The real truth about Michael Jordan, the baseball player

By Chris Wright

Published:

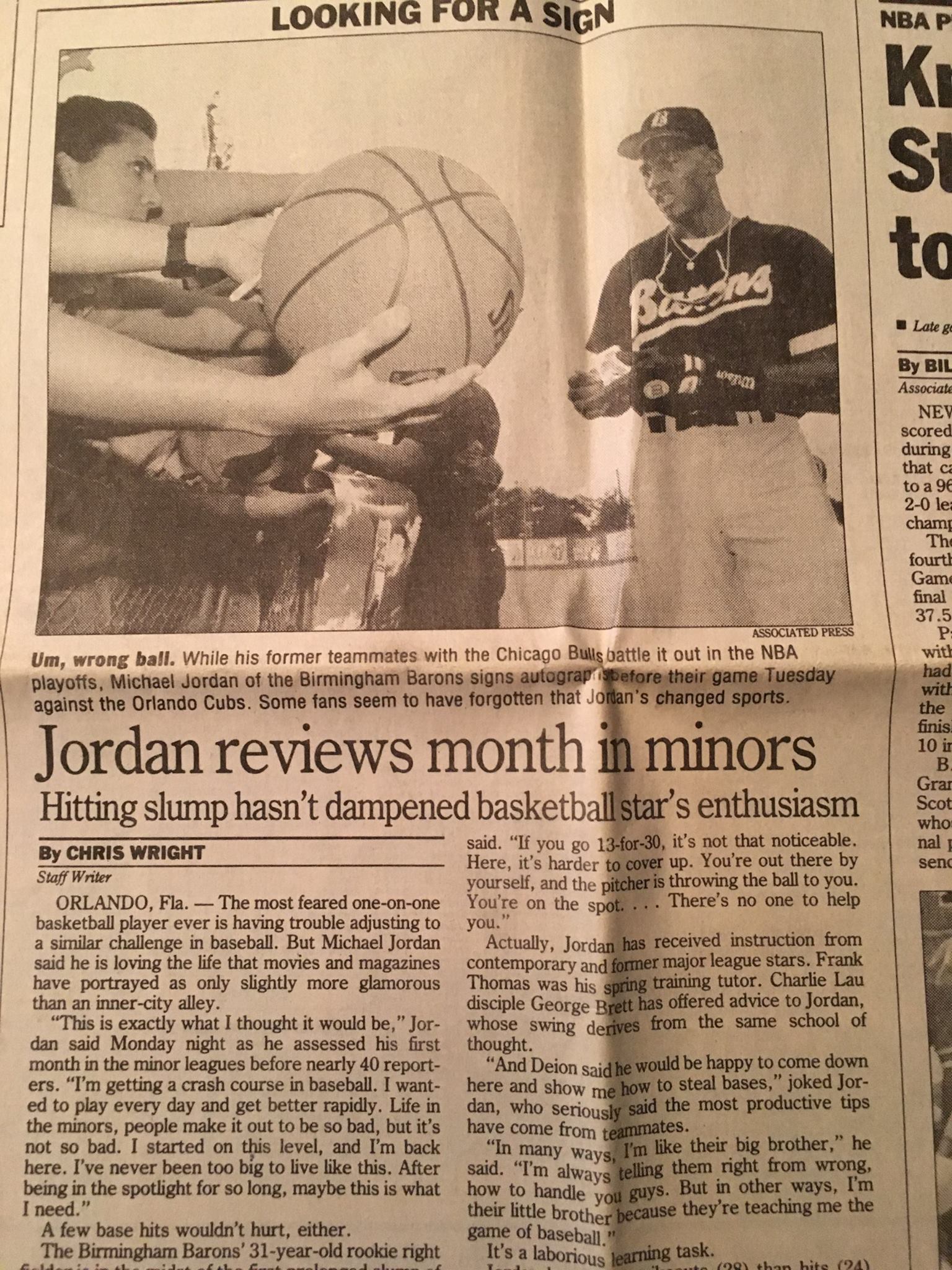

Episodes 7 and 8 of “The Last Dance” air tonight. It will touch on Michael Jordan’s sabbatical from dominating the NBA and his attempt to play professional baseball.

Much about MJ is mythical, so I’m interested to see how his stint with the Birmingham Barons is portrayed. I’ve seen a few stories this week that suggested Jordan could have developed into a Major League Baseball player.

I’ve also seen a few thousand or so minor league players, can’t-miss prospects to classic overachievers, and can confidently say: Michael Jordan had as much chance of legitimately making it to the major leagues as Craig Ehlo did in stopping him in the Eastern Conference playoffs.

As a baseball player, Jordan was Ehlo, and pitchers couldn’t wait until he stepped into the batter’s box. They attacked him. They inflicted all of the pain.

At the time, I was a sports writer at Jordan’s hometown newspaper, the Wilmington Star-News. Wilmington most certainly had a major league prospect, but his name was Trot Nixon. I was still a year from joining the staff at Baseball America, but after watching Brien Taylor and Nixon overlap over the course of 5 years, it became easy to recognize major league ability from ordinary hopefuls, even those blessed with 40-inch verticals.

When Jordan announced he was going to play baseball, I wrote that he wouldn’t hit .200. It wasn’t simply a knock on Jordan, who was 31 and hadn’t played baseball since his teenage years. It was acknowledging how impossible baseball is even for the game’s best.

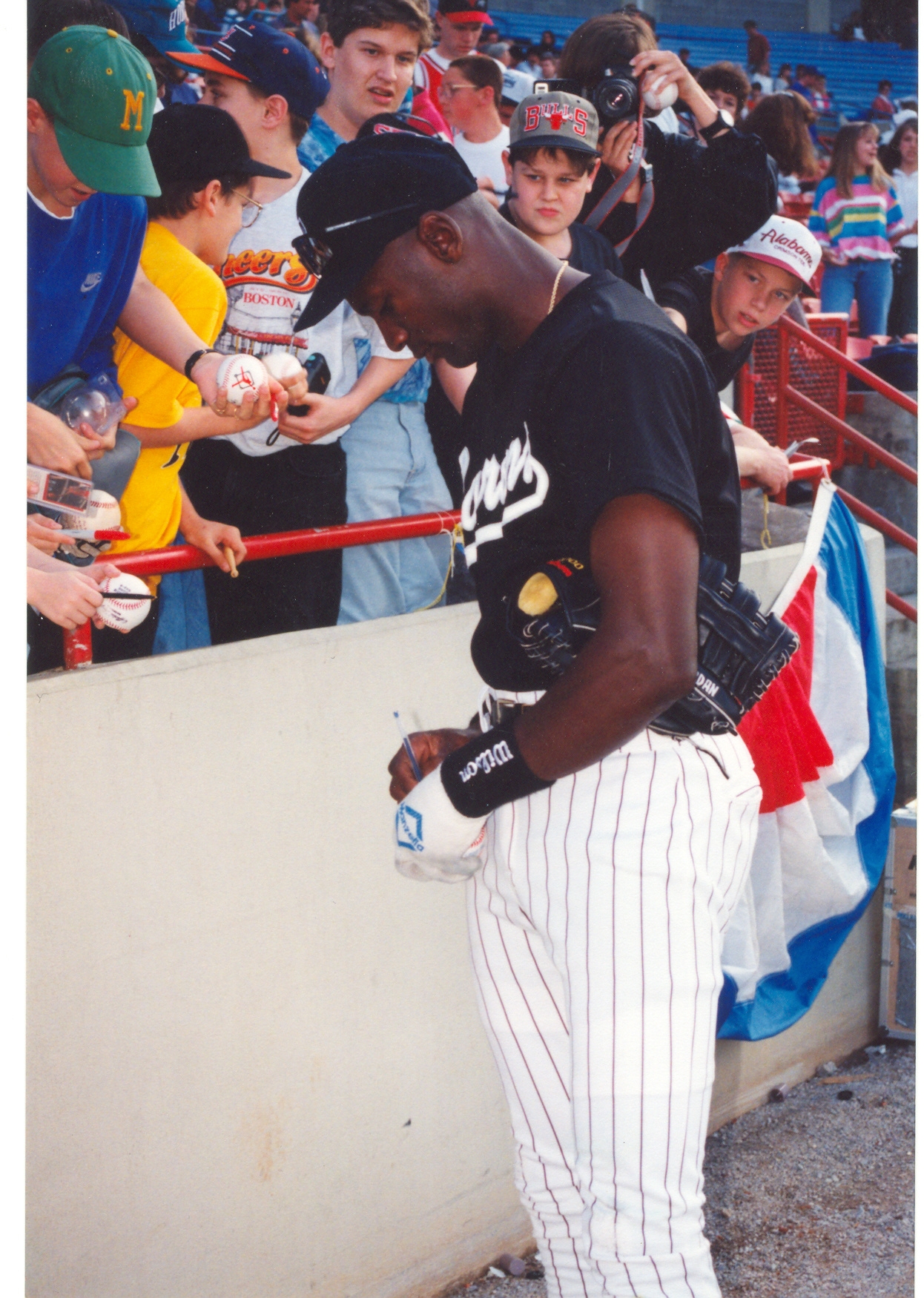

That summer, I covered probably a dozen or so of Jordan’s games.

I saw him early in the season. I saw him in the middle of the season. And I saw him at the tail end.

I saw him in Jacksonville and Orlando. I saw him in early April in Zebulon, N.C., when he got 2 hits one night, another hit the next, and 2 more the next. Turns out, that was his best 3-game stretch of the season. He left his home state hitting .333, a number that made my friends all too happy to remind me about. Ah, those Wright/wrong jokes never get old. A week later, the average had dropped to .300, and it continued in the wrong direction the rest of the season.

So, yes, in the summer of 1994, I saw the best of him … and the rest of him.

This is where you might expect to hear about the progress and, had he stuck with it, how he was on his way. His teammates and coaches, including Terry Francona, raved about him. They told me how hard he worked, how eager he was to learn. Michael brought more to the Barons than just the fabled bus.

I’m sure you’ll hear some of that tonight. The promise and potential. That the baseball skills were beginning to blossom. The routes to fly balls became straighter, faster. The line drives sounded louder. The box scores included more crooked numbers in the right places. If only he would have stayed with it …

That’s not what happened.

There is a clear line, though invisible, between hitting a baseball and attacking a baseball.

Professional hitters attack the baseball. Early in counts, they’re perfectly comfortable identifying and taking less desirable strikes, waiting instead for a pitch they can punish.

Michael, no matter when or where I saw him, always looked like a guy just trying to put the ball in play. The traditional numbers — the .202 batting average and .266 slugging average — exposed his greatest challenge and spawned the question I asked him several times that summer.

“Are you closer to recognizing your pitch and being able to attack it?”

Always glass 99.5% full, he typically answered yes. The results said no.

Michael never learned to drive the baseball, in part because he never learned which pitch he could drive. He was, in every way, behind the curve. Part of that was his body. Tall and rangy, his strike zone was immense. Pitchers were unafraid of his power, so they rarely nibbled. They attacked. They wanted to hang 3 Ks on him like he hung 30 on just about everybody every night in the NBA. He struck out 114 times that summer, almost once per game. Only 3 players in the Southern League struck out more. One was future Heisman Trophy award winner Chris Weinke, who still had a better year but ultimately realized he, too, was better in another sport.

The fact is, Jordan had 11 extra-base hits in his final 69 games. Sure, all 3 of his home runs came in that stretch, but he still had more multi-strikeout games than multi-hit games.

That’s not progress. That’s proof.

When Tim Tebow announced he was going to try baseball, I made the point that Tebow had discernible baseball skills that Jordan did not. Neither was particularly adept in the field — Jordan made 11 errors in right field — but Tebow at least had a plan at the plate. He was going to try to mash his way to the majors.

Jordan’s plan was to make contact and run. To will his way to first base, then eventually home and maybe, just maybe, all the way to Comiskey Park. Just like he willed his way past the Pistons.

Baseball doesn’t work that way.

But there’s no stopping Mike. Just like his dad said, the best way to motivate Mike is to tell him he can’t do something.

The most memorable at-bat I saw him take was against the Mudcats, back home in North Carolina.

It was early July, a typical sweltry summer afternoon that made you appreciate domes. The Barons and Mudcats were playing a doubleheader and, as usual, the ballpark was packed. It was Jordan’s first trip back since early April. His batting average had slipped below .200. The 0-fers were becoming more common, more painful. The drain of the season and reality of the challenge were never more clear.

Behind in the count, yet again, he hit a 2-hopper to shortstop. Belt-high, a Sunday hop on a sultry Saturday night. Anybody who has ever hit that ball knows from the moment of contact it’s an easy out. It’s the type of ground ball that major leaguers get benched for not running out because, you know, why bother?

Jordan damn near beat it out.

No, he wasn’t very good, but he never, ever, ever quit. Not that anybody from North Carolina needed a reminder of his “competition problem,” but he provided another example that night.

By late July, Jordan arrived in Jacksonville hitting .186. It had been more than a month since he saw his batting average start with a “.2” in consecutive games.

Friends again mentioned the column I had written before the season, where I stated Jordan wouldn’t hit .200.

I told them it wasn’t over. Jordan didn’t win a lot of individual battles with pitchers that season. He wasn’t, by any stretch, a Major League prospect. But his effort, bloody hands and refusal to lose won me over. Without question, he was going to go down swinging.

On Aug. 23, he was hitting .195. There were 10 games left in the season. I already knew how this was going to end. The way almost every MJ story ends.

Jordan had 3 hits the next night, climbing to .200 for the first time since June 28. He closed that final week with a couple more 2-hit nights.

He hit .202.

He got me.

Cover photo courtesy of Birmingham Barons

Managing Editor

A 30-time APSE award-winning editor with previous stints at the Miami Herald, The Indianapolis Star and News & Observer, Executive Editor Chris Wright oversees editorial operations for Saturday Down South.