Film Study: Alabama’s menacing defense redesigned to destroy

By Matt Hinton

Published:

A weekly look inside an SEC playbook.

News flash: Alabama’s defense is good. Like, really good, in all of the predictable, tried-and-true Bama ways (surprise, the Crimson Tide rank No. 1 nationally against the run), and lately in a few not so familiar ways, too. It’s so good lately it’s turning the old line, “the best defense is a good offense” into a literal mission statement. What if the best defense actually is a good offense, entirely on its own?

While it’s not quite true that the Bama D is outscoring its opponents by itself — not yet, anyway — it’s not far from it, either. Through six games the defense has allowed 10 touchdowns and scored seven, four on fumbles and three on interception returns; add in special teams touchdowns, and the Tide could have outscored four of their six opponents to date without the actual offense setting foot on the field.

Non-offensive touchdowns supplied the decisive margin in a come-from-behind win at Ole Miss, opened up the floodgates in lopsided romps over USC and Kentucky, and slammed the door on Arkansas. Eight defensive players have gotten on the board already, and we’re barely halfway through the regular season.

For most teams, even ones as monolithically talented as Alabama, that kind of run would amount to a curiosity, a confluence of opportunity and luck, and not much more. For this particular team, though, a fully self-sufficient, point-neutral defense isn’t just a coincidence: It’s part of a deliberate evolution that is changing the image of Alabama from a team full of steady, disciplined cogs in a machine into an enterprising, ball-hawking unit in which almost anyone has a chance to rise above the fold.

The streak (now at eight games and counting, dating to January’s Cotton Bowl massacre of Michigan State) began with a concerted effort to get better at getting after opposing quarterbacks. Where it will end is anybody’s guess.

Reinventing the defense to create havoc

Over the years Nick Saban’s defenses have consistently ranked among the nation’s best in every category except one: Rushing the passer.

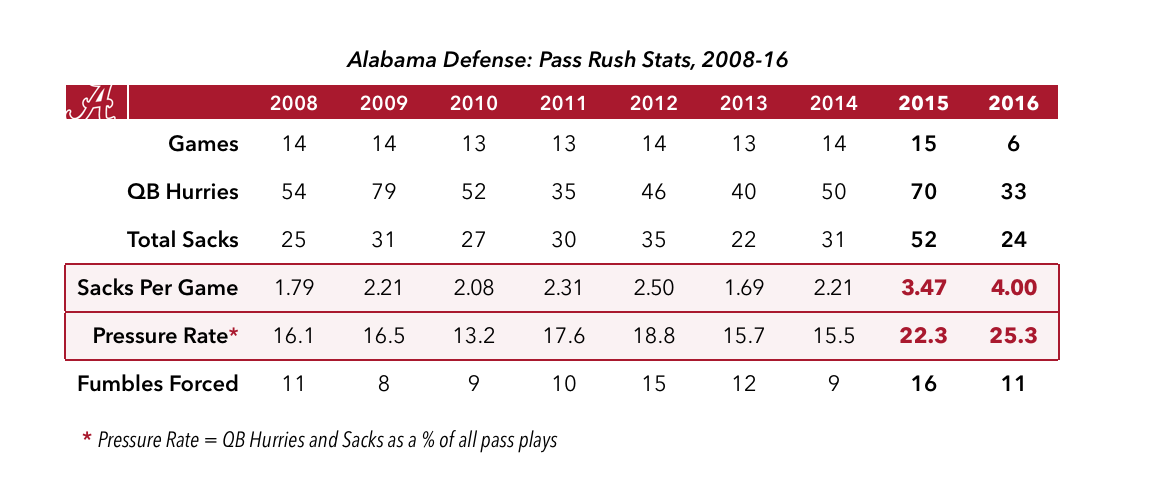

In Saban’s first eight seasons at Alabama (2007-14), the Crimson Tide never finished in the top 25 in sacks per game, and outside of the historically dominant units that anchored national championship runs in 2011 (29th) and 2012 (28th), it didn’t come close.

Partly that was by design. At its root, Saban’s base 3-4 defense was engineered to stuff traditional offenses by playing sound gap assignments against the run, preferably without asking a safety to serve as the eighth man in the box. That meant less emphasis on creating pressure or penetration in the backfield than on big, immovable bodies occupying blockers and clogging running lanes. The general effect in those years was of a wall being erected at the line of scrimmage, not a wave of rushers crashing over it.

By 2014, however, the proliferation of spread offenses in the SEC had begun to poke holes in that blueprint. From 2009-12, Alabama allowed 30 points in a game only once en route to three BCS titles in four years. By contrast, opposing offenses in 2013-14 broke the 30-point barrier five times, and Bama came up short of the title game both seasons.

Not coincidentally, those campaigns also marked a new low for both the pass rush and its ability to create turnovers: 2013 yielded Saban-era lows for both sacks (22) and takeaways (19); the ’14 team ranked a dismal 92nd in Adjusted Sack Rate and finished in the red in turnover margin (-2) for the first time in Saban’s tenure.

In that context, 2015 was a revelation — for all the ways that last year’s championship run felt like a return to vintage Bama, by any measure the pass rush left even its most decorated predecessors in the dust. From the lower rungs of the national rankings the Tide leapt to the top in a single bound, finishing with the national lead in total sacks (52) and Adjusted Sack Rate.

In sacks per game, they improved from 60th in 2014 to third. Prior to last year, Saban had never had an individual player at Alabama with double-digit sacks in a season; in 2015, he had two, Jonathan Allen (12) and Tim Williams (10.5), both of whom seemed to emerge from nowhere, fully formed, as the best pure edge rushers at Bama in at least a decade. (Aside from Courtney Upshaw, I’m not sure who else is even in that conversation.)

In an alternate timeline, Allen and Williams would be making millions in the NFL right now, where they rightfully belong. Back in reality, they’re on pace as seniors to eclipse last year’s breakthrough with ease:

So far, Alabama has racked up more negative yards on sacks (191) than any other FBS team, and the cumulative effect has been more dramatic than the Pressure Rate statistic in that chart indicates. Measuring “pressure” is always somewhat subjective; for example, although QB Hurries is usually listed in official box scores, there’s no standard from one stat keeper to the next outlining what qualifies as a “hurry,” and no way to know how consistently the category is even recorded.

Based on my own review, though, Alabama has pressured opposing passers at a much higher rate than 25 percent: In their four games against Power Five opponents (USC, Ole Miss, Kentucky, and Arkansas), that number is closer to 50 percent — by my count, out of 171 dropbacks in those games (not including screen passes), 81 resulted in a hurry, hit, sack, or holding penalty against the offense.

In last week’s win over Arkansas, the number was even higher; Razorbacks’ QB Austin Allen dropped back to pass 59 times and was pressured, hit, or sacked 34 times.

Again, although the personnel is better suited to generating heat off the edge than its more run-oriented predecessors, the steady increase in pressure is also by design. According to Pro Football Focus, Bama is blitzing significantly more often under first-year coordinator Jeremy Pruitt than it did even last year, when the Tide sent an extra rusher just 19.5 percent of the time. (The national average is a little less than 30 percent.) Against Arkansas, PFF calculated Alabama’s blitz rate at a whopping 48 percent.

Frankly, with the capacity the front four has to get to the quarterback all by itself that number seems like overkill. (Presumably Austin Allen agrees.) Beyond the raw numbers, though, blitzing can create opportunities for favorable one-on-one matchups that might not exist otherwise, and occasionally free up rushers for a free run at the quarterback unopposed.

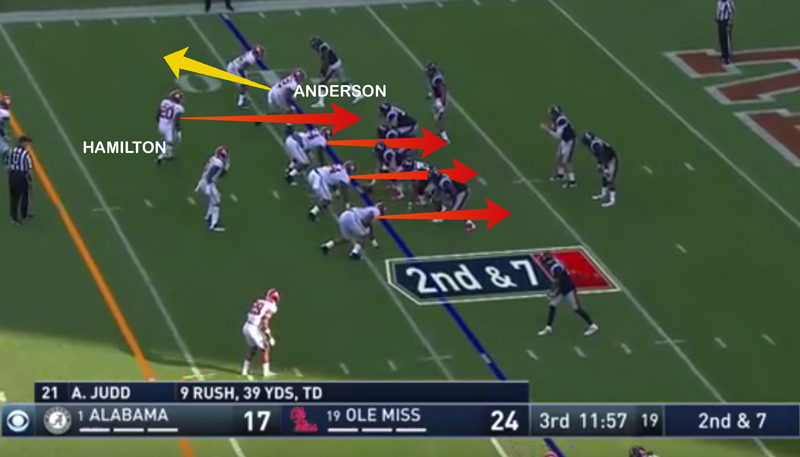

Take this play against Ole Miss, where Alabama showed the Rebels a three-man line with outside linebacker Ryan Anderson (No. 22) in position to rush off the edge. Instead, at the snap Anderson will initially drop into coverage against Ole Miss’ best receiver, tight end Evan Engram (17), while the blitz comes from inside linebacker Shaun Dion Hamilton.

At the snap, this looks like a standard four-man rush with Anderson dropping into the flat; quickly, however, Anderson changes the math by abandoning Engram and chasing after quarterback Chad Kelly on a delayed blitz from the outside. Hamilton’s role on this play isn’t to find an opening himself, but to occupy the Rebels’ right tackle, Sean Rawlings (No. 50), just long enough for Anderson to turn the corner. Which he did, with dramatic results:

The touchdown was credited to Da’Ron Payne, but it really belonged to a) excellent coverage downfield, forcing Kelly to hold onto the ball to the point that he wound up in a Jaws-like situation everyone in the stadium could see coming except him, and b) a play design that freed up one of the best rushers in the SEC for an unimpeded path to the quarterback. Remember that, because Ole Miss’ line certainly did.

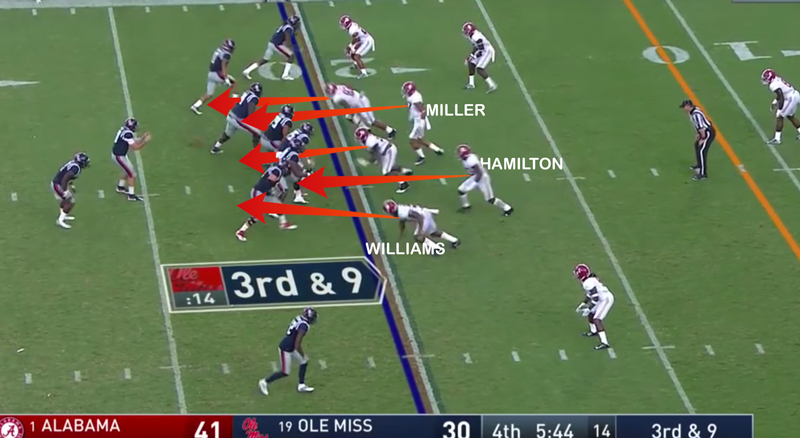

Cut to the fourth quarter, Rebels driving for a potential score that will cut Alabama’s lead to single digits and keep the game theoretically within reach. Again, at the snap the Tide show a five-man rush with two middle linebackers, Hamilton and Christian Miller (No. 47), threatening a blitz over Ole Miss’ respective guards:

More kabuki: This time, Hamilton quickly abandons his initial rush action to pick up a back releasing out of the backfield. Still, without even engaging with the Rebels’ right guard, Jordan Sims (70), Hamilton has already established himself as a enough of a threat that his feint is enough to grab Sims’ attention; thus occupied, he’s too slow to help out Rawlings with a double team against Tim Williams (56) off the edge. One-on-one in an obvious passing situation, that matchup is not even fair:

In the end, that was only a three-man rush. But by forcing the offense to brace for more, Alabama was able to get its most explosive edge rusher in ages isolated on a blocker who had almost no hope of slowing him down alone. And it did it without sacrificing anything in coverage.

Keep Austin Wired

Over time, the pressure begins to add up mentally as well as physically. As mentioned, the last time we saw them the Crimson Tide front beat Arkansas’ Austin Allen to a quantifiable pulp in Fayetteville, hounding him so relentlessly that he eventually began to react as if he was under duress even on the few occasions when he had plenty of time.

Here’s the first of three second-half interceptions Allen served up against Bama, all to sophomore cornerback Minkah Fitzpatrick. On this one, he obviously does not have time — Dalvin Tomlinson (No. 54) exploits a protection bust on the interior line and is in Allen’s face immediately, forcing him to heave a hopeless, off-balance prayer just to avoid a safety.

That was strictly reactive to avoid disaster; Allen had no chance to scan the field, set his feet, or do any of the fundamentally sound quarterback things he’s supposed to do, and no choice but to throw the ball away. You could plausibly make the same argument for his second interception, just a few minutes later, on which he had more time but still wound up sailing an off-balance prayer over his receiver’s head as Ryan Anderson closed in for another free shot. (Nothing cerebral going on here: Just Anderson blowing by the right tackle on 4th-and-10, another obvious passing down.)

On his third pick, though, early in the fourth quarter, Allen had time to throw and room to maneuver in the pocket. (Tomlinson gets another strong push here up the middle, but is effectively ridden upfield and out of Allen’s throwing line by the left guard, Hjalte Foholt, No. 51.) Instead, at the first hint of pressure Allen sailed another arm punt into traffic as if he was bracing for impact, and Alabama had another coast-to-coast, game-clinching pick-six for posterity.

You wouldn’t know if from this sequence, but Allen actually did a lot of good things in this game, too, ultimately throwing for 400 yards and three touchdowns. Once a quarterback’s internal clock is wound this tight, though, it’s only a matter of time before it starts going off when it shouldn’t.

To Saturday and Beyond

For a statistic that everyone agrees is crucial to winning and losing, turnovers are notoriously random and impossible to predict from one week to the next. So the fact that Tennessee just committed seven giveaways in last week’s wild, double-overtime loss at Texas A&M — more than any FBS team in any other game this season — doesn’t necessarily mean the Vols will continue their butterfinger-y ways against Alabama or anyone else over the back half of the season.

In fact, through its first four games Tennessee had incredibly good luck with regard to recovering loose balls. These things tend to even out over time. So who knows? After last week, the turnover pendulum might be due to swing back in UT’s favor.

If anything, Tennessee should be much more concerned with the four sacks and five QB hurries it allowed against A&M, which contributed directly to several of the giveaways. (By the end, Joshua Dobbs might have been seeing a ghost or two himself on the decisive interception that ended the game and Tennessee’s unbeaten season.) Protecting Dobbs has been a recurring problem right from the start, and it won’t help that he’ll be down at least one starting offensive lineman Saturday.

On the other hand, Alabama’s is hardly invulnerable — when not being harassed into multiple, game-killing mistakes, both Chad Kelly and Austin Allen put the secondary to the test.

Despite its own inconsistency, Tennessee’s offense has grown more explosive by the week; the top two receivers, Josh Malone and Jauan Jennings, are averaging more than 18 yards per catch between them, and Bama transfer Alvin Kamara was an all-purpose revelation against the Aggies in the absence of the usual workhorse, Jalen Hurd. (All indications are that Hurd will be back this weekend.)

Alabama has allowed a dozen plays of 30 yards or more, most of them in just the two games against Ole Miss and Arkansas. If the Vols are able to get Hurd going between the tackles (he ran for 92 yards on 5.1 per carry last year in Tuscaloosa), there will be opportunities to strike downfield, a la Ole Miss when the Crimson Tide got a little overaggressive against the run in Oxford.

But the blueprint always works until you actually have to block it, and in this case blocking Alabama is always a down-by-down, series-by-series proposition.

Over four quarters the Tide are going to inflict some damage; meanwhile, the Vols have yet to put together a single complete, compelling effort over four quarters this season.

The Vols have already endured just about every plot twist a season can throw at a team and somehow survived with all its larger goals still intact. But if they can’t make it through the afternoon without a Bama defender taking it in the opposite direction then the list of teams that conceivably can will keep getting shorter by the week.

Matt Hinton, author of 'Monday Down South' and our resident QB guru, has previously written for Dr. Saturday, CBS and Grantland.