Winning ‘war on football’: Startup programs often rely on SEC experience

Winning The War on Football

Startup programs often rely on SEC experience

by Marky Billson

Recently the media seems to have declared a “war on football.”

Articles in outlets from The Economist to the Huffington Post to even Grantland have theorized the sport must either be abolished or is nearing its inevitable end due to head trauma.

Yet 66 four-year colleges and universities, from FBS to the NAIA, have started football programs since 2000, while only 26 have dropped the sport. Three others, Alabama-Birmingham, East Tennessee State, and Division II New Haven, dropped football only to revive it again.

At the Division I level, when these schools decide they want a football program, often they look to the Southeastern Conference.

Georgia State and Southeastern Louisiana hired former SEC head coaches in Bill Curry and Hal Mumme, respectively, to pilot their new teams. South Alabama hired former Alabama receiver Joey Jones to be its head coach. East Tennessee State (revival) and Kennesaw State (start-up) asked Phil Fulmer and Vince Dooley for guidance. And Texas-Rio Grande Valley is conducting a feasibility study to revive the sport behind athletic director Chris King, formerly Alabama’s director of compliance.

“It is a rallying point for your students and alumni and community,” King said when asked why a college should have a football program. “We have 29,000 students. A decade from now we will have 40,000. We find it as a way to bridge the Upper and Lower Valley, as well as the alumni.

“We want to provide a national profile in the future. One is our school of medicine, but the second is football.”

UTRGV campus locations span 64 miles from Edinburg (Upper Valley) to Brownsville (Lower), a densely populated though isolated area deep in South Texas. It ranks as a larger TV market (87th) than Baton Rouge and El Paso, and its proximity to South Padre Island makes it something of a tourist draw. Linguists believe America’s next distinctive accent will come from the Rio Grande Valley, where Mexico meets the United States.

The 2013 merger of Texas-Pan American and Texas-Brownsville created UTRGV. But it lacks the identity of other state universities that field a collegiate teams in a certain sport.

“It’s the state of Texas. Football is king in the state,” King said. “Conferences, other than maybe the Big East, don’t look at universities that don’t have football.”

An indication that UTRGV is looking to leave the Western Athletic Conference it recently joined? Perhaps not. The Vaqueros could play football in the FCS or in another conference like WAC member New Mexico State. King even theorized the conference could restore football.

An enrollment boost

If UTRGV does start a team, it will follow a recent trend of colleges with high enrollment figures.

Take Georgia State. For now it is second-largest university in the Peach State with a 2015 enrollment of 32,052, roughly 4,000 students less than the University of Georgia.

But that could change.

“We are going to blow them out of the water,” said Charles Gilbreath, Georgia State’s director of institutional research. “We have absorbed Georgia Perimeter. We’re going to be at 50,000 students next year.”

Meanwhile in Johnson City, Tenn., the East Tennessee State Buccaneers re-started their football program last year after a 12-year hiatus.

When ETSU dropped football after the 2003 season, it received 3,825 first-time freshmen applications. In 2004, the school’s first year without football since World War II, it received 3,391 applications, a drop of more than 11 percent. But in 2015, the Buccaneers’ first year back on the gridiron, ETSU received 7,977 freshman applications, up more than 40 percent from 4,728 in 2013.

For comparison’s sake, the university took in 4,280 freshman applications in 2007, when ETSU opened a pharmacy school.

“Pharmacy is a very narrow interest. Football has a broader appeal,” Gilbreath said.

SOUTHEASTERN LOUISIANA

HAL MUMME AND WOODY WIDENHOFER

The Southeastern Louisiana Lions once were a small-college power.

From 1946 to 1961, the program won seven conference championships, launched the career of eventual Ole Miss coach Billy Brewer and won eight games in ’80 and ’81. But success was short-lived, and the 1985 football season was the last of the 20th century for Southeastern.

“When football was abandoned we were in a very tough economic time in Louisiana,” said Randy Moffett, president of the university when the program was restored in 2003.

“I was at Southeastern for 32 years, the last seven as president. I was there when football was eliminated and was there during those years where we didn’t. But there was always an active group wanting to return football. The number one question was, ‘When will you bring football back?’”

A friendly sort who prefers “Randy” to “Dr. Moffett,” he gets complimented for his role in restoring the program. But it was his predecessor, Dr. Sally Clausen, who initially decided to revive it in 2001.

“We made a decision that if we could raise $5 million in private money in one year we would return football,” said Moffett, who like Clausen later became president of the Louisiana university system.

Clausen left Southeastern for her new position in the middle of the fundraising campaign — after Wayne Dugas and Calvin Fayard both gave sizeable donations to meet 40 percent of Southeastern’s fundraising goal. Moffett continued the campaign as an interim and later a full-time president, finally announcing in the spring of 2002 that football would return the following year.

Time was short and only two members of the department, athletic director Frank Pergolizzi and athletic trainer Robert Goodwin, had been around football.

Enter new head coach Hal Mumme, who resigned from Kentucky the year before amid NCAA violations focused mainly on his recruiting coordinator.

“Coach Mumme was looking for an opportunity to reignite his coaching career and I was looking for someone who would put people in the stands,” Moffett said. “We needed a cannon shot, not a BB gun.”

Widenhofer, meanwhile, had been fired as Vanderbilt’s head coach following the 2001 season. He was out of coaching and receiving a buyout from the Commodores.

“I wasn’t ready to retire yet,” Widenhofer said. (Defensive coorinator at Southeastern Louisiana) was one of the jobs offered to me. And I had a lot of respect for Hal from when I was at Vanderbilt and he was at Kentucky. He scored a lot of points. He threw the ball on every play. I thought I’d give it a shot and went down there and enjoyed it very much.”

Widenhofer came to fame as the “Steel Curtain” defensive coordinator of the Pittsburgh Steelers during the franchise’s then-record fourth Super Bowl championship in 1979-80. Mumme was the offensive mastermind who helped quarterback Tim Couch become the first pick of the 1999 NFL draft. Southeastern got top offensive and defensive strategists with SEC head coaching experience.

“We were fortunate with the initial hires because of the two names,” Moffett said. “But the announcement of Mumme changed our plan because some teams backed out on their scheduling commitments.”

How does one start a program in one year?

“Some people take two (years), but that can be tedious,” Mumme said. “What you don’t think about when you start up a program is they don’t have anything, from paper clips to uniforms. All the things that must be done are unique.”

Moffett had to go to the local sporting goods store to buy a football and ask them to make a makeshift helmet with an unofficial logo for the press conference announcing the program. The sports information staff tracked down the bios of the dozens of rather unknown players and researched the program’s history for the media guide. The financial aid department found themselves with an influx of new students.

When the fall semester started, the program put up flyers asking the student body to try out for the team, to be joined by 25 scholarship players per year until the program reached the full FCS allotment of 63. Approximately 400 men showed up, pushing back tryouts to October.

“Our compliance director, Gary Harrod, was used to running the eligibility of 14 volleyball players. Now he had 400 football players to worry about,” Mumme said.

Fortunately the Lions still had Strawberry Stadium, built in 1937 as a Works Progress Administration project and still in use as a high school stadium. But it needed upgrades.

Mumme found himself dishing much of the recruiting responsibilities to his assistants as he took care of administrative duties.

“Louisiana high school football is phenomenal. There’s a whole lot of players within a hour’s drive of Southeast. It’s fairly easy to recruit,” Widenhofer said. “There was an awful lot of respect [from players and their families] because they knew what you were.”

The strategy: Go after every competent player within a 200-mile radius of Hammond, La. Sure, Louisiana State could offer better competition. But Mumme and Widenhofer knew what it took to make the pros.

“The SEC is real selective,” Mumme said. “There are camps for 19 straight days. Seven thousand [players] would show up and you’d recruit 20 of them. Theoretically at Southeastern you’d recruit 200.

“Every kid who could win in that area we tried to recruit. We didn’t get many, maybe one in 50. But if they wanted to transfer later on you’d be the first they’d call.”

Without a full allotment of scholarship players and with 40 walk-ons, Southeastern won its first game, 22-17, against Division II Arkansas-Monticello. Mumme made his mark by leading Division I-AA in total offense and passing yards per game.

The Lions finished with a 5-7 record. Troy represented their first Division I opponent, and they lost by a 28-0 score. Season lowlights included an 87-27 loss to Southland Conference member Northwestern State. Highlights included impressive season-ending victories against Division I non-scholarship Jacksonville and Prairie View A&M.

Then Southeastern made national news.

One of the Lions’ walk-on players, Jason Alexander, enjoyed a brief period of fame for marrying Britney Spears for 55 hours at the start of the 2004 New Year. It wasn’t the Spears family’s only association with the program. They had been major donors for the restart effort and part of the program in its first incarnation.

“Lynne (Spears) was a cheerleader and Jamie (Spears) played quarterback at Southeastern,” said Mumme. In fact, Britney’s dad James Spears lettered for three seasons at Southeastern from 1971-73.

Alexander didn’t make it to the field in 2004, but the Lions finished with a 7-4 record. The highlight of the season? “Beating McNeese State,” Widenhofer said. “They had beaten us by 37 points [in 2003] but we beat them the second year there.”

Ranked No. 6 in Division I-AA, the rival Cowboys endured a 51-17 route in the second game of the season. The win propelled the Lions to their first national ranking. It was enough for New Mexico State to notice. The Aggies hired Mumme and Widenhofer to coach their WAC team in 2005.

Southeastern left the football independent ranks to become a full-fledged Southland Conference member the same year. Growing pains arrived when an overwhelmed compliance staff allowed multiple ineligible football and basketball players to play in 2006 and 2007, resulting scholarship restrictions the last three years.

No matter. Under head coach Ron Roberts, the Lions won the Southland Conference in 2013 and 2014.

GEORGIA STATE

BILL CURRY

For years, Georgia State University earned the backhanded compliment of “best kept secret in the South.” Despite vast enrollment, few outside of Atlanta heard of the school prior to 1997, when GSU hired Lefty Driesell to be its men’s basketball coach.

“Georgia State for much of its history was a commuter school. Lots of people got their bachelors from Georgia Tech and their masters from State,” said Allison George, assistant athletic director for the Panthers. “Hiring Driesell was the first time (we) were serious about athletics.”

The basketball team won three regular-season Atlantic Sun championships during six seasons with Drisell at the helm, earning the Panthers attention they’d never received.

Hmm.

“Starting in 2000, off and on people started talking about football. But we’re downtown,” George said. “There was a feasibility study in 2006-07 with town hall meetings. Dan Reeves was utilized as a consultant to gauge interest.”

To have a program worthy of playing in the Georgia Dome and for so many alumni and students — to create buzz — GSU needed a name coach. So the school called Bill Curry.

“I had decided I wasn’t going to return to coaching,” said Curry, who had last coached at Kentucky in 1996. “My wife and I had moved 34 times in my football career. We just agreed we weren’t going to do it.”

But he already lived in Atlanta.

“Georgia State called to find out if I was going to be interested,” Curry recalled. “My wife Carolyn has a PhD and a masters (degree) from Georgia State, and it became a famous conversation. She pondered and said, ‘It’s my alma mater, I don’t have to move, let’s give it a shot.’

“It ended up being a real educational experience. We’ve stayed close to the people at GSU.”

So much so that Curry still refers to the Panthers as “we,” and took great delight in their success last season.

Curry played for Bobby Dodd, Vince Lombardi, Chuck Noll, Don Shula and even Bear Bryant and Ara Parseghian in a 1965 college all-star game. He’d been at the helm of his alma mater, Georgia Tech, when it made the transition from independent to Atlantic Coast Conference membership. He won the SEC championship at Alabama in 1989.

But those schools, as well as Kentucky, had ready-made infrastructure.

“The most difficult thing for us was creating a culture without the facilities. We didn’t have a practice field, a locker room. We were literally meeting in vacant classrooms outside of campus. The students and faculty were supportive, but also a bit skeptical, which is understandable,” Curry said.

“Just to find a practice field, we’d drive up and down I-75 and 85 and ask high schools if we could borrow the field. We found Martin Luther King Middle School, four or five miles from campus, and they allowed us to re-grade the field.”

Today GSU uses a fully-functional, 165,528 square foot practice facility. It features conflicting urban views of the Georgia State Capitol and a Marta line once used for railroads during the Civil War.

While Curry had the name to recruit, his experience was that of attracting SEC and ACC players.

“One huge difference. It’s a major factor every year. The student-athletes, obviously, need to go to college, and most need to have a scholarship. They don’t come from families that are well to do, in some cases they might, but not many,” Curry said.

“You get commitments from players you believe are good enough. What you don’t know is what will happen at the eleventh hour. Chattanooga may come in. Or one of the big schools may take your kicker. And the players disappear. You cannot predict who will leave at the eleventh hour. We didn’t blame the kid or parents. If you have a choice between Georgia and Georgia State you’ll take Georgia.”

Still, Curry tried to drum up school spirit, literally. He arranged to have the newly-formed band march in downtown Atlanta. “That’s some of the stuff that comes along with having a football team. Real good chance if there isn’t a football team we wouldn’t have a band.”

On Sept. 2, 2010, Georgia State began its existence as an independent FCS team in front of more than 30,000 fans at the Georgia Dome with a 41-7 victory against Division II Shorter.

Photo Credit: Georgia State

The Panthers were able to forge a 6-5 record in their first season with victories against two Division I non-scholarship programs, two Division II teams, a fellow first-year program (Lamar) and traditional whipping boy Savannah State.

As the slate got tougher the Panthers fell to 3-9 in 2011, though they did avenge losses in their inaugural season to Campbell and South Alabama, the first defeat USA ever suffered to a non-FBS team. The Panthers then joined the Colonial Athletic Conference, perhaps the toughest conference in FCS football. Additionally, GSU scheduled two money games against FBS teams.

“Winning is mostly scheduling. You’re not Alabama, Notre Dame or Southern California,” Curry said. “That league which we moved into was just tough as nails. William & Mary, Villanova, Old Dominion; it was a lot tougher than I had anticipated.”

Said George: “We intended to be an FCS program. (But) with the conference expansion at the higher levels, there was an opportunity for us.”

Invited to the Sun Belt in 2012, GSU accepted. The team’s roster was recruited to compete at the FCS level, where the program had just advanced to the full compliment of 63 scholarships. Now the limit changed to 85, but the team could only sign 25 scholarship players per year.

“The opportunity to go FBS was not going to be repeated if we didn’t do it then,” Curry said.

Curry retired after the Panthers finished 1-11 in 2012, with only a midseason 41-7 victory against 0-11 Rhode Island. The Panthers only won one more game until 2015.

Then the Panthers achieved a major milestone under head coach Trent Miles. They won their final four games of the regular season, all against Sun Belt foes, to even their record at 6-6 and earn an invite to the first-ever Cure Bowl in Orlando, where they fell to San Jose State, 27-16.

With talk of converting Turner Field into a 30,000-seat Georgia State football stadium once the Atlanta Braves leave after this season, there may be even more room for growth. If the Big 12 expands and plucks a current American Athletic Conference or Conference USA member or two, who is to say the new facilities and improved team, let alone market size, school size, and alumni base won’t make GSU an attractive replacement to the American or C-USA?

Such a move would correspond with the growth of GSU as a whole. When Driesell came the university had 24,300 students. Georgia State likely will double that amount after the merger with Georgia Perimeter is complete.

“Georgia State has literally saved downtown Atlanta,” Curry said. “They bought the buildings. Refurbished them. Turned them into offices and classrooms and labs. Wonderful old buildings have been saved from demolition or vacancy because of that.

“A lot of people are moving back downtown because they are sick of coming in from Alpharetta … Now we’re less of a commuter school. GSU graduates more minority candidates than any other school in America.”

Curry credits Dodd and assistant John Robert Bell at then-SEC member Georgia Tech for teaching him the principles he’s passed along and turning him from a fourth-string lineman to a 10-year NFL veteran.

“Dodd told us ‘I’m a third quarter sophomore at the University of Tennessee. I’m 53. That’s not going to happen to you,’” Curry recalled. “The most important thing is the young man and his education. The most important thing to Dodd was perfect class attendance and tutoring. If a player doesn’t get his education, you’ve cheated the students.

“We had Saturday classes. I remember playing Alabama at 2 o’clock. Still better be in class and go get suited up and play.”

For now, Curry is still the only coach to post a winning record at an advancing program.

KENNESAW STATE &

EAST TENNESSEE STATE

VINCE DOOLEY & PHIL FULMER

Last Sept. 3, the fruits of the labor of Vince Dooley and Phil Fulmer met on the gridiron again.

They weren’t coaches anymore, but they had a major influence on the game. They were representing teams from Georgia and Tennessee, but they weren’t representing the Bulldogs and Volunteers. This time, Dooley and Fulmer converged inside a high school football stadium in Johnson City, Tenn., for Kennesaw State-East Tennessee State. The venue held 8,000 fans, not 90,000

Scalpers sold tickets for more than $100.

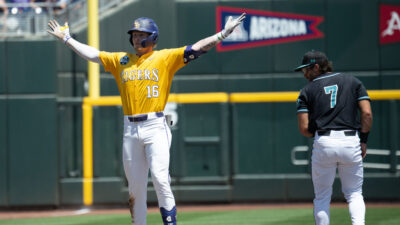

Photo Credit: Kyle Hess/KSU Athletics

“I think it was a surprise to everybody,” Dooley said of the game between two new FCS teams. “Including me, and I was there. I even had the chance to say hello to Coach Fulmer, and I was familiar with ETSU because one of my former quarterbacks, Mike Cavan, had coached there and I’d even spoken at their banquet.”

The story of ETSU’s football revival began when it dropped the program following the 2003 season.

Underfunded, the Buccaneers played in an indoor stadium criticized by locals for poor sightlines.

University president Dr. Paul Stanton faced little criticism for his decision to drop the ETSU football program, citing his unwillingness to implement a student activities fee to continue funding it. Hardly viewed as an Art Modell for this move, Stanton is now commissioner of Washington County and won the Republican primary for the County Commission’s 6th District seat last March.

But, as was the case at Southeastern Louisiana, a group led by ETSU’s former athletic trainer Jerry Robertson tried to restore football almost as soon as the program folded. They succeeded in pushing the issue to a student vote in 2007, but the students decided not to pay for an additional activities fee, and the effort failed.

Yet the group continued to meet and hold annual golf outings, and when Brian Noland succeeded Stanton as ETSU president in 2012, the idea found traction. A year later, the vote to raise activities fees to fund the program went through student government, not the students directly. It passed, 22-5.

“It was a deepening of connections with the community,” Noland said of football’s revival. But how to restore a program from scratch? “My joke was, ‘I don’t have a lot of experience in starting programs. I closed a program at West Virginia Tech.'”

Enter Fulmer. Though he had no previous ties with ETSU, Johnson City is only 100 miles north of Knoxville. A founding partner at BVP Capital Management, he also had the desire to return to football in some capacity.

“The thing that he brought to the table was just his rich set of experiences, connections, and understanding of the complexity of football in American athletics,” Noland said.

Said Fulmer: “They asked me to get on board because I would know a lot of the coaches. There’s a big difference in starting a basketball team and football. So many more players and equipment. It’s just a bigger production.”

Meanwhile, Kennesaw State, a suburban Atlanta university, had grown to 33,252 students by the time the football team started play. Still, the profile lagged. The Owls had only been a Division I program since 2005, and the college itself had only been around since 1963.

Dooley, the famous former head football coach and athletic director at Georgia, came to serve as a multi-tasking consultant.

“The president along with vice president of advancement had discussed it and asked if I would join them to explore the possibilities to have football,” Dooley recalled. “There was a cross section of interested people in the university.

“I wasn’t just a fund raiser. I think the primary job was to chair an exploratory committee, which consisted of about 33 people — students, faculty and business community people. We divided into four subcommittees. After a seven- to nine-month study we made a recommendation to [KSU President] Dr. [Daniel] Papp that he should explore the start-up of football.

“From there, I just consulted with the athletic director who was hired, and that’s Vaughn Williams, and also with the coach Brian Bohannon and attended many of the functions at KSU as they proceeded in a very deliberate way in starting football again.”

Bohannon is a former Georgia Bulldogs receiver (1990-93) and an assistant at Georgia Southern, Navy, and Georgia Tech under Paul Johnson, whose influence upon him is strong. KSU led the Big South in rushing last season.

Fulmer also was instrumental in hiring the Buccaneers’ head coach, Carl Torbush, who previously served as defensive coordinator at Ole Miss (1983-86), Alabama (2001-02) and Mississippi State (2009).

“We must have interviewed 50 guys, either on the phone or otherwise, until we got down to the five we brought in,” Fulmer said. “About half the people said, ‘I will hire Carl Torbush as my defensive coordinator.’”

Why not make him the head coach, then? Torbush, coaching Liberty’s linebackers at the time, previously found work as North Carolina’s head football coach (1998-2000) and ironically had started in college coaching as an assistant under Billy Brewer at Southeastern Louisiana.

“He was part of the interview process,” Noland said of Fulmer. “He helped bring to the institution Carl Torbush. If it wasn’t for him, (Torbush) wouldn’t be there.”

The Bucs then lured Billy Taylor, ETSU’s defensive coordinator when the program was dropped, to return from Tennessee Tech to his old position. Former North Carolina State head coach Mike O’Cain became offensive coordinator. Native son Teddy Gaines, a defensive back on the 1998 national championship Tennessee Volunteers, came to coach the safeties.

Torbush took an unorthodox approach to building the Buccaneers program. He disdained junior college transfers and instead opted to stack his roster with true and redshirt freshmen.

Overwhelmed, ETSU not only dropped their opener to KSU by 40 points, but lost by at least 40 to five of their opponents in 2015, finishing 2-9. The Bucs managed victories only against Warner and Kentucky Wesleyan, a Division II school with approximately 700 students.

“He wasn’t looking for a quick fix,” Fulmer said. “You can argue a bit more maturity would have helped, but that wasn’t the foundation. You have to respect that.”

Kennesaw State, playing with three transfers in the backfield, finished 6-5 through a full Big South schedule, including victories against conference foes Garner-Webb and Monmouth.

“It was about a five-year process, but by doing that they were able to cross all their T’s and dot their I’s,” Dooley said. “At least $10 million are needed for a start-up.”

Dooley lends credence to football fundraising efforts in Georgia, though he is modest about his influence.

KSU sold naming rights to Fifth Third Bank, refurbishing its soccer stadium to seat 20,000 fans. But ETSU needs $23 million for its new football stadium, which is still in the initial stages of construction.

Dooley is a part-time consultant as he prepares to become the Chairman of the Board of Curators at the Georgia Historical Society. Fulmer is more hands-on, visiting ETSU two or three times a month to help with the funding structure.

Kennesaw State may be a prime candidate for “trickle up” status.

But Dooley warns against growing too fast, too soon.

“The great thing of consulting is you can give your opinion, you don’t make a decision,” Dooley said. “I think it’s a nice way to stay involved but not with the day to day intensity. I still am involved and enjoy the good benefits.”

ETSU has scheduled football games with Tennessee in 2018 and Vanderbilt in 2019, along with longtime rival Appalachian State. This is the last year they are scheduled to play their home games at a high school. They’ll even play a game at 160,000-seat Bristol Motor Speedway against Western Carolina the week after Tennessee-Virginia Tech.

“They look like a good football team. You can just tell. They are bigger and stronger and some nice-looking guys who weren’t in practice before,” Fulmer said after observing ETSU in spring practice. “They will go to another level joining the Southern Conference.”

SOUTH ALABAMA

JOEY JONES

If there’s a textbook way to start a football program, one might look to South Alabama. After all, the Jaguars won the first 19 games in their football history.

South Alabama did not play a tough schedule. In 2009 it played seven games, all at home, against prep schools and junior colleges. The following season USA played only three Division I foes, including two in their first season back on the gridiron. By the time USA lost a game, it already was an FBS member.

Though the Jaguars haven’t been able to retain an unbeaten record, crowds of more than 20,000 fans are not uncommon at Ladd-Peebles Stadium. Fans have witnessed home games against the likes of Navy, North Carolina State and even Mississippi State. They’ve seen their team join the Sun Belt Conference and go to the 2014 Camilla Bowl.

And the one constant through all this time? Head coach Joey Jones, whose résumé reads like Alabama football royalty.

As a first-year redshirt, Jones was a member of Paul “Bear” Bryant’s last national championship team in 1979. At 5-foot-9, he averaged nearly 20 yards a catch as a three-year starter and earned All-SEC honors as a senior. The Atlanta Falcons selected Jones in the first round of the 1984 NFL draft. Instead, he signed with the Birmingham Stallions, making acrobatic catches on two USFL playoff teams before ending his pro career with the Falcons in 1986.

Photo Credit: South Alabama Athletics

He still implements many of the lessons Bryant taught him. Not that Jones coaches USA from a tower, or duplicates some of the Bear’s more extreme coaching methods.

“You’d have a ‘gut check’ practice, which meant tough as hell,” Jones recalled. “I remember being in a scrimmage for 64 plays in a row as a receiver. I think they forgot about the receivers out there, all they cared about was running the football. I wanted to quit a couple, three times. But when I went through it, I realized everything else would be easier.”

South Alabama isn’t the first start-up program Jones has coached. He previously guided Division III Birmingham Southern to a 3-7 record in its first football season since 1939. But the Panthers had dropped down from Division I ranks the year before. South Alabama wanted to get there.

“When I took the job, I had several meetings (concerning) how fast we wanted to be a D-I program. We wanted a four-year plan,” Jones said. “I thought it was a good progression. A lot of schools had gone longer.”

In Jones’ fourth year, USA joined the Sun Belt, finishing with a 2-11 record. The following season, the Jaguars gave Tennessee a scare by marching to the Vols’ 7-yard line in the final two minutes before falling 31-24, and then routed Kent State to finish 6-6. In 2014, the Jaguars went to their first bowl game. Last season, USA fell to 5-7 with a schedule that included Nebraska and North Carolina State, but still enjoyed a 34-27 victory against Mountain West champion San Diego State.

“To get where we wanted to be we had to play the best teams possible,” Jones said.

Back to Bryant and those early lessons. To many in Alabama, Jones’ background is important.

“It comes up often,” said Jones when asked if Bryant’s name comes up on recruiting trips. “Most of the time from the parents from that era. They often tell the son, ‘Hey, this is a coach who played for a legend!’”

“(Players) ask questions. ‘What kind of person was he?’ I always have a story to tell if they ask,” Jones said. “I think that No. 1 the thing we believe in is being accountable to each other, and to the staff and the players. Accountability is a big deal. I learned that at Alabama. I learned that from Coach Bryant.”

Jones knows he dares not revive “The Junction Boys,” even if he wanted to.

“Right or wrong it’s different,” Jones said of modern practices. “Rightfully so. The safety of the student-athlete is number one. Not tackling as much in practice. Not pushing them quite as hard. We find other ways. You have to adjust with the times. Some things now are good for the player.”

For instance, for one day every year Jones invites a Navy Seal to talk to the team.

“They’re able to push the players a bit farther. They create teamwork and do some things we probably didn’t know how to, but they understand when a kid is pushed too far. They know when to back off.”

Jones does institute one policy that might be thought of as exceptionally tough: The 5:30 a.m. practice. It not only “teaches kids discipline and gets the ball rolling,” it keeps reporters away from the practice field and frees up the day for South Alabama players.

“Our kids can start any class after 10:10 a.m.,” Jones said. “There are a few kids that have to go to an 8 a.m. class, but they go to class over practice. We work around that. But 99 percent of the time there are no conflicts.”