Comparing college sports to apartheid is inaccurate, insulting and incendiary

By John Crist

Published:

Patrick Hruby wrote a feature story last week for VICE Sports examining “racial injustice” in collegiate athletics.

He made a comparison between big-time college sports — football and men’s basketball, specifically — to apartheid, which is defined as “a policy or system of segregation or discrimination on grounds of race.”

Essentially, the argument constructed is that rich, old, white men armed with authority and influence are exploiting poor, young, black men blessed with nothing more than speed and strength. TV contracts, season tickets and merchandising sales generate billions of dollars in revenue, deepening already-deep pockets.

Meanwhile, athletes get nothing. Blood, sweat and tears aren’t worth the price of the jerseys they soil.

Is the system flawed? Absolutely. But to say that it’s exploitative is hyperbolic. To suggest that players should cease being students and start being employees is to ignore the intrinsic value of a scholarship.

More egregious, to equate college football and basketball with apartheid — or, worse, slavery — is an indignity to the people of South Africa. Apartheid was the source of decades of violence among countrymen and a trade embargo with the outside world. The Republic continues to lick its wounds a generation later.

A five-star defensive tackle on a full ride to Georgia has next to nothing in common with Nelson Mandela.

Scholarship athletes get free tuition, free room and board, free healthcare, free food and free swag, plus a (remote) chance to one day live their pro dreams. Mandela spent 27 years in prison for differing political beliefs.

Have you ever seen a player walking to class? Chances are he’s decked out head-to-toe in school-issued gear. In his pocket? iPhone. On his ears? Beats by Dre. He may not have a lot of cash in his wallet, but how many students do? Being broke — and learning to manage money — is part of life as an undergraduate.

There are plenty of middle- and upper-class kids that visit the local plasma center when they’re strapped.

The term “student-athlete” may be outdated, but these are still academic institutions first and foremost. Hruby’s feature illustrated that a miniscule 1.6 percent of college football players make it to the NFL.

Too many of them fail to graduate. Even the ones that do, oftentimes their degrees aren’t legit because they skated through school taking sham classes just to stay eligible. A high percentage major in sport management — basically studying to become athletes. It’s too much work to shoot for civil engineering.

Coaches may indeed steer players toward easy courses, but the decision to take them is ultimately theirs.

From practice to meetings and the weight room to the film room — all wrapped around a full-boat class schedule — a stunning amount of time is asked of these athletes. Dawn until dusk, they’re on the clock.

However, that’s not exclusive to the football and basketball teams. Softball players do the same juggling act, yet nobody cries for them. Additionally, softball players don’t have multi-million-dollar carrots dangling from their batting helmets. They’re almost certainly “going pro in something other than sports.”

Who is forcing kids to sign letters of intent? If the game is so hopelessly corrupt, then don’t play it.

Naturally, football or basketball may be their only chance at breaking the generational chains of poverty. Many of these young men, as opposed to the gated-community lacrosse players, don’t have a ton of options.

However, this isn’t a bait-and-switch situation. Everyone involved knows what’s expected of scholarship athletes. Despite the NCAA supposedly being as stingy as Ebenezer Scrooge — the pre-Ghost of Christmas Future version — National Signing Day is a universally joyous occasion. Recruits finally become signees.

Athletes don’t arrive on campus and only then realize that so much more is demanded of them as collegians.

Every fall, we hear about so-and-so safety from Florida being the first from his family to attend college. Such-and-such linebacker from Arkansas barely qualified academically in order to accept his scholarship.

If they weren’t football players, what exactly would they be doing with their lives? Admission standards are appreciably reduced for athletes. Education expenses impossible to cover on their own — Vanderbilt’s tuition for the 2015-16 academic year was $43,620 — are suddenly comped. Yet this is somehow a raw deal?

A scholarship athlete can potentially realize hundreds of thousands of dollars in educational value alone.

There is approximately $1.2 trillion in student-loan debt across this nation. Even white-collar earners — doctors, lawyers, etc. — usually have to dig themselves out of a deep hole before living the plush life.

College graduates have a higher chance to succeed than non-college graduates, plain and simple. For many families, putting kids through school will be their most significant expenditure. Those baseball players on travel teams at nine years old? They have parents flipping every stone to locate a scholarship one day.

A free education may pale in comparison to Alabama coach Nick Saban’s salary, but it’s far from worthless.

And even Saban can’t guarantee NFL riches. Far more players that come through his football factory will be better off with a diploma hanging on the wall than a microscopic chance to be teammates with Amari Cooper.

Hruby claims that amateurism “costs the average African-American major college football or basketball player somewhere between $500,000 to $1 million over a four-season campus career” based on not seeing a fair share of the revenue being generated by their respective sports — that’s potential nest-egg money.

But he ignored his own data — about half of these scholarship athletes aren’t black — to charge racism.

Ironically, when Hruby listed what an exploited ex-athlete might be able to do with that kind of cash down the road, following “start a business” and “buy a home” is, incredulously, “pay for a child’s education.”

That’s right. The same education he got for free as a scholarship athlete. The same education he didn’t take seriously enough when he was in school. The same education he was granted most likely for no other reason than his skill as a football or basketball player. Now, conveniently, it’s all kinds of important.

The system will never be perfect. If there’s a buck to be made, the unseemly are going to try to make it.

It’s ridiculous that the CEO of a bowl game — usually a crusty old white guy, of course — can command a seven-figure paycheck and be given pop star-level perks. After all, he has to put on one contest per year.

The schools make a fortune in gate receipts. The conferences make a fortune in rights fees. The TV networks make a fortune in advertising deals. The apparel companies make a fortune in retail sales. But just because the athletes don’t deposit a check, that doesn’t mean they’re playing for free. Far from it.

Now the fact that a football or baskeball player can’t profit off his name is indeed unfair. If an athlete can make some money on the side by signing autographs, more power to him. It may legitimize those hundred-dollar handshakes we all know are happening at every program anyway. What’s the real harm?

Instead of doing away with the popular college football video game that EA Sports used to make, use it as an opportunity to redistribute some of the wealth. If a player is listed on a roster in the game, he gets $100 — perhaps have regional covers like they do for magazines. Make the cover? Bam, $5,000 just for you.

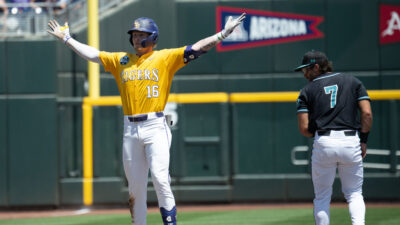

The earning potential supposedly being taken from the players is usually only an issue for the superstars. LSU running back Leonard Fournette could surely help move a lot of Chevys in Baton Rouge if a dealership wanted to hire him for commercials. That’s not the case for offensive guard Maea Teuhema.

By itself, more money is rarely the answer. Even with cost of attendance stipends now being handed out by Power 5 schools, do you really think the extra cash is always set aside for necessities? Too many college students — youngsters in general, really — prioritize tattoos over paying the electric bill.

Sports agent Don Yee is quoted in Hruby’s feature. None of his clients believe the system is “equitable.”

Well, life isn’t equitable. The sooner people figure that out, the better. Becoming a professional athlete is odds-defying, just like becoming an astronaut — and statistically about as likely. Have a backup plan.

Compare football and basketball recruits with ROTC members, who are also awarded merit-based scholarships. Football and basketball players are asked to be athletes and students simultaneously. It’s a lot of work, both mentally and physically. But for many it’s the only path to a degree, especially the underprivileged.

Members of the ROTC are asked to be students in additon to the military and officer training they receive. Like athletes, it’s a lot of work, both mentally and physically. Unlike athletes, their commitments aren’t complete once that diploma is hung. They’re obligated to years of possible in-harm’s-way service overseas.

Football and basketball players are given every advantage to be the best students they can be (tutors, special study halls, accountability and more) while also maximizing their athletic prowess — all unavailable to ordinary undergraduates. Why is it hard to put a dollar figure on the value of a scholarship? Because so much of the experience is, in a word, invaluable.

Every college campus in America is overflowing with non-athlete students that are overworked and underfed. They live in crummy dorm rooms. They work part-time jobs — maybe even full-time — around daunting class schedules. They gain experience with unpaid internships. They incur crushing amounts of student-loan debt.

These are the rules of engagement for low-income people that weren’t born with 4.4 wheels or a 6-foot-9 frame. If you ask them, scholarship players do get paid. To a run-of-the-mill criminology major, a free education and the handouts that go along with being an athlete are the equivalent of a six-figure salary.

During my time writing about sports, I’ve talked to more current and former athletes than I can remember. If you want to get a quotable answer out of an NFL player, ask him a question about his alma mater. The rivalries, the pageantry, the big-man-on-campus life — it all led to enviable pay days in the pros, too.

Never once has an athlete told me he regretted going to college. Nobody suggested he would’ve been better off driving a UPS truck straight out of high school. Not one longed for the dangerous lifestyle typically associated with the inner city. A scholarship can sometimes quite literally be a get-out-jail-free card.

Even players that don’t make it to The League benefit greatly from higher education.

It’s plausible that football will more closely resemble baseball one day, with a minor league funneling young talent directly to the parent club. Basketball already has the D-League serving a similar purpose.

Blue-chippers that don’t want to be burdened with problems like expanding their educational universe or diversifying their social interests — who wants that? — could bypass college altogether to earn a decent living as a minor leaguer. Some argue that college football is essentially a minor league minus NFL wages.

But until that time, as Hyman Roth sternly said to Michael Corleone, “This is the business we’ve chosen.”

Hruby’s title, “Four Years a Student-Athlete,” is a twist on “12 Years a Slave.” In the film, a free black man is abducted and sold into slavery. It’s a grim reminder of perhaps our country’s most shameful memory.

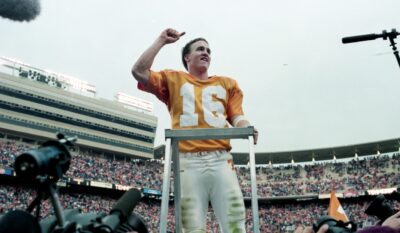

To even tangentially intimate that the plight of a college athlete is akin to a slave is reprehensible on the part of Hruby. One enthusiastically put pen to paper before firing up the fax machine — destination Knoxville. The other was ripped from his wife and kids before being beaten on a plantation in New Orleans.

Again, the system may be flawed. But it’s done way more good than bad. Nobody ever said that about slavery.

John Crist is an award-winning contributor to Saturday Down South.