The Ultimate National Championship Preview: Joe Burrow vs. Trevor Lawrence is an all-time quarterback duel. Get used to it

When you close your eyes and imagine the platonic ideal of a national championship game, 14-0 LSU vs. 14-0 Clemson is the kind of matchup you might dream of. And the starting quarterbacks in that dream are probably going to look a whole lot like Joe Burrow and Trevor Lawrence.

In fact, it might be impossible to dream up a more fitting or intriguing QB duel on college football’s biggest stage even if you tried. Two prolific, prototypical talents – polished, athletic, savvy, NFL-ready. One a late-blooming savant who just recorded the most lopsided victory in Heisman history. The other a prodigy with a 25-0 record as a starter and a championship win already under his belt. Both bound for the No. 1 overall pick in the NFL Draft and long, lucrative careers as face-of-the-franchise types at the next level.

It’s the kind of blockbuster that, if it lives up to the hype, has the potential to go down with the likes of Leinart-Young in college lore and grow in stature as Burrow and Lawrence mature into pro stars. At the national championship level, it’s also the new normal.

One of the ironies of recent championship history is how surprisingly few heavyweight QB duels there have been. In the BCS/Playoff era (since 1998), only two title games have featured 2 future 1st-round picks behind center – Leinart-Young in 2005 and Tebow-Bradford in 2008 – and only a handful of other have pitted Heisman finalists: Chris Weinke vs. Josh Heupel in 2000; Ken Dorsey vs. Eric Crouch in ’01; Leinart vs. Jason White in ’04. The names don’t exactly ring out through history. Nor do the games, which are remembered (if they’re remembered) essentially as slugfests and blowouts.

The arrival of the Playoff and the triumph of the spread revolution is on the verge of changing that. It already has: In many ways, the highly anticipated Burrow-Lawrence showdown is a reprise of last year’s championship pitting Lawrence and Tua Tagovailoa, another supernova talent at the helm of a record-breaking offense who arrived to the same acclaim reserved for Burrow this year. To get to the big one, Burrow and Lawrence had to outgun another pair of Heisman finalists, Jalen Hurts and Justin Fields, coming off wildly productive seasons of their own.

Collectively, they signal that the days of the “game manager” at the pinnacle of the sport are over. Under the right circumstances, an otherwise talented team might be good enough to ride a Connor Cook, Jake Browning, Kelly Bryant or Ian Book to the semis before they’re forced to face the music, or possibly even a Jalen Hurts or Jake Fromm all the way to the gates, if the right pieces fall into place. (Alabama had those pieces with Hurts behind center in 2016 and ’17; Oklahoma decidedly did not this time around.) But to win it all? In 2020, and for the foreseeable future, finishing the job against a Playoff-caliber defense requires a Deshaun, a Tua, a Trevor, capable of challenging blue-chip secondaries with next-level arm strength and athleticism. It means having a certified dude.

Burrow is that dude. Lawrence is that dude.

And even if the final score in New Orleans can only reflect it for one of them, the odds of an instant classic that stands to enter the realm of mythology over the coming years have rarely been higher. That’s what a championship game should be. At this rate, it won’t be long before we’ll forget it was ever any other way.

Trevor Lawrence beat Ohio State with his legs and arm in the Playoff semifinal. Credit: Mark J. Rebilas-USA TODAY Sports

When Clemson has the ball

[table “” not found /]

* * * * *

As if there was ever any doubt, sophomore QB Trevor Lawrence reinforced his status in the Fiesta Bowl as the sun around which the Tigers’ entire offense orbits. Against the best defense he’s seen to date, Lawrence rallied from a 16-0 deficit and a nasty hit to the head to account for 366 total yards and 3 scores, including the eventual game-winning TD pass with just under 2 minutes to go. That capped a drive on which Lawrence was 3-for-3 for 83 yards with the season on the line, in the face of the first 4th-quarter deficit of his young career.

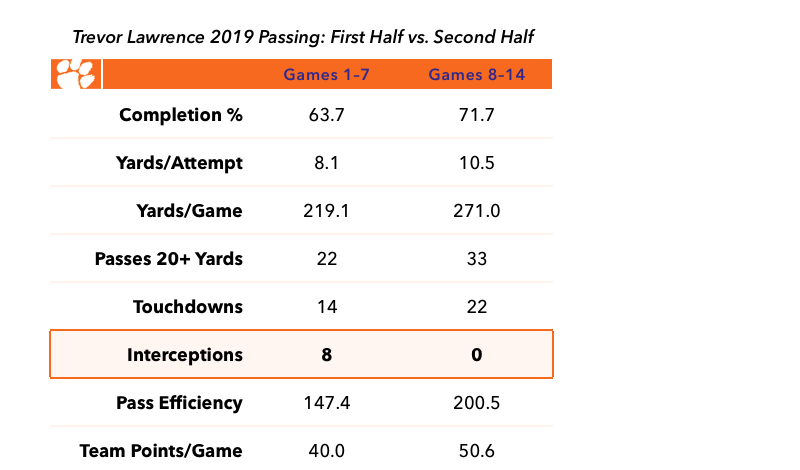

The win over Ohio State unfolded much like his 2019 campaign as a whole: Sketchy start, rapid turnaround, dominant finish. Over the first half of the season, Lawrence looked ordinary and occasionally even reckless, serving up twice as many interceptions in Clemson’s first 7 games (8) as he threw in all of 2018 as a true freshman. The defense carried the day in September wins over Texas A&M (24-10) and North Carolina (21-20) — still the only 2 outings since Lawrence was promoted to the starting job that the Tigers have come up short of 400 yards of total offense — while the national conversation around the preseason Heisman front-runner tended to dwell on what was wrong with him.

Suffice to say no one is asking those kinds of questions anymore. Since mid-October, Lawrence has been virtually flawless:

The left column essentially eliminated Lawrence from the Heisman race at midseason, but the right column is a picture of an acclaimed young talent living up to the hype and then some. His current run of 202 consecutive attempts without an INT is the longest active streak in the country; his overall passer rating over the same span is also the nation’s best, narrowly eclipsing even Joe Burrow’s. Ditto for the film eaters at Pro Football Focus, who graded out Lawrence as the nation’s highest-rated passer over the second half of the season. ESPN’s QBR metric he’s graded out at 92 or higher (out of a possible 100) in 6 of the past 7 games.

He is who we thought he was.

In fact, with his unexpected emergence as a runner, Lawrence might actually be more than we thought he was. In general, his return to form as a passer has coincided with a quietly increased role on the ground, where he’s run for more than 600 yards (not including sacks) and 8 TDs on the season after accounting for less than 300 yards and only 1 TD as a freshman. Against Ohio State, specifically, Lawrence offset a mediocre outing for prolific RB Travis Etienne by taking on the lion’s share of the rushing output himself, setting career highs for carries (13, minus sacks) and yards (132) opposite a loaded OSU defense. Roughly half of that number came on a breakaway, 67-yard touchdown run late in the 2nd quarter that kept Clemson within striking distance at the half and permanently debunked his rep as a statuesque pocket type.

TREVOR LAWRENCE TURNS ON THE BURNERS #CFBPlayoff pic.twitter.com/x5FrKRjYqt

— ESPN (@espn) December 29, 2019

Who knew Lawrence’s game included an option to hit the gas in the open field? Not Ohio State, clearly — his designed runs are most likely to come in short-yardage and red-zone situations, and before that one, his longest run of the season had covered just 28 yards. But the Buckeyes got the message, a little too well; by crunch time, their newfound respect for Lawrence’s legs cost them dearly in the passing game, when Etienne slipped easily behind over-pursuing OSU linebackers for the go-ahead/game-winning touchdown as they were suckered by an apparent QB run action on 1st-and-10:

Trevor Lawrence hits Travis Etienne with a pop pass to give Clemson to lead with less than two minutes left! #ALLIN #CFBPlayoff pic.twitter.com/8SrmB2iEtj

— Sports Daily (@SportsDGI) December 29, 2019

The moral is straightforward enough: Work too hard to take away any particular aspect of the Tigers’ attack, and they’ll beat you with another. Clemson is 1 of only 3 Power 5 offenses this season (along with Ohio State and Oklahoma) to eclipse 3,000 yards rushing and passing, a testament to its balance under co-coordinators Jeff Scott and Tony Elliott, who have been on staff since 2008 and 2011, respectively, and shared the OC job since 2015. (Monday’s game will be Scott’s last at Clemson before he leaves for the top job at South Florida.)

Etienne leads the nation in yards per carry among players with at least 100 attempts, and will leave as the first I-A/FBS back ever to average at least 7.0 ypc on 100+ carries in three consecutive seasons. Seven wide receivers have hauled in multiple touchdowns. The senior-laden offensive line leads the nation in Football Outsiders’ metrics for both line yards per carry and opportunity rate, as well as posting the ACC’s best sack rate. This season hasn’t been a quantum leap over previous Clemson offenses in the way LSU’s has been, but there is nothing this group doesn’t do well and no stage or in-game situation in which it has anything left to prove.

On the other side, though, there are a couple of silver linings for LSU’s defense that don’t necessarily show up in the statistical tale of the tape. One, its blue-chip personnel: Virtually the entire starting lineup arrived as top 100 prospects in their respective recruiting classes, the kind of talent that poses more potential 1-on-1 matchup problems than the numbers alone suggest. And two, it’s playing its best football of the season down the stretch: The Tigers’ past 3 opponents, Texas A&M, Georgia and Oklahoma, all finished with season lows on the scoreboard while coming in more than 100 yards below their per-game averages for total offense.

That’s not to suggest Dave Aranda’s group somehow evolved overnight into a vintage LSU defense circa 2011; this is substantially the same outfit that helped to keep things a lot more interesting than they should have been in shootout wins over Texas (38 points, 530 yards), Florida (28 points, 457 yards), Alabama (41 points, 541 yards), and especially at Ole Miss (37 points, 614 yards), a red-alert collapse in the 10th game of the season. But like Lawrence, it has responded by raising its game to a championship level. Since the debacle in Oxford, Aranda’s D as a whole has arguably played as well as any unit in college football — LSU’s offense notwithstanding, of course.

The make-or-break question for Aranda’s game plan — as well as for pro scouts sizing up the abundance of talent on the field — is on the outside, where LSU’s supremely confident, island-dwelling cornerbacks, Derek Stingley Jr. and Kristian Fulton, will be manned up against Clemson’s long-striding, gravity-defying wideouts, Tee Higgins and Justyn Ross. Last year, Higgins and Ross posterized Alabama’s secondary for 234 yards and a pair of long touchdowns on 9 catches, each one seemingly more jaw-dropping than the last. This year, they’ve replicated their combined 2018 production in terms of yards (1,904) and touchdowns (21) almost exactly. At their best, their catch radius can seem almost infinite.

Against Ohio State, though, Higgins and Ross struggled with the physicality of the Buckeyes’ NFL-bound corners, Jeffrey Okudah and Damon Arnette, who (like Stingley and Fulton, future 1st-rounders in their own right) are listed at 6-feet and 190 pounds or better. They failed to generate any downfield separation, finishing with a pedestrian 80 yards on 8.0 per catch — half their season average on both counts — while spending long stretches in the injury tent. Higgins and Ross are expected to be at full speed Monday, and have repeatedly proven their ability to win the kind of mano-a-mano, jump-ball battles in which LSU’s corners, Stingley especially, excel. Holding them in check won’t decide the game by itself, as OSU can attest. But it will make Lawrence and Etienne’s nights that much more difficult.

Key matchup: Clemson RB Travis Etienne vs. LSU DB Grant Delpit.

Is Delpit an All-American, or a disappointment? A little of both, depending on whom you ask.

On the awards circuit, at least, Delpit fulfilled the preseason hype, bringing home the Thorpe Award as the nation’s best defensive back while also being voted a consensus All-American for the second year in a row. The film, on the other hand, told a very different story, one in which most close observers didn’t consider him to be even the best defensive back on his own team. The hardware was hard to square with Delpit’s actual production, which dipped significantly compared to 2018 amid season-long struggles with missed tackles and nagging injuries. His tape against Alabama, and squaring up against jumbo-sized RB Najee Harris, in particular, was a major red flag.

Much of Delpit’s apparent regression has been chalked up to shoulder and ankle injuries; he says he’s fully recovered and goes into the title game feeling better than he has all season. Etienne, a slippery, Alvin Kamara-like back with deceptive strength and balance to complement his after-burners in the open field, will certainly test that premise: Per Pro Football Focus, no other FBS player this season broke more tackles or averaged more yards after contact.

https://twitter.com/PFF_College/status/1207778472808071173?s=20

Frankly, Etienne getting snubbed for national honors this postseason was at least as bizarre as Delpit winning them. But there’s still one more chance to prove the voters right.

When LSU has the ball

[table “” not found /]

* * * * *

LSU’s offense needs no introduction: The out-of-nowhere ascendance of the Tigers’ passing game is The Story of the 2019 college football season, one that exploded like the Big Bang in September and has only continued to accelerate. The Tigers scored 42 points against Florida, 44 at Alabama in the defining game of the regular season, 50 against Texas A&M in a rout that was even more brutal than the final score suggested, 37 against a Georgia defense that routinely stuffed opposing offenses into suitcases and 63 against Oklahoma in the most ferocious Playoff beatdown yet.

It’s the highest-scoring attack in SEC history, the most prolific in terms of yards per game and per play, the first to feature a 5,000-yard passer, 1,000-yard rusher and 2 1,000-yard receivers in the same season, and … well, and so forth, etc. If you’re reading this you know the deal by now. Trying to account for all the milestones LSU’s offense and honorary cajun QB Joe Burrow have surpassed this season is an exercise in futility.

Joe Burrow has thrown 55 TD passes, 4 shy of breaking the all-time FBS record. Credit: Jason Getz-USA TODAY Sports

About Clemson’s defense, maybe not so much. At the same wunderkind LSU offensive coordinator Joe Brady has emerged as a household name, Clemson’s mostly no-name D under coordinator Brent Venables has gone about hitting all of its usual marks without much fanfare. That’s due at least in part to expectations: 2019 was supposed to be a rebuilding year for Venables’ unit after losing all 4 starters from one of the most decorated defensive fronts ever assembled in 2018, as well as 3 more starters in the back seven. Instead, it was right back to business as usual.

Again, Clemson came in at or near the top of the national rankings in pretty much any relevant category you can come up with, including scoring defense (1st), total defense (2nd), yards per play allowed (2nd), and points per possession (1st). In the advanced metrics, it ranked No. 1 according to both FPI and FEI and No. 3 in Defensive SP+. Against the pass, specifically, the Tigers led the nation almost across the board, finishing No. 1 in yards per game allowed, yards per attempt allowed, gains of 20+ yards allowed, and overall pass efficiency. They’re 3rd in tackles for loss and sack rate. They held every regular-season opponent to 20 points or less and Ohio State’s high-octane offense to just 23, less than half the Buckeyes’ season average.

While the numbers held steady, the mass exodus along the front line did yield a philosophical shift. The typical Venables defense at Clemson generates pressure overwhelmingly via the defensive line, a position group that featured 11 eventual draft picks (including 5 1st-rounders) in Venables’ first 8 seasons as DC. This year that has not been the case: 23 of the team’s 42 sacks came via linebackers and defensive backs, including all 4 QB takedowns in the semifinal win over Ohio State. That’s not necessarily a reflection of the talent level up front — sophomore DEs Justin Foster and Xavier Thomas are future stars, as is true freshman DT Tyler Davis, a full-time starter on the interior from Day 1 — but it is a reflection of how Venables has shifted the emphasis from winning 1-on-1 battles in the trenches to scheming up free rushers.

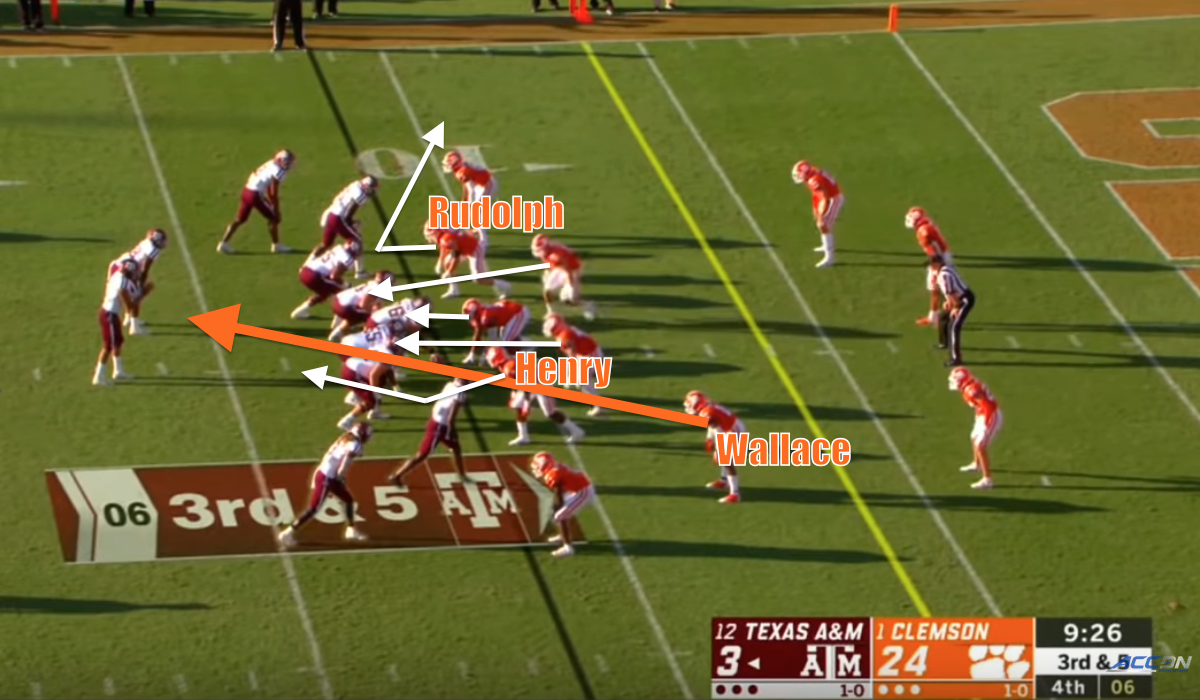

The Fiesta Bowl was one example of that shift; the Tigers’ defensively driven, 24-10 win over Texas A&M in Week 2 was another. Although Clemson only recorded 2 sacks vs. Aggies QB Kellen Mond, it managed to generate a steady diet of pressure that left Mond battered and bloody without an overwhelming effort by the front four, but instead by repeatedly crossing up A&M’s pass protection with 4- and 6-man blitzes out of 2- and 3-down fronts that effectively disguised who would be bringing the heat.

Sometimes it came right up the gut. More often it came from the edges, as on a perfectly disguised corner blitz in the 2nd quarter (Mond never saw it coming) and a 5-man rush in the 3rd that left multiple A&M linemen blocking air as 2 unblocked rushers raced to record the sack. In the 4th quarter, Clemson clinched the game on a similarly unorthodox blitz, this one involving a single down lineman in the red zone:

On paper, the Aggies are fine here: Even with the lone RB releasing immediately into a pattern, there are still 5 blockers to account for 5 rushers. The problem is that they failed completely to account for who the 5th rusher would be. To the left of the formation, DE Logan Rudolph peeled off of his pass rush to carry the back into the flat, leaving A&M’s left tackle, Dan Moore Jr. (No. 65 below), alone to block air; meanwhile, the all-out rush up the middle successfully occupied the interior line, leaving RT Carson Green (No. 54) to handle both DE K.J. Henry (No. 5 for Clemson) and nickel rusher K’Von Wallace (No. 12), who disguised his intentions perfectly before the snap. The result: Another free run at Mond, a panicked heave, scoring threat averted, game over, drive home safely.

Kellen Mond 17/31 with 1 really bad interception pic.twitter.com/xAbYpowAcn

— Simple Man Radio (@SimpleManRadio) September 7, 2019

That is indeed one really bad interception. But when the alternatives are eating another sack or chucking the ball into the 11th row, and the quarterback is forced to make that decision in the split-second between receiving the snap and suddenly realizing he’s a sitting duck, it’s hardly an inexplicable one. Mond recognized too late that Rudolph attempting to run with RB Isaiah Spiller could be a mismatch; he just didn’t have time to set his feet and put the ball where it needed to be.

Obviously, Joe Burrow is not Kellen Mond — his casual mastery of coverages is his greatest asset, right up there with his deadly downfield accuracy. He’s in the midst of the most efficient passing season on record. He’s not going to be late to spot a mismatch, and he’s not going to be easily rattled by a free rusher (or rushers) in his face.

Joe Burrow hits the quick slant on the A gap blitz and Ja’Marr Chase proves why he’s a top WR in the 2021 class. pic.twitter.com/WjThK7PJ2d

— Rob Paul (@RobPaulNFL) November 17, 2019

Still, the list of quarterbacks who have succumbed to Death by Venables is a long and distinguished one: In Clemson’s past 3 Playoff games, the defense has recorded 5 interceptions and a dozen sacks against opposing quarterbacks (Ian Book, Tua Tagovailoa and Justin Fields) who came in with an undefeated record as starters. The Tigers have allowed an average of 13 points in those games, and a single touchdown after the first quarter. If any college defense is capable of giving Burrow and Brady a run for their money, this is the one.

Key matchup: LSU QB Joe Burrow vs. Clemson LB/Edge/SS Isaiah Simmons

OK, yes, if you really want to get technical about it Simmons is a linebacker — he’s built like a linebacker, he was a unanimous All-American as a linebacker, he won the Butkus Award as the best linebacker in the country. Clemson lists him as a linebacker on its official roster. But what a grave disservice it would be to describe his role in the Tigers’ defense as just a linebacker. The reality is that he has the size, speed, and all-around skill set to line up literally anywhere on the field on any given snap, and does:

https://twitter.com/PFF_College/status/1205317165085265920?s=20

Alright, lining up at multiple positions is one thing; actually making plays is another, and it’s hard to come up with another defender in recent memory who has made as many plays in as many different ways as Simmons over the past two seasons. He’s a little like Tyrann Mathieu … if Mathieu were about 6 inches taller, 50 pounds heavier, and capable of taking on offensive linemen as an edge defender in addition to his work as a blitzer and cover man. He’s a perfectly evolved specimen for 21st Century spread football.

In the following clip alone, you’ll see Simmons 1) tracking down a deep fade route along the sideline as a single-high free safety; 2) erasing a running back in pass protection to finish off a sack as an edge rusher; 3) stringing out an option play and obliterating an open-field block to make the tackle for a minimal gain; 4) running step-for-step with a slot receiver and smoothly breaking up a pass nearly 20 yards downfield; and 5) closing fast on a shallow crossing route and ripping the ball out of the receiver’s hands to force a takeaway:

Clemson's Isaiah Simmons is such a difference-maker, hard not to get Derwin James vibes from him.

He's the do-it-all type every NFL team is looking for right now.pic.twitter.com/dBlYEQ0iyt

— Austin Gayle (@PFF_AustinGayle) December 31, 2019

One way or another, Simmons’ presence has to be accounted for on every play. The most straightforward way to accomplish that is to grind away between the tackles with workhorse RB Clyde Edwards-Helaire, forcing Simmons to play a more conventional, gap-sound box linebacker role as opposed to prowling around in places where the offense doesn’t expect him.

But LSU is hardly a “grind away between the tackles” kind of offense, and Burrow’s capacity for instantly downloading opposing defensive schemes is as freakish in its way as Simmons’ versatility. How deftly he’s able to read and react to Simmons’ location on the fly — and to avoid being baited into the kind of cheap turnover Justin Fields served up in the Fiesta Bowl — promises to be one of the season’s most riveting on-field chess matches.

Special teams, injuries and other vagaries

If the difference comes down to a field goal, LSU has to like its chance with true freshman Cade York, who has quickly asserted himself as a long-range weapon: He was 4-of-5 from 50+ yards out, 5-of-9 in the 40-49 range, and perfect inside of 40. (He has missed four extra points, tied for most in the nation, but that’s in part because he attempted more of them than any other kicker; he still finished second nationally in successful PATs, with 83.) Altogether York led all FBS kickers with 146 points in his debut season, an SEC record for points by kicking. Hardly automatic, but plausibly good from anywhere inside the opposing 40-yard line.

That’s a lot more than can be said for Clemson’s B.T. Potter, a sophomore whose first season on full-time place-kicking duty was an adventure. Potter did flash a big leg, going 2-for-2 from 50+ yards; he also proved to be a wild card from shorter range, including 4 misses inside of 40 yards on 11 attempts. He missed at least 1 field goal try in 8 games.

For all the talent in the return game, neither team has managed to score on a punt or kickoff. Clemson’s Amari Rodgers did house a punt in 2018, but hasn’t come close this year after returning from a torn ACL in record time. He and Derek Stingley Jr. on LSU’s side are big plays waiting to happen; somehow both fan bases are still waiting.

On the injury front, Clemson has been almost suspiciously healthy throughout the season. Rodgers was initially ruled out for the year after tearing his ACL in spring practice, but instead missed only the season opener before suiting up against Texas A&M in Week 2 and in every game since. Otherwise, regular starters have missed a grand total of eight games, half of those via a midseason concussion that temporarily sidelined sophomore DE Xavier Thomas. With Thomas back the entire 2-deep is intact.

LSU hasn’t been quite that lucky, losing starting safety Todd Harris Jr. in September along with a handful of relatively minor injuries to Terrace Marshall, Grant Delpit, and others along the way. But the Tigers still arrive as close to full strength as can be reasonably expected after 14 games.

Marshall, Clyde Edwards-Helaire, and starting OL Damien Lewis are all expected to play Monday after getting banged up in the Sugar Bowl (or in the lead-up to the Sugar Bowl, in Edwards-Helaire’s case), as is senior LB Michael Divinity Jr., who’s likely to start in his first game back since getting hit with a 6-game suspension in early November for failing multiple drug tests. Harris will be the only notable absence, and as well as junior JaCoby Stevens has played in his place — Stevens is essentially LSU’s answer to Isaiah Simmons, capable of lining up at all three levels — at this point it’s not really even that notable.

Bottom line

Dabo Swinney and the Tigers are trying to become the first repeat champion since Alabama in 2011-2012. Credit: Jeff Blake-USA TODAY

How much more do we need to see from LSU to start talking about the 2019 Tigers as one of the great teams in SEC history?

In certain respects, you could argue they’re already there, regardless of what happens in New Orleans. Fourteen wins ties the league mark set by the Alabama teams that played in the National Championship Game in 2015, ’16, and ’18, with 6 of those wins coming against teams ranked in the AP top 10 at kickoff and 4 against teams that are certain to finish there. Their blowout postseason wins over Georgia and Oklahoma are arguably the 2 most impressive performances of the season — not just the most impressive by the same team, but the 2 most impressive performances, period. The offensive transformation has left an indelible mark that will transcend the record books.

One way to keep these sorts of big historical questions in perspective is Sports-Reference.com’s Simple Rating System, which offers a useful, apples-to-apples comparison of teams across different eras. Based strictly on SRS, LSU is easily on the short list of the most dominant SEC outfits of the past 50 years, and with a win on Monday night will likely vault to the top of the list of the best teams in the BCS/Playoff era:

By any measure, the 2019 Orgeron/Burrow Tigers will go in the books as one of the league’s all-time juggernauts. But as Alabama has learned the hard way over the past few years, going out as a champion in the Playoff era is an entirely different question.

LSU owns the better résumé against a more difficult schedule, by far, and the money pouring in on LSU’s side in Vegas speaks for itself. But at this point on the schedule Clemson is the known commodity: The Tigers have been on this stage before, owned it, and never left any room for doubt that they would be back.

They earned that return ticket by toppling a loaded-to-the-gills Ohio State team that probably deserves juggernaut status in its own right. They have a generational quarterback, a perennially top-ranked defense, blue-chip depth at every position, and no significant weaknesses outside of (maybe) the kicker. If this isn’t Dabo Swinney’s best team, it’s only because last year’s champs set an impossible standard.

Winning would render the distinction meaningless, anyway. Clemson is very much in dynasty territory, where individual seasons tend to blur together. A 3rd national championship in 4 years would elevate the Tigers into some truly rare historical air, joining Notre Dame (1946-49), Nebraska (1994-97), and Alabama (2009-12) as the only programs to pull the feat since the introduction of the AP poll, in 1936.

Thirty consecutive wins would move them into a tie for the 6th-longest streak since World War II, with the epic 34-game runs in the last decade by Miami (2000-02) and USC (2003-05) well within reach and no end in sight. Trevor Lawrence is en tow for another title run in 2020 and another banner recruiting class is on the way.

Maybe Joe Burrow is the transcendent talent that stops that train dead in its tracks. In any almost other year, against almost any other opponent, it would be insane to suggest otherwise. But we’ve been here before — transcendent quarterback, record-breaking offense and all — and we have pretty good idea now how it ends: With Dabo and his precocious quarterback hoisting the trophy. The team that manages to write a different ending really will have to be one of the greatest of all time.

PREDICTION: Clemson 36, LSU 34