First and 10: NIL isn’t the enemy. It’s the biggest threat to college football royalty

By Matt Hayes

Published:

1. I don’t want to get on a soapbox, but …

It’s time for a deep, cleansing breath, everyone.

It’s not the end of college football, or a self-inflicted death blow or any other hyperbolic nonsense thrown around by — take your pick — coaches, media and politicians.

We’re a year into state legislation that forced universities to allow players to earn money off their name, image and likeness, and already the narrative is college sports has forever changed.

All because 19-22 year olds suddenly get a piece of the action.

“Everybody is going to have to pick how they’re going to manage this,” Alabama coach Nick Saban said.

I have a suggestion: Everybody calm down.

At the end of the day, this is strictly a goods and services deal. Like any hot new product — say, a certain stationary bike that was selling at 10 times the market price because people chose to exercise alone in their basement before announcing to the world on social media they were doing so — the initial appeal gives way to healthy skepticism. Only the best products survive.

So while coaches and administrators and university presidents pontificate about the “sustainability” of the NIL system, the answer to their problems of lost power and money (more on that later) are literally in the words escaping their collective mouths.

Sustainability is in the eye of the beholder. Or the collective doling out dough.

The marketplace is the single greatest governor of all things goods and services. Always has been, always will be.

Big money boosters who have formed collectives to pay student-athletes to hawk their products won’t continue to throw bad money after good if they’re not getting the rate of return they want.

A majority of the NIL commitments are 1-year deals. Soon, they’ll all be 1-year deals — with most connected to performance clauses. Collectives (see: boosters) are not going to pay good money for a player who doesn’t produce.

Why did the the price of a certain stationary bike plummet over the past 6 months? Because the initial instigating factor (COVID) waned, and all that was left was an overpriced piece of stationary exercise equipment for those who desperately wanted out of the house, anyway.

The initial instigating factor with NIL deals is winning football games. Once collectives (again, see: boosters) see money doesn’t necessarily translate to wins, the freewheeling financial windfall for players will eventually even out.

How long will it take? It could be as short as 1 season in some cases, or as long as 2 or 3 in others. If you don’t think rate of return is critical with all collectives, you’re not thinking about how a majority of boosters within those collectives earned their money.

And more important: How they continued to build wealth (not by throwing good money after bad).

Until then, coaches and administrators are going to have to deal with the reality that some players care more about what they can get before they commit to play, instead of what they get after. And they’ll use it as a negotiating tool (see: a free market).

“What is real and what is fiction?” LSU coach Brian Kelly said. “You could hear ‘I was offered $1.5 million to come to X school. You better get on board, or you’re not going to get me.’ Or maybe someone is helping them say that. There are a lot of moving parts here. We have to get past this early part. It’s up to coaches to make good decisions and stick to what you believe in.”

And it’s up to players to smartly get everything they can, while they can. Not unlike any other negotiation in a free marketplace.

If you don’t think that’s fair, ask former Alabama linebacker Dylan Moses about fair. Ask him about the millions he could’ve made in the NFL were it not for the debilitating knee injury he sustained while playing for the Tide.

Or ask Marcus Lattimore. Or Michael Munoz. Or Rawleigh Williams III.

2. The underlying factor

The fuel of a free market is competition. Without competition, there are monopolies.

This is Economics, 101.

This is college football — and why so many at the top are panicking and responding with such outlandish (and blatantly false) statements.

The world revolves around money and power. Why would college football be any different?

It should come as no surprise then that Saban and Georgia coach Kirby Smart both have said the current NIL market is “unsustainable.”

Or that Ohio State coach Ryan Day proclaimed late last week while meeting with about 100 members of the Columbus football community — and I can’t believe I’m writing this — that the Buckeyes’ football program needs $13 million a year to put together a roster that could compete at the highest level.

You see where this is going, right?

The heavyweights of the sport — Alabama, Georgia, Ohio State, Clemson — have become the most outspoken about the explosion of NIL (to be fair, many others have, too) because NIL is the great equalizer. Again, think in terms of pure economics, and the impact of a free marketplace.

When monopolies exist (see: Alabama, Georgia, Clemson, Ohio State), the market doesn’t set the price for goods and services. The seller sets the price.

Those 4 programs (and Oklahoma) have benefited most without a free market in the Playoff era. They win big, win championships, and the elite of high school football and the elite of the transfer portal flock to their campuses.

While I’m not minimizing the effort and skill it takes to build programs, once you get to that point, those 5 programs sell themselves. It’s a distinct, near-monopolistic advantage.

Those 5 programs have accounted for 23 of the 32 spots taken in the 8 Playoff seasons, and 7 of the 8 national titles.

Now that NIL has entered the equation, money — above board money, at that — suddenly becomes a leading factor in roster management. Throw in the one-time free transfer gift from the NCAA, and those 5 programs have lost the power they’ve had over everyone else.

So now they complain about money.

That’s why Day is asking Columbus heavy-hitters for $13 million a year. That’s why Saban, speaking 2 weeks ago to a group in Birmingham with deep pockets, complained that Texas A&M bought every player in its No. 1-ranked recruiting class.

Now there’s competition. And competition gives other teams the opportunity to recruit better and gain ground, increasing their ability to reach the Playoff and win big.

3. Power and money, The Epilogue

No one recruits like Saban and Smart. Swinney has built a monster of an SEC program in the middle of the watered-down ACC. Day took over for Urban Meyer, and the Buckeyes are more dangerous than they’ve ever been — on the field and recruiting.

Instead of seeing big picture and focusing on what got them to the top of the mountain, those at the top are pointing to 5-star WR Luther Burden staying close to home and choosing Missouri over Georgia and Oklahoma. Or 5-star DT Travis Shaw choosing North Carolina over Georgia and Alabama.

Or 5-star OT Kiyaunta Goodwin choosing Kentucky over Alabama and Michigan. Or Texas A&M landing 8 5-star recruits in one class.

They point to a “process” that is “unsustainable” and is “bad for college football.”

This point, above all else, must be made: NIL and the one-time free transfer rule isn’t bad for college football.

It’s bad for those at the top.

As a whole, it’s more work for everyone involved on every campus. From assistant coaches and head coaches, to support staff and recruiting coordinators, to the NCAA compliance offices at every school.

And they’ll adjust — like they always do. They’ll add more support staff, change job descriptions, invent new jobs.

Year after year, season after season, coaches stress to players you can’t get too high or too low. Control what you can control.

Only the free marketplace can control NIL. Everyone breathe and have patience.

4. There are no bad guys

For the first time in more than 150 years of college football, players have power and money.

More distressing to many coaches: players have that power and money before they even arrive at college.

Somehow, high school players have turned into the heavy in this growing NIL era. Coaches can understand current players on the roster earning NIL deals.

They can’t understand the explosion of deals for players who haven’t stepped foot on campus.

“Boosters should be precluded from recruiting,” Saban said. “Including use of NIL offers prior to enrollment.”

Before we start drawing that line in the sand, understand that many of those very teenage recruits are better players than those currently on college rosters.

If college football is a merit-based world — and coach after coach subscribes to that philosophy — there should be no issue with collectives paying players who haven’t stepped foot on campus.

Shannon Snell, a former All-American guard at Florida and member of the Florida collective said, “We’re paying for a player’s ceiling.”

In that sense, there’s no difference between a current player on the roster and a player who is being recruited.

5. The Weekly Five

Five reasons a 9-game schedule is the best fit for the SEC:

1. The case for permanent opponents: 3 are better than 1. A 3-6 model with 9-game schedule is superior to a 1-7 model with 8-game schedule.

2. Texas and Texas A&M must play every year. Tennessee and Alabama, too. That doesn’t happen with an 8-game schedule.

3. Important conference games in the first month of the season.

4. The end (hopefully) of FCS games, while still (hopefully) retaining the 1 Power 5 nonconference opponent mandate.

5. The move to 9 doesn’t make it harder to get to the Playoff, it makes it easier. Better games against better teams.

6. Your tape is your résumé

An NFL scout analyzes the prospects of a draft-eligible SEC player. This week: LSU WR Kayshon Boutte.

“I feel really good about him. Speed, balance, vision, an understanding of the passing game. He’s the complete package. He tracks and locates deep throws and can highpoint. He has the extra gear to gain separation, on intermediate and deep throws. He has terrific, soft hands and doesn’t mind mixing it up. The only question I have right now — and he can change it this season — is can he win consistently in our league on the outside? He’ll be a terror in the slot, but can he prove himself on the outside and possibly move into the top 10?”

7. Powered Up

This week’s Power Poll, and one big thing: I’ve got a feeling …

1. Georgia: It won’t get any better in 2022 for the Stetson Bennett can’t win it all club (of which I was once a founding member).

2. Alabama: The struggle to run the ball last season (No.10 in the SEC) wasn’t an anomaly.

3. Texas A&M: Uncertainty on the offense line isn’t going away with new OL coach Steve Addazio.

4. Kentucky: UK could win 10 games again and still not make a dent in the SEC East.

5. Arkansas: Hogs will have a better team in 2022 — but won’t win 9 games.

6. LSU: Those who laughed at Brian Kelly’s fake southern accent will be more annoyed by how quickly he turns around the program.

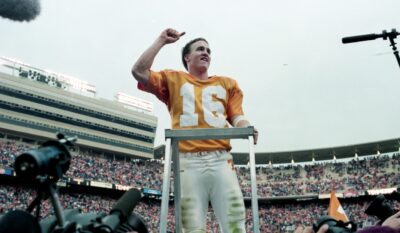

7. Tennessee: The Vols will pull off a major upset in 2022.

8. Ole Miss: Lane Kiffin has as much uncertainty at QB since his first season at Tennessee in 2009.

9. Mississippi State: A manageable first month will be overshadowed by a brutal second month.

10. South Carolina: We’ll all be talking about TE Jaheim Bell by the end of 2022.

11. Florida: If QB Anthony Richardson stays healthy, he’ll show elite talent.

12. Auburn: The Tigers will use 3 quarterbacks in 2022.

13. Missouri: QBs Tyler Macon and Brady Cook compete early, freshman Sam Horn wins the job late.

14. Vanderbilt: Vandy won’t walk away from coach Clark Lea after 2022, no matter the carnage.

8. Ask and you shall receive

Matt: Is the SEC Playoff a real thing or just leverage on the rest of college football? — Steven Profitt, Atlanta.

Steven:

There was a point in last week’s SEC spring meetings where SEC commissioner Greg Sankey was asked a similar question, and if you weren’t paying attention, the response went right over your head.

Sankey said the SEC Playoff, “wasn’t created as a threat. Wasn’t intended as a threat.”

It you’re reading that on its face, the idea is the SEC is not threatening anyone and trying to keep the peace.

That’s not the intent of that response. The SEC Playoff idea was created from “blue sky” thinking. In other words, give me all of your ideas with no limitations.

Beyond that, it “wasn’t intended as a threat” because it’s intended as an option — an option that is 100% still viable.

Sankey and the SEC presidents want college football to continue as is, with the FBS and FCS schools working together to continue to cultivate and promote the second-biggest television property in the country behind the NFL.

But if there’s more pushback on College Football Playoff expansion while discussing the next Playoff contract, and if the road is muddled again with Power 5 conferences looking out for their own interest, the SEC will simply move along to its own Playoff.

Again, that’s not a threat. That’s reality.

9. Numbers

2,825. For those who scoff at the idea of Tennessee making a significant move in 2022, consider this wildly overlooked factor from Year 1 under coach Josh Heupel.

The Vols nearly doubled their rushing yards from 2020, rushing for 2,825 yards last season. In 2020, Tennessee had 1,415 yards and averaged just 3.77 yards per carry and had 12 TDs.

In Year 1 under Heupel and his Blur Ball offense, Tennessee — with essentially the same offensive line and after losing its top 2 rushers (Eric Gray, Ty Chandler) to the transfer portal — averaged 4.9 ypc., and had 30 TDs.

Nine starters return from that offense, including QB Hendon Hooker, who last year had the best TD/INT ratio in the nation (31/3).

10. Quote to note

SEC commissioner Greg Sankey: “An 8-team Playoff is something we’d consider — with 8 at-large participants.”

Matt Hayes is a national college football writer for Saturday Down South. You can hear him daily from 12-3 p.m. on 1010XL in Jacksonville. Follow on Twitter @MattHayesCFB