The Big Championship Preview: Clemson has the higher ceiling, but will Alabama’s D give Deshaun Watson time to reach it?

By Matt Hinton

Published:

In college football, rematches on the sport’s biggest stage are exceedingly rare. In the BCS/Playoff era, there has never been a championship rematch — since 1998, only five schools have earned repeat bids to the title game in the first place, and none faced the same opponent on both trips.

Going back further, no two teams have both closed at No. 1 and No. 2 in the final Associated Press poll in consecutive seasons since Notre Dame and Miami did it in 1988-89, before the concept of a true “championship game” existed. No two teams have faced each other with both sitting atop the poll in back-to-back years, at any point on the calendar, since Miami and Oklahoma in 1986-87. The only other time it happened was in World War II. One team putting together that kind of run over multiple seasons is difficult enough; two, coinciding, is almost unheard of.

So regardless of how it unfolds, Monday night’s championship rematch between Alabama and Clemson qualifies as historic: Just to get to this point, the Tigers and Crimson Tide have had to run historic, parallel gauntlets over the past two years, rolling up a combined 46-2 record in the regular season, a 4-0 mark in conference championship games, and a 4-0 run in semifinal dates against other (ostensibly) elite opponents. In the latter category, all four of those wins have come by at least 17 points, leaving no doubt which two teams had earned their reservations in the finale.

Personnel-wise, their consistency is all the more impressive considering how just how much the current editions had to replace from the outfits that squared off last year in Arizona. These are substantially the same teams despite a mass exodus from both lineups: Alabama won that game in thrilling fashion, then bid farewell to its starting quarterback, Heisman-winning tailback, longtime defensive coordinator, and seven starters from the nation’s most dominant defense; this year, it’s back, again, largely on the strength of the nation’s most dominant defense, under first-year DC Jeremy Pruitt.

Clemson still has the headliner of last year’s tilt, Deshaun Watson, but also lost seven defensive starters from that game to the draft; still, the Tigers arrive boasting a top-10 defense, fresh from a 31-0 trouncing of Ohio State that ranks as the best defensive performance of Dabo Swinney’s tenure as head coach.

Faces change, the beat goes on. If the second go-round is anywhere near as memorable as the first, keep them coming.

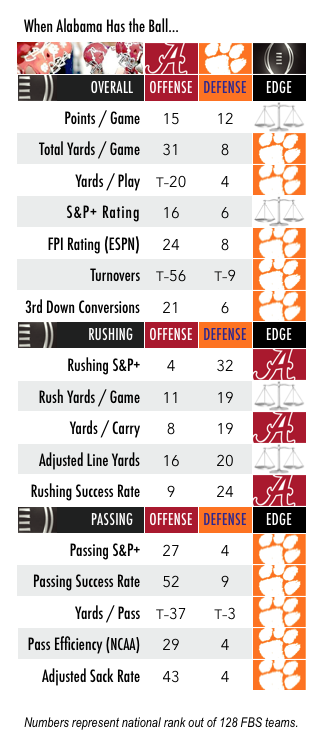

When Alabama Has the Ball

This is a strange thing to say approaching the 15th game of the season, but at the moment it’s hard to know quite what to expect from Alabama’s offense. The semifinal win over Washington was Jalen Hurts’ worst outing yet as a passer, a 7-for-14, 57-yard dud that led directly to the decision to toss Lane Kiffin overboard at the eleventh hour and hand over play-calling duties for the championship to Steve Sarkisian. It’s hard to imagine an odder or more inconvenient time for an identity crisis.

So what now? Saban’s not about to overhaul the playbook in the course of a week — of the many possibilities that might cause Clemson’s coaches to lose sleep this weekend, preparing for, say, the triple option won’t be one of them — and we’ve all been assured that Sarkisian has a firm grasp of the offense since joining the staff in September as an “analyst,” whatever that means. (Sarkisian was reportedly paid $35,000 and tasked specifically with strategizing for third downs.) The situation might seem more melodramatic from the outside, where media and non-Bama fans are drawn to any narrative that breaks up the monotony of another by-the-book finish from the sport’s reigning dynasty, than it does within the team.

Players, naturally, insist they’re down with the change, and claim practices are going even “faster and smoother” than usual. If anyone deserves the benefit of a doubt in the wake of an abrupt personnel change, it’s Saban, who seems to have carved out a role for Sarkisian months ago with an eye toward precisely this scenario. But the timing is … uh, weird, to say the least.

The easy answer, of course, is that Bama will do what Bama has always done, and what most of the fan base was screaming for Kiffin to do when the play-calling got a little too pass-happy in the second and third quarters of the Peach Bowl: When in doubt, run the dang ball. Statistically, Clemson’s defense isn’t as stout against the run as Washington’s, which the Crimson Tide’s mammoth offensive line succeeded in pushing around for 289 yards (not including sacks) on 6.1 per carry. Bo Scarbrough, a Tuscaloosa native, was a revelation against the Huskies, finally fulfilling his birthright as the next huge, terrifyingly athletic Alabama running back after battling injuries for most of the past two seasons. Spread tendencies notwithstanding, Scarbrough and fellow sophomore Damien Harris fit perfectly into the Tide’s recent lineage of complementary, thunder-and-lightning workhorses; add Hurts on the zone read, and this remains the most productive backfield of the Saban era at nearly 250 rushing yards per game.

The easy answer, of course, is that Bama will do what Bama has always done, and what most of the fan base was screaming for Kiffin to do when the play-calling got a little too pass-happy in the second and third quarters of the Peach Bowl: When in doubt, run the dang ball. Statistically, Clemson’s defense isn’t as stout against the run as Washington’s, which the Crimson Tide’s mammoth offensive line succeeded in pushing around for 289 yards (not including sacks) on 6.1 per carry. Bo Scarbrough, a Tuscaloosa native, was a revelation against the Huskies, finally fulfilling his birthright as the next huge, terrifyingly athletic Alabama running back after battling injuries for most of the past two seasons. Spread tendencies notwithstanding, Scarbrough and fellow sophomore Damien Harris fit perfectly into the Tide’s recent lineage of complementary, thunder-and-lightning workhorses; add Hurts on the zone read, and this remains the most productive backfield of the Saban era at nearly 250 rushing yards per game.

Beyond the numbers, though, Alabama’s routine dominance in the trenches is hardly a foregone conclusion. Clemson has talent: D-line starters Christian Wilkins, Carlos Watkins, Dexter Lawrence, and Clelin Ferrell were all touted recruits who ranked among the top 100 overall prospects in their respective classes, and all four have flashed first-round potential. They certainly looked the part against Ohio State, holding the Buckeyes to one of their worst games under Urban Meyer in terms of rushing yards (88) and yards per carry (3.8) en route to the shutout.

In large part, those numbers were the result of 11 tackles for loss, which is par for the course for Clemson under defensive coordinator Brent Venables; with three more on Monday night, the Tigers will finish with more TFLs than any other defense nationally for the fourth consecutive year since Venables arrived from Oklahoma.

And although many of the faces have changed in the meantime, Clemson looked the part in the last meeting against Alabama, too, holding the Tide well below their season averages on the ground while sacking pedestrian QB Jacob Coker five times.

To his eternal credit, Coker still managed to deliver the game of his life (335 yards, two touchdowns, zero turnovers) when his team needed it the most. But Coker was a fifth-year senior rallying his team in a tit-for-tat shootout. Hurts is a true freshman — an accomplished freshman, yes, a poised freshman, but still: a freshman — who’s taken the field with his team trailing after halftime just once.

It’s possible, given the chance, that Hurts is fully capable of passing the Crimson Tide out of trouble even if he doesn’t have the kind of run support he’s accustomed to. Based on the most recent returns, and given the turmoil of the past week, they’d rather not find themselves in any position to find out.

Key Matchup: Alabama LT Cam Robinson vs. Clemson DE Clelin Ferrell

Robinson owns the name recognition in this matchup, having held down the left side of the Alabama line in all 43 games since he arrived on campus; he’ll leave after No. 44 as a consensus All-American and the consensus favorite to be the first offensive lineman drafted in the spring. Ferrell, on the other hand, is a redshirt freshman in his first year as a starter, and probably the least recognizable member of the Tigers’ formidable front four.

That will change, though, if it hasn’t already in the wake of Ferrell’s breakout performance in the Fiesta Bowl. I first noticed Ferrell’s explosiveness off the edge in September, when he leapt off the film on a handful of disruptive plays in Clemson’s opening-day win at Auburn; against Ohio State, he was a bona fide terror from start to finish, racking up three TFLs (including a sack) and generally harassing OSU quarterback J.T. Barrett all night. In many respects the way the Buckeyes use Barrett in the ground game is similar to the way Alabama uses Hurts, and Ferrell was having none of it.

Here he is on Ohio State’s first possession, embarrassing the Buckeyes’ left guard, Demetrius Knox (No. 78), off the snap on his way to blowing up a bread-and-butter QB sweep on 3rd-and-1:

The loss on that play set OSU back 5 yards on the ensuing field goal attempt, which sailed wide right.

Here he is on Ohio State’s second possession, making a play that shouldn’t even be possible for a 265-pound defensive end against the Buckeyes’ all-purpose speed back, Curtis Samuel, on a jet sweep look that should look very familiar to Alabama fans:

Again, the loss forced a long field goal attempt that, again, sailed wide.

Here the Buckeyes attempted to block Ferrell with unanimous All-American Pat Elflein (No. 65) pulling from the center spot in an effort to open up a running lane for Barrett; this is similar to the way Auburn tried to block him in the opener, with similarly terrible results:

And here they attempted to block Ferrell with a tight end and a running back, with predictable results:

That was on 1st-and-10, and actually qualified as one of Ohio State’s more productive plays due to a defensive pass interference penalty on the receiving end. On obvious passing downs, Venables got more creative. Here, Ferrell came scot-free for one of Clemson’s three sacks on the night courtesy of a well-designed, six-man rush in a 3rd-and-13 situation in the third quarter. Keep an eye on the blitzing middle linebacker, Kendall Joseph, who occupied both Elflein and RG Billy Price, No. 54, to create a lane for Ferrell to arrive untouched into Barrett’s lap:

Alabama’s offensive front is significantly better than Ohio State’s from tackle to tackle, and there’s no active college player better suited to anchoring the blind side than Robinson. Regardless, if the Tide find themselves in third-and-long they’ll quickly realize Ferrell is one of last the players they want to see on the opposite side of the line, too.

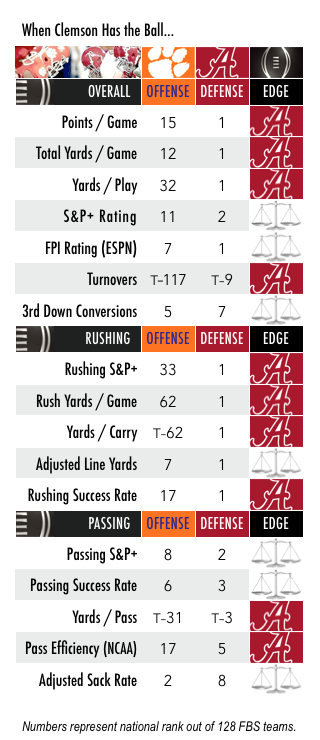

When Clemson Has the Ball

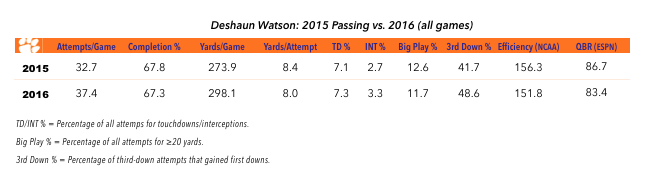

Relative to expectations, Deshaun Watson didn’t quite deliver the flawless, fire-breathing junior campaign the preseason hype suggested. If there’s any doubt, though, whether the Crimson Tide should expect to see the same quarterback on Monday night as the one who lit them up for 405 yards and four touchdowns last year, the final ledger should leave none:

That’s remarkable year-over-year consistency for a college passer, and whatever regression you might discern from the big-picture numbers is largely erased by the fact that Watson was often at his best on the biggest stages. In six games against teams ranked in the final regular-season AP poll, Watson racked up 269 total yards (rushing and passing) against Auburn, 397 yards against Louisville, 430 against Florida State, 588 against Pittsburgh, 373 against Virginia Tech in the ACC title game, and 316 against Ohio State, accounting for multiple touchdowns in each of those games, as well.

Compared to 2015, his pass efficiency rating against ranked opponents improved by more than 10 points. His overall sack rate in all games improved to 2.4 percent, one of the best rates in the nation. Among Power 5 conference QBs, only USC’s up-and-coming wunderkind, Sam Darnold, was brought down fewer times relative to how often he dropped back.

And while his rushing output was effectively cut in half in 2016, that was largely by design, to lighten the weekly wear-and-tear Watson endured as a sophomore against the likes of Syracuse, Wake Forest, and South Carolina. (Prior to the season, Watson also took offense to the flatly wrong notion that he’s a run-first type, which might have contributed to his more pocket-friendly orientation throughout the year.) When necessary — as it almost certainly will be against Alabama — the Tigers won’t hesitate to make the quarterback the engine of the ground game, just as he was over the second half of 2015. This year, against Louisville, FSU, Virginia Tech, and Ohio State, Watson averaged 71 yards rushing on just shy of 16 carries, a better indicator of the kind of workload he’s in for opposite the No. 1 run defense in recent memory.

And while his rushing output was effectively cut in half in 2016, that was largely by design, to lighten the weekly wear-and-tear Watson endured as a sophomore against the likes of Syracuse, Wake Forest, and South Carolina. (Prior to the season, Watson also took offense to the flatly wrong notion that he’s a run-first type, which might have contributed to his more pocket-friendly orientation throughout the year.) When necessary — as it almost certainly will be against Alabama — the Tigers won’t hesitate to make the quarterback the engine of the ground game, just as he was over the second half of 2015. This year, against Louisville, FSU, Virginia Tech, and Ohio State, Watson averaged 71 yards rushing on just shy of 16 carries, a better indicator of the kind of workload he’s in for opposite the No. 1 run defense in recent memory.

In other words: He is who we thought he was. There were more productive quarterbacks this season in terms of yards and touchdowns, and more efficient passers. But in terms of his entire skill set — arm strength, accuracy, mobility, big-game experience, poise under pressure — Watson’s game remains the most potent combination of career production and potential at the college level since Marcus Mariota, at least. There’s a reason the dude’s finished in the top three in Heisman voting two years in a row.

That said, there’s also a reason Watson has plummeted from the top spot in 2017 mock drafts, where he was entrenched throughout the offseason. There are 32 reasons, in fact: That’s the number of interceptions he’s thrown over the past two years, more than any other college QB in that span. Seventeen came this year, with Watson serving up at least one INT in 10 of Clemson’s 14 games; alarmingly, Louisville (3), Florida State (2), Pitt (3), and Ohio State (2) all came away with multiple picks. A few of those have been truly inexplicable. The last of his three picks against Pitt, in particular, was an uncharacteristic, uncalled-for disaster that turned an apparent game-clinching scenario for Clemson in the fourth quarter into a lifeline for the Panthers, who went on to pull one of the upsets of the year.

Taken as a whole, the pick parade is reminiscent of the 18 interceptions Jameis Winston threw in his post-Heisman season at Florida State, in 2014, and — like Winston at FSU — a reflection of just how much the offense relies on Watson’s ability and willingness to take chances downfield.

It’s also a reflection of his Winston-esque capacity to turn his mistakes into mere footnotes to his brilliance. The lapse against Pitt stands as Watson’s only regular-season defeat in 32 career starts, in which he also (by the way) threw three TD passes en route to the single-game ACC passing record; Clemson scored 42 points in the loss. Including rushing scores, Watson has yet to play a game in which turnovers outnumber touchdowns.

Of course, Alabama’s blue-chip, boa-constrictor defense is a unique challenge for any quarterback, especially one resigned to working without the benefit of a conventional running game. (The starting tailback, Wayne Gallman, quietly eclipsed 1,000 yards rushing for the second consecutive season. But his overall production declined from 2015, and Gallman’s most notable contribution in last year’s title game came as a receiver. They might get creative with misdirection and pop a long run or two, but as a game plan, the Tigers’ prospects of pounding out a decent living between the tackles against Bama are as bleak as everyone else’s.)

The Tide’s M.O. all year has been to apply relentless pressure from its corps of elite pass rushers until opposing QBs either retreat into a shell or eventually crack, opening themselves up to the kind of knockout-blow-via-deflating-turnover that has defined Alabama’s season to date.

Had we not already seen Watson survive and thrive in the eye of the storm last year, we might safely assume he will be doomed to the same fate. But based on that performance, along with everything else we know about him, it’s safer to assume that he’s up for the challenge in a way that no one else Bama might have faced in this game could be.

Key Matchup: Alabama CB Marlon Humphrey vs. Clemson WR Mike Williams

Choosing just one option from Clemson’s receiving corps is like choosing from the menu of an upscale restaurant: In the hands of a capable chef, you can’t go wrong. Each of Watson’s top six targets finished with at least 30 receptions, all but one of whom — deep-ball specialist Deon Cain, who averaged a team-best 19.1 yards per catch — registered a catch rate of 68 percent or better on passes in their direction. Cain is the straight-line, downfield speedster; Artavis Scott and Ray-Ray McCloud are squirrely slot types; tight end Jordan Leggett is a reliable security blanket who excels in the red zone; Hunter Renfrow is the undersize, jack-of-all-trades walk-on who Tide fans remember roasting 5-star cornerback Minkah Fitzpatrick for two touchdowns last year.

Watson’s favorite by far, though, is Williams, a 6-foot-3, 225-pound leaper who returned from a fractured neck in 2015 to establish himself as the nation’s preeminent matchup nightmare against smaller corners.

Williams easily led the team this year in targets (129), catches (90), yards (1,267), and touchdowns (10), emerging in the process as arguably the most coveted wideout in the upcoming draft. More important from Alabama’s perspective, he also gives Watson a confident jump-ball option, capable of routinely coming down with contested catches like this one over Ohio State’s Damon Webb:

… which Watson didn’t have at his disposal in 2015. Williams’ elite catch radius significantly increases the margin for error on that type of throw, a luxury his quarterback has enthusiastically embraced.

No individual matchup on Monday night will have more money at stake than Williams vs. Humphrey, whose similar combination of size (6-1, 196), athleticism, and aggressiveness in run support has him at or near the top of the board for draft-eligible corners, as well.

The knock on Williams is that he’s somewhat inconsistent on routine catches, but Humphrey can be beaten: He allowed multiple big plays in September to Ole Miss’ Damore’ea Stringfellow:

… and A.J. Brown:

… both big, NFL-bound receivers who (like Williams) excel at boxing defenders out like they’re going up for a rebound. Later, Humphrey also gave up one-on-one touchdowns to Texas A&M’s Christian Kirk and, last week, to Washington’s Dante Pettis on identical routes to the back corner of the end zone. If Williams is as quiet in this game as the Huskies’ top deep threat, John Ross, was in the last one, it certainly won’t be for lack of effort on Clemson’s part.

Special Teams, Turnovers, and Other Imponderables

For what it’s worth, the kicking game was the difference for Alabama in last year’s win, thanks to a blocked field goal, a kickoff return for a touchdown, and a surprise onside kick for the ages. But as far as sizing up this year’s game, those big, pendulum-swinging plays mean about as much as the logo at midfield.

On paper, in fact, there’s no discernible special teams edge for either side whatsoever. The place-kickers, Adam Griffith (Alabama) and Greg Huegel (Clemson), both connected on 74 percent of their field goal attempts with longs of 48 and 47 yards, respectively. Alabama punter J.K. Scott does have a much bigger leg than Clemson’s Andy Teasdall, averaging 47.4 yards per kick to Teasdall’s 38.0 and blasting 24 punts that covered at least 50 yards to Teasdall’s four; on the other hand, Teasdall forced more fair catches than Scott, settled for fewer touchbacks, and dropped a slightly higher percentage of his punts inside opponents’ 20-yard lines.

Clemson recorded four blocks on field goals, extra points, and punts, allowing two of its own; Alabama recorded three blocks, allowing one.

Neither team allowed a return, kickoff or punt, for a touchdown.

Excluding a pair of punt return TDs by Bama’s Eddie Jackson, who suffered a broken leg at midseason, neither side scored itself in the return game, either. With Jackson on ice, the only play that separates the Tigers and Tide in this category is Alabama’s return of a blocked punt for a touchdown in the SEC Championship Game.

Given the sheer number of explosive athletes involved in this game, it’s impossible to rule out a random, unforeseen twist in one form or another. If lightning does strike, though (or, in the minds of Bama fans, when lightning strikes) it’s still most likely to be courtesy of Alabama’s defense, the best in a very long time at making big, game-changing, once-in-a-blue-moon plays feel routine.

With Ryan Anderson’s pick-six against Washington, the Tide have scored 11 defensive touchdowns by eight players, almost all of them the result of pressure from the pass rush. That remains the stat of the year. And with Watson’s penchant for high-risk/high-reward bets downfield, there should be opportunities both to improve on last year’s lone takeaway and generate points in the process.

Once More, With Feeling

Of the many ways this game could unfold, a rerun of last year’s blockbuster — an epic, back-and-forth affair featuring 1,023 yards of total offense, 11 touchdowns, and three lead changes after halftime — is, unfortunately, one of the least likely.

Both sides this time are better on defensive than offense; despite Clemson’s up-tempo rep, when it’s on, Venables’ defense is more than capable of holding its own in the kind of slugfest Bama strives for as a matter of course, especially in a situation in which the Crimson Tide would seem to have every incentive to grind the proceedings to a halt.

Regardless of the local spin, the abrupt shift from Kiffin to Sarkisian, barely a week from kickoff, is a concern. And frankly, as solid as he’s been for most of the year, Jalen Hurts isn’t being graded on a curve anymore: His output against the best defenses on the schedule over the second of the season (LSU, Florida, Washington) has been alarmingly one-dimensional. It’s no surprise that Vegas looked at the 85 points these teams scored the last time they got together and then set the over/under for Monday night at 50.5.

Alabama is favored (deservedly) by 6.5 points, and there’s still some chatter about the Crimson Tide’s place among the best college outfits of all-time if they go wire-to-wire as the undisputed No. 1 team in the nation. Defensively, their place in history is hard to dispute.

By now we’ve all seen the script unfold enough times in the biggest games to know exactly what a thorough, convincing Bama victory looks like, and it doesn’t necessarily involve the quarterback doing a whole lot aside from curbing dumb mistakes. As we saw against Washington, it could also involve some combination of Scarbrough, Harris, and/or Hurts patiently grinding Clemson into submission even without much in the way of air support.

Contrary to the way we’re used to thinking and talking about Alabama, though, it might actually be Clemson that comes in with the higher ceiling. The Tigers have been less consistent over the entire season, to put it mildly. At their best, though, they’re arguably the more complete lineup across all phases: If the same team that just waylaid Ohio State shows up in Tampa, it’s easier right now to imagine that group hanging somewhere between 24 and 35 points on Alabama than vice versa, if only because Deshaun Watson is a proven commodity on this stage, against this defense, and his counterpart is not.

If Watson breaks out his Vince Young-in-the-Rose-Bowl routine again, it’s very difficult to know how Hurts will respond.

And maybe he won’t have to. In the end, Bama’s awesome, fire-breathing defense might conquer all, anyway. But I can’t think of anyone else better equipped to slay the beast.

Prediction: Clemson 31, Alabama 26

Matt Hinton, author of 'Monday Down South' and our resident QB guru, has previously written for Dr. Saturday, CBS and Grantland.