.