SEC 360: Former Alabama QB Brodie Croyle impacting souls at Big Oak Ranch

Editor’s note: Welcome to SEC 360, where each week Al Blanton takes a big-picture view of SEC football and its impact.

Brodie Croyle sat on his bed in his suburban Kansas City house, studying his playbook. As a quarterback for the Kansas City Chiefs, there was much work to be done.

The former Alabama signal-caller had a goal of becoming the starting quarterback in K.C., and to that end he was laser-focused. His days bookended with blackness, he would arrive at the practice facility at dark and leave at dark. Preseason was a time to be completely eaten up by football, and without question, Croyle was consumed by it.

But that night as he crawled into bed, it’s doubtful he believed he would have an epiphany that would smack him in the face like a rushing linebacker and materially alter the trajectory of his life. His needle, as it turns out, was moving away from football, the thing that had been elbowing its way to Space Number One in his life since he was 11 years old.

As he was studying the Xs and Os outlined in the Chiefs’ playbook, the coverages, the checks, and all the moving parts, he glanced at his wife, Kelli, who was studying another playbook.

“My wife is sitting there and she’s reading her Bible,” Croyle recalls. “Little did I know for an entire year, she’d been doing it every night.”

Thunderstruck by his wife’s devotion, Croyle’s idolatry was somehow blatant now. Coming face-to-face with his sin, he realized he hadn’t been the husband he needed to be because this idol had taken top billing in his life. He hadn’t been the spiritual leader he needed to be because for years he had been like a mechanical rabbit chasing a dangling carrot. Football was the thing he’d been relentlessly pursuing, worshipping.

Finally, he closed his playbook, leaned over to her, and in his distinct northeast Alabamian/Appalachian twang made her a promise: “Baby, I’m sorry. I’ve failed you. I know the man I am supposed to be and I just haven’t been it. I’m not going to be perfect. But starting now, I have to begin the journey of being the man you thought you were marrying.”

Croyle had been on a much different journey. When he was just a kid, he walked into his parents’ bedroom and told them brazenly, “I’m going to play in the NFL.” No matter that he had never played one down of football his life. But instead of discouraging their son or laughing at his lofty goals, his parents told him, “Shoot for the moon. Heck, worst-case scenario, you’ll end up in the stars!”

“And I’m ashamed to say that day, football became my god,” Croyle said.

Still, he did the church thing. He’d first gotten saved at age 6, baptized at 9. And even though football had reared its massive head by age 11, by 15, he was rededicating his life to the Lord.

“I did all the things a young Southern boy was supposed to do,” Croyle admits.

Distractions, they did come. As a football hero at Westbrook Christian in Rainbow City, Alabama, he became mesmerized with the attention that it brought. Wins, atta-boys, and passing records became the lighter fluid for a mania that raged, while all the while his faith slowly climbed into the back seat of his life. “It’s not that God went away, it’s that football became top on my list,” Croyle said. “As I got older, and as I got more successful in that football thing, the further and further God went down my list.”

Because of Croyle, a deluge of recruiting attention fell on Rainbow City. Coaches like LSU’s Nick Saban, Florida State’s Bobby Bowden, and others were hot on the trail of the 5-star stud with the rifle arm. As Croyle was making a decision between a near-Rolodex of elite programs, something Bowden said in a home visit helped Croyle to choose the Crimson Tide over the Seminoles. Yes, you read that right.

Croyle says that when the two men were having a conversation in the living room after a spaghetti supper, he said to Bowden, “Coach I’m really leaning toward going to Florida State, and I want to know if you are going to be there.” (A bit of context: The year was 2000, and Bobby Bowden was one year removed from a national championship over Michael Vick and the Virginia Tech Hokies. He was in his early 70s and the scuttlebutt was that his retirement might be imminent.)

According to Croyle, Bowden replied with expected profundity. “He said, ‘Son, you don’t go to a University because of head coaches. Head coaches come and go. You go to universities that you want to tie your name to,’” Croyle remembers.

“He said that as a recruiting pitch to Florida State, because at that point they were the Mecca. You want to tie your name to that.”

But when he spoke those words, he spoke to a boy who grew up with a dad that played at Alabama, to a teenage kid whose fantasies danced with images of playing quarterback for the mighty Crimson Tide. Through that conversation with Bowden, through those words, Croyle realized he wanted to go where his heart was leading him. There was simply too much Alabama pumping through his blood. It was Alabama, not Florida State, that Brodie wanted to tie his name to, because the roots were deep.

John Croyle, Brodie’s father, played for the legendary “Bear” Bryant in the 1970s but had a vision to start a ranch for hurting boys. Shortly after his playing career was over, in 1974, he founded Big Oak Ranch just outside of Gadsden. Throughout the years, John welcomed hundreds of children who were abused, battered, abandoned and otherwise mistreated into his loving embrace, but also used his platform to share the gospel to various groups around the state. John had such success and his ministry so blessed that in 1988, he opened the Ranch’s twin: a girls’ ranch in Springville, Alabama.

So by the time Brodie reached high school, his father was a well known and well respected Alabamian. Admittedly, part of Brodie’s internal struggle was that he wanted to create his own identity, separate from his father.

That identity, he surmised, involved the building of a great football player who would be praised by men.

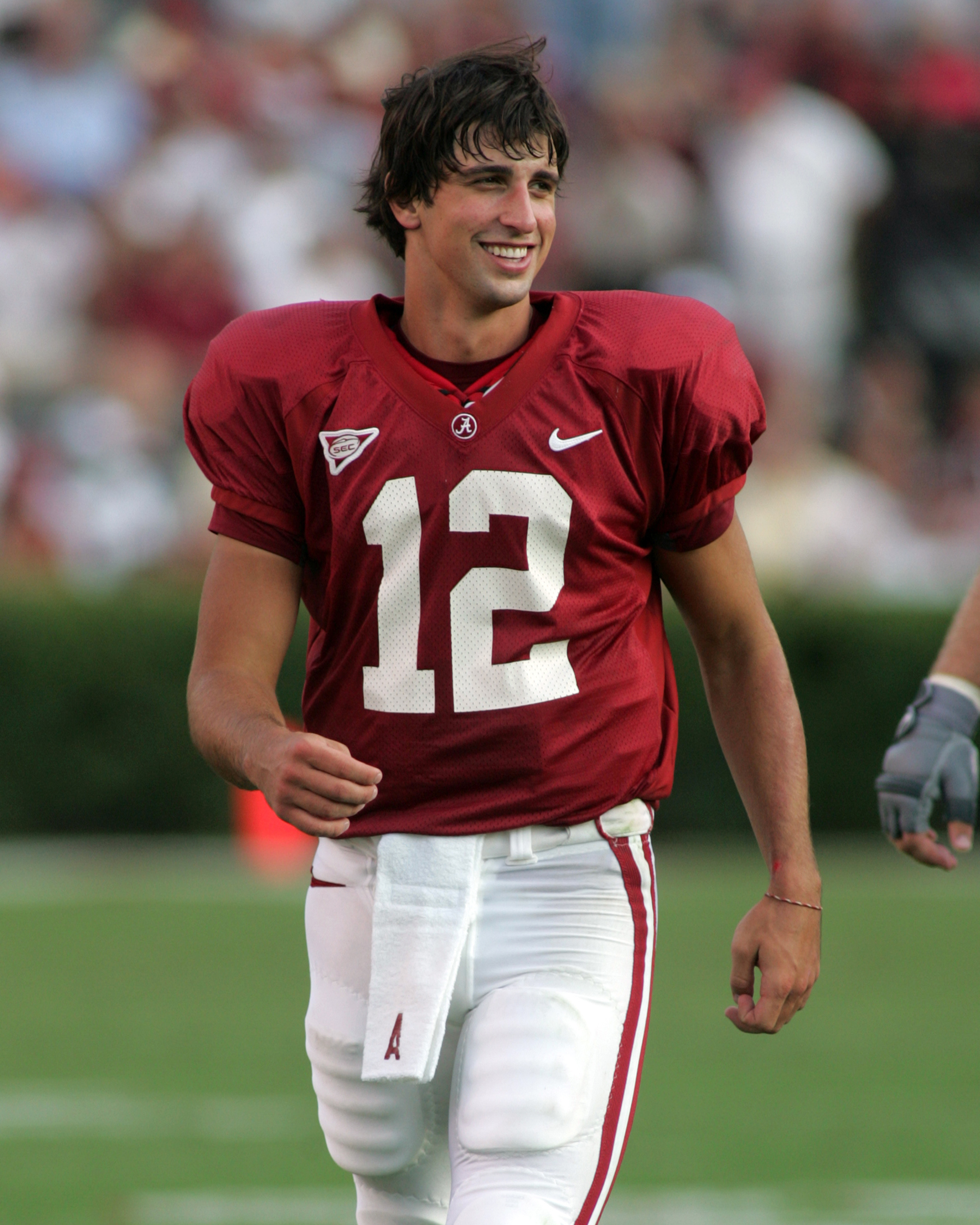

At Alabama: The next Great One

Photo courtesy of Brodie Croyle

College, for Brodie Croyle, became an opportunity to let his hair out, both literally and figuratively. He was already famous before he stepped onto Alabama’s campus — his oak-strong lineage and gridiron skills the primary catalysts for his notoriety — but in Crimson Country the hype surrounding his arrival reached feverish proportions. To make matters worse, fans learned that he would wear No. 12, conjuring thoughts of a second coming of another Tide quarterback named Namath. But Brodie says that number chose him, not the other way around. “When I was getting recruited, literally from my 10th grade on, every time (Alabama) would write me a letter, they would put No. 12 on the letterhead,” Croyle said. “Stabler was No. 12, Namath was No. 12, and that’s what they were wanting me to envision.”

Alabama hadn’t had a truly great quarterback in years, and fans hoped — believed — Croyle was “The One.” Croyle says he was cognizant of the pressure but was able to shelf it in the back of his mind, in part because “I had such higher expectations than everybody else did.”

In retrospect, it was a volatile time in the program’s history. Mike Dubose had recently made his exodus and Alabama hired Dennis Franchione, a wild card out of Texas and not the most popular choice among fans, as his replacement. Regardless, Croyle was a big pickup for the Tide at a time when the recruiting truck bed was light.

With looming probation and a carousel of coaching changes, Croyle’s years at Alabama were saga-filled. In un-Alabama fashion, the Crimson Tide endured three head coaches, a 4-win season, losses to the likes of Northern Illinois and Hawaii, and gobs of turmoil. And despite the varying transgressions of Franchione (bolting for Texas A&M), Mike Price (strip club incident) and Mike Shula (averageness, inability to beat Auburn), Croyle’s only football sin was that he could not stay healthy. He was a good quarterback always teetering on the edges of greatness, but it seemed as though an injury would stifle that ascent. A shoulder injury here, an ACL injury there. At times it felt as if he spent more time in rehab than on the field.

But it wasn’t all melancholy and angst. There was an outlying 10-2 season in 2005, a year in which Croyle set the single-season record for passing yards at Alabama. And after a 31-3 dismantling of Florida, Croyle, forearm bulging mid-throw, graced the cover of Sports Illustrated, the caption reading those long-sought, melodious words “’Bama is Back.”

For Croyle, it was a great time to be alive. He was quarterback at Alabama, a station not too far below the governor in Heart of Dixie’s pecking order. To scores of campus co-eds, he was, simply, a dreamboat. They would gaze at his picture show looks, complemented by his dark complexion and wet swoosh of raven hair. Campus was still campus, and Alabama, as it always has been, was plenty o’ fun. Yes, on that resplendent, tree-lined university, Brodie was a celebrity; his name repeated more times in those few short years than any other.

As Croyle reviews his undergraduate years, he says it was an experience he wouldn’t trade but it wasn’t devoid of challenges. “There were so many things I struggled with, personally, spiritually, things I had to grow through and take my journey,” Croyle said. “Things I look back on and think, ‘gah, I wish I wouldn’t have done that.’ Then you look back and go, ‘I wouldn’t be who I am today if those things wouldn’t have happened.’”

Though the curtain would finally fall on his Alabama career and the hundred thousand cheers fall silent, by 2006 he’d accomplished what he told his parents he would do at age 11: He made the NFL.

Forasmuch fame as football elicited, Croyle’s idolatry of the game became a pollutant to his soul.

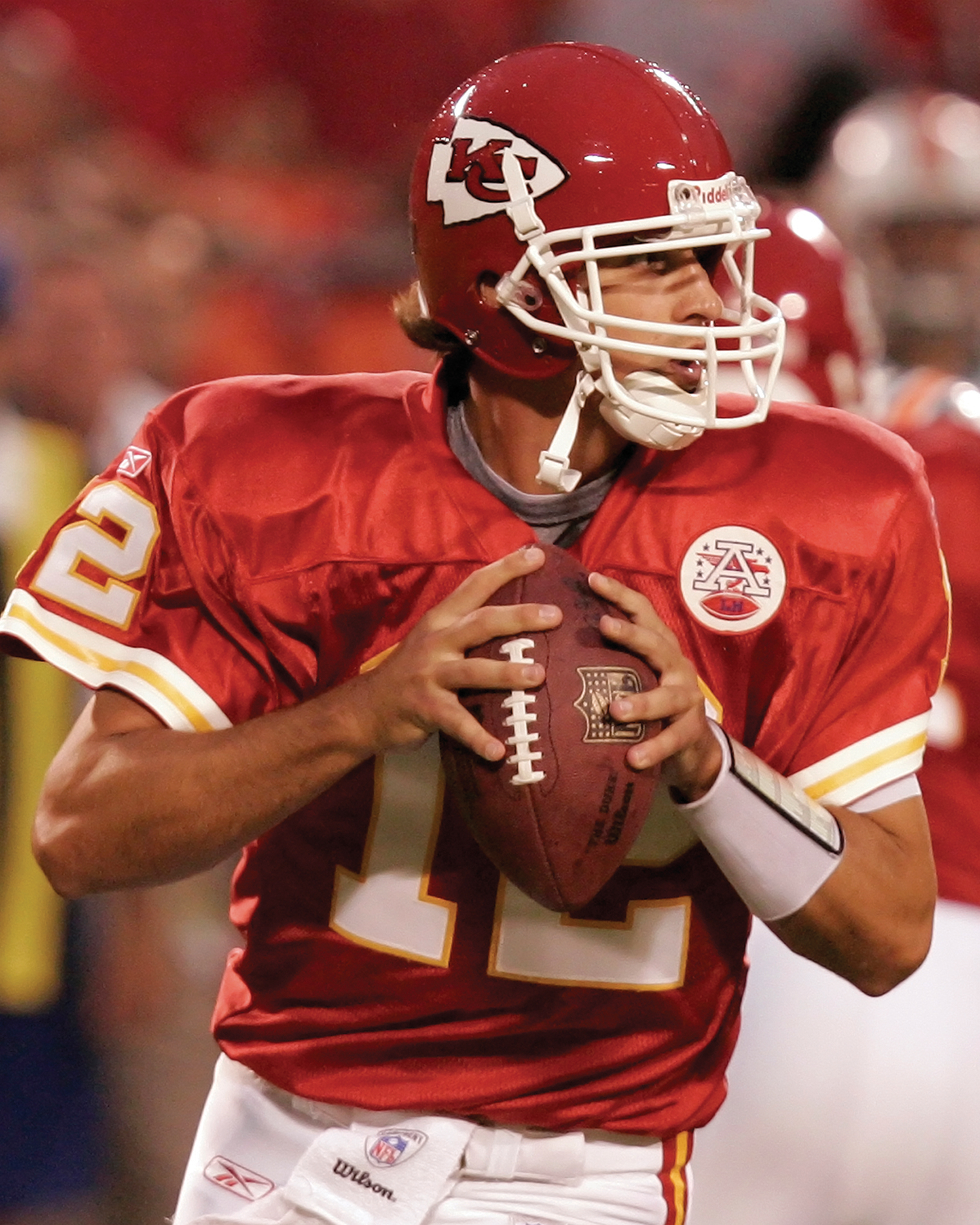

Kansas City and back

Photo courtesy of Brodie Croyle

After being drafted 85th overall by the Kansas City Chiefs in the 2006 NFL Draft, Croyle filled a suitcase and headed for Missouri. He spent 5 injury-riddled seasons in K.C. — his best year 2007 when he threw for 1,227 yards and 6 touchdowns — and his time was largely spent as a role player. Twice, he won the starting job, but injury, that old reaper that seemed to continually interrupt his college career, made its curtain call in the pros.

Since the 8th grade, Croyle had been the man. Now, he had to take on a new role, and with that came a certain amount of humility. He laughs at the couple of instances he was told he was the starting quarterback the morning of the game. “Sunday morning it’s like, ‘hey so-and-so’s not ready … you’re going in to play,” Croyle said. “And it’s like ‘OK great, hadn’t practiced all week! But man let’s go do it!'”

But something good did come out of his time as a backup, a new perspective. “It taught me a valuable lesson in leadership and team-building,” he said. “It taught me to be a leader, you have to serve. For me to use my influence, I had to serve the starting quarterback. I had to serve the starting defense.”

That lesson would later prove to be invaluable, and Croyle views his years in Kansas City as an era that refined him, like rushing water over stones. And though Croyle never achieved greatness on the professional field, Kansas City proved to be a crossroads in his journey to manhood—and one that led him back to the Cross. For the night he noticed — truly noticed — his wife as she poured over Scripture, he was changed. “And that’s truly where I had to set aside what had been my god since I was 11 years old and say, ‘God I want everything it is that you have for me,'” Croyle said. “And it’s in that moment that my realities began to change. That’s where God began to shape and to push and to mold. ‘Now that I’ve got you, I’ve got a plan for you and a purpose for you.'”

Reality began to set in that he would not make a career as an NFL quarterback, and in 2012 Brodie retired from football at age 29. Setting sail on an uncertain voyage without football, he moved back to Alabama and settled tidily back in Tuscaloosa, working for Ingewood Land Company, a real estate and timber company.

Brodie Croyle: Businessman, was his new norm.

From time to time he would visit the Ranch, but he was trying to focus on his family, his work, and his spiritual life. After he and Kelli welcomed their first child, a son, he was learning how to be a dad for the first time. “It was a preparation time in Tuscaloosa,” he said. “I learned a lot about the business aspect of life, the relationship aspect of life. It gave me an opportunity to spend so much time with my wife and my newborn son. I was a new dad so it was a calling on my life.”

Return to the Ranch

Photo courtesy of Brodie Croyle

Business life was good, but it did not have permanence. In 2013, Brodie was led back to the Ranch (he says voluntarily, not because he was promised anything) where he began apprenticing under his dad. Though Brodie didn’t know it, John had a plan in mind: He wanted Brodie to eventually take over as executive director, a secret that he finally revealed to his son some time after he had returned to the Ranch.

Now Brodie’s perspective was shifting again, from watching and understanding the basic nuances of Big Oak life to readying himself for the day his father stepped away from his post. For the last year of John’s tenure, the two men worked and prayed together as the baton was slowly passed. “Instead of saying, ‘hey it’s your show, go run it,’ it’s like, ‘you and I are going to know this, but we don’t have to let everybody else know and that way, we can kind of walk through these decisions together,’” Brodie said.

It was the kind of fruitful, side-by-side journey that both men needed. Finally in 2016, Brodie took over as the Ranch’s executive director. His life, his spiritual journey, had come full circle.

While shaping his overall philosophy of Ranch leadership, Croyle had the smarts and the wherewithal to listen to sage advice. “It was obviously a crash course in learning how things work, trying to figure out what works for my dad and how to plug my personality into it — because we are different people. We’re very different people and we go about things different ways,” Croyle said. “I had a very wise man who told me, ‘if you try to do things his way, it won’t work. You make sure you do it the way God’s given you gifts. Because he put (John) in his place for the Ranch to grow to that point, he’s put you in this place for it to grow moving forward. So you make sure you be authentic and you lead authentic.'”

He has. Among the current highlights at Big Oak Ranch, there is one new home nearing completion, construction beginning on two additional homes, a college and career ministry (ASCEND) officially launching this Fall, and expansion efforts consistently underway for Big Oak Cattle (a program providing a self-sustaining, naturally-raised, beef production system for feeding the Ranch families, which is currently running 300-head). In addition, the newly developed outreach ministry of Big Oak, Planting Oaks, exists to help like-minded individuals begin Christian children’s homes by sharing with those committed to this call insights gained from their experiences, the knowledge they need to sow the seeds of their ministry and the support throughout each stage of growth.

Planting Oaks is currently serving 40 established or soon-to-be established ministries and is actively working to expand its reach and impact. Much growth is taking place to accommodate the increasing number of children needing a safe, loving home and the chance to realize and fulfill God’s plan for their lives. There are 25 staff members and 16 sets of houseparents pulling the wagon and ministering daily to more than 150 children.

As Croyle says, “we get to see God’s beauty on display every day.”

In an ideal world, “success” would mean no need for places like Big Oak Ranch; that adults far and wide would treat children the way they ought to be treated. Of course, this is not the case. Big Oak is growing at such a rapid pace because, as Brodie says, it’s easier to give up. “Where it took us 44 years to build the first 10 homes at the Boys’ Ranch it’ll take us less than 10 to build the next 10,” Croyle said.

The verse that once inspired John to name the Ranch comes from the Book of Isaiah, Chapter 61, Verse 3: “to bestow on them a crown of beauty instead of ashes, the oil of joy instead of mourning, and a garment of praise instead of a spirit of despair. They will be called oaks of righteousness, a planting of the Lord for the display of his splendor.”

Brodie himself is an embodiment of that passage. He has seen the beauty and the ashes in his own life. For many years, the football façade hid a sorrow within, an unsatisfied spirit that would never find rest. “There are a lot of things that are fun about playing in front of 100,000 people or playing in front of millions of people on TV, or being on covers of Sports Illustrated, but there is emptiness,” Croyle said. “It’s not filling it, but at that point in time you are so consumed with you, that you don’t realize what empty is so you try to fill it with the next thing.”

He realized that the ruins he’d made of his life could only be built back through relationship and stepping into the life and light God has for him. “I can tell you pursuing you can’t buy you happiness,” Croyle says. “But, man, when you step into what God has truly put you on this Earth to do, there is a peace that passes all understanding. There’s a joy that can only come from a Heavenly Father who’s perfect. To get to lead 150-plus kids and to let them know where they came from doesn’t define them, and to see them step out of bondage, to see them step out of the pain or what their parents and the world tells them they are capable of and to see them step into who God says they are, it’s a good day. That’s a really, really good day.”

Croyle has kept his promise to his wife. He’s become the man he said he would. Yes, he did become the starting quarterback for the Kansas City Chiefs, but that only lasted awhile. Now Croyle sees the value of tackling things of eternal significance — investing in the soul of a child.

“To get to do this with my wife, with my children, and I get to work with the best people in the world,” Croyle says. “I say it with true humility, it’s the greatest honor of my life.”