The last Cowboy: Texas A&M’s R.C. Slocum and the long trip home

By Al Blanton

Published:

The Shine Box

BRYAN, Texas — Deep in the land of the Brazos, past the lightless towns and the ranches claimed vigorously by their hard iron gates, an old cowboy is rising. It is morning in Texas, the sun bright and harsh. R.C. Slocum saddles a barstool at the business end of a kitchen counter, stares at a kinglike spread of scrambled eggs, bacon, and the best coffee cake you ever tasted. Slocum stretches a napkin across his lap and begins to devour his plate. Across breakfast, the winningest head football coach in Texas A&M history jumps into stories as if squatted beside a campfire under a starry night. Swatting his face with a napkin, Slocum tells tales of Darrell Royal, Emory Bellard and Spike Dykes — “the funniest guy in the world” — and the time he walked up to a podium, trembling, to give his testimony in front hundreds at First Baptist Church in Dallas.

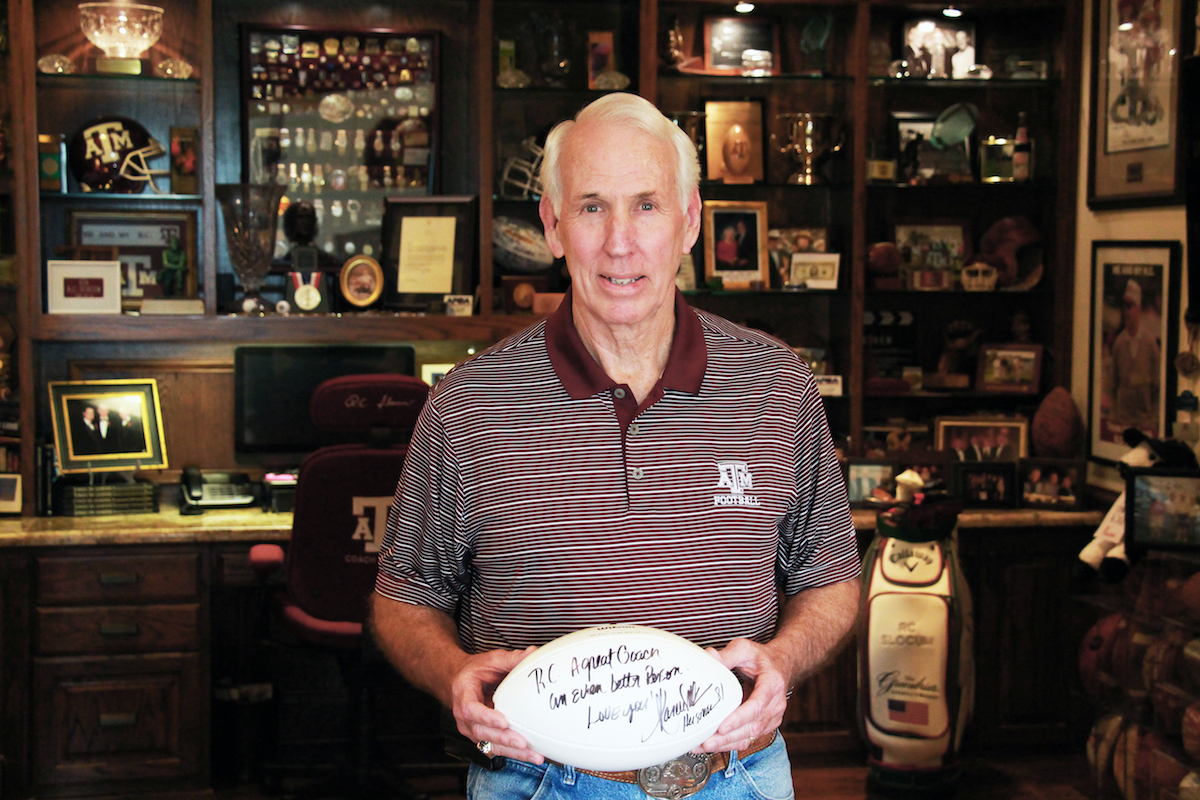

Gripping a large coffee, Slocum finishes breakfast and retreats to his Aggie room. He slouches into a leather recliner, kicking a leg over the arm of the chair. This semi-religious place (dubbed jokingly by his wife as his “I Love Me” room), is as strong a coach’s lair as there is, dripping with relics from Slocum’s long and thorough life: encased footballs, posters, prestigious awards (the most coveted being the Horatio Alger honor), bowl game watches, miniature sculptures, helmets, and a personalized golf bag and swivel chair.

Pictures of Slocum with an assortment of powerful Texans — including billionaires, heads of state, and old football chums — are scattered throughout the room, on walls. Probably the last thing you’d notice is an inelegant wooden box, pushed discreetly against one wall. At first glance, the box appears to have taken on the identity of a small magazine rack, but a closer look reveals an old shoeshine box.

“The single most important thing in my life was that I grew up in a Christian home,” Slocum told SDS.

Slocum’s story, meandering like a Texas river, begins in Orange, a shipyard town resting just inside the Louisiana border. Richard Copeland Slocum grew up in the projects — a grid of duplexes built by the federal government called the Riverside Addition. To help his family, young R.C. took to entrepreneurship, enterprising as a shoeshine boy, a sacker at a local supermarket and a paperboy. Pedaling a used Schwinn, R.C. weaved through the duplex sidewalks, yelling “Or-ANGE! Lead-ER!” before slinging copies onto lawns, damp and manicured. Weekends were spent on his knees, buffing loafers to a high shine at a barbershop (he initially charged 15 cents per shine, but inflation beckoned a quarter, his pocket fat with silver by day’s end) or praying at the church altar.

“The single most important thing in my life was that I grew up in a Christian home,” Slocum told SDS.

These principles — faith and work — set the plumb line for the rest of his life and helped him to get back to Middle C when he hit the wrong notes.

During this time, R.C. also made his first foray into the world of cowboys. Behind the barbershop, horse riders would tie their ponies to a hitching post, where R.C. learned to saddle and water them. Later, he would graduate to parading thoroughfares in the venerable Orange County “Sheriff’s Posse Rodeo,” donning a kerchief and two-tone snap-button Western shirt.

“I was just beaming with pride,” Slocum said.

Perhaps he could have pursued the cowboy life had the bride of football not emerged in the seventh grade, when a coach pulled him aside and asked, “How come you’re not playing football?” Against his parents’ wishes, R.C. tried out and, making the squad, commenced a football life that has never ceased.

What struck him about the sport were the decent men who had chosen coaching as a profession. “They were good men who cared about me,” Slocum told SDS. “I loved my coaches.”

A Way Out

Nearly everyone Slocum knew was somehow connected to the shipyards or refineries, and he saw education as a way out of this severe life. At Stark High School, he made All-District at end under coach Ted Jeffries and garnered several scholarship offers. He eventually signed with McNeese State in nearby Lake Charles, La.

A four-year letterman at McNeese from 1964-67, Slocum platooned on both sides of the ball, playing end on offense and linebacker on defense. By the end of his tenure, he set school records for receiving and was named Most Valuable Lineman.

Each summer, Slocum returned to Orange, where he labored where labor was available: in the shipyards and refineries, chipping slag off of wells. Brutal work. When he daydreamed, he entertained thoughts of law school, but the impact of his coaches and a subsequent job offer eventually killed any cravings for a life among statutes. While Slocum was taking graduate courses, the Lake Charles High School head coach phoned him about an assistant coaching position. “The head coach said, ‘I gotta know something. I don’t have much time,'” Slocum recalls. “I said, ‘I’ll take it.'”

In addition to coaching, Slocum also taught three world history classes at Lake Charles and attended night school to finish his graduate degree. Although he thoroughly enjoyed high school, Slocum pined to be in the college ranks, and a meeting with destiny occurred two springs later.

In early June, Don Breaux, who had preceded Slocum at McNeese State and was now an assistant at Arkansas under Frank Broyles, returned to Lake Charles and asked Slocum to join him on a fishing excursion. “Man I’ve got to get in college coaching,” Slocum submitted between casts. “You’ve got to help me, Don. I’ll go anywhere.”

Breaux had introduced Slocum to several Kansas State assistants at a coaching clinic that spring, and as fate had it, when Breaux learned of a position opening at KSU later that summer, he reminded them of his friend.

Slocum was soon contacted by KSU assistant Don Powell, who first had to receive approval from head coach Vince Gibson before giving the go-ahead. But Slocum never received a call.

“I waited and waited until I couldn’t stand it anymore,” Slocum said. “So I called K-State.”

“It’s all set,” Powell assured.

With no particular promise of salary, Slocum packed his bags for Manhattan, Kansas, to become a graduate assistant under Gibson, a Birmingham (Ala.) native and former assistant under Bobby Bowden at South Georgia College. Although Slocum brought home only $125/month ($75 of which went to renting an apartment), his enterprising days in Orange had prepared him well. He was debt-free and an expert on scrounging.

Slocum coached for two seasons at K-State and watched the fiery Gibson intently, soaking up knowledge. “Vince was hard-working and hard-charging,” Slocum said. “He wasn’t opposed to jumping all over you. Work ethic was so important.”

Before Gibson, Kansas State had been a perennial doormat, but the wins slowly began to trickle in on Gibson’s watch. In 1969 and ’70, the Wildcats defeated Oklahoma in consecutive seasons.

During his youth, Slocum’s first college game to attend was the annual Texas-Texas A&M contest, held on Thanksgiving weekend. “It was the biggest game in the country to me,” Slocum said. Agog at the western-proud spectacle, the humble youth drank in the pageantry: the fight songs, the bonfires, the corps of cadets, the clashing hues of burnt orange and maroon. When choosing his allegiance, Slocum leaned more heavily toward A&M, falling under the influence of Mr. Homer Stark, an Orange resident who was an Aggie. So when A&M and head coach Emory Bellard (prounounced “bell-ARD”) called in the spring of 1971, Slocum knew where he wanted to be.

In the end, it was Slocum who pursued Bellard. Hearing of Bellard’s hiring, the young assistant at Kansas State plotted to shoehorn his way into the Aggies program when opportunity presented itself over Christmas break. Leaving from Orange at 3:30 a.m. on the day Bellard was scheduled to assume the reins as head coach, Slocum made a gutsy, 3 1/2-hour drive to College Station, where he greeted Bellard’s secretary at 8 a.m.

“Ma’am, I’d like to speak with Coach Bellard,” he said.

Flabbergasted, the secretary emphatically submitted that this was “not a good day,” but, sensing passion in Slocum’s eyes (and a bit more salesmanship), she let him in. After finagling his way into the lobby, Slocum sat in a hallway chair, where he waited for hours. Finally, around 1:30 p.m. the secretary stuck her head in the doorway and said, “He has a little time at 4 o’clock.”

Five minutes was all Slocum needed. Within that small time frame, Slocum established suitable rapport and was hired two days after Christmas.

Bellard, a former assistant at Texas who once hatched the wishbone offense when the Longhorns were negotiating offensive doldrums, was a stark contrast to the seething skipper in Manhattan. For Slocum, discipleship under Bellard harkened to those idyllic days in Orange; he was a player’s coach who instilled core values into the lives of his apostles, such that today, Slocum repeats the commandments of Bellardism as if they were holy rites. “He stressed that there was never a time to curse a player or put your hands on him,” Slocum said. “He said, ‘First of all, they ought to be too big and strong to put their hands on. They’re somebody else’s son. These are our guys. Some mother and father entrusted their prized possession to us. Work ’em as hard as you want. Be demanding, but never demeaning.’ Those were guidelines I kept throughout my career.”

Slocum also sat in on a meeting where Bellard was asked about recruiting black players.

“Coach, how many black players can we sign?” one assistant asked.

“We can sign as many as we can, if they’re good players and good people,” Bellard thundered. “‘Cause it’s the right thing to do. Y’all just recruit ’em and sign ’em!”

That same year, Bellard signed nine African-Americans to scholarship, many of whom went on to careers in the NFL (later as head coach, Slocum signed players of all colors and nationalities, including Tongans and Vietnamese).

As an assistant at A&M from 1972-1980, Slocum witnessed the rise and fall of the Aggie Empire. The year Slocum arrived in College Station, the team went 3-8 and finished the year tied for seventh in the Southwest Conference. Four years later, the Aggies were 10-2 and conference champions. From 1974-77, the Aggies notched a 36-11 mark and had pulled even with Texas (defeating them two out of four years).

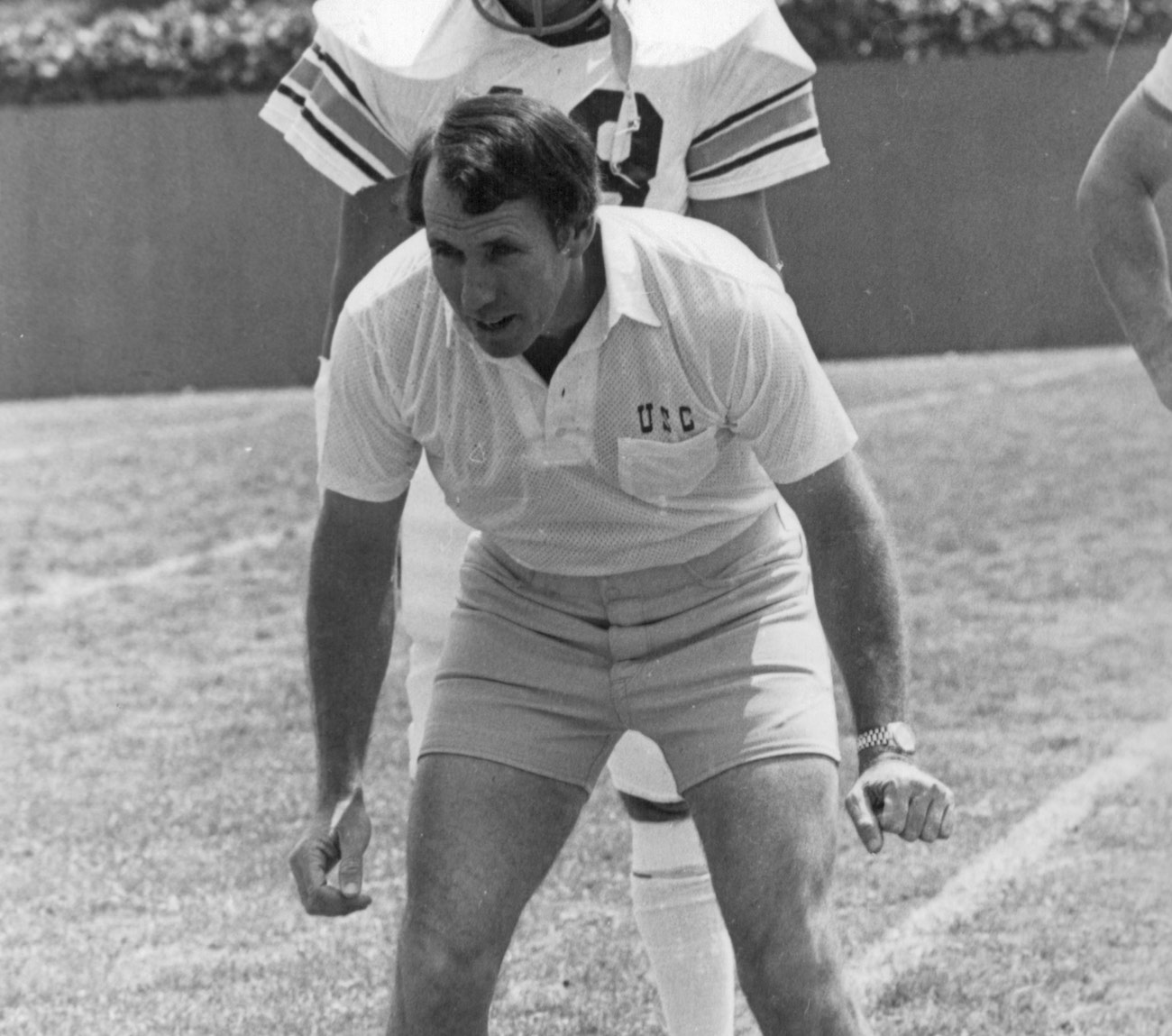

But after two close losses to start the 1978 season, Bellard surprised everyone by tendering his resignation. Assistant Tom Wilson took over and Slocum was promoted to defensive coordinator. It wasn’t long before Slocum sensed a dust storm building in College Station, and after two mediocre years, he escaped to Southern California in the spring of 1981.

The Signed Football

“It’s a long way from Orange County, Texas to Orange County, California,” a Los Angeles newspaper headline read. Like a sore thumb, the bumpkin from east Texas stood out in the City of Angels. The bright lights, the Hollywood stars, the Athens-like coliseum was like nothing Slocum had ever seen — “The first Saturday I was there, I said, ‘There’s the Fonz!'”

Installed as the defensive coordinator under coach John Robinson, three years removed from a UPI National Championship, Slocum took over a Trojans defense reeling from the exodus of Ronnie Lott to the NFL the year previous. On the opposite side of the ball, the offense enjoyed the luxury of a standout tailback by the name of Marcus Allen.

In Robinson, Slocum found a teacher, a coach who loved technique and instructing players down to the minutiae. He found a competitor, ravenous for the big game, taking on all comers and, no matter the foe, expecting to emerge victorious. Robinson was a swashbuckler of a coach, as big as L.A.

The warrior-general also proved adept at surrounding himself with talented lieutenants. As a Trojan, Slocum worked alongside a proud stable of assistants, including Norv Turner, Hudson Houck, and Gil Haskell — all of whom would achieve success in the NFL.

“It was a lot of glitter for a boy from Orange, Texas.”

Coaching at USC was no ordinary gig — it was Valhalla. Players were treated like royalty. Slocum, serving as the Friday night chaperone, would transport the team to Beverly Hills or Hollywood to dine before catching a flick at a private screening at Universal Pictures. These were just some of the perks of being in the USC fraternity. During the week it wasn’t uncommon for movie stars and former players to show up at practice.

“O.J. was around all the time,” Slocum said of Simpson, USC’s 1968 Heisman Trophy winner. “He’d come out to practice, shake hands with everybody. He was bigger than life, a fun guy to be around. He was really liked by all of the teammates and coaches.”

“It was a lot of glitter for a boy from Orange, Texas.”

That year, USC went 9-3 and finished tied for second in the Pac-10 with Arizona State. Besting his predecessor Simpson, Allen galloped for 2,427 yards and became the first back to gain over 2,000 yards in a season. In December of that year, he too was awarded the Heisman Trophy.

Slocum’s defense, led by linebacker Chip Banks, allowed only 14.2 points per game and achieved success by employing the mantra “you’ve got to scratch where you itch,” meaning where there’s a problem, fix it.

While Slocum “loved his time” in L.A., he quietly promised that if the Good Lord ever saw fit to bring him back to Texas, he’d go and never leave. Traveling the pretzel-like freeways, he longed for the prairies. Touring Beverly Hills, he longed for the Brazos.

As it turned out, his wish was granted more quickly than expected. Slocum recalls receiving a phone call on a Saturday night in January as he was enjoying a recruiting dinner at Julie’s restaurant. On the other end of the line was Jackie Sherrill, the head football coach at Pitt, who was mulling the job at Texas A&M.

“He asked me, ‘Is A&M a good job?'” Slocum recalled. “I said, ‘It’s a great job.'”

History between the two men had been brief; Slocum and Sherrill had crossed paths at various coaching conventions, but they were not personal friends. Sherrill wanted to gauge Slocum’s interest in returning to the state of Texas as his defensive coordinator.

“I’d be very interested,” Slocum told Sherrill. “But I need time.”

Time Sherrill did not have, and he informed Slocum that a decision needed to be made by morning.

Reflectively, Slocum sees this moment where two distinct roads diverged. Had he stayed at USC, he might have assumed the head coaching position after Robinson left for the L.A. Rams that spring, or perhaps at another school on the West Coast. In the end, the hard pull of Texas was too strong to overcome. “My roots were in east Texas,” Slocum said. “I told him I’d take the job.”

Although Slocum was at USC for only one year, he maintained a lifelong relationship with many of the players. A football resting in the “I Love Me” room reads:

“RC a great coach an even better person. Love you!!! Marcus Allen Heisman 81”

Me and My RC Poster

In the winter of 1982, Slocum and Sherrill descended on College Station like paratroops intent on liberating the program from mediocrity. They came from different coasts and they were different men, but across seven years, they helped rebuild the Texas A&M program into a formidable contender, not simply in the Southwest Conference, but again on the national scene. Together, they won three consecutive SWC championships from 1985-87 and were 29-7 during that span. They dominated Texas; winning six consecutive games from 1984-89 (the longest winning streak for A&M in the history of the rivalry).

“(Jackie) was a very positive, big-thinking guy,” Slocum said. “He elevated A&M football. He was coach and AD, so I learned a lot about the organizational part of the job.”

The old Southwest Conference, a rootin’ tootin’ league composed almost entirely of Texas schools (Arkansas was the lone out-of-state exception), had a cast of characters who could ably fill roles in The Magnificent Seven. There was Spike Dykes at Texas Tech, Ken Hatfield at Arkansas, Bobby Collins at SMU, Fred Akers at Texas, Grant Teaff at Baylor, Jack Pardee at Houston, Jim Wacker at TCU and Watson Brown at Rice.

“Everybody kind of knew everybody,” Slocum said. “They were competitors, but there were a whole lot of friendships.”

Dave Campbell’s hot publication, Texas Football, stirred the recruiting hype to mythic proportions while boosters ran amok. It was a glorious, scandalous time.

In December 1988, Sherrill resigned amid NCAA allegations, and Slocum was soon elevated to head coach of the Aggies. In his first game, A&M scored on the opening kickoff, a 92-yard touchdown run by Larry Horton. Also making his debut that afternoon was Ron Franklin, ESPN play-by-play commentator, who made the call: “Horton. At the 40, breaks it. He may score! At the 30! At the 10! Count it up … six points, Texas A&M!”

If this was a portent for things to come, the R.C. Slocum era was looking awfully bright. Starting with a bang, the Aggies defeated No. 7 LSU 28-16 that day and went on to an 8-4 record in 1989. Three of the four losses (Texas Tech, Arkansas, Pittsburgh) were of three points or fewer, and a 6-2 record was good enough for second in the conference.

It had been 17 years in the making. Slocum’s long-tailored dogma was a hodgepodge of principles he gleaned from Gibson, Bellard, Robinson and Sherrill. He subscribed to the GIGO Theory — “garbage in, garbage out; good in, good out.” And in a rough-and-tumble world where coaches were expected to act like brilliant madmen, Slocum was the resounding response to the question, “Can a nice guy be a winner?” The answer was yes. Absolutely yes.

Texas A&M increased rapidly under Slocum. The years 1990-95 were indeed his finest, as A&M went 9-3-1, 10-2, 12-1, 10-2, 10-0-1 and 9-3 in consecutive years. Also during that stretch, the Aggies won the Southwest Conference three years in a row, were undefeated in conference play for four consecutive seasons and solidified Kyle Field as a tougher venue to come out of alive than the Roman coliseum (notching a streak of 37 consecutive games without a loss). Eleven Aggies, including Aaron Glenn, Leeland McElroy and Marcus Buckley, made first team All-American, and the “Wrecking Crew,” the moniker for Slocum’s brawny, horn-mad defense, wreaked havoc on trembling quarterbacks from Waco to Lubbock.

For the fans, there was something about “R.C.” that was catchy and too good a fit for marketers not to capitalize on an old ad campaign for RC Cola called “Me and My RC,” and A&M pilfered the soft drink motto for the RC Slocum years. Slocum was beloved by fans, not simply because he was a good football coach, but because he was also a good man.

It would have seemed natural, at this point, for Slocum to have remained the head coach at Texas A&M forever, or at least until administration had to pry him out with a crowbar, exiting like many ailing coaches who prefer to chase glory and the ghosts of legacy, the nation grimacing at their demise. But the R.C. Slocum story did not end this way; it was more poignant than that.

While Slocum was trending upward in the early 1990s, the Southwest Conference was crumbling — “limping and wheezing” as Dallas Morning News writer Brad Townsend once put it. Texas A&M had eluded the NCAA detritus and was again the bell cow, but probation and scandal had so ravaged other schools (including SMU, Houston, TCU, and Texas Tech. Even mighty Texas did not escape the jaws of the NCAA) that the conference was in irreparable disarray.

At a coaches’ meeting in Florida, Slocum heard the first scuttlebutt that change might be in order. Was Texas looking around? Could the SWC shatter into bits? After making a few calls, Slocum learned that a meeting was scheduled to discuss the fate of the SWC. In the meantime, he phoned Roy Kramer, Commissioner of the SEC, to gauge the conference’s interest in acquiring A&M.

“I was all for the SEC move,” Slocum says reflectively.

According to Slocum, Kramer called back a couple of days later and relayed there was “significant interest” in A&M joining the SEC. Perhaps the move could be accomplished, Lord willin’ and the creek don’t rise.

Later, Texas Gov. Ann Richards and Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock called a meeting in Austin to discuss the fate of the conference. Slocum says that Richards, a Baylor graduate, and Bullock, a Texas Tech and Baylor graduate, suggested that if A&M were to move to the SEC, both Texas Tech and Baylor would piggyback as well. “The A&M and Texas Presidents were told that they were not going anywhere without Texas Tech and Baylor going with them,” Slocum told SDS.

In Slocum’s opinion, this bold utterance effectively ended the SWC and led to the founding of the Big 12 Conference, as four teams from the SWC (Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and Baylor), joined the teams of the Big 8 Conference to complete the Big 12 profile.

Slocum found this realignment to be much tougher sledding (Nebraska! Oklahoma!), and though he went into the Big 12 experience with high hopes, initially he could not imitate Texas A&M’s early-1990s success. In addition, A&M had been hit with probation in 1994 after the NCAA determined that several Aggies had procured jobs at an apartment complex for “little or no work” — a charge that Slocum and university president Dr. Bill Mobley argued was isolated and fully investigated.

After taking a step back with a 6-6 campaign in their Big 12 inaugural year in 1996, Slocum raised A&M to a division championship the next year and a conference championship two years later. Led by Vietnamese linebacker and one of the best defensive players in school history, Dat Nguyen, A&M rumbled to a 10-2 regular season in 1998, including wins over Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas Tech. As winners of the Big 12 South division, the Aggies were slated to play Kansas State in the Dr. Pepper Big 12 Championship at the TransWorld Dome in St. Louis.

Trailing 27-12, A&M mounted a furious comeback, forcing overtime by scoring in the final two minutes after a Wildcat fumble. The score remained tied after the first overtime, and in the second refrain, Martin (pronounced mar-TEEN) “Automatica” Gramatica booted a field goal on Kansas State’s possession to put the Wildcats up by three points. On Texas A&M’s possession in the second overtime, Aggie QB Branndon Stewart connected with Sirr Parker on a 32-yard slant to seal the win, 36-33.

Less than a year later, the ecstasy was over.

Tragedy and Healing

The No. 12 has always reserved a special place in the hearts of Aggies, but on Nov. 18, 1999, that number took on new meaning when a bonfire collapsed on the A&M campus, killing 12 people. The tradition, known simply as Bonfire, had grown over 90 years from a small gathering to the largest display of pyrotechnics in the world, as students heaped over a thousand tons of timber (five thousand logs) in wedding cake design before setting it aflame. Traditionally held before the Texas game, the first bonfire blazed in 1907, and before the incident in 1999 the school had lit 92 consecutive fires without tragedy. Out of the assortment of Aggie traditions (Yell Leaders, Yell Practice, The 12th man) Bonfire was the most anticipated and intricately organized, and had grown such that crews formed their own societies (leaders are called Redpots) who passed their construction acumen down orally to the next generation of builders.

In the dark and the cold of the early morning on Nov. 18, crews were negotiating the stack when the logs gave way, crushing the bodies of 12 and injuring 27 more. As America woke up and news of the tragedy spread, the former all-military school in southeast Texas had the world’s attention.

“There was press in here from all over the world,” Slocum remembers.

Awash with grief, Aggie Nation staggered throughout the next few days. Players showed up to assist rescue teams searching for survivors by helping to move logs and other debris. School administrators considered canceling the game, but when Slocum lobbied for it to be played (arguing that the students might draw strength from one another), officials relented.

“The human nature superseded the rivalry,” Slocum said. “The two alumni bases were the closest they’d ever been.”

Slocum also remembers the unmitigated grace of Texas coach Mack Brown who, setting rivalries aside, phoned every day to offer his aid during the week leading up to the game. “The human nature superseded the rivalry,” Slocum said. “The two alumni bases were the closest they’d ever been.”

The night before the game, a memorial service was held at A&M’s traditional Midnight Yell Practice at Kyle Field, where Slocum addressed the crowd. “The stadium was packed,” Slocum said. “Everyone brought candles. There was a special bonding that night before the game for the A&M family. It was a somber thing, a healing deal.”

By kickoff on Saturday, media coverage had reached a fever pitch, and compounding the macabre hype was that Texas was entering the game No. 7 in the nation. Although A&M’s practices throughout the week had been methodical and workmanlike, the Aggies charged onto the field with great emotion come game day. Kyle Field was brimming with over 86,000 fans — at the time the largest attended event in the history of the state of Texas.

Before the game, proper displays of respect were given to the deceased: 12 doves were released and four fighter jets screamed overhead in the Missing Man formation. A group of eight students seated shoulder to shoulder wore white T-shirts with a single letter painted on the chest, spelling out REMEMBER.

With A&M leading 20-16 with 23 seconds remaining, Aggie linebacker Jay Brooks sacked Texas quarterback Major Applewhite and Brian Gamble pounced on the ball to seal the win. Gamble then dropped to his knees near midfield, his face riddled with pain and praise. It was the culmination of eight hellish days that would be etched into the minds of Aggie Nation forever.

“The A&M family needed that win,” Slocum said later in a video interview. “The players … they willed it that it would turn out that way.”

In an article for the AP, offensive lineman Chris Valletta reflected, “We had the thought and memory of those 12 in our hearts and minds every single play.”

The bonfire disaster is Slocum’s darkest and most luminous hour as head coach, the light of love shining through turmoil. During the tragedy, Slocum was the undisputed leader and most powerful voice in the A&M athletics department. No one would have guessed that three years later, Slocum would be fired and replaced by Dennis Franchione.

By the end of 1999, Slocum was already the winningest head football coach in Texas A&M history, surpassing Homer H. Norton, who coached the Aggies from 1934-47 and won A&M’s only national championship. But after a 7-5 season in 2000 and an 8-4 season in 2001, a contingent of administrators began to wonder if Slocum was slipping, and Brutus and other conspirators quietly plotted to dispose of Caesar.

If Slocum’s coaching seat was lukewarm entering 2002, it was stifling by mid-November as the 5-4 Aggies headed into a matchup with No. 1 Oklahoma at Kyle Field. But A&M reversed course and defeated the Sooners 30-26 in one of the greatest upsets in school history. Unfortunately, the sigh of relief was short-lived. A loss to Missouri the next week readied the knives, and once the cardinal sin was committed — a 50-20 drubbing by Texas — the conspirators moved in for the kill.

On Dec. 2, R.C. Slocum was fired.

“We had a season where we lost several close games that could have gone either way and no one was more disappointed than me with our record. However, we have some really outstanding young players and I felt our future was bright,” Slocum said in a statement.

“A&M didn’t do this to us,” Slocum reflects now. “A few individuals did this to us, and you have to separate the two. A&M has been great to me and my family.”

Still dealing with shock and forced to clean out the office that took 14 years to break in, Slocum, who went 123-47-2 at College Station, received two head coaching inquiries (Baylor, Houston) by nine o’clock the next morning. More interest continued to file in, including the defensive coordinator position at Alabama under Mike Price and the same position with the Oakland Raiders and old pal Norv Turner.

Yet again, Slocum was forced into a think fast, act fast situation. He was only 59; surely there were more years left in coaching. But as he continued to ponder his next move, he surmised that his whole family, his whole life, rotated around the axis of Texas A&M. Though he was disappointed in certain individuals responsible for his ousting, Slocum held no animus against the school.

“A&M didn’t do this to us,” Slocum reflects now. “A few individuals did this to us, and you have to separate the two. A&M has been great to me and my family.”

Since 1972, save for one outlying season when he took a job at USC, Slocum had called College Station home. Not only was Slocum a coach, he was a Texas A&M fan; coursing through his veins was blood the shade of maroon. In the final analysis, Slocum did not want to pack his bags to go somewhere else and force his family to become fans of another program or franchise, simply for his sake. Instead, he decided to remain an Aggie for life.

Holding his head high and dusting himself off like a rodeo cowboy after getting bucked, Slocum accepted a job as a special assistant to Texas A&M President Robert Gates. Since that time, Slocum has assumed an ambassador-like role for A&M and for college football itself. He holds the title of President of the American Football Coaches Association and spends time giving plenty of speeches and attending charity golf tournaments. He is an avid hog hunter and owns a ranch 45 miles from College Station. He and his wife Nel live at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac in Bryan, where they host family gatherings soaked in maroon and white.

Viewing his school from a new position, Slocum has been pleased with the ascension of the A&M program under Kevin Sumlin and thinks the move to the SEC in 2012 has been beneficial. And, witnessing the rise and fall of the Johnny Manziel Empire, he laments that he could not have helped the superstar. “First of all, I would have loved to have coached him,” Slocum said of Manziel. “The times I’m around him, he is totally respectful. Very polite, very respectful. I’ve seen the problems, and I think it’s a tragedy. I’m sad when I read about him and I hope he gets his life together. My heart goes out to Johnny.”

Then Slocum leans in and for a moment is a coach again. His words roll off his tongue as if he believes they could jump from these pages and into the heart of Manziel. And though Manziel never played for him, in Slocum’s mind, he’s one of his players, too. Manziel is an Aggie, and that’s good enough. “One of the challenges in life is handling the downs,” Slocum says. “When things are really, really going poorly, don’t despair. Keep chipping away. Hang in there. Keep fighting. The opposite of that is when you’re riding high. Don’t get too carried away. Keep your feet on ground. Be concerned with who you are as a person. If I had a recommendation for Johnny, I’d tell him to get him a good Bible.”

Life in Pictures

When asked to list his Top 5 items in the “I Love Me” room, Slocum stumbles for an answer. “Hmmm … nobody’s ever asked me that question before,” he says.

Scanning the room, various substances made of metal, crystal, and bronze vie for the list, but first mention is a photograph taken in Greece with former U.S. President George H.W. Bush, a close family friend. “A shoeshine boy vacationing with a former president in Greece. That’s a long, long trip,” Slocum says.

Then he mentions another photograph: one of him and his sons. “This is very close to my heart,” he says.

Then he mentions another photograph. And another.

It becomes clear that the most important things in R.C. Slocum’s life are not awards or championships. They don’t include objects that will eventually turn to rust and gather dust. The most important things in R.C. Slocum’s life are the people he has met along his long journey. “When it’s all said and done, that’s all that matters,” Slocum says. “Wins and losses run together. Experiences and relationships with those people, that’s the single most important thing to me. There’s not a single day that goes by that I don’t talk to one of my players or coaches.”

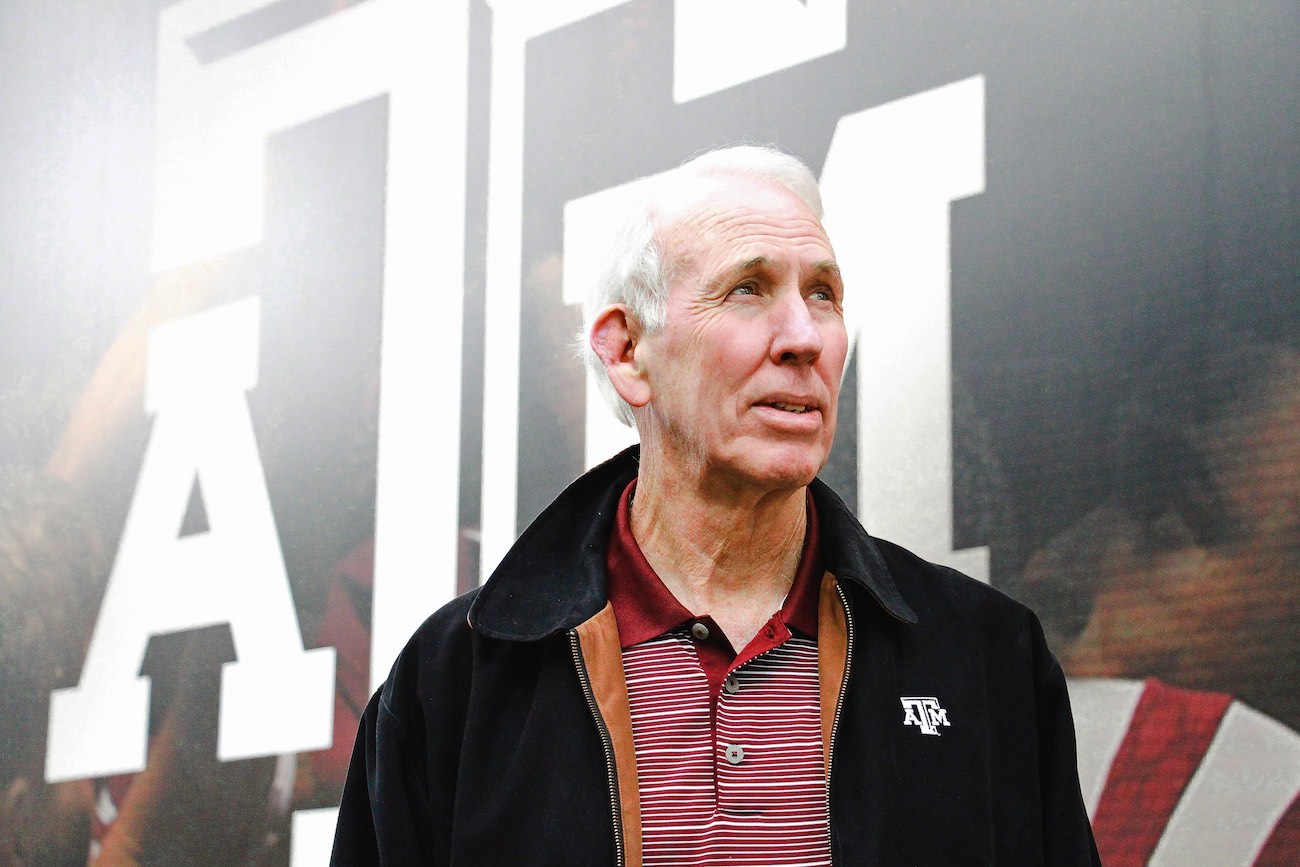

Later in the morning, Slocum rambles onto the A&M campus in his old F-250 truck. He parks the truck and charges across a concrete platform to a statue of John David Crow, Texas A&M’s first Heisman trophy winner, standing proudly in front of Kyle Field. Students walk past him wearing their headphones and slip-on sneakers, oblivious to who he is or the kind of impact R.C. Slocum has made on Texas A&M University. The sun is bright and harsh and the buildings around him form a complex with the majesty of Babylon. In the distance, a water tower reads WELCOME TO AGGIELAND.

Slocum pauses at the foot of the statue for a brief moment of personal reflection on his friend, who died in 2015. But seeing this statue of Crow could never matter more than knowing the man.

Then Slocum walks into the Bright Football Complex, a multimillion-dollar facility whose funds he helped acquire. He shuffles by the desk worker, throwing her a wave. He presses the elevator door button and climbs in. A story above, the door blasts open and he walks out. A glass door bears an inscription SLOCUM NUTRITION CENTER. He swings open the door and walks over to the cash register. Lisa, an African-American lady, flashes an amiable, gold-proud smile. When asked, Lisa doesn’t know that the man paying for his lunch has his name written across the door.

“I just started working here,” Lisa said.

Then Slocum begins talking to her. Within minutes, he’s already made a friend.

After negotiating the line, Slocum sits down at a table, the stone façade of Kyle Field looming in the background.

Finishing his food, he walks over and places his tray on the window. He speaks to the workers. Then he walks back by Lisa.

“I’ll remember him now,” Lisa promises as she says goodbye.

A Final Thought

It’s a long way from the abject poverty of a shoeshine boy to the winningest coach in Texas A&M history. And it’s a long way from Orange County, Texas to the kind of man R.C. Slocum has become.

There’s an old cowboy song called “The Texas Cowboy” that seems appropriate for the life of R.C. Slocum:

O, I am a Texas cowboy,

Far away from home;

If ever I get back to Texas

I never more will roam.

After all, there’s plenty of room at the Hotel California.

In addition to freelancing, Al Blanton is the owner of 78 Magazine, based out of Jasper, Alabama. Al is a lawyer and former college basketball coach who discovered a passion for writing. Follow Al on Twitter @78online

Al Blanton is the owner of Blanton Media Group, publishers of 78 Magazine and Hall & Arena.