O’Gara: Bob Knight was ever-complicated, especially for a generation that didn’t see him fade as he should’ve

Looking back, there’s not a doubt in my mind — Bob Knight played a major role in my decision to go to Indiana University.

I wasn’t one of the thousands of high school players he recruited, nor was I someone like my aunt Megan, who attended IU when Knight was at the peak of his powers in the early 1980s. In 2008, I was a high school senior in the suburbs of Chicago who often turned on the TV and thought, “man, sign me up for 4 years of Assembly Hall.”

While I did have academic reasons for my college decision — shoutout to my eventual journalism degree — that thought wouldn’t have entered my brain if not for Knight’s impact. “In 49 states, it’s just basketball …” they said. “The Carnegie Hall of college basketball,” as Gus Johnson famously called it, wouldn’t have spoken so clearly to an out-of-state teenager if not for Knight’s 3 decades of greatness.

But on Wednesday when Knight’s family announced that he died at age 83, I realized something. Unlike so many who wrote tributes about Knight’s complex legacy, I never was even in the same building with him. I don’t have first-hand accounts of Knight because while I graduated from Indiana and covered the basketball team for the student newspaper in 2011-12, he refused to step foot on the university for 20 years after he was fired in 2000 for multiple instances of physical altercations.

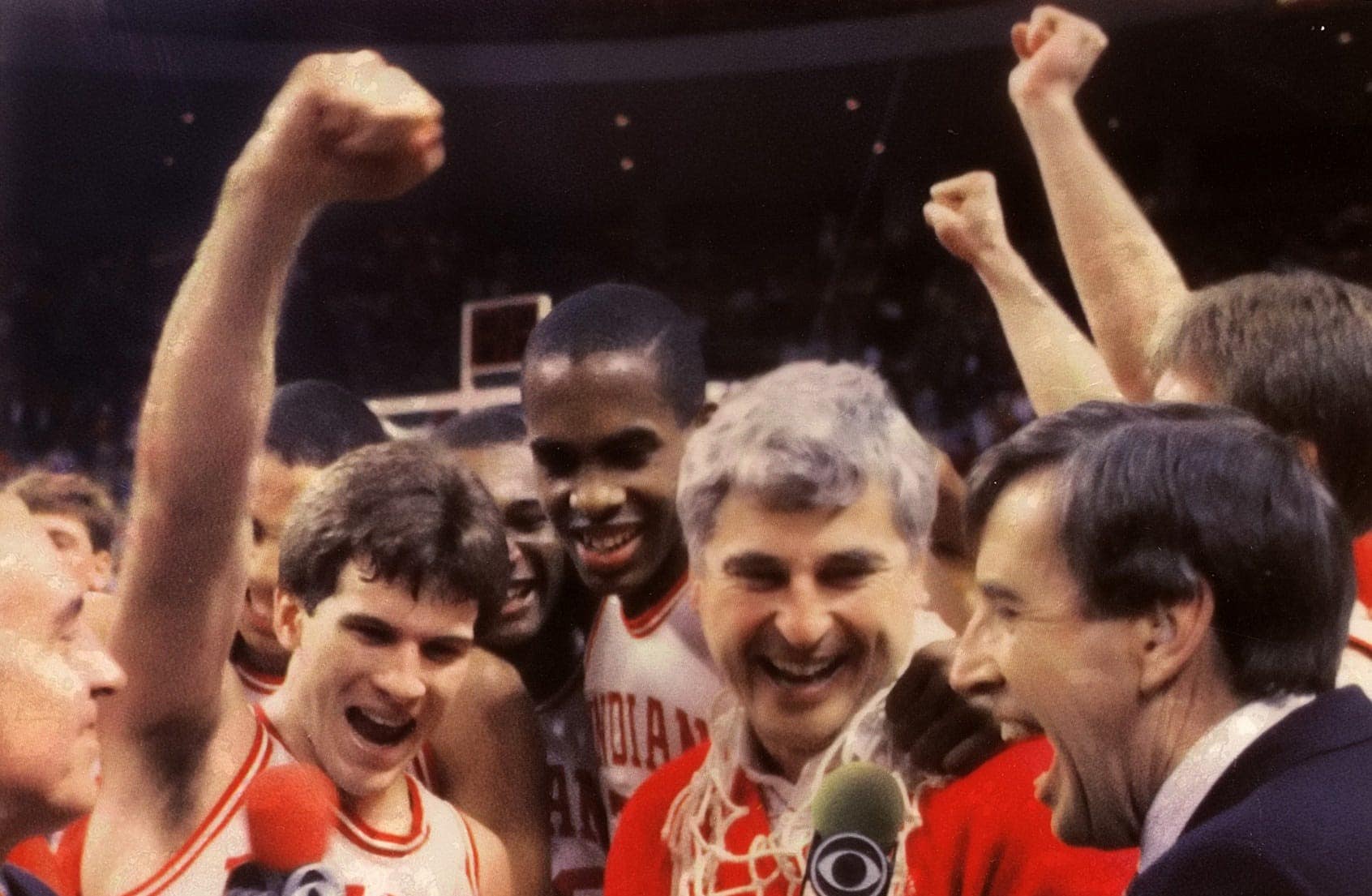

When he finally ended that in 2020, the reaction was overwhelming:

?????! ?????! ?????!

It was a special day when Bob Knight made his long-awaited return to Simon Skjodt Assembly Hall in 2020. #iubb x @IndianaMBB pic.twitter.com/n1hk2hgMl2

— Big Ten Men’s Basketball (@B1GMBBall) November 1, 2023

As memorable as that long-overdue moment was, it’s sad to think that for an entire generation — essentially anyone millennial and younger — Knight’s legacy is a complicated one that’s based on the impressions of others.

The early-to-mid-30s crowd like me was too young to remember a time when Knight dominated college basketball (his last trip past the opening weekend of the NCAA Tournament at Indiana came in 1994), yet I’m sure I’m not alone in admitting that I attended Indiana in large part because of the hoops tradition that Knight established.

Unfortunately, all our generation had were second-hand accounts of his iconic persona during our 2 decades of being shunned.

To learn about Knight, I talked to my aunt Megan about the excitement and awe she had when she got to interview Knight as a student journalist for the yearbook.

To learn about Knight, I talked to my mentor, the late Terry Hutchens about the time that the Indiana coach demanded access to his recorder after reporting injury news about a star player that he obtained while chatting with said player in the Assembly Hall parking lot.

To learn about Knight, I talked to Rece Davis, who told me a story about leaving a voicemail with Knight on Christmas Eve a few years ago, only to get a call back 10 seconds later and to Davis’ surprise, carry on a lengthy conversation like old friends do.

Knight was many things to many people. Those who spent time with him in a unique way saw that.

To learn about Knight, one can do as I did on 4 separate occasions and read “A Season on the Brink,” in which he gave author John Feinstein unprecedented access to his team during a tumultuous 1985-86 season. That book chronicled everything from Knight’s appreciation of the F-word’s versatility to his stern authoritarian ways of suspending All-American Steve Alford 1 game for posing in a sorority calendar that raised money for charity to his compassion shown to former player Landon Turner after he was paralyzed in a car accident.

One can also go back in the archives and read an all-time Sports Illustrated profile wherein the legendary Frank Deford captured everything from Knight’s peace in hunting rabbits to the reaction from his 1979 arrest for aggravated assault of a police officer while coaching Team USA at the Pan American Games in Puerto Rico.

“Bobby’s so intelligent, but he has tunnel vision.” a Midwestern coach said in the SI profile. “None of that stuff in Puerto Rico had to happen. On the contrary, he could’ve come out of there a hero. But he’s a bully, always having to put people down. Someday, I’m afraid, he’s going to be a sad old man.”

Knight left this world with that shunning of Indiana lifted. That relationship was helped even more by the return of one of his beloved former players, Mike Woodson, who was hired to be the head coach in March 2021. But for too long, Knight spoke publicly of Indiana with venom.

In 2017, Knight infamously made waves on “The Dan Patrick Show” when he and Dan Patrick had this exchange about whether he’d ever consider returning to Assembly Hall (H/T Busted Coverage):

Knight: “Well, I think I’ve always really enjoyed the fans, I always will. On my dying day, I will think about how great the fans at Indiana were. And as far as the hierarchy at Indiana University at that time, I have absolutely no respect whatsoever for those people. With that in mind, I have no interest in ever going back to that university.”

Patrick followed up: “Aren’t those people all out of there coach?”

Knight: “I hope they’re all dead.”

Patrick: “Some of them are…”

Knight: “Well, I hope the rest of them go.”

Spoken like a sad old man.

Never mind the fact that the university stood by him after his aforementioned aggravated assault arrest of a police officer and after his famous thrown chair incident during the 1985 game against Purdue. Never mind the fact that the university didn’t instantly fire Knight on the spot when CNN aired footage from practice of him choking then-IU guard Neil Reed.

(To learn about Knight and Reed, one can watch the ESPN 30 for 30 “The Last Days Of Knight.”)

On his dying day, I can’t help but wonder if Knight had wished that he had taken a page out of the playbook of a few SEC football coaches.

Steve Spurrier didn’t leave Florida on totally mutual terms, yet he still represents the Gators as an ambassador. Mark Richt was fired by Georgia in 2015 after 15 years in Athens, yet just 6 years later, he was decked out in UGA gear at Lucas Oil Stadium to cheer on the Dawgs as they finally won their first national title in 41 years. Gene Chizik was fired at Auburn 2 years after winning a national title, yet he never moved his family because he wanted to stay in that community.

Of course, no 2 situations are exactly the same. Pride impacts people in different ways. With Knight, unfortunately, it drove and kept him away.

While Knight impacted more people than any of us likely ever will, his soured relationship with the university prevented him from making an even greater impact on the community and the state that he once called home. The ball was always in Knight’s court, which was fitting for the master of a motion-style offense that was ahead of its time in the 20th century.

For someone that I neither met nor even witnessed at his best, it feels strange to look back at Knight’s impact on my life. If he had never arrived in Bloomington, I can’t say with certainty that I would’ve attended Indiana, where I met my wife and started my career. Plenty of 21st century IU graduates would tell you the same thing.

Some of them were probably there that day at Assembly Hall in 2020 when Knight got a standing ovation that was 20 years in the making. Others like myself probably watched from home with a bittersweet feeling as a tearful Knight waved to the capacity crowd.

It’s a shame that it took so long for Knight to stop being a sad old man.

Connor O'Gara is the senior national columnist for Saturday Down South. He's a member of the Football Writers Association of America. After spending his entire life living in B1G country, he moved to the South in 2015.