The Ultimate National Championship Preview: Alabama vs. The Best Imitation of Itself

By Matt Hinton

Published:

It’s January, which in college football means we’re well past the point in the season at which there’s anything left to say that hasn’t already been said, repeatedly, and then said again just for good measure. The hay is in the barn, as the old coaches used to say.

And when it comes to breaking down two of the most high-profile teams in the most high-profile conference in the wake of their high-profile victories on the most high-profile day on the sport’s annual calendar, then the hay has already been in there a good long while, long enough that originality is kinda beside the point. The National Championship Game is the National Championship Game. What could possibly be left to say about the 2017 editions of Alabama and Georgia, except let’s get it on?

As the kickoff in Atlanta looms, though, it is worth remembering how large a potential Bama-UGA climax loomed over so much of the regular season, sitting off on the horizon, biding its time. It was obvious right away that the teams were mirror images of one another, Georgia’s rapid ascent under Kirby Smart so eerily similar to the one he’d helped forge in Tuscaloosa a decade earlier that the narrative almost felt scripted in advance. Clearly these were the two best teams, certainly in the SEC, if not the nation.

By November the showdown seemed so inevitable that it was almost as if we’d already seen a trailer promising the final, climactic battle, and everything in between just felt like filler.

At the time, of course, the assumption was that the winner-take-all showdown would come in the SEC Championship Game, not in the Big One itself, and the fact that it didn’t quite unfold that way — that Auburn intervened, knocking both the Bulldogs and Crimson Tide off their pedestals in a matter of weeks, and very nearly knocking Bama out of the championship conversation altogether — doesn’t diminish the fact that, ultimately, the matchup for all the Tostitos in Atlanta is the one we really wanted to begin with: Upstart vs. Empire, Protégé vs. Mentor, Original Flavor vs. New and (maybe) Improved.

Athletically, both sides will arrive boasting one of the most monolithically talented rosters in the nation, featuring more 5-star prospects from top to bottom (18 on Bama’s sideline, 11 on Georgia’s, according to 247Sports’ composite rating) than any other FBS teams. Philosophically, both are built on a foundation of controlling the line of scrimmage on both sides of the ball, the better to wear opponents down while protecting their precocious young quarterbacks. Statistically, they’ve spent all season neck-and-neck in almost every category that matters.

The existence of two elite outfits with so much shared DNA almost demands that they collide on this type of stage. Now that the climax has finally arrived, the twist ending is that we were right all along.

So, with all that said, finally: Let’s get it on.

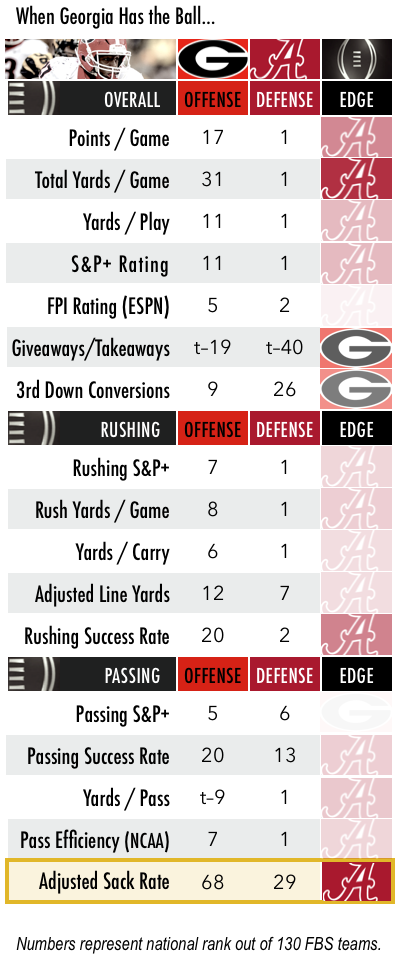

WHEN GEORGIA HAS THE BALL …

Thirty-two. If you don’t know the number by now, you will by the end of Monday night: That’s how long it’s been, 32 years, since the last time a team won a national championship with a true freshman quarterback taking the majority of its snaps, and the specific circumstances under which Oklahoma’s Jamelle Holieway set the standard in 1985 aren’t exactly applicable to Jake Fromm in 2017.

(Holieway, a triple-option type, took over for injured starter Troy Aikman early in the season and completed a grand total of 24 passes on the year.)

Jalen Hurts came as close as it’s possible to come last year without actually finishing the job, and might have been the first since Holieway to even make such a thing seem plausible; in the intervening three decades no other rookie QB even made it within spitting distance. As a rule, freshman starters don’t bring home the hardware.

But Fromm has a lot going for him in his ongoing defiance of said rule, most of which — as with Holieway and Hurts before him — has less to do with his own performance than with his surroundings. In Fromm’s case, they’re ideal: His top three backs, Nick Chubb, Sony Michel and D’Andre Swift, have accounted for more than half of Georgia’s total offense with their rushing output alone, leaving Fromm to shoulder the smallest burden relative to his team’s overall production (a little over 40 percent) of any full-time SEC starter.

The Bulldogs’ overwhelming success on the ground has also made Fromm’s life easier when he does put the ball in the air, softening up defenses for big plays via play-action passes. And his receivers have made a habit of hauling in some truly spectacular catches that sometimes, frankly, have no business being caught.

Javon Wims shows off some serious footwork.

After review, this is a @FootballUGA touchdown. pic.twitter.com/gyNUOsaCkB— SEConCBS (@SEConCBS) November 4, 2017

The run-first model has faltered exactly once, in Georgia’s 40-17 loss at Auburn on Nov. 11, and without the ground game to serve as scaffolding Fromm seemed to crumble right along with it. At the time, that just seemed like part of the bargain of starting a 19-year-old who’d never been forced to play from behind in a hostile environment.

From that point on, though, all signs are that Fromm really is the steady, poised-beyond-his-years phenom the early returns suggested. In the regular-season finale, he was nearly perfect against Georgia Tech, bombing the Yellow Jackets for 224 yards and a pair of long touchdowns on just 16 attempts. In the rematch against Auburn he was efficient and composed, finishing 16-of-22 for 183 yards, 2 TDs and zero picks in a resounding response in the SEC title game. In the Rose Bowl, he more than held his own against Oklahoma’s Baker Mayfield, quietly posting a better efficiency rating in the biggest game of the season than the most efficient passer in FBS history. (Fromm finished with a 152.6 rating on 29 attempts, compared to Mayfield’s 147.7 — the latter coming in more than 50 points below his record-breaking season average.) Beyond the stat line, Georgia’s final drive of regulation was the stuff of budding legend: Trailing 45-38 with 3:15 to play, Fromm proceeded to hit 3-of-4 attempts on the Bulldogs’ last-gasp possession, accounting for 48 of the team’s 59 yards en route to the game-tying touchdown that forced overtime. After that performance, in his 13th career start, it almost seems unfair to continue to think of him as a freshman.

From that point on, though, all signs are that Fromm really is the steady, poised-beyond-his-years phenom the early returns suggested. In the regular-season finale, he was nearly perfect against Georgia Tech, bombing the Yellow Jackets for 224 yards and a pair of long touchdowns on just 16 attempts. In the rematch against Auburn he was efficient and composed, finishing 16-of-22 for 183 yards, 2 TDs and zero picks in a resounding response in the SEC title game. In the Rose Bowl, he more than held his own against Oklahoma’s Baker Mayfield, quietly posting a better efficiency rating in the biggest game of the season than the most efficient passer in FBS history. (Fromm finished with a 152.6 rating on 29 attempts, compared to Mayfield’s 147.7 — the latter coming in more than 50 points below his record-breaking season average.) Beyond the stat line, Georgia’s final drive of regulation was the stuff of budding legend: Trailing 45-38 with 3:15 to play, Fromm proceeded to hit 3-of-4 attempts on the Bulldogs’ last-gasp possession, accounting for 48 of the team’s 59 yards en route to the game-tying touchdown that forced overtime. After that performance, in his 13th career start, it almost seems unfair to continue to think of him as a freshman.

So regardless of his age, we’re not taking about a lamb to the slaughter here on a big stage. But nor does Alabama’s defense limit its slaughtering to lambs, as Clemson just learned the hard way in the Sugar Bowl — the Tigers finished with Dabo-era lows for total yards (188) and yards per play (2.7), didn’t manage a single gain longer than 20 yards, and failed to reach the end zone for just the second time in Swinney’s decade-long tenure.

After a couple of (relatively) shaky November outings against Mississippi State and Auburn, the message was abundantly clear: Bama’s defense remains Bama’s defense. Coming out of the semifinal the Crimson Tide rank No. 1 nationally in total defense, scoring defense, rushing defense, pass efficiency defense, yards per play allowed, yards per carry allowed, yards per pass allowed and Defensive S&P+, just for starters. To suggest that this looks like the dominant unit in college football right now would be a vast understatement.

As ever, that distinction begins along the front line, where Alabama’s rotation of Da’Shawn Hand, Da’Ron Payne, Raekwon Davis and Isaiah Buggs combines all of the next-level potential of last year’s celebrated D-line with (so far) only a fraction of the name recognition outside of the Tide fan base.

That won’t be the case by the start of next season, when Davis and Buggs will be touted as preseason All-Americans — Hand is a a senior, and Payne is almost certainly off to the NFL a year early — and if Georgia’s ground game goes the way of Clemson’s then it might not be the case by the start of the fourth quarter on Monday. It doesn’t take a Bama diehard to recognize a dominant effort from a fully Sabanized defensive front, a show we’ve seen many times before on this stage and others. An inability to get anything going on the ground leads directly to vulnerability against the pass rush, which leads, eventually, to utter catastrophe.

On the other hand, UGA’s rushing attack is likely the best Alabama has seen in its own right, and more than capable of mounting a semblance of a ground game on the order of LSU’s rushing output against the Crimson Tide (209 yards on 5.8 per carry, excluding sacks), or Mississippi State’s (182 on 3.8 per carry), or Auburn’s (172 on 3.6). In that case, then it’s much easier to imagine the Bulldogs controlling the clock to the same extent as those offenses, each of which racked up at least an 8-minute advantage in time of possession.

There’s not much hope of Fromm or his offensive line withstanding the onslaught that follows when Alabama no longer respects the run, much less thriving. As long as play-action remains viable, though, Fromm may be the most capable passer Bama has faced outside of Auburn’s Jarrett Stidham. And if there’s any offense in America capable of slugging it out with the Tide for the better part of four quarters, it’s the one built the most deliberately in their image.

Key Matchup: Georgia OL Ben Cleveland vs. Alabama DL Raekwon Davis: Bama’s entire front qualifies as a mismatch, pretty much regardless of who’s attempting to block them. But none presented more problems to opposing linemen this year than Davis, a 6-7, 306-pound sophomore who’s built like a basketball player and hits like a truck. Davis led the team in sacks and tackles for losses, most of them coming at the expense of guards overwhelmed by his speed, and earned a first-team All-SEC nod for his efforts despite coming off the bench in seven of the Tide’s 13 games.

1/1/18 (Sugar Bowl): Alabama DT Raekwon Davis sacks Clemson QB Kelly Bryant pic.twitter.com/bU8v6Woqpq

— College Football Clips (@CFB_Clips) January 5, 2018

Cleveland, a redshirt freshman, has no such accolades: He only moved into the starting lineup in mid-November, replacing Solomon Kindley at right guard after the regular-season flop at Auburn. He’s held down the job in all four games since, all of them dominant rushing performances in which he’s consistently graded out as one of the team’s top blockers; according to Pro Football Focus, he was Georgia’s highest-graded player in the Rose Bowl, period, on either side of the ball. Oklahoma’s D-line is a considerable step down from Alabama’s, so whether that will carry over against Alabama — or whether it will be good enough to contain Davis, Payne, et al., even if it does — is an open question. But it’s not hard to guess how Cleveland’s night will go if it doesn’t.

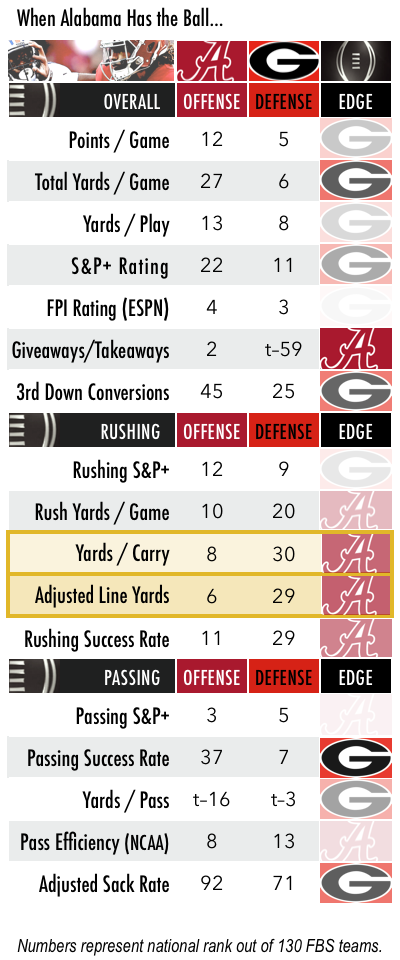

WHEN ALABAMA HAS THE BALL …

As reassuring as it was defensively, the semifinal romp over Clemson didn’t resolve any of the lingering questions surrounding the offense: Bama finished with its worst output in terms of both total yards (261) and yards per play (4.0) since the 2013 opener against Virginia Tech — a span of nearly five full seasons — and managed a single gain of 20 yards or more. (That came in the second quarter, when freshman RB Najee Harris picked up 22 on a short flare pass out of the backfield, his only touch of the game; the drive subsequently ended with a punt, anyway.) The feature backs, Damien Harris and Bo Scarbrough, logged a season-high for carries (31) but averaged just 3.2 yards on those attempts with a long gain of 11. Both of the Crimson Tide’s touchdown drives began in Clemson territory.

To be fair, in the context of a single game against an elite opponent it’s easy to shrug off that effort as a mere footnote; the Tigers’ D lived up to the hype as one of the best in the nation in its own right, and Alabama obviously spent much of the second half throttling down with a secure lead. Frankly, as little threat as Clemson’s offense posed to reach the end zone itself there was never much incentive to push the gas pedal in the first place.

Still, taken as an extension of the regular season there’s no way to square that kind of complacency with the broader, mostly discouraging trend. November was a sobering month for the offense, one that began with an uninspiring performance at LSU and ended with an outright flop in the Iron Bowl. Even going as far back as the season-opening win over Florida State, where Alabama managed just 269 total yards and two offensive touchdowns — one of them coming on an 11-yard “drive” following a late FSU fumble — the pattern holds: Against blue-chip defenses that can roughly match their talent level the Crimson Tide have consistently tended to look average, or worse, to a far greater extent than they have in years.

I highlighted that 5-year window from 2012-16 because those were the years the offense featured either a) AJ McCarron, a Heisman runner-up and future draft pick, as its starting quarterback, in 2012-13, or b) Lane Kiffin as its offensive coordinator, from 2014-16. This year’s attack features neither, although it did return the vast majority of its production from last year’s championship run, and the results speak for themselves — from a thousand-foot view, the decline against respectable competition has been palpable, in terms of both tempo and overall production. The Sugar Bowl was only the most recent and most obvious example that the 2017 edition has largely reverted to the original factory settings.

And to some extent, maybe that was the idea all along: Although strictly speaking Alabama is still a “spread” offense, certainly Saban didn’t hire Brian Daboll, a longtime NFL assistant with no play-calling experience at the college level, to hone the finer points of the read option. But as the season has worn on it’s become increasingly clear just how constrained the offense is by the limits of Jalen Hurts’ arm. In certain respects, Hurts is a rock, a resilient, unflappable leader with a 25-2 record as a starter, a wealth of big-game experience, and an enviable aversion to mistakes. (In 246 attempts this season he’s thrown a single interception, good for the nation’s best INT rate by a mile.) In all of those ways he’s a better quarterback as a sophomore than he was last year as a true freshman, while also sustaining his role as a productive, every-down threat in the ground game. As a passer, though, he’s not about to scare any opposing secondaries on a big stage, and at this point it’s a fair question whether he ever will.

And to some extent, maybe that was the idea all along: Although strictly speaking Alabama is still a “spread” offense, certainly Saban didn’t hire Brian Daboll, a longtime NFL assistant with no play-calling experience at the college level, to hone the finer points of the read option. But as the season has worn on it’s become increasingly clear just how constrained the offense is by the limits of Jalen Hurts’ arm. In certain respects, Hurts is a rock, a resilient, unflappable leader with a 25-2 record as a starter, a wealth of big-game experience, and an enviable aversion to mistakes. (In 246 attempts this season he’s thrown a single interception, good for the nation’s best INT rate by a mile.) In all of those ways he’s a better quarterback as a sophomore than he was last year as a true freshman, while also sustaining his role as a productive, every-down threat in the ground game. As a passer, though, he’s not about to scare any opposing secondaries on a big stage, and at this point it’s a fair question whether he ever will.

That’s not to suggest Bama’s downfield passing game is completely doomed; Hurts completed 21 passes this season for 25 yards or more, half of them to Calvin Ridley alone. The last time the Crimson Tide played in Atlanta, in the opening-day win over FSU, Hurts and Ridley hooked up on a 53-yard TD pass that stands as arguably the most impressive throw of Hurts’ career. Relatively speaking, though, the big plays were few and far between, and many of them came as the result of yards after catch rather than Hurts’ ability to stretch to the field. More often, the Crimson Tide’s passing game has served as an extension of the running game, continuing to rely heavily on the same menu of horizontal screens and swing passes that propped up Hurts’ numbers as a freshman.

Of the 24 attempts that left his hand against Clemson, only two traveled more than 15 yards downfield, both of which — a flea flicker in the first half, a bootleg pass in the second — landed short of open receivers despite minimal pressure on Hurts as he released the ball. More than two-thirds of his passing yards against the Tigers (82 of 120) came after the catch. Against Auburn, he was 2-of-7 on throws more than 15 yards downfield, with roughly half of his overall output coming after the catch.

Against LSU, arguably Hurts’ most aggressive game as a passer, he was 3-of-4 on attempts in the 15-20-yard range but just 2-of-6 beyond. Whatever marginal growth he might have demonstrated from Year 1 to Year 2 on intermediate throws, on true deep balls there’s been little progress. In that sense it seems the Hurts we’ve seen the past two years is the guy he’s going to be for the rest of his career.

Exactly how much any of that will matter against Georgia, of course, depends on how effectively the Crimson Tide are able to establish the run, and Hurts may be the most vital component of the equation.

On paper, the Bulldogs’ secondary is as unforgiving as any Bama has seen this season, fresh from holding Baker Mayfield to his most ordinary stat line of the season. (Restricting Mayfield to the realm of mere mortals statistically is the equivalent of shutting most quarterbacks down completely.) \

The other quarterbacks who have had some success challenging UGA deep — namely, Missouri’s Drew Lock and Auburn’s Jarrett Stidham — have NFL ambitions and the arm strength to back it up. But Oklahoma had surprising success in the Rose Bowl running right at Georgia, springing oversized tailback Rodney Anderson for 201 yards rushing on nearly 8 per carry, almost all of it coming on the kind of straightforward inside zone, outside zone, and counter plays that can be found in virtually every college playbook.

Trey Sermonpic.twitter.com/ZSXYUbcnbv

— LeOusmane DeMessi Pats 13-3 Barça 14-3-0 (@ChrisCreacy) January 2, 2018

Altogether, the Sooners’ output on the ground was virtually identical to the 237-yard thumping Auburn put on the Bulldogs in November, the only real difference being that Oklahoma suffered more negative yardage on sacks.

Broadly speaking, if Alabama’s offense has a likely advantage on Monday night, it’s in the trenches, and it’s hard to imagine a blueprint for the Tide that doesn’t begin and end behind a veteran O-line that averages more than 310 pounds per man: Establish the run, keep Hurts out of obvious passing situations, and dictate when he takes his shots downfield rather than have it dictated to him by the down and distance (or, worse, the scoreboard).

That’s proven to be a much tougher sledding down the stretch than it was over the first half of the season, or at any point last year, when the same set of backs ran at will on just about everybody. But that’s what this offense is ostensibly built to do, and as long as Hurts, Harris, and Scarbrough are sharing the same backfield there’s still no other lineup in America better equipped to do it when it really counts.

Key Matchup: Alabama TE/H-back Hale Hentges vs. Georgia LB Roquan Smith: Oklahoma’s overtime play-calling against Georgia was highly second-guessable in a couple ways. One, the Sooners effectively took the ball out of the hands of their Heisman-winning quarterback, running or throwing behind the line of scrimmage on eight of nine plays in the OT sessions. And two, despite their sustained success between the tackles in regulation, almost all of those plays attempted to attack the perimeter, which as SEC fans could have predicted did not go over well vs. the Bulldogs’ heat-seeking, All-American middle linebacker.

1/1/18 (Rose Bowl): Georgia LB Roquan Smith pursues for tackle vs. Oklahoma’s Jordan Smallwood. pic.twitter.com/veBWgAgNNu

— College Football Clips (@CFB_Clips) January 5, 2018

Smith finished with a team-high 11 tackles, further cementing his reputation as the game’s most ferocious sideline-to-sideline enforcer despite his 6-foot-nothing, 225-pound frame. For much of the game, though — especially in the first half — Smith was frequently lost in the wash against the run, struggling to shed vastly larger offensive linemen when Oklahoma opted to pound it straight ahead. For all of the flares and screens Alabama deploys to keep defenses honest, pounding it straight ahead remains the Crimson Tide’s bread and butter, too, and for as little attention as Hentges and Irv Smith Jr. receive in the H-back role they remain fundamental to the Tide’s success as lead blockers.

In fact, although they’re technically listed as tight ends, the way the role has evolved this season it might be more accurate to describe the H-Backs as Bama’s de facto fullbacks: Between them, Hentges and Smith’s combined receiving numbers aren’t even halfway to O.J. Howard’s totals last year in the same position. But they do have Howard’s next-level size (both check in in the 6-4, 250-pound range) and how they fare in their efforts to outmuscle Smith at the point of attack will go a long way toward determining the course of Alabama’s play-calling as the night unfolds.

SPECIAL TEAMS, INJURES AND OTHER VAGARIES

The worst possible result from an entertainment standpoint would be another bite-and-hold punt fest like the one Alabama and LSU staged in the 2011 title game — you know the rest of the country is dreading this above all else, and ESPN is, too — but if punting’s your thing, this game will feature two of the best in Alabama’s JK Scott and Georgia’s Cameron Nizialek: Of their combined 103 punts this season, only 16 have been returned and only eight have resulted in touchbacks.

The majority of the rest were either fair caught (49.5 percent) or downed inside the opposing 20-yard line (45.6 percent). There’s a good chance we’ll see a lot of both Scott and Nizialek, which should keep field position aficionados on the edge of their seats — as a testament to their efficiency, Alabama’s defense ranks second nationally in average starting field position, Georgia’s twelfth.

That will limit opportunities in the return game, especially for Georgia’s Mecole Hardman Jr., a former 5-star recruit who posted the SEC’s best average on both kickoff and punt returns but didn’t score a touchdown in either capacity. (Hardman did score four TDs on offense, as both a rusher and receiver, compounding the frustration that he’s yet to house one as a return man.)

Alabama cycled through multiple options on punt returns, in part because none of them could seem to hold on to the ball: Trevon Diggs, Xavian Marks and Henry Ruggs III all fumbled multiple times over the first two-thirds of the season before finally settling down in November. With the athletes on hand a lightning strike in the return game is always looming on the horizon, but a crippling miscue is just as likely.

The field goal kickers, Georgia’s Rodrigo Blankenship and Alabama’s Andy Pappanastos, are both fine on short-to-medium kicks, connecting on a combined 25-of-26 from 39 yards and in; from longer range things get dicey. (To his credit, Blankenship did bury a career-long 55-yarder in the Rose Bowl, crucial points for the Bulldogs just before a halftime; that was his first attempt from beyond 50 yards this season.)

On that note, keep in mind that although neither side has allowed a blocked field goal or punt this year, both sides have multiple blocks themselves, including Georgia’s decisive swat against Oklahoma in double overtime.

On the injury front, the story is still dominated by Alabama’s beleaguered linebacking corps, which just added Anfernee Jennings to a casualty list that already included one full-time starter, Shaun Dion Hamilton, as well as top reserve Dylan Moses.

But signing the No. 1 recruiting class year after year has its advantages, and ludicrous depth is one of them. Mack Wilson looked great against Clemson in his first game back from a lingering foot injury, which also happened to be his first career start in Hamilton’s usual place at Mike. Ditto sophomore safety Deionte Thompson, whose first start in place of injured starter Hootie Jones went off without a hitch. If Christian Miller and/or Terrell Lewis — both of whom returned against Clemson after spending most of the regular season on the shelf themselves — can make the same kind of seamless transition in Jennings’ usual spot, the drop-off should be negligible, if there is one at all. Each of the new starters arrived in Tuscaloosa as a top-50 overall prospect in his respective recruiting class.

BOTTOM LINE

Alabama doesn’t do second place, a point driven home earlier this week by its completely insane strength coach, Scott Cochran, when he annihilated the runner-up trophy from last year’s championship loss to Clemson in a fit of motivational pique. That sums up the Crimson Tide’s mindset in this game: Although they’re favored to win (Alabama is always, always favored to win) for this team there is nothing like the wave of inevitability that carried them onto this stage the past two years. Last year they left the field as runners-up; this year, they’re back as runners-up in their own division, in their own state, having absorbed a solid month’s worth of skepticism over whether they even belonged in the Playoff conversation at all.

The big-picture momentum is clearly with Georgia, the reigning SEC champ regardless of what happens on Monday night, and the first program in years that seems poised to offer a legitimate, sustained threat to Bama’s supremacy as conference overlord.

Kirby Smart has built his own version of the Death Star, one that by all appearances is just as big and bad as the original, and which may have the potential to surpass it. Meanwhile, a team from something called the American Athletic Conference has already declared itself national champion, also regardless of what happens on Monday night. The moment is rife with disrespect.

But on the same note, while the memories of past Bama juggernauts running roughshod over their last remaining obstacle to the title are still fresh, this particular team has yet to earn the same benefit of the doubt. The Tide destroyed bad teams over the first half of the schedule, but looked underwhelming against good ones; the defense has established its place in the lineage of great Bama outfits under Nick Saban, but the offense has not — at least, not against above-average competition. Every team has its own internal monologue, something that it needs to prove to itself. This is the first Alabama team in years that has any reason to feel like it still has something to prove to the rest of the world. So it’s fitting, as Saban has always preached, that the only way to do it is by essentially beating a fully operational version of itself.

6 PREDICTIONS

• A special teams gaffe plays a prominent role.

• Both veteran tailback tandems — Chubb/Michel and Harris/Scarbrough — log season highs for combined carries in their final game together, though both also wind up averaging less than five yards a pop.

• Jake Fromm completes upwards of 50 percent of his passes, but for less than six yards per attempt, and finishes with multiple turnovers for the first time this season.

• Jalen Hurts accounts for more than 250 yards of total offense, well above his season average, the majority of it coming via Calvin Ridley.

• Georgia’s offense goes at least one full quarter without running a play in Crimson Tide territory.

• Alabama wins, 24–19

Matt Hinton, author of 'Monday Down South' and our resident QB guru, has previously written for Dr. Saturday, CBS and Grantland.