By Oliver Connolly

In the summer of 2013, the best minds in the NFL were tasked with a new, seemingly impossible, question: How do we stop the spread-option?

The league was coming off a year in which young quarterbacks like Russell Wilson, Colin Kaepernick and Robert Griffin III had devastated defenses again and again with the ability to carve them open on the ground behind offenses that had a numerical advantage in the box.

That same question plagued high school football 15-years earlier, and college football for the past decade.

Teams at all levels were placing their best athlete behind center and implementing varying elements of the spread-option; zone-reads, designed quarterback runs, triple-options, run-pass options and doing it all at warp speed.

In that summer of 2013 (with the future of the three aforementioned quarterbacks unknown) the league with the greatest football minds in the business set out to try and solve the riddle. Do we attack the mesh-point? Hit the quarterback on every play? Use more overload looks? Or rely on the unsustainability of the play as the basis of an offense for an entire game, season or career?

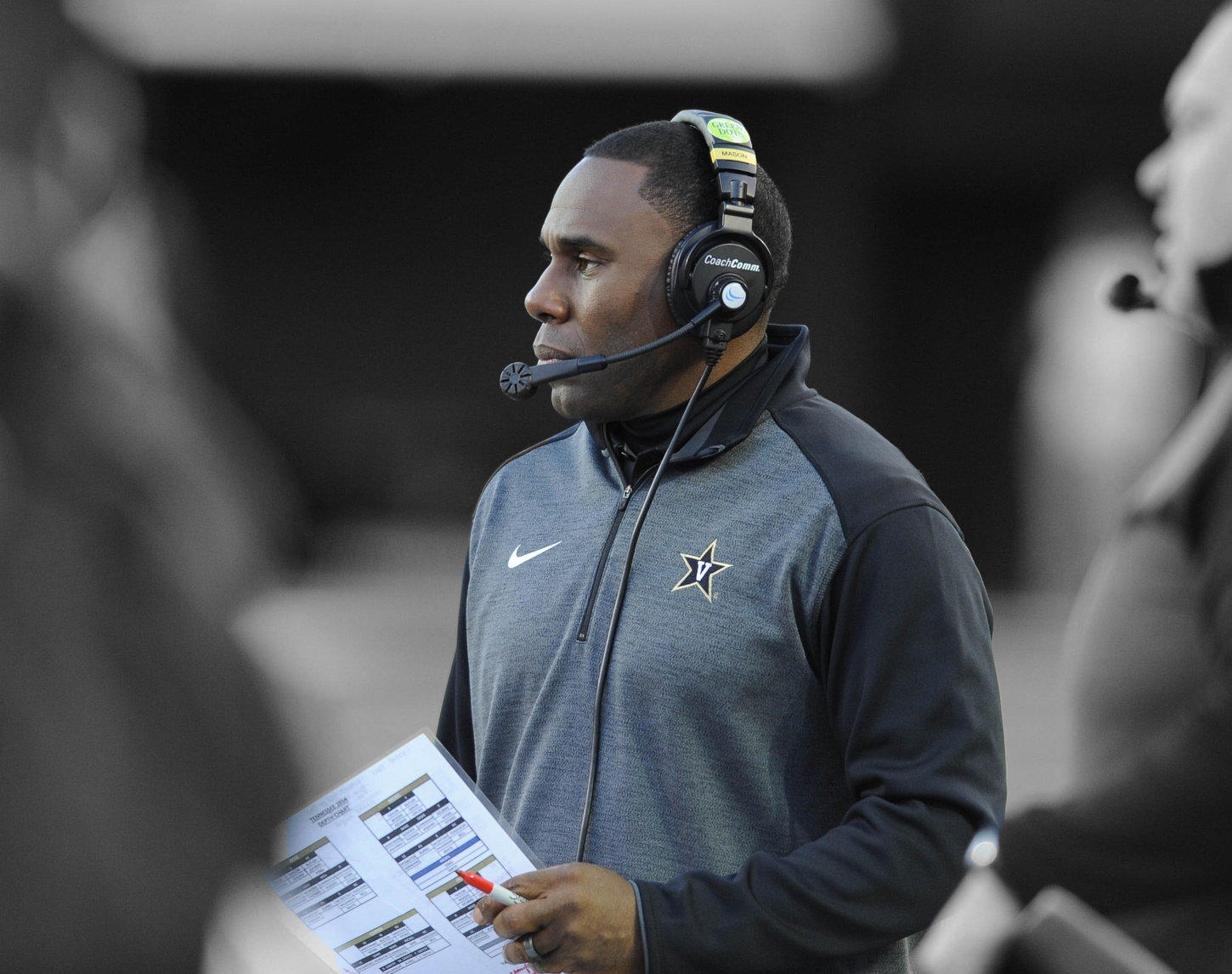

The league looked everywhere, from some of the best defensive minds in the country (Nick Saban), to those who had implemented the destructive plays offensively (Urban Meyer). But one man generated one of the largest crowds of that coaching clinic summer: former Stanford defensive coordinator, now Vanderbilt head coach, Derek Mason.

Mason, a former college cornerback, made a name for himself by building a system that shut down the potent Oregon Ducks attack in back-to-back years. Talking heads said Oregon — and spread-option teams as a whole — succumbed to some good ol’ fashioned power football. But the might of the NFL knew better than that, and they wanted to meet with the man who had designed, and implemented, a defensive strategy that shut down one of the most explosive college offenses in recent memory.

***

In his first season as the Vanderbilt head coach the football team was, predictably, tragic. The Commodores had just come off a pair of successful seasons under James Franklin, but their roster was not built for sustained success.

Mason entered with the reputation as a defensive mastermind, and he brought a hybrid defense that featured differing defensive fronts. They included three and four man fronts, but remained a staunch two-gap unit.

***

Both sides of the football number the gaps at the line of scrimmage, the offense by numbers and the defense by letters — Bear Bryant is credited with inventing the gaps.

Teams will opt for either a one-gap or two-gap system depending on their defensive philosophy or personnel.

Traditionally 4-3 teams will use a one-gap system. Each defender is responsible for one-gap and takes care of their individual assignment. If there’s a blown assignment it is obvious where there was a mistake/mismatch.

The 3-4 schemes use a two-gap system. Lineman must be more disciplined as they’re responsible for two gaps and must read-and-react to the play, rather than flow immediately to their gap.

Each scheme has its positives and negatives, and the best defenses have begun to mix-and-match their schemes with more hybrid looks and responsibilities from non-traditional looks.

Building that at the college level is difficult; teams do not have the time, and the players aren’t as talented. But top programs like Alabama have opted to rotate their defensive front with each sub-package learning their own assignments. They’ll open up in a two-gap front to attempt to shut down the run, before unleashing a slew of pass-rushers who are one-gap and go players.

***

Why Two-Gap?

Mason believes in two-gap defenses at the college level. They are the best way to defend the read-option and attempt to shut down up-tempo spread offenses.

Spread offenses count defenders in the box and choose which to play to run based on the numerical advantage.

In Mason’s flexible two-gap, his defensive linemen are taught to hold their block and react to the ball. Ends set the edge and funnel plays inside to the linebackers.

Mason believes in two-gap defenses at the college level. They are the best way to defend the read-option and attempt to shut down up-tempo spread offenses.

In his first year at Vanderbilt he was more standoffish with the defense than one would assume. He balanced his time as the head of a program, rather than being the defense coordinator. The defense was a train-wreck and the school took a six-game tumble in the wins’ column, falling from 9-4 in Franklin’s last year to 3-9 in Mason’s first. They struggled in every area of the game and gifted an average of 402.1 yards per game.

Not exactly the work of a defensive genius.

Last season was much better; Mason fired his defensive coordinator and made himself the new DC. They finished 22nd nationally in scoring defense, 28th in total defense. They surrendered just 350.6 yards per game.

While their offense did not improve, and the win total only by one, Vandy saw a big upswing in its defensive play. In 2014 the Commodores were outscored by 22.6 points per game in league play, but that number fell to just under 10 in 2015.

What changed?

Mason’s system, like all systems, takes time to install and perfect — particularly when because it’s based upon decision-making.

Vandy sports a two-gap scheme, mostly out of a three-man front, in large part to defend against spread attacks. With spread offenses playing a numbers game — counting defenders in the box and choosing which to play to run based on the numerical advantage — defenses are at a distinct numerical disadvantage. Even more so if you add in the threat of a quarterback who can run.

To counter this, Mason has built a flexible two-gap system with some subtle adjustments and tweaks to try and claw back a numerical advantage against the offense.

It’s a defense that saw his Stanford teams shut down those explosive Oregon teams, and one that the NFL parachuted in to steal see. It’s also a defense that we’ve seen replicated around the country, including within the SEC.

In this year’s Athlon Sports College Football Preview Magazine, an anonymous SEC assistant coach said: “I’m not exaggerating when I say this: Derek Mason is as good of a defensive coach as there is in the world. …” The anonymous coach isn’t wrong. Sure, Saban remains the best defensive mind at the college level, and I’d put Pat Narduzzi right there, but Mason continues to innovate, evolve and has the top minds in the country arriving at his doorstep to figure out some of the things he is doing.

Respect the numbers game

Offenses that feature a mobile quarterback have a numerical advantage against one-gap defenses. You can only stack so many defenders in the box before it becomes a kamikaze mission, and the offense is able to add an extra man in the box (in theory) by optioning the quarterback.

To solve this, Mason employs a two-gap system that provides an extra gap. Rather than being a one-gap and go side, defensive lineman hold the point of attack, read the defense and react to the ball.

Spread offenses make a living by pounding the ball inside, before collapsing the interior and overwhelming the outside of a defense, for instance, a lineman crashing inside on an option play.

Mason’s two-gap system looks to maintain its structural integrity by having its edge defenders sit and react. This puts pressure on interior lineman to be disciplined, as well as the inside linebackers to consistently make good decisions.

Linebacker depth

The system puts a high degree of stress on the play of the inside linebackers. As the edge-defenders funnel running backs inside in an attempt to limit explosive plays to the outside, linebackers must make the right decision when dropping to the line of scrimmage (LOS), or flowing to the ball if it goes to the outside.

In Zach Cunningham, Vanderbilt has one of the best read-and-react defenders in the country. Individual talent always trumps schemes, and the growth of Cunningham inside has allowed Mason’s two-gap system to work. His talent level makes everyone’s job easier, and thus the scheme better.

But Mason does more than just rely on his linebackers to make the correct decision.

When facing spread looks he shuffles them back a couple of extra yards. Instead of sitting at the typical depth of 4 or 5 yards off the LOS, they move to a depth of 6 or 7 yards.

The tactic can appear somewhat counterintuitive. It gives power-spread teams a couple more yards with which to run the ball into. Mason is willing to absorb that in order to stop explosive plays. Giving his linebackers extra depth allows them a split-second longer to read before reacting, and forces the offense to make “option” decisions quicker.

Mason is comfortable giving up an extra yard on a per-play basis, if it means stopping the explosive boundary plays from offenses such as Auburn, Texas A&M and Oregon.

Two down-lineman look

In the modern-age of mostly spread offenses — heck, even Alabama now runs a form of the power-spread — defenses are less and less in their “base” defense and spend almost the entire game in smaller sub-packages: nickel, dime, etc. We are now prone to seeing more 3-3-5 and 4-2-5 looks than 4-3 or 3-4 looks.

The reality is that the offenses are now using all five eligible players on each offensive snap better than ever, and they’re doing so with explosive players at each position.

Other X’s and O’s Features

To counter this, defenses have needed to get smaller, and get as much speed on the field as possible. Gone are the days of downhill thumpers at the inside linebacker spot. If you can’t play in space and move your hips, you’re gone.

Mason has taken two approaches to get more speed on the field.

The first is showing more two down-lineman fronts, with four standup linebackers, rather than three in obvious passing situations.

It makes them much lighter against the run, but gets as much speed on the field as possible to cover all of the open space.

Moreover, playing with four linebackers and just two lineman allows the defense to grab back some of the decision-making impetus. They’re still likely to rush three or four, and with a number of hybrid players (more on that in a moment), but it can become a guessing game for the offensive line and quarterback to try and figure out where the rushing linebackers are coming from.

The “Star” Linebacker

Sometimes referred to as the “Joker,” the “Star” linebacker is a linebacker/defensive back hybrid.

The “Star” is what at one time would be called a “tweener,” a player somewhere between a fluid-moving free safety and an outside linebacker. The Star is there to protect against pre-snap motions/shifts, as well as add even more athleticism to defend against spread looks.

Many defenses have been using a “Leo” linebacker for years. A hybrid defensive end/outside linebacker who they’re comfortable with dropping into space if it’s required. The “Star” focuses more on being versatile on the back-end than it does upfront.

Obviously those kinds of players are tough to find. They must be mobile, have quality change of direction skills, outstanding diagnose and attack instincts, and be comfortable in space.

That type of player is not easy to find, but in Oren Burks the Commodores have a very good player, with a tweener skill-set, and the ability to make plays against the run, or drop into coverage. He started at that spot for Vandy last year, and returns as a starter for the 2016 season.

Shorten rotations

At schools like Vanderbilt, shortening your rotations is often forced. The drop in caliber between the first and second string at multiple positions is precipitous, thus making consistently rotating out players damn near-impossible, despite rising snap-counts.

Sides like the 2015 Alabama team have such overwhelming depth and talent that they are able to consistently rotate their defensive front, keeping everyone fresh, and at their peak level of performance when they enter the game.

For Mason, he shortens his rotation by design.

In his first year at Vanderbilt he told FoxSports: “We just need to keep our best 11 on the field as often as we can.” With such a taxing mental scheme, and specific requirements needed at all positions, Mason limits his snap-to-snap rotation and concentrates on building a flexible 11 that can shift to defend most pre-snap looks.

Furthermore, with offenses going at such break-neck speeds, they’re banking on defenses struggling to rotate, have breakdowns in communication, and becoming unnecessarily vanilla. By keeping the same personnel on the field, Mason is able to better prepare for what his defense may see, and there are fewer opportunities for communication breakdowns as players sub in and out.

Mason relies on his first string, what he calls the “goons” for 60 snaps per game, and his second string, the “goblins,” for a couple of series.

***

As Vanderbilt heads into 2016, it is set to see no shortage of option and spread attacks, playing at Georgia Tech, Western Kentucky and Auburn, while playing host to Ole Miss and Tennessee.

The Commodores certainly fall short of many of those teams in terms of overall talent, offensively they’re flat-out awful, but on defense they will continue to throw in new wrinkles and innovate.

The SEC has already begun to learn from what Mason did at Stanford and is doing now with Vanderbilt; showing more two-gap schemes on early downs, shortening rotations, and increasing the depth of linebackers on possible option plays.

Mason may not generate the kind of wins he is hoping for at Vandy, that will come down to recruiting and improving on offense and special-teams. But he has already put a mark on the conference defensively, both before his arrival and during his time in it.

Whether he is ultimately a successful head coach is yet to be seen, but his status as a great defensive mind is earned and coaches from all leagues, including the SEC, will continue to study Vanderbilt’s tape to see what new strategies Mason sprinkles in.

Oliver Connolly is the editor-in-chief of TheReadOptional.com and a football columnist. He’s a former recruiting advisor for Western Michigan University, a contributor to SI Draft research, a college football writer for Saturday Down South, and a member of the Pro Football Writers of America.