The Ultimate Sugar Bowl Preview: A new context for Alabama-Clemson, but for the same old stakes

Alabama vs. Clemson: We’ve seen this show before, twice, with a lot of faces that feature prominently in Monday night’s rubber match and a lot more that have moved on to the next level. We know what this show looks like, and if the first two installments are any indication, the third is going to be dynamic, tense, and a lot of fun. This matchup, specifically, is the one Alabama has been aiming for since the early-morning hours of Jan. 10.

In other respects, though, this time around feels very different, for reasons that have nothing to do with the fact that the collision is a semifinal date rather than the championship. This time of year, winner-take-all is winner-take-all. It’s just difficult to recall a game of this magnitude involving Alabama that most people weren’t reasonably certain that the winning and the taking would be done by the Crimson Tide. Bama’s not an underdog, in Vegas or anywhere else — Bama is never an underdog — but it does arrive with a feeling of vulnerability that’s rare in the Saban era, if not unprecedented.

Consider the context that framed the first two meetings. In 2015, Alabama arrived at the championship game riding an 11-game winning streak, six of them vs. ranked opponents, including a merciless, 38-0 romp over Michigan State in the semifinal; the Tide opened as 7-point favorites against Clemson, which shocked most of the country by taking Bama to the wire in a wildly entertaining, 45-40 loss. Last year, the winning streak was up to 26 straight, and the defending champs were again favored by a touchdown after spending the entire season at the top of every poll in existence. The 2016 Tide were considered so far ahead of the contemporary pack prior to last year’s title game that it seemed just as appropriate to rank them against the greatest college teams of all-time.

This year, not so much. The fact that the Bama juggernaut came up one second short of making good on last year’s promise didn’t diminish its juggernaut status, or stop anyone from installing the Crimson Tide atop the preseason polls, where they were (and largely remained, until the final week of the regular season) an overwhelming choice for No. 1. But the championship loss did leave the door cracked just enough for doubts to begin to creep in after uninspiring November wins over LSU and Mississippi State, and a decisive, 26-14 loss at Auburn knocked the door down. From the other side of that defeat this campaign looks much less impressive: Alabama’s big non-conference victim, Florida State, was a massive disappointment, and both of its wins over ranked opponents were highly competitive slugfests. It didn’t win its own division, much less its conference, and was flatly outplayed by the best team it faced.

Given all that, you could look at the fact that Bama was awarded one of the four golden Playoff tickets anyway as a testament to the strength of its brand more than the strength of this particular team’s résumé, and you wouldn’t necessarily be wrong if you did. (The point spread in Bama’s favor is certainly due to the brand.) It’s also a testament to the fact that, regardless of the other team on the field, Nick Saban’s team is still far more likely than not to be the best team on it.

Clemson, the top seed in this year’s proceedings, might take the opportunity refute that assumption all over again — this time without a once-in-a-generation quarterback at its disposal — changing the contours of the how the rest of the country views the Crimson Tide for the third year in a row. Or the Tide could do what they’ve done so many times over the past decade and reassert their authority as the sport’s smashmouth overlords. Either way, the stakes are as high as ever.

WHEN CLEMSON HAS THE BALL …

Kelly Bryant is not Deshaun Watson, obviously — that would be terrifying, and possibly suspicious — but he’s not so far off that Clemson has had to change anything it does offensively. He’s the same type of quarterback: Same rangy frame, same placid demeanor, same loping stride in the open field. As runners, they’re almost indistinguishable; like Watson, Bryant is a lot thicker in reality than he looks (both check in around 220 pounds) and routinely handles about a dozen carries per game, excluding sacks. His rushing output this year was virtually identical to Watson’s in 2016, and if you really want to get technical about it Bryant’s numbers are slightly better.

Credit: Jeremy Brevard-USA TODAY Sports

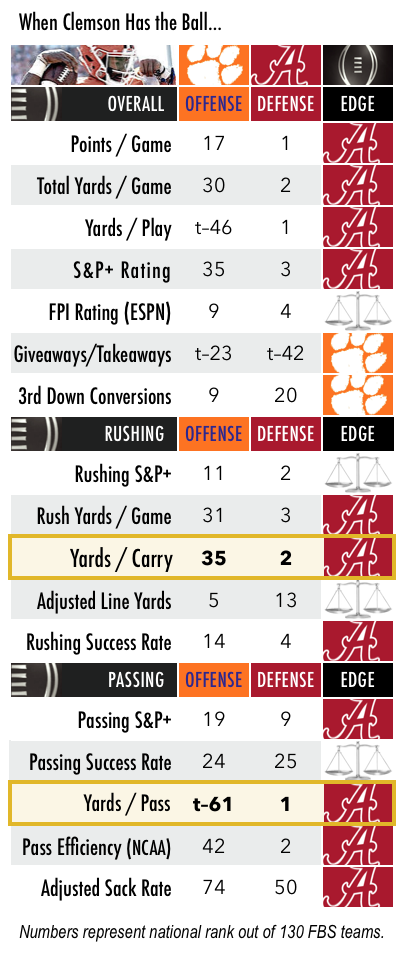

In certain ways he was Watson’s equal as a passer, as well, effectively matching his predecessor in terms of completion percentage and third-down conversions while improving on Watson’s alarming interception rate. In other ways, though, the offense has clearly been more restrained in the transition to Bryant, throttling down the tempo and generally putting the ball in the air less often. And in terms of downfield explosiveness, the drop-off has been palpable:

Those splits were predictable, and not only because Clemson traded one of the great deep-ball artists of the decade for an unproven passer who’s probably a marginal pro prospect at best. On the other end of those throws, the Tigers have also badly missed last year’s top two targets, Mike Williams and Jordan Leggett, future draft picks whose combined production as seniors (2,097 yards, 18 TDs on 144 catches) is a close match with the team’s overall decline in each of those columns.

No one has emerged to fill either of those roles. The top returning receiver, Deon Cain, saw his per-catch average plummet this season, from 19.1 yards a pop to 12.7, and actually finished with fewer yards as the team’s most frequent target (659) than he did last year coming off the bench (724). If you want to explain why Clemson averaged a full touchdown per game less this year against Power-5 opponents, the absence of a reliable downfield connection is the place to start.

The ground game has fared better, and while it hasn’t nearly made up for the deep-passing gap it has turned out to be an improvement over 2016 in just about every way that matters. Much of the credit for that belongs to the offensive line, which returned four of five starters, remained intact with minimal shuffling, and ranked fifth nationally in Adjusted Line Yards; accordingly, three Clemson linemen (LT Mitch Hyatt, RG Tyrone Crowder, and C Justin Falcinelli) were voted first-team All-ACC by a panel of league coaches and media. But the Tigers have also made efficient use of their backs, most notably Bryant, who often functions as a de facto tailback; excluding sacks, he’s the leading rusher in terms of both yards and carries.

Neither tailback, Tavien Feaster and Travis Etienne, shouldered a full workload for more than a game or two, which kept them from getting much traction outside of the Clemson fan base. But both flashed home-run ability commiserate with their blue-chip grades as recruits — especially a Etienne, a blazing-fast freshman from Louisiana who spurned LSU and seemed to break off a highlight-reel run on a weekly basis over the first half of the season. He cooled off a bit down the stretch, but still averaged 7.2 yards per carry for the year (best in the ACC among backs with at least 100 attempts) and found the end zone in 10 different games.

Neither tailback, Tavien Feaster and Travis Etienne, shouldered a full workload for more than a game or two, which kept them from getting much traction outside of the Clemson fan base. But both flashed home-run ability commiserate with their blue-chip grades as recruits — especially a Etienne, a blazing-fast freshman from Louisiana who spurned LSU and seemed to break off a highlight-reel run on a weekly basis over the first half of the season. He cooled off a bit down the stretch, but still averaged 7.2 yards per carry for the year (best in the ACC among backs with at least 100 attempts) and found the end zone in 10 different games.

What does that mean against Alabama? Historically, not much. As always, Bama ranks among the elite run defense in the nation, and the d-line rotation of Da’Shawn Hand, Raekwon Davis, Isaiah Buggs, and Da’Ron Payne is straight out of central casting. A huge chunk of Clemson’s rushing yards in the previous two meetings came as a result of Watson scrambling; designed runs accomplished very little, as is usually the case. The Tigers aren’t the kind of team that typically tries to line up and physically oppose its will on opposing defenses in any case, and any effort along those lines against the Crimson Tide is probably as doomed as ever.

Relatively speaking, though, the last few weeks of the regular season exposed a few leaks in the front seven, beginning with a season-ending knee injury to senior linebacker Shaun Dion Hamilton in the Tide’s win over LSU. In Hamilton’s absence, the Bama immediately allowed a 54-yard run — the longest against Alabama in more than two years — that set up LSU’s only touchdown in that game, and subsequently struggled (again, by Bama standards) to stop both Mississippi State, which ground out 172 yards rushing and dominated time of possession in a near-upset in Starkville, and Auburn, which followed the same script en route to a comfortable win. Even factoring in the glorified scrimmage against Mercer, the Tide allowed more yards per game rushing in the month of November (149.5) than in any other month of Saban’s tenure.

Compounding that, the drop-off in Alabama’s pass rush from the past two years has been arguably steeper than Clemson’s in the downfield passing game. No one realistically expected the new outside linebackers to match the production of Ryan Anderson and Tim Williams, the best edge-rushing tandem in the nation in 2016, or for Hand to dominate to the extent of Jonathan Allen, who might have been the best player in the country last year at any position. But they certainly expected something from the replacements, who have come up essentially empty: As a group, the outside linebackers have been managed a single sack all year, credited to part-time starter Jamey Mosley. Hand, limited by injuries, has just two; the full-time starter at “Jack,” Anfernee Jennings, has zero, in the same position that produced double-digit sacks last year between Anderson and Christian Miller.

That’s not to say that the Tide can’t still generate pressure — during one midseason stretch they recorded at least four sacks in five consecutive games against Ole Miss, Texas A&M, Arkansas, Tennessee and LSU, with Davis personally getting in on the action in all five games. And historically Alabama’s defense under Saban hasn’t prioritized getting to the quarterback as emphatically as it did the past two years; in the long run those seasons look like the aberrations, and this year’s production looks like par for the course. Still, here’s guessing Bryant prefers the current course to the one that greeted his predecessor.

Huge score for Clemson! Deshaun Watson finds Hunter Renfrow on a 24 yard TD!!! Alabama’s lead cut to 17-14. Heard on @ESPNRadio. #ALLIN pic.twitter.com/J84BvlIWdg

— ESPN Radio (@ESPNRadio) January 10, 2017

Key Matchup: Clemson WR Hunter Renfrow vs. Whoever Is Covering Him: Renfrow is a storybook foil for Alabama — who can resist the appeal of a baby-faced, 5-10 walk-on slaying the most monolithically talented outfit in the sport? — but don’t let the “possession receiver” clichés obscure the fact that the guy’s a legitimate, quantifiable baller. As a junior, Renfrow led all ACC receivers with at least 40 targets in both catch rate (79.7 percent) and success rate (60.9 percent), reflections of his uncanny consistency and efficiency from the slot. Of his 19 third-down receptions this season, 16 moved the sticks, twice as many as any other receiver on the team. He’s as clutch as they come in the college game, and that’s coming from someone who doesn’t even believe in “clutch.”

No one alive needs to be reminded of Renfrow’s skills less than Alabama’s Tony Brown, who was victimized on six of Renfrow’s 10 receptions in last year’s title game, including both of his touchdown catches in the second half. Brown was the guy posterized forever on the game-winning catch in the front corner of the end zone with one second to go, after reportedly talking trash all night.

Credit: Bart Boatwright/The Greenville News via USA TODAY Sports

And although he’s played a less prominent role in the secondary this year — Brown has just one start, against Mercer, after starting nine games in 2016 — there’s a good chance he’ll be the guy matched up on Renfrow again, replacing Minkah Fitzpatrick in the nickel in the event Fitzpatrick shifts to strong safety in place of injured starter Hootie Jones. (An alternative alignment could see Fitzpatrick remain in the nickel with little-used sophomore Deionte Thompson making his first career start in Jones’ spot; but then, Renfrow has experience leaving Fitzpatrick in the dust, too.) Whoever draws the assignment, underestimating him definitely will not be an issue.

WHEN ALABAMA HAS THE BALL …

Watching Alabama’s offense miscommunicate and melt down as the walls closed in against Auburn was a surreal experience, unlike anything we’ve seen from Bama in the past decade even in defeat. And coming from this team, specifically, it was jarringly out of character. Entering the Iron Bowl, the first-string offense had committed a grand total of two turnovers all season, both coming in a blowout win at Arkansas; otherwise the starters seemed impervious to the big mistake, and most of the smaller ones. By the end of the biggest game of the season, suddenly they were struggling just to execute a clean snap.

It’s been a long time since Alabama has looked that out of sync on a big stage, and it hasn’t escaped anyone’s attention that the flop coincided with offensive coordinator Brian Daboll seeming to forget entirely the presence of Damien Harris and Bo Scarbrough in the backfield. With the season on the line, how does one of the most imposing tailback duos in the country wind up with a mere dozen carries between them? Especially when those carries netted a little more than 8 yards a pop?

The only time the offense looked like its usual, efficient itself in the Iron Bowl was on the opening drive of the second half, when Harris and Scarbrough touched the ball on five consecutive plays — a screen pass followed by four runs — that covered 79 yards in less than two minutes and gave Bama a 14-10 lead. From that point on, they combined for four carries for 13 yards over the final four possessions, largely yielding to third-stringer Josh Jacobs as the game slipped further away and the play-calling shifted increasingly to Jalen Hurts’ arm.

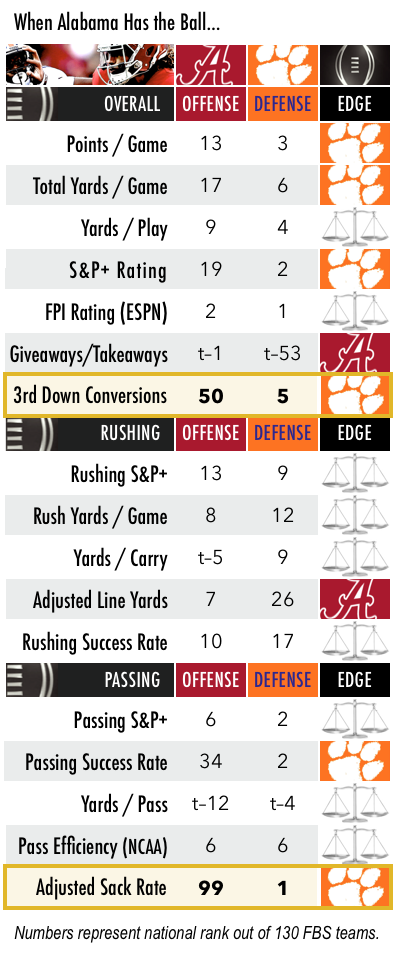

There’s a lot more to that equation than stubbornly slamming Harris and Scarbrough into the teeth of a stacked Auburn front, especially when the Tigers were equally determined to keep the ball in Hurts’ hands as often as possible. (Presumably no one in Tuscaloosa drew up a game plan that involved Hurts finishing with the same number of carries as the top three tailbacks combined.) But it’s no surprise that the emphasis over the intervening month has been decidedly of the run the dang ball variety, either. Alabama’s previous championship teams under Saban were all built on a foundation of running at will, regardless of the opponent, and personnel-wise this group is as well-suited to that mission as any of them. Despite diminishing returns in November, the Tide still led the SEC in rushing for the first time since 2011 and set Saban-era highs on the ground for both yards per game and yards per carry; in conference play, only LSU managed to hold them below 200 yards or five yards a pop. At the end of the day, this is the kind of outfit that really should be determined to run the dang ball or die trying.

There’s a lot more to that equation than stubbornly slamming Harris and Scarbrough into the teeth of a stacked Auburn front, especially when the Tigers were equally determined to keep the ball in Hurts’ hands as often as possible. (Presumably no one in Tuscaloosa drew up a game plan that involved Hurts finishing with the same number of carries as the top three tailbacks combined.) But it’s no surprise that the emphasis over the intervening month has been decidedly of the run the dang ball variety, either. Alabama’s previous championship teams under Saban were all built on a foundation of running at will, regardless of the opponent, and personnel-wise this group is as well-suited to that mission as any of them. Despite diminishing returns in November, the Tide still led the SEC in rushing for the first time since 2011 and set Saban-era highs on the ground for both yards per game and yards per carry; in conference play, only LSU managed to hold them below 200 yards or five yards a pop. At the end of the day, this is the kind of outfit that really should be determined to run the dang ball or die trying.

Because if Alabama can’t establish the run, it remains highly doubtful that Hurts’ arm is going to carry the day against a Playoff-caliber defense. It’s true that Hurts’ passing numbers have generally improved this year, largely as a result of his barely-there interception rate. (He’s thrown just one pick in 222 attempts.) In every other sense, though, his output as a sophomore reflects little to no growth: Against Power 5 defenses, his completion percentage and touchdown rate actually declined from last year, and his overall efficiency has hardly budged.

To his credit, Hurts’ fourth-quarter performance at Mississippi State was the best of his career, staving off a potential disaster in a tough environment. (Thanks in no small part to MSU’s ill-timed, badly telegraphed blitzes on the game-winning drive.) But then the disaster struck anyway, in a thoroughly pedestrian effort against Auburn that confirmed all of the lingering doubts about his ability to consistently challenge a top secondary down the field — only two of 12 completions prior to a meaningless heave on the final play traveled more than 5 yards past the line of scrimmage, a regression to the safe, horizontal passing game that he leaned on as a freshman.

In retrospect, Hurts’ arm looked like the weak link of last year’s championship run, and all the questions that followed him into the offseason continue to loom as large as ever.

Credit: John David Mercer-USA TODAY Sports

The degree of difficulty is certainly not getting any easier against Clemson, which boasts one of maybe three defensive fronts (along with Ohio State’s and Alabama’s) even more daunting than Auburn’s. To this point the Tigers’ front four is the premier position unit in college football this year, on either side of the ball, period. It was massively hyped in the preseason and has lived up to it right from the start.

Personnel-wise, the lineup is more or less an older version of the NFL-ready line Alabama faced in last year’s championship game: Three of the four starters up front — Christian Wilkins, Dexter Lawrence, and Clelin Ferrell, all returning starters from 2016 — were voted first-team All-ACC, while the fourth, DE Austin Bryant, picked up an All-America nod alongside multiple nods for Wilkins and Ferrell. All four project as potential first-rounders at the next level, following in the footsteps of the half-dozen Clemson d-linemen who have been drafted over the past three years. The top backup on the interior, junior DT Albert Huggins, likely has a pro future as well.

Production-wise, the Tigers lead the nation in total sacks, with 44, and Adjusted Sack Rate; they rank third in tackles for loss, a category in which they’ve finished no. 1 each of the past four years under defensive coordinator Brent Venables and might again if things go their way. For quarterbacks, third-and-long might as well be an invitation to start planning for a stable, profitable future in sales.

There is some hope for Alabama to pound out a decent living on the ground, where Clemson has been slightly less overwhelming (only slightly), and where Bama largely succeeded last year: The Tide were in firm control of that game before Scarbrough, the star of the first half, suffered a broken leg in the third quarter, and they finished with 221 yards rushing on 6.5 per carry. No opposing offense has come close to either of those numbers this year, in part because negative sack yards are factored into official rushing stats. But none of those offenses were Alabama’s, and anything less than that will be a bad omen for the Tide.

Key Matchup: Alabama RT Matt Womack vs. Clemson DE Austin Bryant: Womack, a redshirt sophomore, won a starting job over an influx of more hyped recruits and held it down by virtue of his strength in the running game: At 6-7, 324 pounds, he’s ideally suited to driving smaller defensive ends off the ball and engulfing linebackers on the second level. As a pass blocker, though, Womack has visibly struggled with top-shelf edge rushers, and by the end of the Iron Bowl he looked overwhelmed against Auburn’s Jeff Holland once Bama was forced into must-pass mode in the fourth quarter.

That’s an ill-fated dynamic against any member of the Tigers’ beastly front, but especially against Bryant, a next-level athlete who led the September sack parade against Auburn with four QB takedowns in that game alone.

Altogether Bryant was credited with a team-high eight QB hurries and a pair of forced fumbles to go with his 14.5 TFLs on the year, which on almost any other d-line in America would have made him the headliner. On Clemson’s, his tends to be the last name mentioned. But if this game unfolds for Alabama and Womack anything like their last one, you can expect to hear it invoked early and often.

SPECIAL TEAMS, INJURIES AND OTHER VAGARIES

Alabama should avoid at all costs putting the ball in the hands of Clemson punt returner Ray-Ray McCloud, for obvious reasons:

That was the only one he took to the house, but for the season McCloud ranked in the top 10 nationally in punt return yards and average and generally poses a threat from anywhere on the field. He’s the kind of athlete who, in addition to starting every game at wide receiver, was called on to fill in at cornerback down the stretch when the secondary began to run short on bodies. Do not kick it to that guy.

Fortunately, that shouldn’t be a problem for the Crimson Tide’s perennially underrated punter, JK Scott, who improved his hang time over the summer and turned in arguably his best season as a senior despite a decline in his overall yards-per-punt average.

Opposing returners literally didn’t have a chance: Only four of Scott’s 42 attempts were returned at all, fewest in the nation, for a grand total of 5 yards. (For comparison, Bama’s opponents returned 20 punts last year and 27 in 2015, and averaged more than 10 yards per return both years.) At the same time, only three punts went for touchbacks; the rest were either fair caught or downed, the majority of them inside the 20-yard line. Only one other FBS defense (Stanford’s) enjoyed a better average starting field position than Alabama’s, which speaks more to Scott’s value than any other number possibly could. He’ll be missed when he’s gone.

Field goals will be an adventure on both sides. Clemson’s struggles are more obvious: The Tigers lost their primary kicker, Greg Huegel, to a torn ACL in September, and beleaguered backup Alex Spence is 1-for-7 since on attempts longer than 30 yards. (At least Spence has yet to miss from 30 yards in.) But Bama has had its issues on longer kicks, too — while Alex Pappanastos remains perfect from 39 yards in, he’s just 4-of-8 from the 40-46 range, and anything beyond that is effectively out of the question. The Tide have tested Scott’s leg on a pair of 50-yard attempts, both of which he missed. Any kick in this game more difficult than a glorified extra point is a gamble.

On the injury front, Alabama’s casualties at linebacker were well-documented over the last few weeks of the regular season, beginning with injuries to Hamilton and top backup Mack Wilson against LSU; the bad news escalated last week with a foot injury that will sideline up-and-coming true freshman Dylan Moses, who started in Hamilton’s place against Auburn.

The good news at that spot (relatively speaking) is that Wilson has returned to practice and is listed as the starting Mike linebacker on the official depth chart, ahead of the much-maligned Keith Holcombe. Outside, the Tide will also be counting on significant snaps from Terrell Lewis (listed as a co-starter at Sam) and Christian Miller (a backup at Jack), neither of whom has played since going down in the season-opening win over Florida State.

With cornerback Mark Fields expected back from a foot injury, the only notable question mark for Clemson is sophomore linebacker Tre Lamar, a full-time starter who missed the past three games with a shoulder injury. Reports suggest Lamar is likely to play (he’s the listed starter at Mike), but on the off chance he’s held out again the role will fall to either James Skalski, who started the ACC Championship win over Miami, or veteran Kendall Joseph, who could shift over from Will. Otherwise the Tigers’ starting lineup on both sides of the ball has been remarkably stable all year.

BOTTOM LINE

Alabama is the betting favorite on Monday, because Alabama is always the betting favorite, but the feeling of inevitability that they carried into their past two meetings with Clemson is long gone. There’s no significant gap between these two sides athletically and no reason at all for the defending champs to feel like underdogs. Clemson beat the best teams on its schedule decisively; Alabama played one game against a team currently ranked in the AP top 15 and lost. The Tigers are coming off their best performance of the season, a 38-3 wipeout of Miami in the ACC title game; the Crimson Tide are coming off their worst. Other than the fact that Jalen Hurts has two Playoff games under his belt, there’s very little tangible difference between the quarterbacks. And Kelly Bryant hasn’t betrayed any trepidation about playing on a national stage.

It’s easy to forget just how dominant Alabama was over the first two-thirds of the season, when its two-year streak at the top of the AP poll remained unquestioned, and even easier to get too caught up in the last thing that happened. Iron Bowl flop notwithstanding, the Tide are still the no. 1 team according to Jeff Sagarin and ESPN’s Football Power Index, and no. 2 in Bill Connelly’s S&P+ ratings, where Clemson is seventh. The data knows the same thing Vegas knows: At its best, Bama is still the gold standard. After watching the fluctuations over the last month of the regular season, the only real question is whether its best is what we’re actually going to get.

SIX PREDICTIONS

1. Alabama’s defense holds Clemson to less than half of its season averages for rushing yards (204.1) and yards per carry (4.9).

2. Clemson’s pass rush forces rare turnover by Jalen Hurts.

3. Hurts finishes with fewer than 200 yards passing and converts fewer than half of his third-down attempts, but connects on a pair of timely big plays to Calvin Ridley and one of his trio of promising true freshman wideouts.

4. Both teams have promising drives negated by missed field goals.

5. After a quiet regular season, a healthy Bo Scarbrough picks up where he left off last January by handling a lion’s share of Alabama’s carries and grinding out his first 100-yard rushing game since last year’s semifinal win over Washington.

6. Alabama wins, 24–19