The NFL’s best defense in the regular season won the NFL’s postseason. The Seattle Seahawks ranked first in the league with 17.2 points allowed per game during their division-winning regular season. That unit ranked second in the NFL in yards per play allowed and led all defenses in rushing average against. In Year 2 under the 38-year-old Mike Macdonald — a former defensive coordinator brought in to replace Pete Carroll — Seattle won the whole thing.

A few weeks prior, college football’s national championship was claimed by the Indiana Hoosiers, who, yes, deployed a Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback, but also ended the season ranked second in scoring defense and third in takeaways. Indiana was top-10 in rushing efficiency allowed, third down defense, and red zone touchdown percentage allowed.

Are we seeing the start of a defensive renaissance across both levels of football?

On the surface, it certainly seems that way.

During the 2025-26 season, 9 of the NFL’s top 10 defenses (by yards per play) made the playoffs. A 10th team (the Rams) sat at No. 11 in yards per play and earned a Wild Card spot. Three of the other 4 playoff participants were division winners. And in college football, 6 of the 12 teams that earned spots in the College Football Playoff ranked in the top 15 in EPA per play. That group included Texas Tech (No. 1), Oklahoma (No. 2), and James Madison (No. 4). The top 15 averaged 9.4 wins, with 12 of the 15 all clearing the 9-win mark.

It has long held true that defense wins championships.

Indiana’s 27 points in the national title win over Miami tied for the second-lowest point total of the season by the Hoosiers. They needed to shut down Carson Beck and the Hurricanes.

Seattle’s Super Bowl victory featured 6 sacks from the defense and 1 touchdown from the offense. The story of the game was the Seahawks putting the New England offense in a stranglehold.

But the story of the season was not that of a defensive resurgence. Trend data points in a different direction. We might be seeing the start of a leveling out, but even then, it’s too early to tell.

Here’s what the data says.

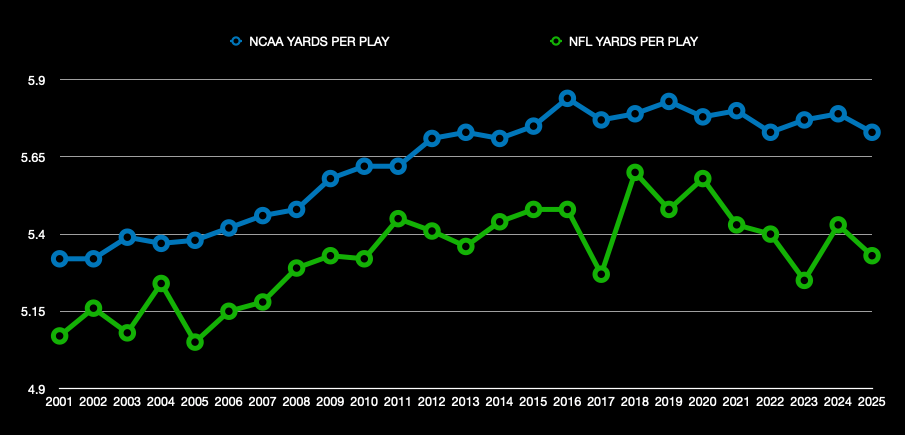

Yards per play

The most basic efficiency stat in football. What are you gaining each play? At the college level, the national FBS average peaked in 2016 at 5.84 yards per play. It has been trending down since. In the NFL, the peak performance for the modern era came in 2018, when teams averaged 5.60 yards per play. It has been trending down ever since.

Tracking toward peaks in both sports, we see a similar trend with passing averages per game. As offenses have leaned more and more on the pass in recent decades, yardage averages have climbed. Part of the dip we’re seeing now could be attributed to declining passing numbers. This past season showed the lowest pass-per-game average in the NFL since 2006. The same is true at the college level, where passes per game have been declining in each of the last 4 seasons, with 2025’s per-game average being the lowest in the FBS since the 2006 season.

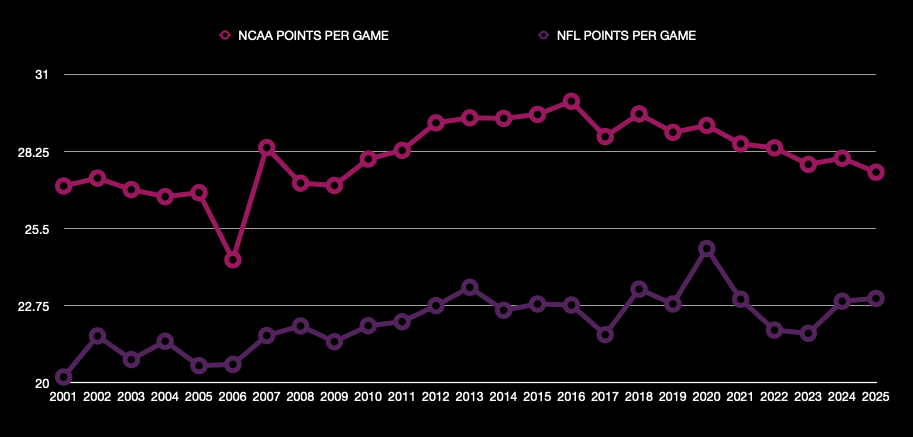

Points per game

Scoring was up year-over-year in the NFL regular season. If we ignore the 2020 season, acknowledging the randomness involved because of COVID issues, we see a scoring trend that pointed down from 2018 to 2023. Then scoring jumped in 2024, from 21.77 points per game to 22.91. It made another jump in 2025, to 23.01 — the second-highest mark in the last decade (excl. 2020).

College paints a much different picture. Scoring is trending down after peaking in 2016. FBS teams averaged 30.04 points per game that season, the highest of any year in the 21st century. Since, we’ve seen a steady decline. Teams averaged 27.5 points per game in 2025, the lowest of any season since 2009.

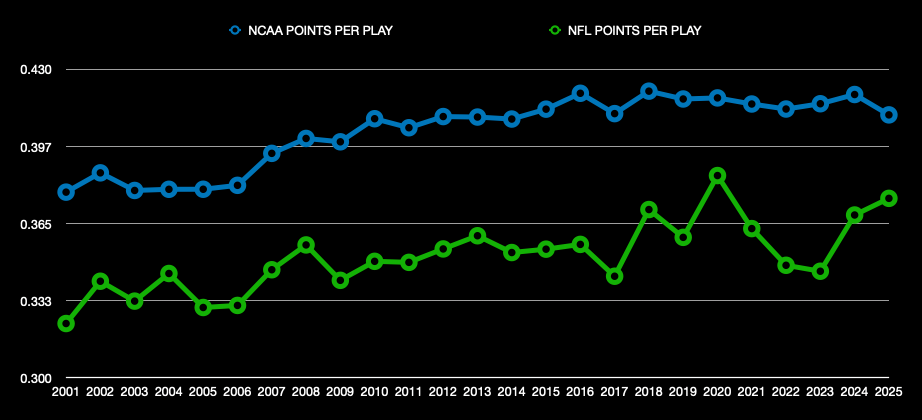

Points per play

Again, we see NFL offenses rising. And here, we see college offenses maintaining. The NFL average for PPP in 2025 (0.376) was the highest non-COVID average of the century. It also marked the third straight season of year-over-year growth.

College teams averaged 0.411 points per play, down from the previous year. Colleges peaked in 2018, with an average of 0.421 points per play. Since 2010, teams have averaged between 0.405 and 0.421 points per play every single season. Before 2010, the FBS average never cleared 0.405.

Even though scoring on the whole has seen a decline in recent years in college, what we’re seeing on a per-play basis suggests teams are getting more efficient with their opportunities. This is where the almost obsessive interest in explosive plays comes into the equation. Over the last 5 or so years, more and more coaches have talked more and more about the importance of explosive plays. Dan Lanning and Kirby Smart and Curt Cignetti all talk about that specific margin — producing more explosives than the other side — as a differentiator between winning and losing football games.

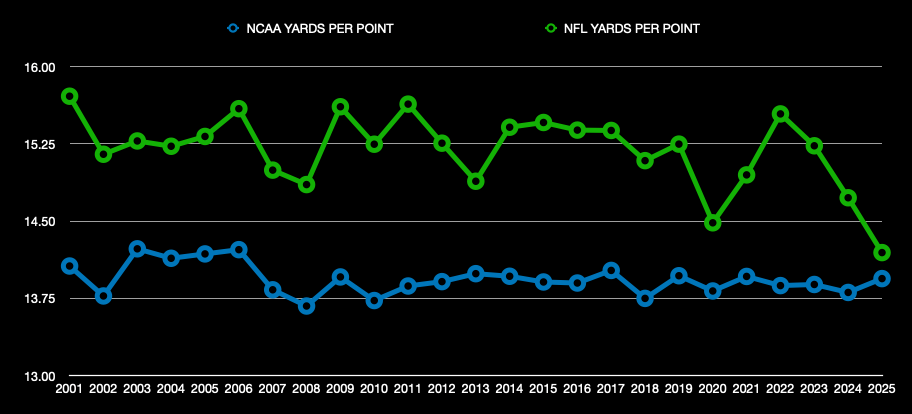

Yards per point

The best indicator of team efficiency. How many yards does it take you to score a single point? If a defense can pitch in, this number shrinks. If special teams can flip the field and win that battle, this number shrinks. If an offense can convert drives into touchdowns rather than field goals, this number shrinks. The smaller, the better.

NFL offenses had their best year of the century in this regard in 2025. Offenses averaged 14.19 yards per point, down from 14.73 the year prior, which was down from 15.23 the year before that, which was down from 15.54 the year before that. From 2001-2019, the average yards-per-point mark from an NFL offense fell below 15.0 only twice. It has happened in 3 of the last 5 seasons.

College saw a slight uptick this past season, but the 13.94 mark was still lower than the 13.96 average in 2021 and the 13.97 average in 2019. It was also still lower than the annual average in the pre-CFP era.

Plays per game

Games are shorter.

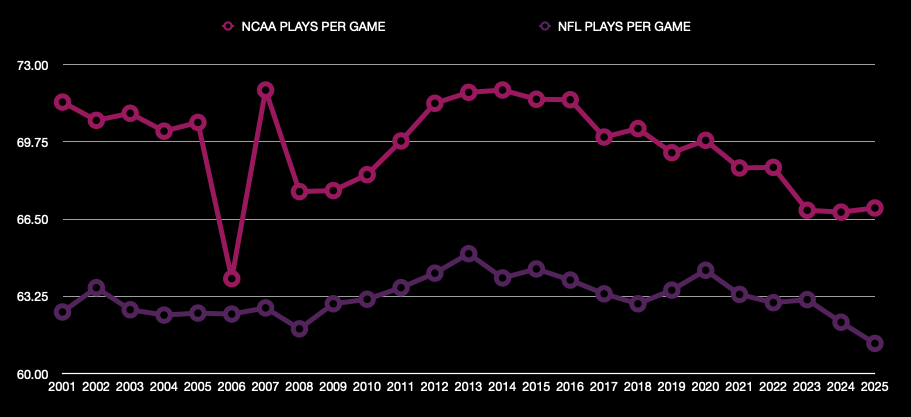

This appears to be our culprit for why scoring is trending down on a per-game basis while overall scoring efficiency isn’t showing the same kind of decline. Teams are getting fewer bites at the apple. The NFL offense averaged 61.26 plays per game in 2025, the lowest of any season this century. Teams had averaged at least 62 plays every year since 2008. Meanwhile, college offenses averaged under 67 plays per game for the third consecutive season. That happened just 1 other time in the previous 22 years.

In 2023, the NCAA changed its clock rules to move more in line with the NFL and intentionally shorten the game by allowing the game clock to continue to run even after a first down.

We’ve also seen more of a schematic shift from coaches, too. Chip Kelly’s warp-speed offenses at Oregon changed college football in a fundamental way. Teams spread out their formations and put more of an emphasis on running tempo. From 2008 through 2014, the average number of plays run by a college offense increased every single season. From 2012-16, the average held over 71 every year. It hasn’t touched 71 in a single season since.

Play counts were trending down even before the rules change took effect in 2023.

Do defenses have more advantages to press against offenses? It feels that way. Or, at the very least, defenses have more counters to what offenses are doing.

When Kelly took the sport by storm with Oregon in the late 2000s/early 2010s, he hit defenses with concepts and designs they hadn’t seen. Those tendencies then filtered up to the NFL and we saw a similar shock-and-awe period. With the proliferation of spread/up-tempo/RPO offenses, there was a flood of new ideas that crashed into defensive coaches in a relatively short amount of time.

We haven’t really seen another offensive innovation that pushed the sport to quite the same degree in the years since, giving defensive personnel time (and tape) to come up with counters.

But it seems a little too early to suggest that defenses now have the advantage over offenses. Defense wins championships. That remains true. In a one-off setting, if you can sack the opposing quarterback 6 times and produce 3 takeaways, it would take an implosion on the other side to lose. But, offenses still seem to be doing their thing.

Derek Peterson does a bit of everything, not unlike Taysom Hill. He has covered Oklahoma, Nebraska, the Pac-12, and now delivers CFB-wide content.