Noel Mazzone is a football lifer and one of the most open coaches in the game. His relationship with his new boss Kevin Sumlin dates to their days as position coaches at Minnesota and the two took strong leadership roles at the much heralded “one-back” clinic.

As a mentor at the clinic originally run by Mike Price at Washington State, Mazzone’s footballing philosophy evolved and was shaped by radical coaches like Dana Holgerson and Mike Leach.

Mazzone has coached at every level, and in a 10-month span starting in 2008 went from being a position coach with the New York Jets, to the coordinator of a high school in North Carolina, and ultimately landing as the play-caller for Arizona State. He has coached all over, with stops at Minnesota, Ole Miss, Oregon State, TCU, NC State, Auburn, and most recently, a four-year stint as offensive coordinator at UCLA.

He now finds himself entering the malaise at College Station. After the hangover of Johnny Football, the transfers of multiple quarterbacks and the firing of Jake Spavital, Sumlin has turned to his old friend Mazzone to steady the ship and rebuild an explosive offense that first put himself, and then A&M, on the map.

The Philosophy: Keep It Simple

Mazzone calls his offense the “N-Zone” and its philosophy is straight forward: Be fast, play in space, be balanced, attack and keep it simple. It often mirrors modern NBA basketball in theory: pace and space.

His idea is to have the quarterback act as point guard, spread the ball around, get the ball to his best offensive weapons in space with favorable one-on-one matchups, and do so with a quick tempo and as little communication as possible.

The Erhadt-Perkins offense

The Erhadt-Perkins offense is one of the three principle offenses run across football, alongside the West Coast and Air Coryell.The offensive philosophy is built upon simplifying verbiage, asking skill position players to focus solely on their role, and it allows the offense to run a no-huddle attack more efficiently.

It’s different from the West Coast offense, which uses elongated verbiage to deliver a play call from a huddle, detailing everyone’s individual assignment, the protection of the play and often is very wordy (particularly at the highest level). For example, “Brown Right F Short 2 Jet Flanker Drive” details each players assignment, and the pass protection.

To deliver this kind of detailed play, the offense must be in a huddle.

The Erhardt-Perkins system strips away the verbiage and instead will use a single word, number or sign as a play call e.g. “Alpha.”

In this system, everyone knows their individual assignment based on the one-word call, and the quarterback is the one tasked with knowing everyone’s assignment.

Boiling the system down to a word, number or sign, allows the offense to get the call in quicker, call the play without being in a huddle, and gives the quarterback more time to diagnose the defense at the line of scrimmage.

Like most spread attacks, it is best described as “conceptual.” All spread offenses find roots from the Erhadt-Perkins offense that has swept through all levels of football and has been run most prominently by the New England Patriots in the NFL and by college football’s most explosive spread-option offenses, most notably Auburn and Oregon.

Unlike thick west-coast offensive playbooks, conceptual offenses focus on concepts, limit the verbiage, and shift play calls from an elongated meeting in a huddle to a word, number, hand signal or Kermit the frog cardboard sign.

The system is used by all spread attacks and allows coaches like Mazzone to simplify offenses; focusing on around 18-20 concepts dressed up in different formations/alignments.

In a conceptual offense each personnel grouping dictates a player’s role. Each player is charged with knowing their responsibility for each concept, and where they line up is dictated by whomever is in the personnel package. This style of offense asks skill position talent to learn 18-20 things, rather than hundreds, and makes it incredibly easy for players, particularly at the college level, to learn the playbook as quickly as possible with limited practice time.

Everyone knows their individual role, and the quarterback knows everyone’s role. The ease of the play calls, and speed of learning the limited concepts allows them to concentrate on execution, perfect each concept, and run an electric no-huddle offense at a break-neck speed.

Mazzone loves to keep things simple and is a big believer in “don’t change the play, change the presentation” proudly proclaiming, “I ran the same four plays the entire second half” after UCLA’s 20-17 win over Texas in 2014.

He will limit the offense to around 18 concepts, with around 50 or so plays on his weekly call sheet, with each concept dressed up from multiple formations, with some pre-snap motions and shift.

He will gladly run the same inside-zone run concept four or five times in a row from multiple formations with motion players sprinkled in to add some disguise and force defensive communication.

By definition, conceptual offenses are simpler and indeed, the concepts Mazzone runs are simple and traditional. Flick through one of his playbooks and you will find nothing revolutionary, but a nice combination of traditional rhythm throws; quick outs, slants/flats, curl/flats, hitch/seam, combined with more exotic RPO (run-pass options) and packaged play concepts. There’s also a number of screen plays, as well as some of the key features of a down the field air raid offense.

Playing simple leads to the most crucial part: Play fast.

Each year at UCLA, Mazzone’s offense got quicker and ripped off more plays. In contrast, the Aggies went in the opposite direction. In 2015, led by a true freshman quarterback, UCLA finished 30th in the nation in adjusted pace and 23rd in plays per game. Texas A&M finished 33rd and 26th, respectively.

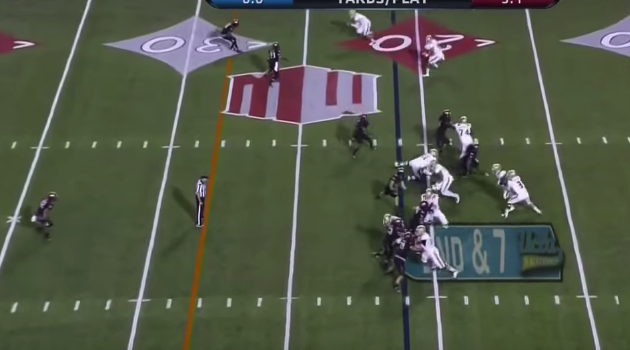

There are two variations of no-huddle attacks: a “check with me” system, in which you’ll see the offense sprint to the line, line up and turn to the sideline for the call. In those offenses, the entire offensive staff is diagnosing the defensive front, checking coverage tendencies, and using as much time as possible to get the offense into the best possible call.

The potential failure of that system is coaches can’t legislate for their right tackle being beaten by a superior pass-rusher. They can spend an unnecessary amount of time trying to call the perfect play, only to be beaten by better talent.

For this reason, Mazzone prefers the second kind — “attack” or “lightning” no-huddle offenses. These offenses like to dictate the play and tempo to the defense, rather than playing defense against themselves. They line up and snap the ball every 15-18 seconds, and run their plays, defense be damned. They wear down a defense physically and mentally, and allow coaches to better sequence their plays.

To Mazzone, playing fast doesn’t just mean lining up and snapping the ball as quickly as possible. He wants the best and quickest athletes on the field at all times and wants to get the ball in their hands as quickly as possible.

During the 2014 season UCLA ran screen plays an astonishing 33 percent of the time as Mazzone forced the ball into space on the perimeter.

Problem Solving

One key issue with an attack no-huddle offense is getting unfavorable matchups or bad one-on-one situations. For an offense built on a one-vs-one philosophy, that can sometimes give the defense a better matchup.

To combat that, like most modern offenses, Mazzone has incorporated a number of run-pass options (RPOs) and packaged plays. He’s looking for a problem-solver at quarterback and looking to solve problems for the quarterback with defined pre- and post-snap reads.

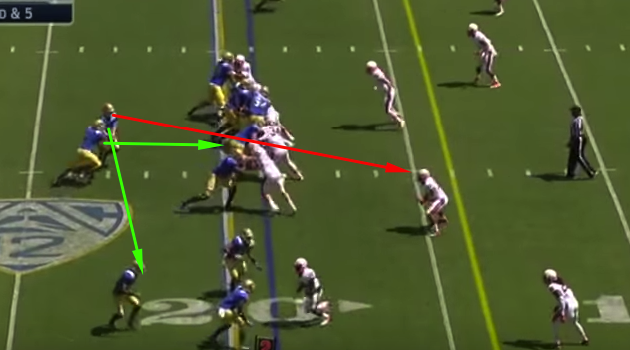

The most common and easy to define RPOs are those post-snap. The offensive line run blocks, receivers run routes, the quarterback sticks the ball in the belly of the running back, reads a key linebacker, and like a traditional read-option play, he hands off to the back or pulls the ball out and throws to a receiver.

The beauty of RPOs is that defenses can theoretically never be right; play the run and we’ll throw, play the pass and we’ll hand off.

Mazzone gives post-snap options, usually a screen pass, on almost all inside run plays. They are a safety valve and allow the quarterback to identify matchups and prevent negative plays without having to audibly change the play or slow the tempo.

RPOs have taken over offensive football, and like all great offensive minds, Mazzone had added them throughout his playbook. The defense cannot win. The offensive line is blocking as though it’s a run, the running back believes he’s getting the ball, so the defense plays run and the quarterback rips the ball out and throws it to an open receiver. Typically the ball is out of the quarterback’s hand before a lineman could, in theory, get too far downfield and draw a penalty.

While post-snap RPOs are deadly to defenses, they also create the opportunity to confuse quarterbacks by bluffing or disguising coverages and creating chances for offensive confusion and turnovers. Mazzone combats this as much as possible by also including a number of simple pre-snap RPOs.

Mostly, pre-snap RPOs are as simple as reading a front and opting to hand off or throw a screen rather than reading a key defender. But Mazzone will also package multiple pass plays in one call rather than a run-pass option.

He will combine a rhythm dropback concept like his infamous “snag” concept on the frontside of a play, and tag a screen pass on the backside.

Here, the quarterback will read the unblocked Mike linebacker. If he shows pressure the quarterback drops and throws the screen. If the linebackers turns into coverage the quarterback reads the “snag.”

On “snag” concepts, only the quarterback and coordinator know where everybody else will be. The receivers and running backs don’t adjust or read the coverage; they run their route. Based on the read, the quarterback knows where to go.

Mazzone will work a number of these three man concepts to one side of the field, but rather than the likes of Baylor, which does little to nothing on the backside, he will tag on a secondary play to avoid being predictable.

Keeping the defense off balance is also a responsibility of the line, and Mazzone likes to get creative upfront by using multiple blocking assignments within the same concept to keep the defense guessing.

He will call designed pass plays (without an option) but the line will block for a run, to give the impression of a tagged on run play. Although a lot of this is window dressing, it is greatly effective and a large reason, despite a limited number of actual concepts, each individual play can appear different based on the differing alignments, RPOs, motions, shifts and hybrid blocking assignments.

All of this has propelled Mazzone’s well-known offense to consistently rank in the top 25 in the nation, and his offenses will consistently be toward the top-end of the “explosive plays” category.

Challenge Vertically

Air Raid vs. The Spread

The Air Raid system is a pass-heavy offense that spreads the field as wide as possible, including wider splits among the offensive lineman.

Air Raid offenses traditionally throw the ball 65 percent of the time, and are repetitive in their play calling, running a small number of concepts from many different formations.

The spread offense uses similar principles to spread the defense out and widen the field, but was initially designed to be more of a running offense and has continued to be so under the likes of Chip Kelly and Gus Malzahn. The idea is spread the field with multiple receiver sets, and clear out the box to generate one-on-one matchups for the running back when running the ball, or one-on-one match ups for receiving weapons when throwing the ball.

Each coach running the offense will have their own twist in terms of concepts, formations and the variety of plays that they run, but the Spread is more balanced and the Air Raid is more pass-centric.

A lot of Mazzone’s playbook is perimeter based or designed in the box — getting the ball out quickly in space, quick-decision RPOs and an inside-zone running game. But sprinkled throughout are still elements that made him so popular among classic Air Raid coaches, including Sumlin, Mike Leach and Hal Mumme.

Many of his dropback concepts are hi-low reads that Texas A&M ran constantly under former OC’s Kliff Kingsbury and Spavital. They are another simplified pre-snap decision: “If corner A moves here, throw there, if he moves here, throw there,” and so on and forth.

Air Raid coaches rely on these plays, and they have been on display since Sumlin arrived at A&M. Mazzone will look to stretch defenses horizontally, force them to defend the entire width of the field and squeeze down on constraint before taking a big shot downfield.

Mazzone also considers the running game part of the vertical attack and believes it’s a misnomer that spread teams are built like “Air Raid” schools and should throw at all times. He wants his backs to get north-to-south, and by spreading the field they are given one-on-one matchups in the box. If they win it will generate a big chunk play.

“The spread offense was designed back in the day in order to run the football,” Mazzone told ESPN.com. “If I spread the defense out of there and only have to block five people up front to run it as opposed to blocking seven or eight, I like my odds better.”

At UCLA, Mazzone’s offenses were balanced. Though a lot of that is based on the defensive front, and where the fourth rusher is coming from, running the ball remained a big emphasis. In his four years, UCLA running backs averaged 5.0 yards per carry in 2015, 4.9 in 2014, 4.5 in 2013 and 4.5 in 2012. As a group they improved each year and had their best year when operating a system with a prototypical drop-back passer.

Think Players, Not Plays

Though a lot of what Mazzone does is interesting football theory, he readily admits that he subscribes to the belief that schemes are beautiful and all, but matchups and players win games.

“I try to create space for playmakers,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “I’m going to get you the ball where all you’ve got to do is beat one guy man to man. I do that, then it’s up to you.”

He pushes the ball to his best playmakers and strikes a nice balance between the run and pass to get the most out of his most explosive players. He will manufacture touches for the best athletes, be it jet sweeps, screens or force feeding one receiver until the defense adjusts to stop him.

The Fit

Mazzone’s fit in College Station appears to be ideal. Not only does his philosophy fit perfectly with the head coaches, it is a continuation/evolution of what the Aggies have run for the past few years.

He walked in the door with a more explosive group of receivers than the one he left in California with Christian Kirk, Josh Reynolds, Speedy Noil and Ricky Seals-Joins all dynamic playmakers.

How well Trevor Knight plays quarterback and acts as the point guard will be the most interesting question. In his final year at UCLA, Mazzone turned his offense over to Josh Rosen, a true freshman.

Rosen, a phenom, at times out-thought the simplified offense. UCLA head coach Jim Mora agreed by moving on from Mazzone and announcing that the Bruins will move to a more “pro-style” and complex offense to get the best out of Rosen. At A&M, there’s nothing like Rosen.

Knight will run the show. He is a threat with his legs and has a good enough arm to challenge defenses vertically. How he copes on rhythm dropbacks and post-snap reads will be the key to his success.

Beyond that, Mazzone’s style has already impacted Aggies recruiting. The de-commitment of Tate Martell was as much about dysfunction at A&M as it was that he simply didn’t fit in Mazzone’s offense. While a dual-threat quarterback can expand RPO plays to modern-age triple-option plays, Mazzone will always look for an accurate and quick decision-maker over a player with great wheels.

The Takeaway

Mazzone doesn’t do anything radical, and he’s no revolutionary, but what he does is highly successful.

He feeds off his players and feeds the best ones. His system is malleable enough to shape it toward his best athletes. It sticks to traditional principles but marries them to a new-age hyper-speed tempo.

Success at A&M, like everywhere, will be based upon who is executing the system rather than the system itself, and the wonderful part about Mazzone is he is one of the rare ones who not only acknowledges that, but genuinely believes it.

Oliver Connolly is the editor-in-chief of TheReadOptional.com and a football columnist. He’s a former recruiting advisor for Western Michigan University, a contributor to SI Draft research, a college football writer for Saturday Down South, and a member of the Pro Football Writers of America.