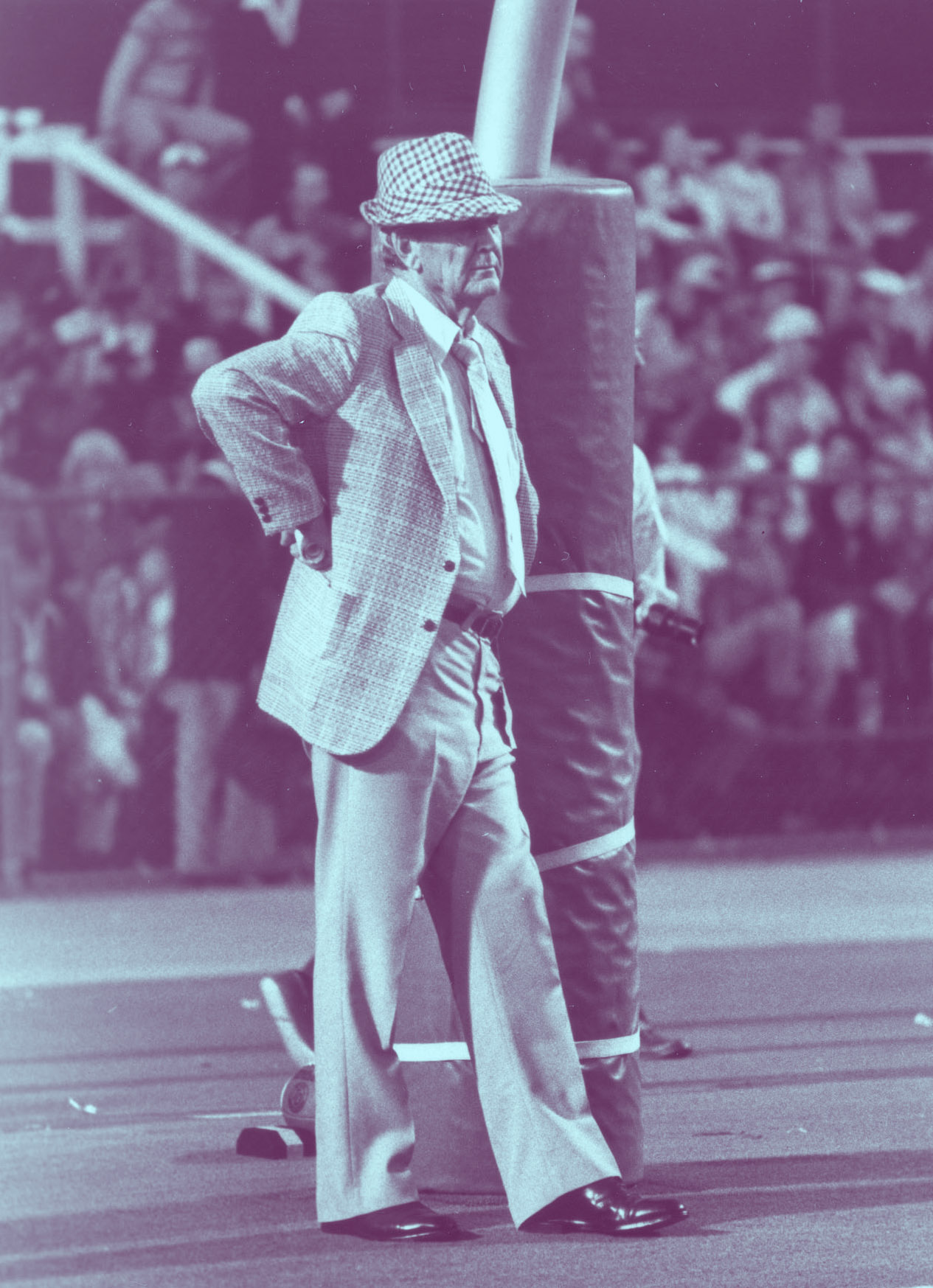

“He had a persona about him that was just different. He was a huge man. He had huge hands and had this rugged face, you know, deep cracks that ran through his real dark-complected skin. He just looked like leather, his face was leather. He talked with this gravelly voice. Real low where you had to lean in. You had to really pay attention when he talked ’cause he talked real low. So he had these mannerisms about him. And he was striking. When he walked into a room, the chemistry of the room changed. It got quieter. He was the focus of the room. And that would happen, certainly when he was with the team … but it was like that anywhere he went. His presence was felt.” — Johnny Musso

In Alabama, two things reign. One is religion, for if you closed your eyes while driving, you’d probably hit a church. The other is football, and often, folks in this part of the country get confused which is the more important. From Heron Bay to Ider, sermons about such idolatry ring loud and frequent from pulpits.

The cause for all of this obsessive behavior, I think, was a flawed yeoman from the Pentecostal community of Moro Bottom, Arkansas. Paul W. Bryant created a football frenzy in this state of which there is no parallel. Since 1958, the year Bryant arrived, Alabama has, as they say, been seeing red.

First, let us not pretend that Bryant is somehow Jesus Christ, or anything close to it. Even Bear himself, when commenting for a 1981 article for Sports Illustrated, said he hated “all that joking about him being some sort of Dixie Christ.” He never authored a bill or annexed territory or healed the lame or walked on water. Bryant is probably not the most influential figure in the history of Alabama; that denotation possibly goes to men like Jesse Owens or Wernher Von Braun or Martin Luther King Jr. But he is the most beloved. He is the most admired. His iconography is so immense and penetrating that no other dead man brings tears to the eyes of Alabamians as much as Paul W. Bryant. George Washington may have crossed the Delaware, but Bear Bryant beat Tennessee.

Bear Bryant retired with 323 victories, then the most in college football history. He won 232 games at Alabama and 60 at Kentucky. Both totals remain the program record.

As much as anything, the Arkansas fields from which Bryant came — tough, hardscrabble and toilsome — shaped and motivated him, and from this life, he spent a lifetime of escape. That time and those experiences also helped us to identify with him. Indeed, Alabama is and has always been a state wracked with poverty, and our champion conquered that red dirt and those mules to become the greatest coach who ever lived.

As a young boy, he wanted to play at Alabama. We can see him crouched near his radio, falling desperately in love with the sounds Alabama football, of a 1925 train chugging to Pasadena, where the boys in Crimson licked the giants from the Cascades. The country rube later confirmed his admiration, arriving on the tree-shaded campus in the fall of ’31.

We know he eschewed boasting of his playing greatness, preferring to describe himself as an “average” player, the “other end” on the 1934 championship team. We’ve heard the tale of the vicious leg break that rendered him — good gracious — able to still play against Tennessee, when guts and bravura and passion overcame the pain. But perhaps we haven’t heard the story of how Bryant himself learned not to quit while at Alabama. An excerpt from Bear: The Hard Life and Good Times of Alabama’s Coach Bryant sheds some light.

“Anyway, I was big-dogging around, talking about quitting and going to LSU, which was one of the few schools other than Alabama that had offered me a scholarship. I threw the name out just to be popping off. Coach Hank (Crisp) sent for me. He was down there where we had our equipment, and he had my trunk out. I had this big old country trunk. Don’t know why, because I didn’t have enough clothes to fill one-fourth of it. But he had the plowline out and said, “I hear you want to leave. Well, dammit, I want you to leave, and I’m here to help you and see that you do. Come on, let’s get that plowline out and tie this trunk up and get your ass out of here.” Well, you’ve never heard such crying and begging and carrying on. I finally talked him into letting me stay, and I never let out a peep about quitting again.”

We know him to be a man who served his country admirably in World War II, but we do not think of him principally as a soldier. Bryant’s military service was voluntary; he left a wife and daughter for a 3 1/2 year stint with the United States Navy. Allen Barra, in his comprehensive sketch of Bryant’s life entitled The Last Coach, recounted the near-death story of Bryant on the submarine, the Uruguay. “While sailing to North Africa, the Uruguay was rammed by another troop ship in the convoy. Bryant, in the middle of a poker game, grabbed his canteen and gun — an automatic carbine, actually, the standard issue for navy officers stationed on land bases — and ran topside. There he found hundreds of terrified soldiers, ‘praying, and I was leading ’em.’ There was an order to abandon ship; Bryant thought it was premature and disobeyed, urging others to do the same. The ones who listened to him lived. Two hundred other soldiers and sailors died in the water.”

Years later, Alabama football was essentially dead until its messiah arrived in a Cadillac from Texas A&M. The J.B. “Ears” Whitworth campaign swept over the Tide program like a 3-year drought, as four dusty wins emerged in three years. But Bryant was an expert in plowing, and the farmer’s first order of business was to eliminate weeds. According to Tom Stoddard, who wrote a deep account of Bryant’s first year at Alabama entitled Turnaround, approximately a hundred eager boys showed up in 1958 for the paring of Bryant’s initial roster. Only half survived.

For many who had experienced the ease of the Whitworth era, Bryant’s presence was like a lion showing up at a quilting club.

How he became Bear Bryant

“It was outside the Lyric Theater,” he said, according to the New York Times. “There was a poster out front with a picture of a bear, and a guy was offering a dollar a minute to anyone who would wrestle the bear. The guy who was supposed to wrestle the bear didn’t show up, so they egged me on. They let me and my friends into the picture show free, and I wrestled this scrawny bear to the floor. I went around later to get my money, but the guy with the bear had flown the coop. All I got out of the whole thing was a nickname.”

Bryant used every arrow of motivation in his quill. Vocabulary was a deterrent, as the term “quitter” was tantamount to mortal sin. Many once-elite athletes found themselves banished to the dungeon-like category of “fat turds,” a phrase Bryant used to describe loafers and overfed butterballs. And on occasion, he would use physical means, as in the case of Carl Valletto. Valletto was a returnee from the Whitworth era and an ex-Marine. A tough hombre, to be sure. During a drill, Bryant came down from the tower, snatched Valletto by the face mask and twisted him down to the ground.

Loyal-to-the-bone assistants such as Pat James, Carney Laslie, Gene Stallings and Jerry Claiborne were hard charging and complicit in Bryant’s rough-and-tumble brand of football. The reason for this was that they were as, if not more, afraid of him than the players. One illustration confirms this fact. Bryant once commanded his lieutenants to meet him at the office “first thing in the morning.” Unsure of the exact time and fearing Bryant’s wrath, assistant coach Dude Hennessey spent the night in the floor of his office.

Blood was not valued as a precious commodity by these assistants; much of it coagulated with the dirt of the practice field. Things got so rough that on one occasion, a player’s glass eye was knocked loose and the assistants scrambled to recover it from the powdery ground. Problem was, many of the players didn’t know it was a glass eye, and, seeing the cavity and believing it to be his real eye, were totally aghast.

Part of Bryant’s effectiveness stemmed from his ability to select these loyalists and let them do their job. There was genius in delegation. But, if there were ever an issue needing to be addressed, no greater statement was made than when the chain clinked on his tower and Bryant descended to the practice field. Many of his former players recalled the unique sound of the chain as if it were sound effects from an Alfred Hitchcock flick.

The geography of Bryant’s madness extended to the old gymnasium, where “weights” — essentially a blood-and-guts affair with stations and trash barrels strategically placed along the walls to inherit puke — were administered. That tradition continued through at least the early part of the 1960s. Charlie Stephens, who played receiver for Bryant during this time, recalls the arduousness of this winter program. “The coaches would blow the whistle, and for 45 minutes, you would not stop,” Stephens said. “There was a wrestling mat. They’d blow the whistle and see who could whip the other one. There were parallel bars, and you’d bend your elbow and walk down the length of the bar. They had a rope hanging, and you’d climb the rope. They had air dummies. You’d hit it and coil, and your legs would just give out. There was no water. We never had a timeout. Nobody ever stopped. I was there for 5 years and I never went to that gym when I didn’t feel my legs quiver. It was the most demanding part of our whole program.”

Because of Bryant’s early toughness (he earned his nickname in high school after wrestling a bear), the 1961 team that won the national championship set the standard for subsequent teams to follow. That squad permitted only 25 points the entire season and embodied hard nosed, jock strap football. With this team, essentially, Bryant taught us, “this is how it’s supposed to be done” and left the blueprints so successors would have no excuse. The Process? You want to talk about The Process? Bryant invented it. Even Nick Saban admitted, on the 50th reunion of the 1961 championship team, that these men set the bar — “He said it with feeling, too,” Lee Roy Jordan said. “He wasn’t just trying to snowball us.” The 2017 Alabama team won the national championship because it followed that standard.

Decades of dominance

Of course, one cannot speak of Bear Bryant’s career without mentioning the two incomparable decades of the 1960s and 70s. During this 20-year span, Bryant’s teams dominated the college football landscape, as six national championships were claimed (some of which have been questioned by critics and naysayers) and 12 of 13 SEC titles were added to the Tuscaloosa showroom. In the 1960s, Alabama was 90-16-5, and in the 1970s, 103-16-1. But those critical of Bryant’s championship success fail to acknowledge that he could have won more. No such system existed that funnels a team toward a championship as today, and besides the royal screwing in 1966, Alabama was arguably the best team in the country in 1962, 1975 and 1977. Had a Playoff or some other method similar to the BCS existed, had the Northeastern press have not had a stranglehold on the voting, there’s no telling how many Bryant might have won.

Yes, he had a reputation for taking average players and making them winners, but often understated is the brilliance behind the vetting. Many of his selectees in the late 1950s and ’60s, like Bryant, hailed from small towns. Lee Roy Jordan was from Excel. Billy Richardson was from Jasper. Charley Pell was from Albertville. Bill Oliver was from Epes. By the time they signed with Alabama, all had seen work: Jordan hand-pumped well water on a family farm. Richardson cut right-a-ways with a bush hook. Oliver drove a school bus. And Pell had lugged bricks at a construction site.

Bear Bryant led Kentucky to its first SEC title in 1950. He guided Texas A&M to a No. 1 ranking in 1957. In 1958, he returned to Alabama. Why? “It was like when you were out in the field, and you heard your mama calling you to dinner,” Bryant said, according to the New York Times. “Mama called.”

Often, during Bryant’s recruiting process, the players wondered if they possessed the talent to compete on the college level. Jordan chose Alabama over Auburn because “I might have thought I couldn’t compete with athletes at Auburn because they were so big.”

Though Richardson was diminutive at only 5-foot-9 and 175 pounds, Bryant looked more at the heart than the frame that housed it. The first recruiting call Richardson received from Bryant was in the fall of 1957 while he was still the head coach at Texas A&M: “When Coach Bryant called me, I’ll never forget. I had not talked to him before,” Richardson said. “My mother called me to the phone. She said, ‘Coach Bryant’s on the phone. You wanna speak to him?’ I picked up the phone and he said, ‘This is Coach Paul Bryant calling you from College Station, Texas. I’m out here with some of my old Alabama buddies, and they told me you were a pretty good football player. I wanted to see what you think about that.’ I told him, ‘Coach you’ve never seen me. I know you‘re with your A&M team, and John David Crow won the Heisman. He’s a big bruising running back. I weight about 175 pounds.’ ‘I don’t know where in the hell you don’t think I play little guys,’ Coach Bryant responded. ‘A few years ago, my best player, Roddy Osborne, weighed 155 pounds soaking wet.’”

Individually, they might not have been the most talented, but once he cobbled these hungry individuals together, he was a master at making them believe. “You didn’t want to disappoint him,” Lee Roy Jordan said. “He would build you up and present to you how good you could be. He had a way of convincing all of us to be a loyal teammate and what we needed to be to win a championship.”

We know that Bryant could be tender, as exhibited in his relationship with Pat Trammell, whom he loved with son-like affection. While others might have bowed to Bryant’s ire, Trammell challenged him, and in turn Bryant possessed enough savvy to give his leader some rope. During the fourth quarter of the Auburn game in 1961, Trammell quick-kicked on third down with Alabama leading 34-0. It was a play that was unaccredited by Bryant. As Trammell was walking off the field, Bryant approached him.

“What’s going on, Pat?”

“Those — aren’t blocking anybody, so I thought we might as well see if they can play defense,” Trammell huffed.

Bryant turned and walked away.

Later, Bryant sobbed over Trammell, who, at age 28, left the earth too soon. Through the life of Trammell, we saw Bryant’s capacity for emotion, the great converse of his tough, man’s man demeanor. As Mickey Herskowitz noted, “He was like the old-time cowboys, who could brave the hardships of the range and then weep at a painting on a bordello wall.”

He was always available to make others who looked differently and acted differently feel like they were a part of something. When Joe Namath first appeared on campus, swashbuckling onto the practice field in his swank western Pennsylvania, pool-hall attire, Bryant graciously invited the young gunslinger up to the tower. “Come on up here, Joe!” was Bryant’s invitation to the odd-looking Yankee. Understanding that Joe needed a special touch of grace so the boys would accept him was Bryant’s wisdom in this moment.

Tales from the huddle

Bryant’s virtuosity was found in unpredictability and willingness to adapt. Duteous in his planning, he wasn’t so bullheaded as to avoid change or improv. When his players expected an irate halftime salvo, he presented calmness and hand-clapping encouragement, such as during the Georgia Tech game in 1960 when ‘Bama was trailing 15-0 at the half. “He came in the dressing room whistling and laughing and clapping and patting us all on the backs, telling us what a good job we were doing and that we had them right where we wanted them,” said Bill Battle, who played end from 1960-62. “He said we were going to win the game, and we did, 16-15, on the last play. That was a very different approach for Coach Bryant, and it probably won the game for us.” Jimmy Sharpe, who played for Bryant and later became the head coach at Virginia Tech, recalls Bryant handing out Cokes and towels during this immortal halftime speech.

Bear Bryant went 19-6 vs. Auburn. His final victory in the Iron Bowl (28-17 in 1981) was his 315th overall, moving him ahead of Amos Alonzo Stagg on the all-time victories list.

Lee Roy Jordan remembers well the game against Oklahoma on January 1, 1963, not simply because he logged 30 tackles that afternoon, but also because Bryant used President Kennedy as a source of motivation in his pregame pep talk. Kennedy was in attendance because Bud Wilkinson, head coach at Oklahoma, had been selected to serve on the President’s Council on Physical Fitness. As Jordan remembers, Bryant came into the ‘Bama locker room before the game and said, “Well, the President didn’t come in here to see you guys, I can tell you that. He was over there hobnobbing with the Oklahoma guys. Let’s go out there and kick their butts!”

Just when you thought the program was dead, five loss seasons — heaven forbid — appearing on the ledger, Bryant performed a resurrection. When his offense and his team went stale in the late 1960s, he covertly switched to the Wishbone. Three weeks before the 1971 season opener, Bryant, to everyone’s surprise, installed the Darrell Royal-inspired triple option and ran over USC like a Mack truck. The driver was an Italian named Musso.

Alabama went to great lengths to disguise their plan. Bryant put up a curtain around the practice field fence and told his players to keep quiet. One day when skywriters appeared on campus to give prognostications for the 1971 season, Alabama masqueraded the change by reverting back to I-formation drills. “We wasted a whole day of practice there,” Musso said.

The secret wasn’t revealed until Alabama’s first possession in L.A. Coliseum. Even in pregame warm-ups, Alabama showed the I. “We caught USC totally, one hundred percent off guard,” Musso said. “They had a better team. They were picked No. 1 in the country that year. They had great athletes. I think if they would have been prepared for the Wishbone, we probably wouldn’t have beaten them. I’m sure of that, actually.”

The bloodlust continued through the decade of the 1970s as Alabama was once again drunk on the elixir of winning. Alabama’s dominance was punctuated with back-to-back championships in ’78 and ’79, and a famous Goal Line Stand that illustrated the heart of Alabama football.

In his later years, Bryant demonstrated flashes of his youthful exuberance. Jeremiah Castille, Tide defensive back from 1979-82, once recalled a story when a storm had forced Alabama to practice at Tuscaloosa High School. During the practice, Bryant, unimpressed with the direction of the exercises, sent his coaches to the stands. “He coached the entire scrimmage by himself. Every position. Did all the substitutions, going up and down the field for six hours,” Castille said. “At the age of 68, Coach Bryant still had energy and enthusiasm. That influenced me to get up every day and live life to the fullest.”

But perhaps his most important lesson was his message about class, a message that is being lost by modern society. If Bryant were here, he would lament that our country had somewhat detached from these moral and ethical moorings. Branding himself as a simple plowboy, Bryant was a gentleman behind his aw-shucks façade.

Alabama’s current problem is deciding which coach — Saban or Bear — is the GOAT, the Greatest of All Time. With the checkered hat, the Golden Flake and Coke spots, the clever quips, and the hell-for-leather preseason camps, there is little doubt as to who is the more iconic. Publicly, the difference between the two is that while Saban largely refuses to pull back the curtain of his personal life, Bryant invited us in. In many ways, Bryant allowed us to see his flaws. He was a man we could touch and feel and smell. I was 5 years old when he died, but I felt like I knew him.

I still cry for Bear Bryant, and I don’t know why.

It was just him

After the 1961 National Championship, members of Alabama’s team were invited to New York to be presented the MacArthur Bowl by Navy hero and fellow Arkansan Gen. Douglas MacArthur. One might wonder what keen words might have passed between Bryant and the old soldier that splendid evening. Young Boozer, one of Bryant’s teammates at Alabama and a longtime friend, recalled what MacArthur said as he presented the trophy. “It is a privilege and an honor to meet you because you are one of the few remaining men among us who knows what discipline is and how to teach it. If we don’t get back to discipline, I don’t know what this country is going to come to.”

Bryant biographer Mickey Herskowitz, the longtime journalist for the Houston Chronicle, memorialized Bryant thusly: “No, I didn’t think that he had put down the yard markers in the Garden of Eden, or discovered Joe Namath in the bulrushes of the Nile and driven the Crimson Tide to glory with a series of Sermons on the Mount. But I thought there was something in him that went beyond the scoreboard, and I noticed that his players learned from him, just by being around him. I saw him as a folk hero, long before that was the widely held view.”

Bear Bryant won 6 national titles at Alabama. Nick Saban recently matched Bryant’s record.

After Bryant passed in January 1983, President Ronald Reagan issued a tribute to the coach whose influence bled over into the American consciousness. “In many ways, American sports embody the best in our national character — dedication, teamwork, honor, and friendship,” Reagan said. “Paul Bear Bryant embodied football. The winner of more games than any other coach in history, Bear Bryant was a true American hero. A hard but beloved taskmaster, he pushed ordinary people to perform extraordinary feats. Patriotic to the core, devoted to his players and inspired by a winning spirit that never quit, Bear Bryant gave his country the gift of a legend.”

True legends don’t plan to become what they eventually become. Such is the case with Bear Bryant. Often, when people try to explain the greatness of Bryant, they are left scratching their heads. Was it his work ethic? His magnetism? His drive? His passion? His knowledge? His ability to motivate? His wisdom? His confidence? The answer to all these questions is “yes.”

But the best answer is that it was just him. Bear Bryant was great because he was Bear Bryant.

Had some other field have called, Bryant might not have been so great. Retrospectively, it doesn’t seem natural to imagine him selling Pontiacs at the local dealership, or operating on a broken bone, or running a Sno-Biz hut for a living. He was a football coach to his core. It’s what the Good Lord called him to, and thankfully for us, Bryant answered that call with vigor.

The enthralling life of Bear Bryant has been dissected more than any other biography in Alabama history. He is the most written about figure, most psychoanalyzed, most celebrated. Outside of friends and family, rare is it that one’s life is remembered a month after death, but in the case of Bryant, 35 years after his passing, his legacy has barely begun to fade.

Right now, he is the subject of discussion in greasy spoons and bait shops. Somewhere, an old man is gazing at his framed picture on the wall, or telling his grandchildren of the time he once got to shake his hand. Today, children will tour his museum and bright smiles will light up their faces as their daddies tell of his legend. A former player will field a call from a reporter seeking intrigue into his life. And someone will defend his honor against the blasphemous charges that he was not the greatest of all-time.

Voyeurs to his life and commentators like me have the luxury of referring to him as “Bear.” But no former player or staff member addresses him as anything but Coach Bryant. To them, he is not Bear, or Paul, or Bryant, or anything else. Essayist Wright Thompson, describing this reverence, even down to the pronunciation of Bryant’s name, once wrote: “like it was a Southern debutante’s double name. Always, Coach Bryant, just like Mary Wilkes or Sarah Catherine: Coachbryant.”

Bear Bryant won 159 SEC games, which remains the record.

I don’t know how much folks from other places outside the South care about Bear Bryant, don’t know the kind of impact he might have had on them, if any at all. But here in Alabama, Bear Bryant taught us about hope. He taught us to believe in ourselves. He taught us never to quit. He taught us to love our mommas and daddies. He taught us to work hard at what we do, to put our whole heart in it. And what it takes to be a winner.

California has the splendor of the Pacific sun. South Dakota has Mt. Rushmore and the Black Hills. Arizona has the Grand Canyon. New York has the Manhattan skyline.

Alabama has Bear Bryant.

And that’s all right with me.

All photos courtesy of the Bryant Museum / Alabama Athletics.

Al Blanton is the owner of Blanton Media Group, publishers of 78 Magazine and Hall & Arena.