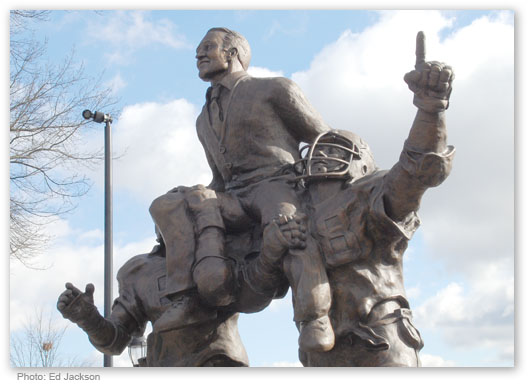

“There is perhaps no one person more singularly identified with the University of Georgia than Vince Dooley,” reads the opening line of the great coach’s biography in the Georgia Encyclopedia (georgiaencyclopedia.org).

He is the coach that, nearly 30 years after he coached his last game, still casts a shadow on the Bulldogs football program. He holds the school record for coaching victories, 201, and guided Georgia to its last national championship in 1980.

In 25 years at the helm, Dooley experienced just one losing season; and that was because he elected to go for a 2-point conversion in a 7-6 loss to Clemson in 1977 rather than settle for a tie by kicking an extra point with 20 seconds left.

Furthermore, behind Herschel Walker, Dooley wrestled control of the SEC from Bear Bryant. From 1971-79, Alabama won eight SEC championships, the lone exception being Georgia’s Sugar Bowl season of 1976.

But the Bulldogs followed Alabama’s streak with three consecutive conference championships of their own as Dooley joined Bryant, still at the Crimson Tide’s helm, and Bob Neyland as the only SEC coaches to that point who could make such a claim.

Still, as impressive as Dooley’s career was, he has a legitimate challenger for the title of “All-Time Georgia Head Coach.”

Say the name Wally Butts and two thoughts come to mind for most fans: a passing genius and the question if he conspired to fix a game with Bear Bryant in 1962 that resulted in a 35-0 Alabama victory.

The latter charge has been largely rebuffed. Butts won a libel case against The Saturday Evening Post, the magazine that made the charge against Butts. The case would famously go to the Supreme Court, establish precedence on the difference between public figures (such as prominent football coaches) and public officials (such as politicians) in libel cases, make Butts a wealthy man and the Post a defunct publication.

The other claim is true, and it could be argued Butts is something of an innovator of the modern passing game in football.

When Butts became the head football coach at Georgia, most teams ran the single-wing offense, where the halfback is the primary focus of the offense instead of the “T” formation, where the ball is snapped to the quarterback. The Bulldogs were no exception, but Butts made it into something other than a smashmouth offense.

“Philosophically, he was like Steve Spurrier,” said Loran Smith, a Georgia Bulldogs historian who authored Butts’ biography. “Only the Southwest Conference threw the ball at his time. TCU in that era, they threw the ball.”

Of course. Texas Christian is the alma mater of Sammy Baugh and Davey O’Brien, though they had graduated by the time Georgia took on the Horned Frogs in the Orange Bowl following the 1941 season.

In their place, TCU had Kyle Gillespie, whom his coach, Dutch Meyer, believed was even better than the aforementioned legendary quarterbacks.

But though both teams threw 24 passes, Georgia threw for 281 yards compared to TCU’s 137. Junior Frank Sinkwich, playing with a broken jaw, threw three touchdown passes in the first half to give Georgia a 33-7 lead at the intermission. Sinkwich would later add a 43-yard run and account for 355 total yards in a 40-26 Bulldogs triumph.

It was the Bulldogs’ first bowl game, and first ranking in the AP Poll.

The following year, with the arrival of Charley Trippi, the Bulldogs set a school record with 11 victories. Throwing 253 total passes, Georgia spent the entire season in the top five. Sinkwich won the Heisman with 1,722 total yards, scored 17 touchdowns, threw for 10 more, and even added 102 points as the Bulldogs placekicker, while quarterback Trippi posted 1,389 total yards of his own.

The total of 253 passes may not seem like much today, but consider it meant that Georgia was throwing a pass on one of every three plays from scrimmage. For comparison’s sake, when O’Brien won the 1938 Heisman Trophy and the Horned Frogs were revolutionizing the game by emphasizing the quarterback, they averaged 18 passes and 44 rushes a game, averaging a little more than one out of every four plays from scrimmage at 28 percent.

A late-season loss to Auburn ruined the Bulldogs’ chances for an undefeated season, but Georgia still took the Rose Bowl, 9-0, by throwing 30 passes compared to UCLA’s 15. While finishing one spot behind No. 1 Ohio State in the AP Poll, Georgia took national championship honors from six other organizations for the ’42 season.

Four years later, behind sophomore quarterback Johnny Rauch, the Bulldogs posted their first perfect season, finishing only behind the legendary 1946 Notre Dame and Army teams in the polls and taking national championship honors from Williamson. Rauch would finish his career with an unprecedented 4,212 passing yards as a four-year starter, himself following in Sinkwich’s footsteps by playing with a broken jaw.

The most famous of all Bulldogs quarterbacks, however, was Fran Tarkenton, who guided Butts’ last great team in 1959.

By this time, Butts was calling for more running plays. Though Tarkenton led the SEC in pass attempts in both ’59 and his senior 1960 season, he never threw 200 passes in a season.

However, what he did do was throw to his running backs. Two of Tarkenton’s three top receivers in ’59 were running backs, and leading receiver Bobby Towns split time in the backfield and flanker positions. The following season, three of Tarkenton’s top four receivers were backs, with future Buffalo Bill Fred Brown leading the team with 31 catches and three touchdown receptions.

This is a most telling statistic, as both Tarkenton and Rauch were purveyors of the short passing game in pro football.

Tarkenton is ready to handle the pro game upon arrival into the NFL. He starts his first game for the expansion Minnesota Vikings and throws four touchdown passes against the Chicago Bears in a 37-13 upset.

But what is telling about this game is that of the 19 passes the Vikings complete, 10 are to running backs. The story of Tarkenton becoming the first NFL quarterback to fully utilize the short pass is well-known, but so is the story of the Oakland Raiders adopting this philosophy in the American Football League.

And the Raiders of that era were coached by Rauch.

Sure, everyone remembers Oakland Raiders quarterback Daryle Lamonica’s nickname, “The Mad Bomber,” throwing long with such proclivity that even the great Billy Cannon, a tight end on the 1967 Raiders, could average nearly 20 yards a reception while hauling in 10 touchdowns to lead Oakland to Super Bowl II.

But the leading receiver of that team was actually running back Hewritt Dixon, who caught 59 passes out of the backfield.

“Most AFL teams ran man-to-man,” said Rauch’s son, John Jr. “That’s why Dad had to run to the backs. They were able to beat linebackers one-on-one.”

And the backfield coach of the 1967 Raiders was none other than Bill Walsh, credited as the father of the modern “West Coast” passing offense that utilizes the short pass.

So let’s recap. Walsh is considered the father of the modern passing game and learns under Rauch, who learns under Butts.

Butts, incidentally, was very close with Notre Dame coach Frank Leahy, who played under Knute Rockne, and everyone who has ever seen the film “Knute Rockne All-American” knows the story of how the forward pass in effect debuted in Notre Dame’s famous 1912 upset of Army after Rockne theorized it would be the best way for the Fighting Irish to overcome the Cadets’ size advantage.

So, Butts is actually a very essential link in the evolution of the forward pass, from its inception to where it is now.

One might even make the argument Butts was a better recruiter than Dooley. Herschel Walker has famously said that he made his decision to attend Georgia based on a coin flip. Meanwhile, Butts lured Rauch away from Tennessee, and landed Sinkwich out of Youngstown, Ohio, and Trippi out of Pottstown, Pennsylvania.

“In those days, you didn’t have scholarship limitations. And football in the South was less developed than it was in a place like Ohio. They had played it longer,” Smith said.

“He went North to find Sinkwich. The head of the legal department for the Coca-Cola Company was Harold Hirsch for whom the building the Georgia law school is in is named.”

By working with Butts, recruits such as Trippi would then get routes selling Coca-Cola, and this loyalty extended to a commitment to play for the Bulldogs.

So, if Butts is so influential to the game of football, as well as a tremendous recruiter, he must be the Bulldogs’ greatest coach ever, right?

Possibly, but let’s also examine the total Butts record. In the 1950s, Georgia fell on hard times before Tarkenton’s arrival. By 1949, it could be argued Georgia Tech had overtaken the Bulldogs for in-state supremacy, winning eight straight games from the Bulldogs as well as SEC titles in ’51 and ’52 and a Sugar Bowl wins in 1952, 1953 and 1955.

In 1953, behind future Green Bay Packers quarterback Zeke Bratkowski, the Bulldogs started out 2-0 and were nationally ranked. They finished 3-8. From 1955-58, Georgia experiences nary a winning season. One has to go back to 1903-06 to find four other consecutive losing seasons in Georgia history.

It’s true Dooley’s strategy was much more simplistic. He favored the running game, and in fact, when Herschel Walker won the Heisman Trophy in 1982, Georgia ranked last in the SEC in passing.

But consider when Dooley was hired, he was stepping into the mess created by the then-unsettled Post article and inheriting a team with three straight losing seasons.

Just three seasons later, the Bulldogs were SEC champions. Technically, they tied with Bear Bryant’s powerful Alabama squad, but so what? The point is during the height of Bryant’s success, Dooley was able to win six SEC titles.

So successful were the Bulldogs that in 1983, sportswriter Jack Chevalier wrote in The Sporting News that if Alabama and Georgia were made into an annual series, it would be bigger than the Iron Bowl.

What strikes everyone upon meeting Dooley is what a cerebral gentleman he is. With a master’s degree in history from Auburn, whom he played quarterback for in the 1950s, Dooley proved to be a professor’s coach, spending time in the library reading books when he wasn’t in the coach’s office.

Both Butts and Dooley served as Georgia’s athletic director following their coaching days, but Butts became something of a polarizing figure. Maybe it was the losing seasons at the end. Maybe it was some strained relationships with alumni after 22 seasons at the helm. Maybe it was the Post article, though the passage of time suggests the latter should not be a mark on the Butts legacy.

Dooley, meanwhile, was once so universally beloved he considered running for Governor of Georgia.

And in a state known for producing many modern political giants (Jimmy Carter, Sam Nunn), if Dooley had the right organization in place, it serves the question, “Who would have possibly beat him?”

Perhaps one incident late in Dooley’s coaching career revealed the true character of Dooley, as well as his coaching skill. In 1986, beating South Carolina 31-26 with four seconds remaining in Columbia, Georgia had the ball inside their own 30-yard line on fourth down. The decision was made to have quarterback James Jackson just run around in the backfield to run out the clock, rather than risk a punt return or block that could have given the Gamecocks a victory.

Jackson was able to do so, but then laid the football on the ground as the clock struck zero.

Under the rules of the time, the game was, in effect, over. Opponents could not return fumbles if they hit the ground.

Still, a Carolina defender eagerly scooped up the football and ran it into the end zone, thinking he’d won the game. Instead, he was only credited with a fumble recovery.

“Poor coaching,” Dooley told ESPN reporters without a hint of sarcasm when asked about the play on the field following the game.

Nobody was going to blame Dooley for Jackson’s cockiness. Dooley is just that revered a figure.

But by accepting the blame for such an unsportsmanlike play, though perhaps a fundamentally correct play (had Jackson allowed himself to be tackled, for instance, there was always the odd chance he could have been stripped of the ball and/or injured), Dooley was doing what a good coach does, taking the onus off of his player and placing it on himself.

Dooley has such stature that, for better or worse, heated rival Tennessee hired his son Derek to be their coach in 2010 after a modest tenure at Louisiana Tech instead of a higher-profile figure.

Think of it. Had Derek been successful, there would have always been the cloud of him going to Georgia if and when Mark Richt struggled. Coaches aren’t supposed to leave for division rivals, especially not Tennessee coaches.

What would it mean to the Vols if one of their coaches ever left on his own volition to Georgia? But the Volunteers were willing to accept this risk to be associated with the Dooley name.

New Georgia head coach Kirby Smart attended Georgia on the Wally Butts Scholarship that was instituted by Butts’ former players by raising $100,000 in his name.

Maybe if a Georgia fan could choose between the two coaches to guide the Bulldogs back from an in-game deficit, they’d choose Butts to call the plays.

But if the score is 0-0, they’d likely choose Dooley. As Smith says, “Vince is the most accomplished coach in Georgia history.”