A CALL TO END

OVERTIME

IN COLLEGE FOOTBALL

By Marky Billson / May 16, 2016

“I am into basics and I don’t like fads” — Hank Williams Jr.

College football has always been innovative, from the invention of the plastic helmet to the 2-point conversion to the touchback on a kickoff being placed at the 25-yard-line.

Now it’s time for college football innovate again and eliminate gimmickry.

It’s time to eliminate overtime.

The current format of college football overtime gives whatever team wins a hollow victory. College football overtime is, all at once, unsafe, a glorified field goal kicking contest, a horribly flawed system in which the team that receives the ball second has a tremendous advantage, and it eliminates a factor as vital to football as blocking and tackling — field position.

A tie is a legitimate result.

Whatever comes from the above mess is not.

College football overtime is designed to give both teams equal chances for victory, but the rule fails in a manner not seen since “Plessy v. Ferguson.”

The team “batting” second effectively gets four downs while the first team on offense gets three.

The team “batting” second effectively gets four downs while the first team on offense gets three. If this isn’t enough, if the game remains tied after the first overtime period, the team that “hit” second then keeps possession to start the next period.

Previously given a huge advantage in the first overtime, this team now gets the added advantage of having their already vanquished opponent play defense for a second straight possession.

That is not football. Furthermore, Kevin Rudy of The Minitab Blog deducted in 2013 the team that “bats” last in college football overtime wins 61.5 percent of the time.

Football doesn’t need overtime. The 2-point conversion is there for any coach with guts to break ties in most late-game situations.

The reason we have overtime is the very lowbrow belief a game must not end in a tie.

Who knew the 1992 film Mr. Baseball, which otherwise lost more than $19 million at the box office, had so much influence?

The notion is absurd, and ignores a very fundamental truth: There is always a winner and a loser in a tie.

Ties created historic games, lasting memories.

The greatest headline in the history of American journalism did not come from the New York Times, Washington Post or Chicago Tribune.

Harvard Beats Yale, 29-29

The greatest headline in the history of American journalism was “HARVARD BEATS YALE, 29-29” which found its way on top of the Nov. 25, 1968 edition of the Harvard Crimson.

Go ahead. Name a better one. As Alan Schwarz wrote 16 years ago in Harvard Magazine, “DEWEY BEATS TRUMAN” is an inaccuracy. It is not a statement of wit or cleverness or even legitimate information.

Now imagine if there is overtime in 1968. The Harvard-Yale game is forgotten. No headline, no movie, no “did you know Tommy Lee Jones was a lineman for Harvard in the game?” No great tales from Calvin Hill on how Carm Cozza didn’t emphasize special teams during Yale’s practices in this era, thereby revealing how football has changed and the Elis lost their 16-point lead with less than a minute to play.

An overtime decision in Harvard’s favor would not make the game sweeter for them, and an overtime victory by Yale would seem hollow, far more than the Co-Ivy League championship the Bulldogs shared with the Crimson that year seems.

“The Game” had been decided. It did not need a gimmick to give closure.

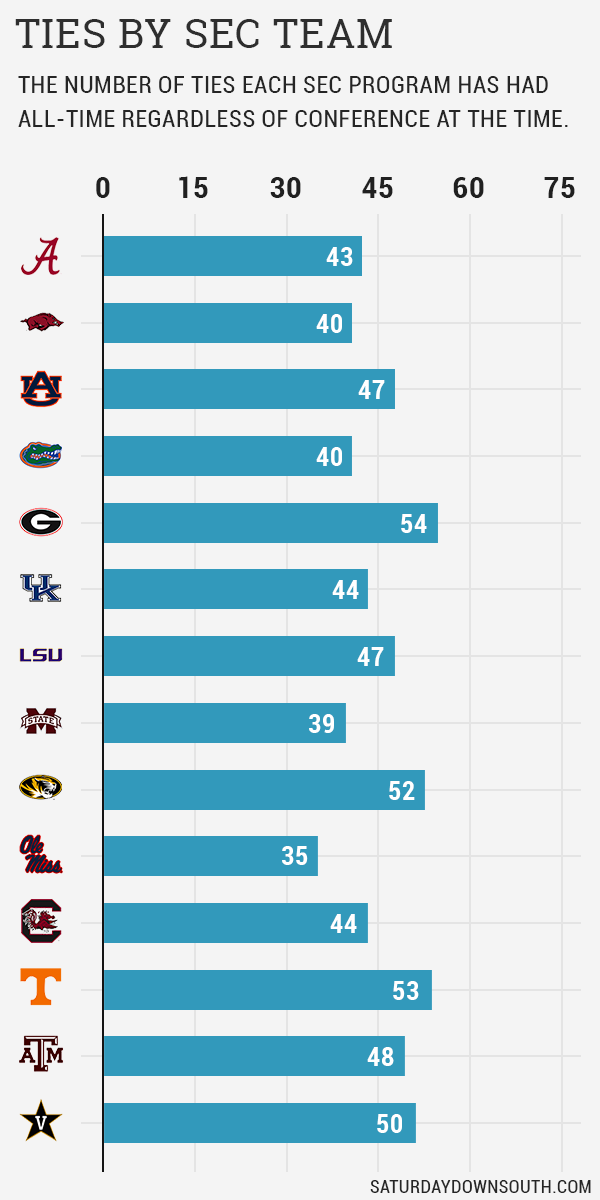

The SEC has had its share of The Games as well.

Alabama’s 17-17 tie with Tennessee in 1993 was not only a Crimson Tide victory by any standard of reasonable measurement, it ultimately resulted in the most graphic display of the Volunteers’ pain, and pettiness, in enduring three long losing streaks to the Crimson Tide since 1970.

Before the 1993 Alabama-Tennessee game, the Tide had defeated the Vols seven consecutive times. Before that, the Vols had enjoyed a four game winning streak in the rivalry from 1982-85, but that only halted an 11-year Alabama winning streak against Tennessee dating to 1970, when the series record was tied 23-23-7.

Alabama trailed, 17-9, before taking over with 1:44 remaining in the fourth quarter at their own 18-yard line with no timeouts.

Eleven plays later, quarterback Jay Barker finished an 82-yard drive by scoring a touchdown on a sneak with 21 seconds remaining. David Palmer, who had caught three passes for 44 yards in the drive, then moved to quarterback for the 2-point conversion, where he would score on a keeper off right end to even the score.

Technically, Tennessee had ended its losing streak against the Tide. What’s more, Alabama’s 28-game winning streak was over, reduced to the moniker “unbeaten streak.”

Who cared? The Vols couldn’t close the deal. What’s more, when Tennessee took over for its final possession, the Vols were content to just call running plays to run out the clock.

Today such gutlessness would be rewarded by giving the Vols a chance for victory, the very chance they were rejecting by running the ball on their final drive.

In time, Alabama forfeited the game, as they did all of their 1993 regular season victories. The Tide’s Antonio Langham, thinking he’d enter the ’93 NFL Draft before ultimately returning to college, signed with an agent after the previous season’s Sugar Bowl. When discovered, the forfeits were part of Alabama’s probation.

To this day, when one looks at Tennessee head coach Phil Fulmer’s career record, it’s strangely missing a tie. No, the Vols are more than happy to accept the hollow forfeit, even though they didn’t even lose the game on the field.

Meanwhile, conference mates South Carolina and Ole Miss accept their 1993 defeats to the Tide in their media guides.

The overtime rule in college football was adopted for the 1996 season.

The last tie in the SEC occurred when LSU and South Carolina played to a 20-20 draw on Sept. 30, 1995 at Williams-Brice Stadium.

How appropriate the last SEC tie, hopefully only to date, occurred in the state where the 1948 Wofford Terriers once tied five straight games.

And who would have ever heard of the ’48 Terriers if they hadn’t?

Furthermore, how appropriate the last tie featured a game with South Carolina? Their 14-14 tie against Wake Forest in 1945 prompted the creation of the Gator Bowl six weeks later, where the two teams met in a rematch.

That doesn’t happen today with overtime. The modern-day correlation would be the BCS title game in January 2012.

Remember how critics said LSU and Alabama meeting again in the championship had rendered the Tigers’ 9-6 overtime victory against the Crimson Tide meaningless?

It was.

If that game instead finishes in a 6-6 tie, then the championship game is the war to settle the score.

But if that game instead finishes in a 6-6 tie, then the championship game is the war to settle the score. The regular season meeting becomes not a boring game but a hard fought defensive struggle that proved Alabama and LSU truly were the two best teams of the season.

Even when Alabama wins the title game rematch 21-0, the circumstances are remembered for the ages.

Just as the January 1995 Sugar Bowl is. That game settled the 31-31 Florida-Florida State tie five weeks earlier, where the Seminoles scored four touchdowns in the fourth quarter only to meet the Gators again on Jan. 2.

Sure enough, FSU came away the victors 23-17.

Put overtime into the mix, and that year’s Sugar Bowl rematch is met with the same response the final BCS Championship Game was: “Again?”

Instead, it was a must-watch Chapter Two.

As for LSU, their 2007 national championship squad is destined to go down as one of the weakest national championship teams in history because they had the most losses of any team to finish No. 1.

But both of the Tigers’ losses occurred in overtime. Take away overtime, and LSU is an undefeated national champion, the “weakest national champion” debates can go back to 1960 Minnesota and 1990 Colorado, and the Bayou Bengals get their just deserts.

In LSU’s 1995 tie against South Carolina, the Tigers’ Sheddrick Wilson, playing with a sprained knee and ankle suffered earlier in the game, caught a 19-yard touchdown pass from Jamie Howard with 1:06 remaining. It would have been barbaric to ask Wilson to play an overtime period on top of what he had done and could have ended his career, which instead took him on a brief trip into pro football.

0-0 IS A FOOTBALL SCORE

71-63 IS NOT

If Rocky II is ever remade, here’s what won’t happen. Rocky Balboa will be a second too late getting up, and then, with both Apollo Creed and Rocky on the canvas knocked out, Mickey and Duke will be asked to slug it out for a round to decide the fight.

An absurdity. But the equally absurd football equivalent is to have the game decided by field goal kickers.

Not a kicker coming on after the offense has put him into position to win the game or the defense has come up with a turnover, mind you. That’s still a determination of field position, and if the placekicker can boot a long one through the uprights, or his teammates put him into position to win on a chip shot, more power to them.

College football overtime is: Unearned field position, offensive failure, kick. Unearned field position, offensive failure, kick

College football overtime is: Unearned field position, offensive failure, kick. Unearned field position, offensive failure, kick.

Would this really have made, say, the 1946 Army-Notre Dame scoreless tie more memorable?

That game featured the two top offenses of the day being completely shut down. Unquestionably Johnny Lujack redeeming his interception to make a touchdown saving tackle of Doc Blanchard is American sports lore, and a far better way to ultimately determine a national champion than to have Blanchard and Notre Dame’s Fred Earley decide it in a contest of 42-yard field goal attempts.

Scoreless ties don’t happen often. The last one in major college football occurred in 1983.

But as Army and Notre Dame proved, when one does happen, it becomes a game for the ages.

And it is now impossible.

Deciding the ’46 Army-Notre Dame game by a 3-0 or 6-3 score would have been as much of a crime, if not worse, as turning a 24-24 game into a 71-63 monstrosity.

Which is precisely what Arkansas and Kentucky did in 2003.

That seven overtime game was not a testament to two great offenses — despite the extra time neither quarterback threw for 330 yards or four touchdowns.

It was merely an example of two fatigued defenses unable to stop an opponent. Jared Lorenzen, the Wildcats’ 320-pound quarterback, rushed for three touchdowns in the five-hour game before finally losing the contest on a fumble.

When a 320-pound quarterback is able to extend a game scrambling for multiple touchdowns, it’s not because he’s a great runner. It’s because the defense is exhausted, the extension is flawed and, dare we say, unsafe.

Bring back the dramatic decisions

The overtime rule rewards cowardice

Nebraskans never held his boldness against him

Tom Osborne may have cost the 1983 Nebraska Cornhuskers a national championship when he went for two in the Orange Bowl against Miami, but Nebraskans never held his boldness against him.

Passive leadership wouldn’t have earned Osborne 83 percent of the vote in his 2002 Congressional run. Bold leadership did.

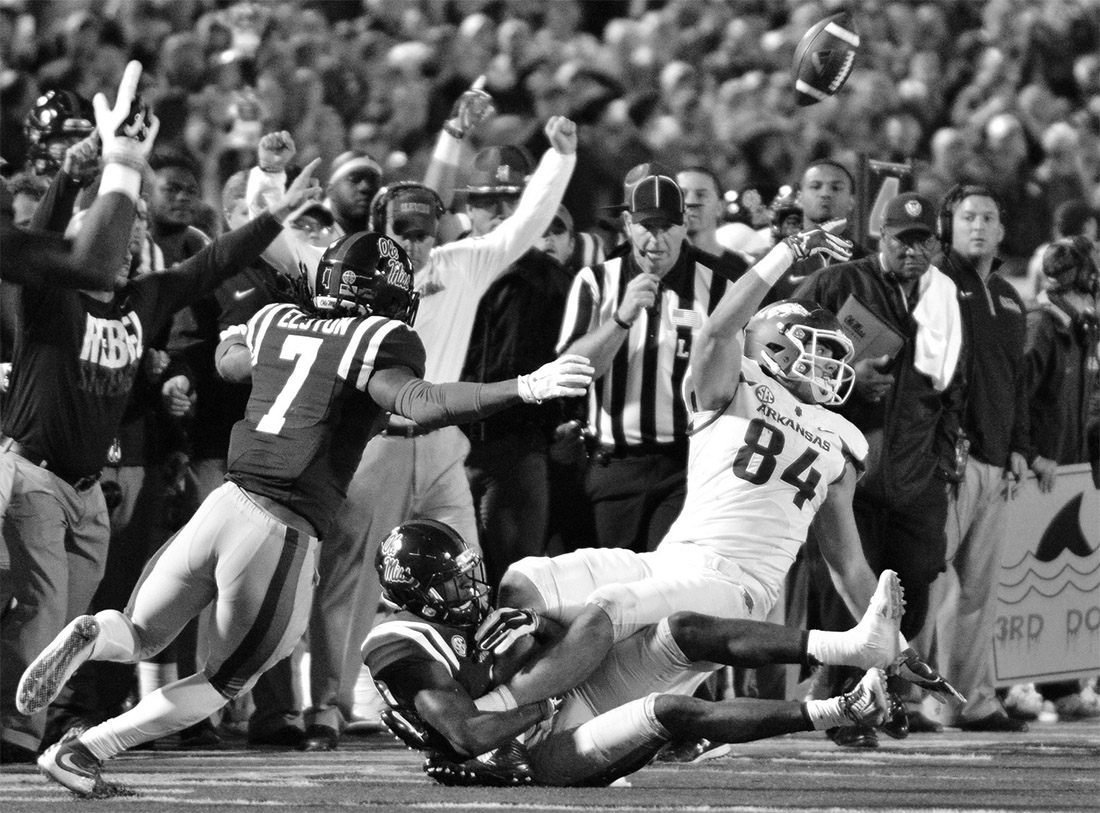

Sure, Arkansas’ 2-point conversion to beat Ole Miss 53-52 in overtime last season was exciting and nobody will ever forget the wild 4th-and-25 conversion, but why didn’t Bret Bielema make that same gutsy decision after pulling within one on a touchdown with 53 seconds left in regulation?

Instead, he kicked the extra point to force the extra period. Ultimately, only good fortune made that look like a good decision.

While there is a need for overtime in semifinal playoffs (simply adopt the sudden-death format the NFL uses), it is not needed elsewhere. For years, the NAIA had no overtime in their championship game, and four times it resulted in two teams being crowned champions.

Yes, the college football playoff was supposed to end that from happening in the FBS, but imagine the following scenario.

Your favorite team scores a touchdown in the CFP Championship Game with no time remaining to pull within a point. Your coach can kick an extra point and play for overtime.

Or, he can theorize “/SHer/” is a singer from the seventies. That he wants his team to stand alone. That “if we can’t score from the 3-yard line, we don’t deserve to win the national championship!” That, to paraphrase the lyrics of AC/DC’s Brian Johnson, he doesn’t care how much he’ll laugh when he picks up the prize.

This decision is far more delicious than any actual play ever could be. Furthermore, it would cement the coach’s and the program’s personality and reputation forever.

Kinda beats a national championship decided on a pass interference penalty, doesn’t it?

A post-game thought

Schwarz’s November 2000 Harvard Magazine article, “The Saga of a Great Headline,” uncovers the story of how “HARVARD BEATS YALE” came to be.

After exhaustive research, Schwarz discovered it was written by Crimson night editor Bill Kutik upon the recommendation of photographer Tim Carlson, who had heard the line uttered by a drunken undergraduate in the celebration on the field after the famous 1968 game.

What did Kutik, now the host and managing editor of Firing Line with Bill Kutik, think of overtime? An interview request was tweeted to him.

“Do you wear a belt and suspenders with elasticized pants?” came the reply. “My e-mail is on Linkedin, always the first place for a reporter to look.”

I no longer needed to seek out Mr. Kutik’s opinion on overtime. Clearly, the adoption of the rule was so devastating to him it had destroyed his social skills.

So please, college football, for credibility, for safety, for excitement, for strategy, and most of all, for Mr. Kutik’s sanity:

Get rid of overtime.