Film Study: How Auburn can attack Alabama’s defense (Really)

By Matt Hinton

Published:

Film Study: How Auburn can attack Alabama’s defense (Really)

Hard as it might be to recall now, it was just a couple of weeks ago that the notion of Auburn springing an eleventh-hour upset on Alabama was beginning to gain some traction. Remember that? It’s true: The Tigers were hot, certifiably, winners of five straight following a 2-2 start, and putting up numbers offensively reminiscent of the 2013 team that bounced a similarly invincible Bama outfit from the SEC and BCS title games. Unranked in September, by the first weekend in November they climbed to No. 9 in the Playoff Committee’s weekly rankings, and as high as No. 8 in the AP poll.

Now? On the heels of a dismal, 13-7 flop at Georgia, the Tigers will arrive in Tuscaloosa on Saturday as 20-point underdogs, with nothing larger at stake outside of the context of the rivalry. They don’t even have the satisfaction of playing spoilers — Bama can’t be caught in the SEC West standings, and its lead is so large in the national polls that it can almost certainly survive a loss with playoff position intact. Speaking strictly hypothetically, of course, because no one expects Bama to lose.

Offensively, the Tigers are banged up. The starting quarterback, Sean White, missed last week’s gimme win over Alabama A&M with a bum shoulder after neglecting to inform coaches of the extent of the injury in the loss to Georgia; his status for the Iron Bowl is TBD. Jumbo tailback Kamryn Pettway, the engine of the October surge, is expected to play after sitting out the past two but will likely be at less than full speed; ditto for H-back Chandler Cox and all-purpose back Stanton Truitt. This, against an Alabama defense that’s yet to allow a touchdown in the month of November.

Then again, since when is Rivalry Week in college football supposed to make sense? In the spirit of chaos and ancient, entrenched intrastate hate, this week’s breakdown is all about giving the Tigers a fighting chance: Can the offense rekindle its midseason spark? Where is Bama vulnerable defensively, or (let’s be real here) potentially vulnerable? How might that play into Auburn’s strengths? Is there anything on the record that undermines the inevitability of another Crimson Tide rout?

Most important, if the Tigers manage to find a soft spot, what does it mean for the rest of the Tide’s march toward back-to-back national crowns? Because if we know anything about this time of year in college football, it’s that surprises are inevitable and longstanding assumptions can change in a blink.

Back to the Grind

As always in the Iron Bowl, any remotely plausible blueprint for an Auburn upset begins and ends with establishing the run. And, as always, at first glance the Tigers’ chances of actually pulling that off appear grim. So far Bama’s front seven has been a black hole on par with Saban’s best: Typically, the Tide lead the nation by huge margins in rushing defense, yards per carry allowed, Defensive Rushing S&P+, and Adjusted Line Yards, numbers befitting a group bound for the NFL en masse.

No team has yielded fewer touchdowns on the ground or fewer runs of 10 yards or more. Only two opposing offenses this year (Ole Miss and Texas A&M) have cracked 100 yards or 3.0 yards per carry as a team, and just barely in both cases; LSU, the best rushing attack Bama has faced, didn’t even come close.

But Auburn isn’t exactly chopped liver up front itself, and with Pettway in the lineup the ground game has been borderline unstoppable — in Pettway’s seven starts the Tigers have averaged 285.6 yards per game on 5.3 per carry, including bona fide romps against Arkansas (543 yards on 9.5 per carry) and Ole Miss (307 on 5.9) in consecutive weeks. (It was after the Ole Miss game that Pettway said, “nobody really wants to tackle me,” and he wasn’t wrong.)

For his part, Pettway has accounted for a little more than half of that total, most of it coming in relentless, 4- and 5-yard chunks on inside zone plays that keep the chains moving. At 240 pounds, he’s ideally suited to absorbing (and dishing out) the punishment that comes with carrying the ball 25 times per game, a number he hit in four consecutive games before pulling up lame on a breakaway run against Vanderbilt.

Pettway is a straight-ahead thumper, not shifty or elusive, but for a converted fullback he does have some respectable wheels in the open field: Including that ill-fated example against Vandy, he has nine runs of 20 yards or more, and three that have covered at least 50 yards. His capacity to shoulder a full workload coming off the injury is essential to controlling the clock, opening up the rest of the playbook, and keeping the game within reach.

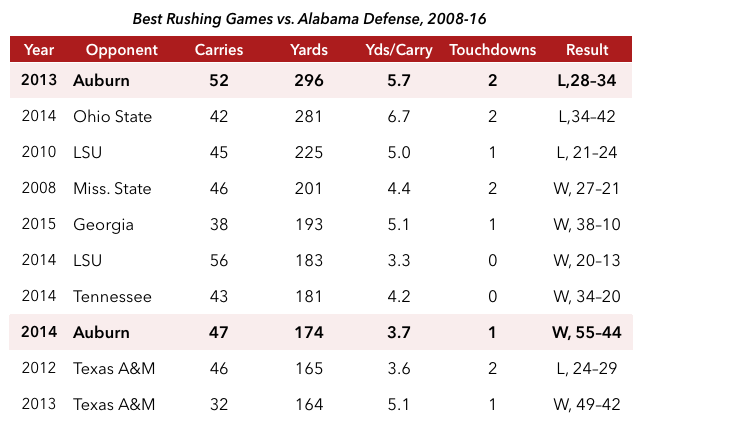

If Pettway has enough gas in the tank to serve as the focal point for four quarters, then there’s plenty of evidence that Gus Malzahn knows how to get the most out of his rushing attack in this game: Two of his first three seasons as Auburn’s head coach — and the 2013 Kick Six game, in particular, in which then-emerging workhorse Tre Mason abruptly surged into Heisman contention — produced two of the best rushing performances against Alabama since the Saban Death Star became fully operational circa 2008.

Pettway can’t put up those kinds of numbers by himself, but his presence as a reliable threat between the tackles can open up the dizzying array of speed sweeps, counters, quarterback runs, and other bells and whistles that Malzahn loves as a complement to the bread-and-butter.

Auburn has plenty of potential lightning to pair with Pettway’s thunder, most notably sophomore Kerryon Johnson, who has a decent chance of joining Pettway in the 1,000-yard club by year’s end despite battling injuries of his own; this weekend will be the first time both backs will be (relatively) healthy enough to share the same backfield in two months. And while no one is about to confuse Sean White with Nick Marshall on the zone read — a fact of which White has been reminded constantly — he’s not a statue, either, as he’s had a few occasions to demonstrate.

The Tigers don’t necessarily need White to go 40 yards (or 45, as Marshall did for the opening salvo in the 2013 game), but he does need to pose enough of a threat to either a) force Alabama to respect him in the zone-read game, or b) make them pay for it in small doses if they don’t. In a game in which every first down is likely to be hard-earned, at least a couple of them will have to come via the quarterback’s legs, bum shoulder or not.

Passing The Test

Of course, if Auburn was choosing its starting quarterback based on his potential in the running game White never would have seen the light of day over Jeremy Johnson or John Franklin III in the first place. White solidified his status at the top of the depth chart because he’s a much better decision-maker in the passing game, where Bama has been slightly — emphasis on slightly — more vulnerable.

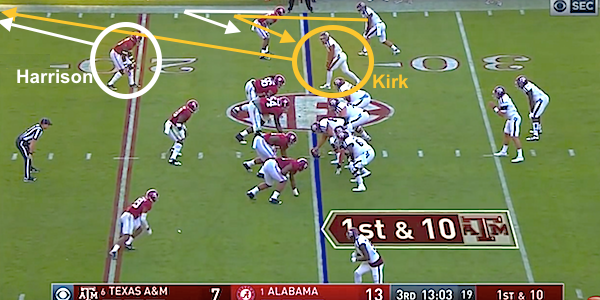

Excluding the odd busted coverage, one way that opposing passing attacks have stung Bama is by generating favorable matchups, which are few and far between but can be had. Take this play, for example, on which Texas A&M was able to get one of the SEC’s best receivers, Christian Kirk, isolated one-on-one against a safety, Ronnie Harrison, out of the slot.

On the previous play, the outside receiver to the top of the formation, Jeremy Tabuyo, had beaten cornerback Marlon Humphrey on a post route for a 33-yard gain, A&M’s longest of the game rushing or passing; this time, Tabuyo will occupy Humphrey in the flat by running a quick hitch route, leaving Harrison all alone against Kirk. Harrison is an outstanding athlete and a very good safety, but opposite a receiver as dynamic as Kirk he’s a step too slow to make a real play on a perfectly placed ball from Trevor Knight:

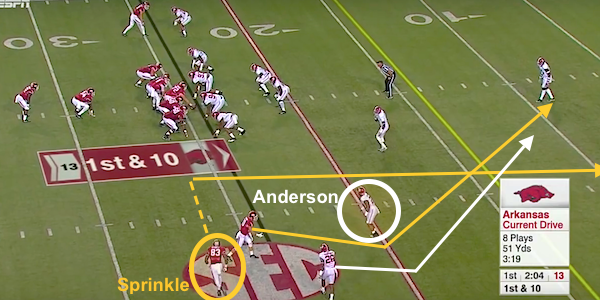

Another example, and probably a more relevant one for Auburn, is this play by Arkansas, a run-first team on a run-first down (1st-and-10 in the first quarter) that broke the huddle in this case with run-first personnel — facing both a fullback and a tight end, Alabama countered with a fourth linebacker in place of the standard nickel corner it employs against spread sets.

The wrinkle here is that by splitting the tight end, Jeremy Sprinkle, as effectively a third wide receiver, then motioning him into the slot, Arkansas was able to match up Sprinkle in space against outside linebacker Ryan Anderson (No. 22), a ferocious edge rusher who is decidedly less comfortable attempting to hang with one of the conference’s best pass-catching tight ends in man-to-man coverage.

Auburn hasn’t featured a traditional tight end at all this season (although it has in the past under Malzahn) and rarely throws to fullback/H-back Chandler Cox, a lead blocker with only four receptions on the year. Instead, the Tigers try to catch defenses flat-footed with an onslaught of motion into and out of the backfield by a clique of undersized, dual-threat types like Johnson, Stanton Truitt, Eli Stove, and Kam Martin, all of whom are threats to take a handoff or take off downfield on a pass route on any given play. When the running game is on schedule, the opportunity for a big play through the air increases dramatically.

An example I’ve used before to illustrate the ideal synergy between Auburn’s running game and passing game is this play, in the blowout win over Arkansas, which came near the end of a first half in which Auburn had thoroughly dominated the Razorbacks from the opening snap — a jet sweep that Stove took to the house from 78 yards out.

As 78-yard touchdown runs go, that’s about as easy as it gets, largely due to the linebackers’ preoccupation with stopping Pettway between the tackles. After that game, though, Malzahn admitted that the first play was conceived less for its own sake than as a setup for another play later on off the same look, which also went for a touchdown.

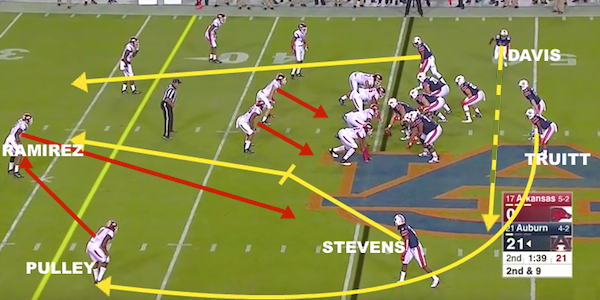

At this point, Truitt, a converted wide receiver, had already run for one touchdown to extend the Tigers’ early lead to 21-0, and White’s only pass attempt beyond 5 yards downfield was a badly underthrown ball in the first quarter that should have been intercepted. Understandably, having been burned once by the jet sweep and yet to be challenged deep, Arkansas safety Santos Ramirez (No. 9) reacts aggressively to the pre-snap motion to his side of the field, flying into the box as soon as Davis starts across the formation.

At the same time, though, that left cornerback Ryan Pulley (11) all alone vs. Tony Stevens, who — just as he did on Stove’s ice-breaking touchdown run — initially works inside as a would-be blocker before taking off down the middle of the field; although he has deep-middle help from the opposite safety, Josh Liddell, Pulley still elects to follow Stevens inside, leaving Truitt all by himself on a well-timed, well-executed wheel route out of the backfield.

Against Alabama, the Tigers will have to be similarly creative off of their base offense, because Auburn’s wide receivers vs. the Crimson Tide’s corners is a matchup that decidedly favors the latter. In the three games I reviewed of Alabama’s defense, Arkansas, Texas A&M, and especially Ole Miss all had some success attacking CB Marlon Humphrey; the Rebels alone burned Humphrey for gains of 32 yards, 37 yards, and 44 yards, and he was also on the wrong end of a 16-yard touchdown pass by the Razorbacks.

In each of those cases, though, Humphrey was matched up against a bigger receiver (Damore’ea Stringfellow and A.J. Brown in Oxford, Keon Hatcher in Fayetteville) who was able to come down with a heavily contested catch.

Auburn’s top wideouts, Tony Stevens and Kyle Davis, pass the eye test at 6-foot-4 and 6-2, respectively, but haven’t made a habit of outmuscling SEC corners for jump balls. As the Georgia debacle showed, the Tigers’ passing game is very much an extension of what it’s able to generate off the run.

To Saturday and Beyond

I’ve said before that there’s no blueprint for beating Alabama — the Crimson Tide’s sporadic losses under Saban don’t follow any pattern except that almost all have been out-of-the-blue upsets that no one saw coming.

If any rival coach can be said to have a bead on how to effectively attack Saban’s defense, though, it’s Malzahn — not only did he have a hand in a pair of unforgettable wins over Saban, in 2010 and 2013, but he also has experience in down-to-the-wire losses in 2009, when Auburn came within a few seconds of knocking Saban’s first BCS championship team out of the title game, and last year, when the eventual champs were unable to slam the door until well into the fourth quarter of a defensive slugfest. Both of those Auburn teams were heavy underdogs against a Bama outfit en route to the national title, yet managed to give the Tide all they could handle.

This year, the Tigers are much better suited for another slugfest than the guns-blazing shootout the teams put on two years ago, or even the 2013 edition, which required four offensive touchdowns just to be in position to win with the insane final play. Realistically, 20 points from offense this weekend is optimistic even if White is able to play at his usual level and even if you believe Auburn can get Pettway going on a couple extended drives.

The strength of Auburn’s team (like Alabama’s) is its defensive front, and the Tigers will be perfectly happy to settle for a replay of Alabama’s scoreless-through-three-quarters win at LSU if it means they’re still within striking range in the fourth.

To have any chance at all, though, at some point Auburn will have to leverage whatever success it’s able to muster on the ground into a game-breaking play, or several of them if Bama is unwilling to play along with a defensive struggle. The only two attacks that have managed that this year, Ole Miss and Arkansas, both undermined their success with a barrage of turnovers. If Auburn can’t break through, then it will remain any open question as the Tide roll into the playoff whether anyone can.

Matt Hinton, author of 'Monday Down South' and our resident QB guru, has previously written for Dr. Saturday, CBS and Grantland.