Destination unknown: Getting personal with Dak Prescott at the 2016 NFL Combine

By John Crist

Published:

My phone rings. The caller ID reads “Dak Prescott.” He’s getting back to me shortly after I left him a message. Turns out he was in the middle of a workout. He’s still out of breath.

It’s Monday. I’m in Tampa. He’s in Orlando. But by Wednesday, we’ll both be in Indianapolis for the Scouting Combine — the annual meat market for college players ahead of the NFL Draft. I’ll be there as a member of the media. Prescott, of course, is a prospect following a spectacular career at Mississippi State.

He’s the best quarterback ever to play in Starkville, and he may just be the single best player in school history. Prescott elevated a mediocre program in a brutal conference to heights never seen before.

Nevertheless, when the draft experts go through the list of top QBs, his name isn’t mentioned. Jared Goff of California, Carson Wentz of North Dakota State — yes, FCS-level NDSU — and Paxton Lynch of Memphis are considered the first-tier passers. Prescott is a second-tier guy alongside the likes of Michigan State’s Connor Cook and Penn State’s Christian Hackenberg.

He’s currently projected as a mid-round pick. But if Prescott is worried, he hides it well. He sounds authentic and confident without an iota of cockiness.

“(Other quarterbacks) are going to get their hype,” he says. “Just going to camps, even the combine, I don’t know that I’ll make people drop their pen and drop their jaw and say, ‘We’ve got to get this guy first off the board.’ That hasn’t been the player I’ve been all my life.”

Prescott’s scouting report is short on measurables. The combine is all about measurables. Descriptions like “leader” aren’t input on a spreadsheet. All 32 teams will be in attendance, and they’re hunting for players. But they want blazing 40s and Howitzer arms, not intangibles.

“I’m a guy that’s improved every year of my life,” he says. “Not just in high school, not just from that transition, but every single year I find my weakness from the year before and I try to make it a strength.”

The NFL community will find weaknesses that he never knew he had. Maybe his hands are too small. Maybe his delivery is too long. That confidence I heard in his voice might not survive all the nitpicking in Indy.

i. ‘don’t come in here crying to me’

Rayne Dakota Prescott was born July 29, 1993, in Sulphur, a city of about 20,000 people in southwestern Louisiana. Near the middle of Calcasieu Parish, the town got its name when sulfur was discovered in 1867.

The son of Nathaniel and the late Peggy Prescott — she succumbed to colon cancer in 2013 — Dak grew up with two older brothers, Tad and Jace. Football was a part of life for the Prescott boys, especially after their parents split up and they relocated to Haughton. Tad and Jace are five and six years older than Dak, respectively, but that didn’t stop the youngest from participating in neighborhood pickup games.

Dak was six years old. His brothers were 11 and 12. Most of the other kids were closer in age to Tad and Jace. But nobody made an effort to take it easy on little Dak. Nobody.

“There were times that I’d come home crying because I was hit too hard,” he says. “My mom would tell me, ‘Then don’t go back out there. Don’t come in here crying to me.’ I always give them credit for making me tough.”

While Dak was the smallest, he was also the most skilled. Tad once had six sacks in a high school game. Jace played collegiately at Northwestern State. But even at six, Dak had the brightest pigskin future.

“They didn’t mind me playing because I wasn’t going to ask them to play touch on me or take it lightly on me,” he says, “and they sure enough didn’t.”

Dak began playing organized football at eight. By the time he was a middle schooler, the coaching staff at Haughton High School was counting down the days.

Coach Rodney Guin built Haughton’s offense — a spread-type system — around Dak’s many talents. As a passer, he threw for more than 5,000 yards and 66 touchdowns. As a runner, he recorded 950 yards and found the end zone 17 times his senior campaign alone. That year, he directed Haughton to its first undefeated regular season in school history.

However, the recruiting services didn’t seem impressed. First a two-star prospect, he had to fight for a measly third star. But that was it. Dak fell through the cracks on the camp circuit, too.

“I’m not a guy that’s going to blow you away on testing day,” he says. “I would go to all these college camps. Not many of them made us run the 40, but some of them did. I was running 4.8 I guess at the time, so nobody was amazed by my speed.”

What set him apart, he says, wasn’t quantifiable.

“Leadership ability, at camps you don’t get to necessarily see that, and you don’t get to see all the other things that go into the quarterback position.”

TCU wanted him, but the Horned Frogs also had eyes for Trevone Boykin. LSU wanted him, but the Tigers recruited him as an athlete. Dak only viewed himself as a quarterback.

Mississippi State wanted him most of all. Starkville felt like home. He committed and never looked back.

ii. ‘it’s been non-stop’

Prescott touches down in Indianapolis on Wednesday with the rest of the quarterbacks, wide receivers and tight ends. His schedule includes registration, pre-exam and X-rays at the hospital, orientation and, finally, interviews with NFL teams.

Along with the rest of the media, I spend a few minutes here with Ole Miss offensive tackle Laremy Tunsil and a few minutes there with Arkansas running back Alex Collins, among others.

So far this week, Prescott has been responsive via text more often than not. But once I leave Lucas Oil Stadium at six o’clock, Prescott still has not replied to a message from hours earlier — the plan going in was to meet nightly. Eight o’clock becomes nine o’clock. Then nine becomes ten. Not a word. Writing a behind-the-scenes story is much harder if you never actually get behind the scenes.

After I give up and go to sleep, a text hits my phone from one of Prescott’s representatives at ProSource Sports Management, Walter Jones. I don’t get it until morning. 11:28 p.m. was the time stamp:

“Dak just texted. He is just finishing up with his last informal meeting. Said it’s been non-stop.”

Prescott was meeting with teams at his hotel for approximately four and a half hours. Every time he closed one door, he was being pulled through another. It appears teams are interested.

iii. ‘we got this’

Haughton’s chief rival in northwestern Louisiana is Parkway High School. Separated by less than 20 miles, the Buccaneers and Panthers know each other well.

With one minute remaining in the 2009 district championship game, Parkway scored to take a 38-35 lead. Dejected, the Haughton players and coaches thought their season was over. But one person on their bench wasn’t rattled: Prescott, just a junior at the time.

As Guin remembers it, the ensuing Parkway kickoff rocketed into the end zone for a touchback. Without much of a kicking game, Prescott would have to drive 80 yards with only seconds left.

“As Dak left the sideline,” Guin says, “he came up to me and said, ‘Coach, we got this.’”

The Parkway defenders were expecting Haughton to go long, so Prescott took advantage of the prevent coverage. Seven yards. Nine yards. Eight yards. Suddenly, the Bucs were threatening.

“I just threw hitches,” Prescott says. “I probably threw five hitches in a row, the receivers catching the ball and getting out of bounds.”

The drive wasn’t all gimmes, though. Haughton eventually had to pull a rabbit out of its hat on third-and-18. It was the old hook-and-ladder that moved the sticks and put the Bucs in scoring range.

Parkway was reeling, even with the clock close to zeroes. With twin receivers to his right, Prescott called for a post-wheel combination. The outside receiver would run the post, while the inside receiver would run the wheel — a quick out toward the boundary before turning up the sideline straight to the pylon.

Despite the frenzy, Prescott could sense Parkway’s confusion. He took the snap as quickly as possible.

“They left the wheel route wide open,” “he says. “I threw it to my right for the touchdown.”

Haughton had won the district over hated Parkway, 41-38. Guin didn’t see it coming. His players didn’t see it coming, either. Except one: the kid telling anyone who would listen, “We got this.”

“To him,” says Guin, “there was never a doubt about the outcome.”

That was the moment Guin realized he might have a future NFL star in his stable. While Prescott went on to have a prolific senior season, it was the comeback over Parkway junior year that made him a Haughton hero.

iv. ‘always had a smile on her face’

Meeting people that might pay him big money to play football trumps any obligation Prescott may have to spend time with me. Jones and I trade messages. Everything’s fine.

The highlight Thursday for Prescott — at least for fans following the Scouting Combine from home — is his media interview. NFL reporters descend upon Indianapolis at this time every year, but they usually don’t lob the kind of softball questions he got used to answering in college. A lot of players loathe this part of the process, even more so than the medical exams.

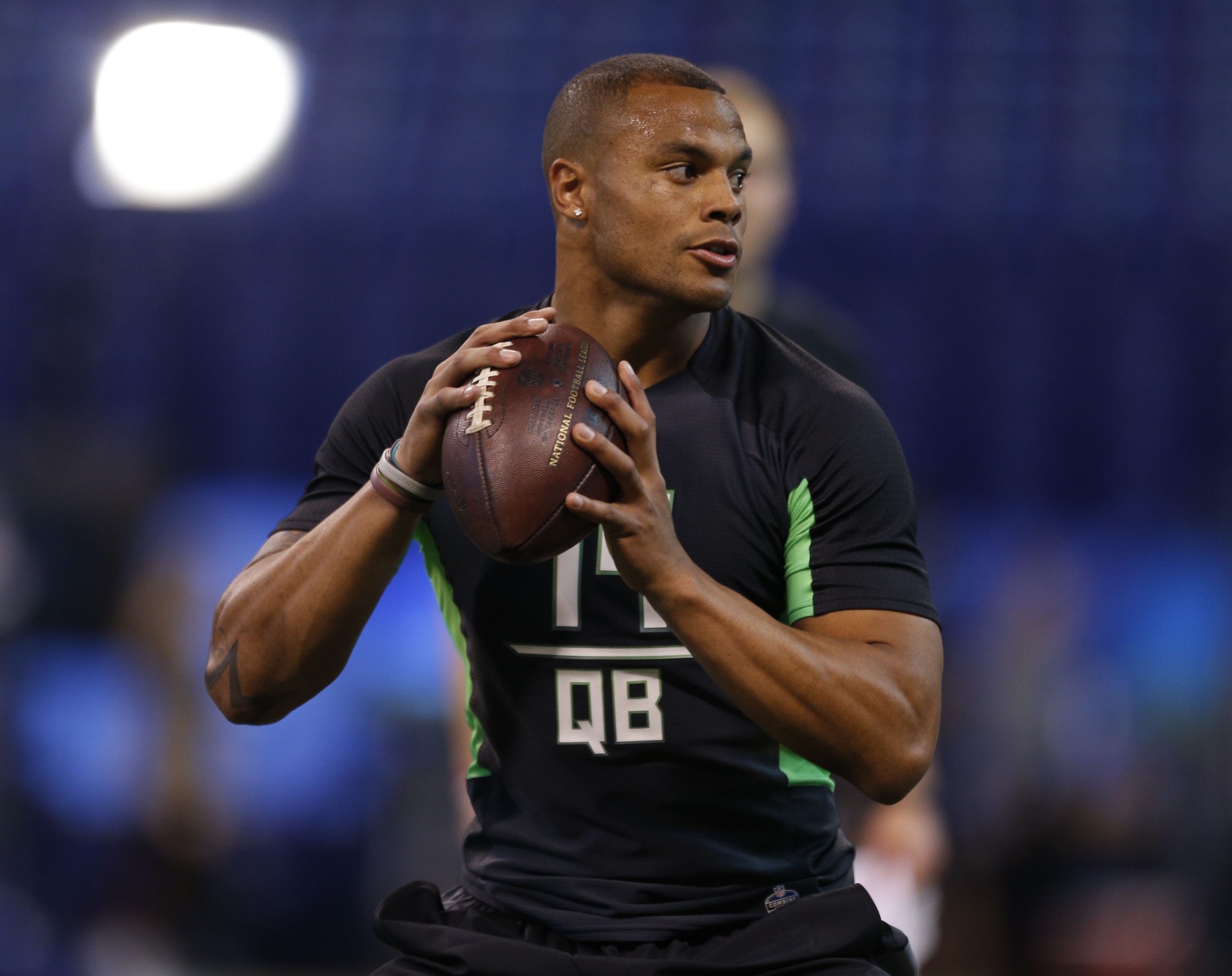

A little after two o’clock, the NFL’s media relations staff makes an announcement over the loudspeaker: “Mississippi State quarterback Dak Prescott, Podium B.”

From head to toe, he’s decked out in combine-issued Under Armour gear. While he may have worn No. 15 for the Bulldogs, this week he’ll be identified as “QB14” — each position group is arranged alphabetically.

He’s handsome. He’s got a fresh haircut. If scouts were testing cheekbone height and jawline strength, Prescott might be in the running for the No. 1 pick.

Unlike a lot of players that tend to mumble their responses in hushed tones, Prescott projects his voice and annunciates every word perfectly. No “ums” or “you knows.”

The Q&A is a standard affair. He talks about working on taking snaps from under center and proper drops in the pocket — he didn’t have to in high school or college. One reporter from Dallas has a Cowboys-related question, as Prescott was a fan as a kid. When asked what sets him apart from some of the other QBs in Indy, he points out his leadership.

He has a near bulletproof reputation for being a saint in Starkville. (Read some of the responses on his Facebook fan page.) His mother taught him to give to others, so he closes the interview talking about her influence.

“She just gave back to people, always had a smile on her face, was optimistic about everything in every situation, and it just kind of carries down,” he says. “Just watching her allows me to carry through life the same way.”

v. ‘a family vibe’

Escorted out of the media room by a member of the NFL staff, Prescott’s next stop is an interview with SiriusXM NFL Radio. Host John Hansen and NFL Films guru Greg Cosell spend a few on-air minutes with him. Cosell compares him to former Pro Bowler Donovan McNabb.

As he reaches the secure area where no media are allowed, finally I get a chance to introduce myself in person. He apologizes for not being more available.

The rest of his day is packed, and now he’s on his way to the dreaded medical exam. It’s two-thirty. His meetings with teams don’t begin until seven-thirty. He and I make arrangements to meet in the lobby of the Omni at six, which is across from where he’s staying at the Crowne Plaza.

About an hour later, Prescott is still at the hospital, but now he has to meet his position group — meaning the rest of the quarterbacks — at six.

I respond with a request to move our meeting back to six-thirty. In the meantime, I reach out to Jones and ask to meet him and the rest of the ProSource team. I can chat with them before Prescott joins us.

I get to the Omni at six. Jones waves me over to his table, where ProSource has gathered. Jeff Guerriero is Prescott’s agent. He owns the company with his wife, Elizabeth — she also happens to be certified by the NFLPA. Rick Roberts is in charge of client relations and makes the arrangements for each player’s training. As for Jones, his specialty is media, branding and endorsements.

Jones does his best to keeps tabs on Prescott. Six-thirty is in the rearview mirror by now, yet he’s still at the hospital. He missed his meeting with the QBs. By seven-fifteen, it’s clear he won’t be showing up.

While I miss yet another chance for a 1-on-1 with the actual subject of this story, I do get to know the ProSource people. As agencies go, this is a small outfit — not exactly Madison Avenue. Based in Monroe, less than 90 miles from Haughton, they’re country. But the Guerrieros, Roberts and Jones give off a family vibe, which is what Prescott wanted. He didn’t meet with any other agency.

Upon leaving, I tell Jones that I have a dinner reservation Saturday at St. Elmo. I make him promise that Prescott will be my date. Jones assures me it will happen.

vi. ‘i’m my own person’

Getting compared to Tim Tebow is a compliment for a college quarterback. The first sophomore to win the Heisman Trophy and a two-time national champion, he is a god-like figure in the SEC.

But getting compared to Tebow as an NFL prospect is the furthest thing from a compliment. Denver Broncos team president John Elway was so impressed with Tebow’s playoff victory over the Pittsburgh Steelers that he traded the former first-round pick for a kicking tee the following offseason.

For Prescott, the comparisons are impossible to avoid. He played at Mississippi State for Dan Mullen, who was Tebow’s offensive coordinator at Florida. Both are built like H-backs. As with Tebow, Prescott’s highlight reel is filled with just as many punishing runs as pristine passes. Each wore No. 15, too.

Mullen has been quoted as saying Prescott is the best player he’s ever coached, and that includes Tebow.

“The two get compared often because of their leadership and the character they have displayed throughout their careers,” Mullen says. “However, they are completely different quarterbacks on the field.”

It’s not unusual for the signal caller in Mullen’s offense to run the ball 20-plus times in a game. He is always in the shotgun. Huddles are few and far between. NFL-caliber throws are hard to find on tape. Many passes are pre-determined. That may work against Arkansas, but it doesn’t work against the Seattle Seahawks.

While Tebow is one of the best college players we’ve ever known, a lot of what he did was guts, guile and being surrounded by superior teammates. He didn’t have that luxury in the pros, and neither will Prescott.

“It’s motivation just to go out there and show people I’m my own person,” says Prescott, “not to compare me to anyone.”

Tebow didn’t even throw in Indianapolis, choosing instead to wait until his Pro Day. He knew his motion needed work. Prescott, on the other hand, will be putting his arm on display for everyone to see.

As for the comparison, I ask Cosell, ESPN NFL Draft analyst Todd McShay and ESPN senior writer John Clayton. Cosell calls any Tebow talk regarding Prescott “a waste of time.” McShay says he hasn’t heard “one negative thing” about him in Indy. Clayton is hearing a “Kirk Cousins buzz” here.

vii. ‘good food, good friends, great tradition’

Friday is an in-between day for Prescott: bench press, the Wonderlic test and more team meetings. Thursday was his media interview, while Saturday is his on-field workout.

The bench is televised by NFL Network, but there’s no way for anyone to watch it live — it’s held a level above the media room at Lucas Oil Stadium. Sometimes a loud grunt filters down when a lineman tries to fire out one last rep. The standard is 225 pounds, done as many times as possible.

I wish Prescott luck via text. He responds to say that, actually, he’s not benching. None of the QBs are. They got together and decided not to do it, union style. Saving their arms for Saturday is more important.

As luck would have it, Prescott is at the Omni with the Pro Source crew that evening. But just as I enter through one door, he’s leaving through another. He gives me a brief update and confirms our Saturday dinner before heading off for more team meetings.

Having consumed nothing more than a Clif Bar the last two nights, I decide it’s time for an actual meal and walk a few blocks to Kilroy’s, a downtown bar-and-grill that advertises “good food, good friends, great tradition.” It’s popular with Indiana Pacers fans. I belly up to the bar and ask for a menu. All I want to do is eat and decompress.

Because these things happen at the Scouting Combine, I sit next to former Tampa Bay Buccaneers general manager and current ESPN analyst Mark Dominik. Obviously, I have to ask him about Prescott.

Dominik calls him a “natural passer” — nobody ever said that about Tebow. If he were running a team right now, he says he’d take Prescott in Round 2. Unlike coaches, GMs also deal with the salary cap. A potential starting QB outside the first round is a bargain for the life of his rookie deal. Think Russell Wilson.

Even if he never develops into a starter, Dominik thinks Prescott can be a reliable backup in the NFL. That alone makes him worth a second-rounder. And if he does become The Man, “home run.”

viii. ‘it was crazy’

Oct. 11, 2014: The Bulldogs moved to 6-0 after a 38-23 victory over No. 2 Auburn. With wins the previous two weeks over then-No. 8 LSU and then-No. 6 Texas A&M, they had defeated three straight top 10 opponents.

When the polls came out, Mississippi State was No. 1 in the country for the first time in school history. Prescott and Co. had unseated defending national champion Florida State, also unbeaten but not dominating. For five glorious weeks, Hail State of all places was on top of the college football world.

In those three triumphs over SEC West rivals, Prescott threw five touchdown passes and ran for six more. He was no longer just the quarterback. The now-Heisman hopeful had become a campus-wide celebrity.

“It was crazy,” he says. “Mississippi State is not a place that’s full of history.”

Mississippi State is indeed a place that’s full of history, but most of it is dubious. The program’s all-time record was under .500. The Bulldogs hadn’t won 10 games in a season since 1999. Sylvester Croom, who was the coach before Mullen, sported a career mark of 21-38 in five years. Now the Alabamas and Ohio States were chasing them.

From students to teachers and everyone in between, nobody on campus was used to this.

“They were taking selfies (with me) on the way to class,” Prescott says. “People were bringing magazines to class, trying to get me to sign it for their little brother or their dad.

“I couldn’t even go into the student union. Stuff got crazy. Try to grab a bite to eat for two minutes, and you’re in there for 30 to an hour just signing pictures. Because you don’t want to tell those people no who support you and are there for you week in and week out.”

He was in Lost Pizza having dinner with his family when the news broke about Mississippi State being the new No. 1. The other patrons gave him a raucous ovation.

Prescott could have become a hermit. But with so many people embracing him, he felt the need to reciprocate. He was active in community service, especially when kids were involved. If the Mississippi State basketball team had a game — men or women — chances are he was in the crowd cheering.

ix. ‘good, not great’

While most reporters are contained to the media room and radio row, the Professional Football Writers of America get an opportunity to watch the Saturday drills.

The price of admission: complete a rudimentary evaluation of one player’s performance. Through this reporter pool, PFWA members can get information on all the workouts. I make a special request to be assigned Prescott, a two-birds-with-one-stone situation for me.

Prescott is part of the second group and one of eight QBs on display for key NFL decision makers. He’ll have three tries in succession at each throw, although with a different receiver every time.

The first route is a quick slant off a three-step drop. He connects on all three, with each getting progressively more accurate. Next is an out pattern about 10 yards downfield off a five-step drop. His first pass is behind the target and falls incomplete — not a good effort. But he recovers on the second and third, as both are right on the money.

Now it’s time for the deep dig over the middle, which is run at about 20 yards and requires a seven-step drop. Prescott hits his wideout in the numbers with a perfect strike all three times.

The fly pattern off a five-step drop is next. While he completes two of the three, it is his weakest series of throws. The first and third are caught but a bit underthrown — the receiver has to slow down each time. The second couldn’t have been thrown better, but the wideout drops it. He follows that up with 2-of-3 on the comeback route off another-five step drop. Again, progressively better each attempt.

By the time he’s connecting on all three of his curl patterns off a five-step drop, NFL Network analyst Kurt Warner is starting to notice. He makes a comment about Prescott looking “smooth” with his movement.

His final set of throws is the most difficult — not just for the passers, but also the route runners — as it’s a long post-corner, seven-step drop. Prescott overshoots his receiver on the first, but he comes back to complete the second and third. The second in particular was gorgeous.

From start to finish, even the throws that hit the ground are spirals in flight. All told, he was 17-of-21. He never missed two in a row. He found his target at least twice for each set of three. Additionally, for someone who has lined up exclusively in the shotgun, his footwork was crisp.

Did he help himself? It’s difficult to say. He wasn’t the best. That honor goes to Wentz, who showcased both power and touch. Stanford’s Kevin Hogan, on the other hand, looked nothing like an NFL quarterback.

I summed up my evaluation of Prescott by saying his outing was good, not great.

x. ‘a coach will fall in love with him’

If there is a better prospect here in terms of being a quality person, I’m yet to meet him. Could that be worth a bump up the board?

A good source to ask is Mike Mayock of NFL Network, one of the league’s foremost authorities on the draft. The grand finale in the media room every year at the Scouting Combine is when Mayock takes the podium for a Q&A. He is arguably the best quote in town, even coming off seven hours of live TV coverage.

So I ask him: The personal conduct policy is talked about in the NFL as much as ever these days. How much can that alone help a prospect like Dak Prescott, who might be the highest-character kid in the whole draft?

“If there’s anything I’ve seen in the last 10 or 15 years, it’s that no matter how much we tighten up the personal conduct policy, the more talent you have, the more chances you get. And that’s just the way it is, unfortunately, in all pro sports. I wish we had a way where we could reward the good-character kids at a higher level more quickly. Unfortunately, those kids get less opportunities and they have to do their jobs more quickly and efficiently than the other guys that have more talent.”

In other words, being a devil can hurt you more than being an angel can help you. Sad, but true.

There goes @15_DakP (@HailStateFB)! #NFLCombine https://t.co/fqIReWLi2d

— NFL (@NFL) February 27, 2016

Nevertheless, Mayock does see a lot of positives in Prescott:

“He’s basically one of those middle-round quarterbacks. There are teams that are going to want to work with him. He’s got height, weight. He’s got some arm strength. What he did in the state of Mississippi to galvanize that team in that state I thought was special. What happens with those kind of guys is a quarterback coach or two will fall in love with a kid. It’s not going to make him a first-rounder because he’s a great-character kid, but a coach will fall in love with him and they’ll draft him.”

Translation: He’s not Tebow. But he’s also not Goff, Wentz or Lynch in terms of pure arm talent.

xi. ‘world famous shrimp cocktail’

St. Elmo Steak House is an Indianapolis institution. No trip to the Scouting Combine is complete without dining there once. A collection of executives, coaches and scouts congregates nightly.

The only reservation I could get for Saturday — despite calling a week in advance — was ten o’clock, so that’s when I’m supposed to meet Prescott. I’m half expecting a late text with his regrets. I walk in the door at nine-fifty-nine. He arrives at exactly ten.

After making our way to the table, the server comes to take our drink order. I defer to Prescott to see which direction he’ll lean. Does he want a beer to relax after a stressful week? No, he’s good with water. Respectfully, I say the same.

This city is known for two things: the Indy 500 on Memorial Day weekend and the world famous shrimp cocktail at St. Elmo. The sauce features just as much horseradish — shockingly big chunks of the stuff — as ketchup. It’s not unusual for a patron to violently cough in the middle of the dining room. A Louisiana boy that grew up surrounded by cajun and creole cooking, Prescott goes for it. He’s impressed.

When our steaks arrive, I pick up my knife and fork. Prescott, however, bows his head to pray. Admittedly, it catches me off guard.

I may not be someone who prays, but I’ve seen people pray. Periodically you can tell when somebody is just going through the motions — muscle memory, perhaps. That’s not the sense I got from Prescott during his moment of reflection. It was only a few seconds. To me, it felt like a few minutes. My guess is he was thinking about his mother. But I’ll never know. It would’ve been rude to ask.

While he eats his 20-ounce bone-in ribeye, medium-rare, I ask him about making NFL money. He has no plans for a watch that doubles as a helipad or a closet full of Air Jordans. He already got a new truck. He’s good.

Prescott agrees with my assessment of his passing performance: good, not great. He rehashes the entire session almost throw for throw. As for the various runs and jumps, he finishes in the top half for each among quarterbacks. Just like those high school camps, he’s not about measurables.

As for his meetings, nothing caught Prescott off guard. There were no ridiculous questions that you sometimes hear about.

He does share one interesting story, though: He met at length with a quarterbacks coach from the NFC, despite the team already having a young, established No. 1. According to Prescott, the coach was only meeting with him to establish a relationship for the future — he anticipated getting fired next year. Maybe the two could work together elsewhere one day.

So where does he think he’s headed? Prescott says two clubs are showing him more love than others, even way back at the Senior Bowl last month. One is in the AFC South, the other the NFC East.

We only had two conversations of any duration, first on the phone before coming to Indy and now at dinner. After enduring four days of intrusive medical exams, repetitive team interviews and exhaustive physical testing, his attitude is remarkably unchanged — not too high, not too low.

Once we walk out the door, Prescott gives me the proverbial handshake and one-arm hug combo. I search for a cab on Illinois Street. He’s off to see a movie.

John Crist is an award-winning contributor to Saturday Down South.