'I don’t feel like any progress has been made.' On the past, present and future of Black coaches in positions of power in the SEC

On a weekday summer morning, Sylvester Croom puts aside the regular chores he does around his house in Mobile, Ala. These days, his main activities consist of house projects, reading, going for walks around the neighborhood, spending time with his wife and the occasional phone call. He’s no longer consumed by the profession that he spent 40 years in, but he still watches the NFL and SEC football. Sixteen years after he became the first Black head football coach in SEC history at Mississippi State, Croom is retired.

For the better part of the next 40 minutes of a phone call, though, Croom isn’t the same relaxed 65-year-old retiree. He’s frustrated by a subject matter that he’s all too familiar with — the lack of diversity in positions of power on SEC coaching staffs.

“I don’t feel like any progress has been made, to be honest with you,” Croom says. “To think that 16 years later, it’s the fact that we’re still having this conversation.”

There are certain numbers that Croom already knows. For example, he’s well aware that including him, there have only been 5 Black head football coaches in the SEC (59 non-interim coaches have held the title of “SEC head coach” in the 21st century). Croom, Joker Phillips, James Franklin, Kevin Sumlin and Derek Mason are the 5 members of that fraternity.

“It’s pretty hard to forget anybody,” Croom says with a chuckle.

Other numbers are met with a different reaction.

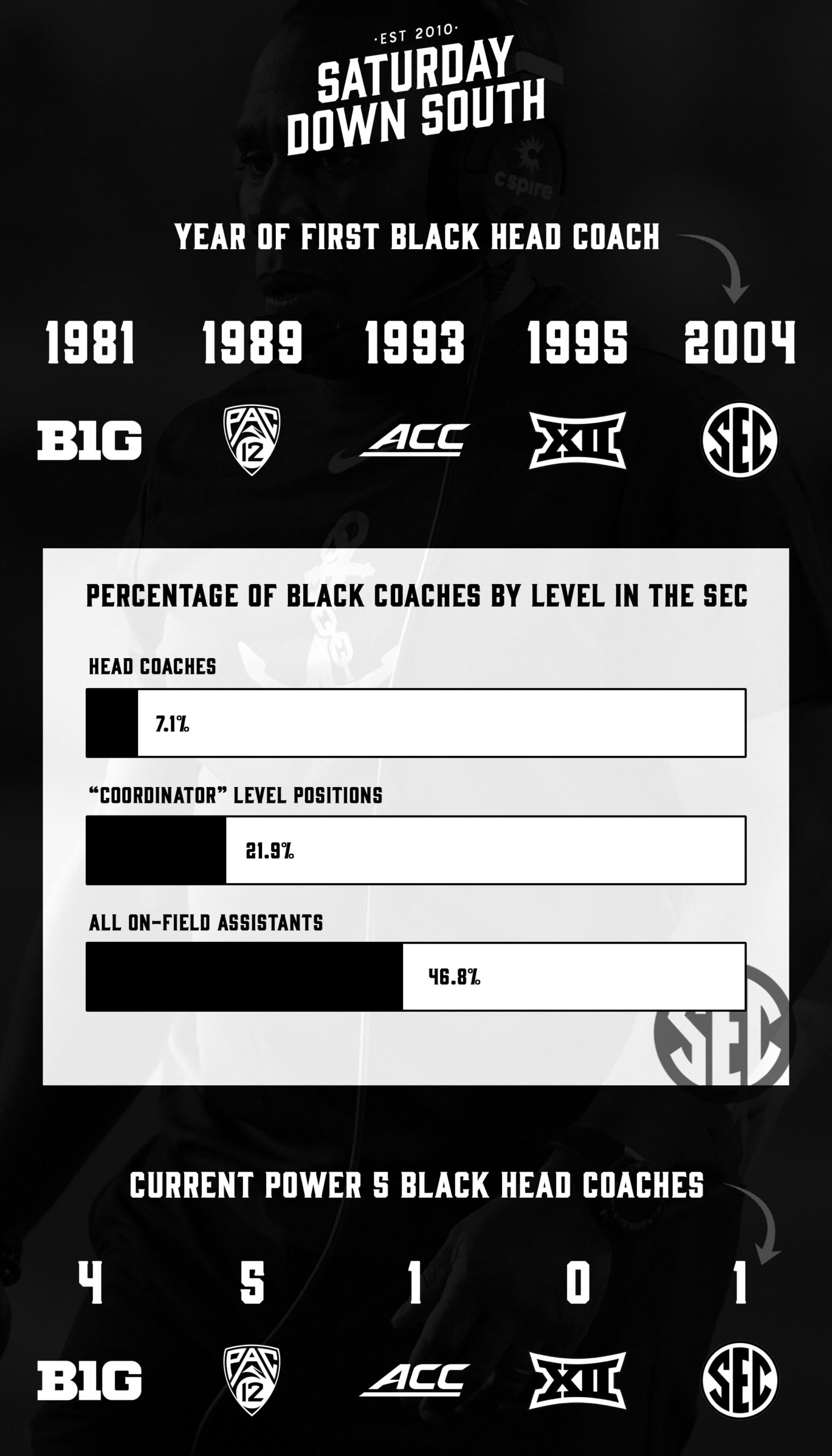

While 46.8% of the on-field SEC assistants are minorities to nearly match the 48.5% of Black FBS players (via The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport), it’s the positions of power that don’t show equal representation. In 2020:

- 1 of 14 SEC head coaches (Derek Mason) is Black (7.1%)

- 5 of the 18 SEC coaches who hold the “defensive coordinator” title are Black (27.8%)

- 2 of the 14 SEC coaches who hold the “offensive coordinator” title are Black (14.3%)

- 8 of the 46 SEC coaches who hold the title of “head coach” or “coordinator” are Black (17.4%)

Croom is asked if acknowledging that there is indeed a racial disparity in positions of power in the SEC is a fair takeaway from looking at those numbers.

“Fair? It’s absolutely accurate,” Croom says. “It’s the truth. The numbers tell you that. The numbers don’t lie. The numbers don’t lie. You’ve got almost 50% of Black coaches. Yeah, you’ve got Black coaches on your staff because you’ve got to go into those homes and recruit Black players. Not only that, but you’ve gotta have someone who can sit and talk with them once they get on campus.

“But yet, you don’t have (Black) coordinators. You don’t have (Black) head coaches. You don’t have people of authority. That’s the key thing. People of authority with power to make critical decisions. And that’s the difference.”

Croom was told those numbers before Florida’s Brian Johnson was promoted from quarterbacks coach to offensive coordinator the week of Florida’s season-opener against Ole Miss. Johnson became the first Black offensive coordinator in Florida’s history. This weekend, Johnson will face South Carolina’s Travaris Robinson, who is 1 of 5 Black defensive coordinators in the SEC. Unless Florida and Auburn face off in the SEC Championship, there won’t be any matchups with Black offensive coordinators in the SEC in 2020.

Johnson and Auburn co-offensive coordinator Kodi Burns don’t call plays, however. Dan Mullen and Chad Morris carry those responsibilities for Florida and Auburn, respectively. In other words, there aren’t any Black primary offensive play-callers in the SEC in 2020.

And of the 5 Black defensive coordinators in the SEC, 4 work on staffs with higher-up coaches who have either the role of “defensive coordinator” without any “co-” association or they work for a defensive-minded head coach. Mizzou’s Ryan Walters is the SEC’s lone Black coordinator who doesn’t have either a head coach or higher-up coach to report to on his side of the ball.

[table “” not found /]

That’s the reality 12 years after Croom made history with the first SEC staff to feature a full-time Black head football coach and 2 Black coordinators (Woody McCorvey and Charlie Harbison). That 2008 Mississippi State staff is still the only SEC program that has had that racial representation.

As Croom digs deeper into the discussion on the phone, he addresses the counterargument that he’s heard over the years about Black coaches getting opportunities in positions of power in football.

“Black people never ask for special favors,” Croom says. “We just want things to be fair.”

* * * * *

On Jan. 6, 2010, Kentucky athletic director Mitch Barnhart sat down at a press conference to the left of his newly named head coach, Joker Phillips. Barnhart never conducted a formal search to replace Rich Brooks. Instead, Barnhart named Phillips the coach in waiting in January 2008 and made good on his word 2 years later when Brooks retired. For Barnhart, the move made perfect sense. Phillips was Kentucky through and through. He grew up in Franklin (Ky.), he played receiver at Kentucky and he had 2 separate stints as an assistant at Kentucky, most recently as the offensive coordinator on Brooks’ staff.

Phillips was also the second Black head football coach in SEC history, and the first Black head football coach at Kentucky, which started playing football in 1881.

Barnhart gave an opening statement in which he referenced all of Phillips’ ties to Kentucky. There was no direct mention that Phillips followed in Croom’s footsteps, but there was a sentence from Barnhart at the opening press conference that stood out:

“Joker has been an assistant for 20-plus years, and I know there are those moments when you sit there and shake your head and wonder, ‘Will I ever get my chance?'”

A decade after Barnhart introduced Phillips, he addressed the elephant that was in the room that day.

“As a Black assistant coach, I think he was aspiring to be a head coach like many assistant coaches do, but the path was not as easy for him,” Barnhart told SDS. “There is wonder. ‘Will I ever get my opportunity? Will I ever have my chance to call a play with 40 seconds left with the game on the line as the head coach?’

“I don’t know that we talked about that specifically, but I do know that we’d be kidding ourselves if we didn’t believe that was on his mind. Frankly, it was an honor for me to be able to give him that opportunity … it felt right.”

What about the skeptics who said that Phillips was only hired to give Kentucky some positive PR for hiring the second Black head coach in SEC football history?

“I’m sure there were people who said, ‘this was just because you felt like you have to,’” Barnhart said. “I never felt that way.”

That logic ignored the fact that when Barnhart made the atypical move to name Phillips the coach-in-waiting. That decision followed a 2006 season in which Phillips, who was the offensive coordinator, helped Kentucky earn its best season in 22 years, as well as a 2007 season in which it had its best offensive year in program history. That 2007 season also saw Kentucky crack the top 10 in the Associated Press Top 25 for the first time in 30 years. That season famously included a triple-overtime win against eventual-national champion LSU, which was the program’s first win vs. the AP No. 1 since 1964.

At the introductory press conference, Phillips spoke of the goal he had in 1988 of wanting to show not only that could Kentucky be a winning program, but also that Black coaches could have success at Kentucky. Three minutes into his opening statement, Phillips paused to collect himself. He unsuccessfully fought back tears when he addressed how grateful he was that Brooks not only promoted him from receivers coach/recruiting coordinator to offensive coordinator (17 years after his coaching career began), but that he prepared Phillips to become a head coach. Understanding that the reality was truly sinking in for Phillips, Barnhart gave him an encouraging pat on the back to continue.

Brooks and Barnhart were in positions to open doors for Phillips, and even though his tenure as head coach only lasted 3 seasons, it still built on what Croom started.

But it didn’t exactly become a trend in the decade that followed.

* * * * *

The 2012 season was the first and only time there were 3 Black head coaches in the SEC. Phillips (Kentucky), Kevin Sumlin (Texas A&M) and James Franklin (Vanderbilt) made up 21.4% of the league’s head coaches. According to the NCAA Demographics Database, the 2012 season featured a total of 17 Black head coaches at the FBS level. In 2020, that number dropped to 14 Black head coaches at the FBS level. That’s 10.8%, which is slightly more than the SEC’s 7.1% representation of Black head coaches.

The disparity isn’t in the population demographics. Blacks represent roughly 13% of the U.S. population. That aligns, but in a sport with 48.5% Black players at the FBS level, the split for FBS head coaches is 10.8% Black compared to 86.2% white.

The narrowing of the gap that the 2012 season suggested isn’t quite as evident 8 years later. That year was the last time that Gene Chizik was a head coach at the FBS level. The former Auburn coach and current SEC Network analyst keeps up with the coaching trends in the conference as much as anyone. Still, the lack of Black coaches of position in the power in the SEC was noteworthy to him.

“The numbers are eye-popping for sure,” he told SDS.

When Chizik was the head coach at Auburn from 2009-12, he had an approach to making sure he had the right representation of qualified minority coaches on his staff. In addition to seeking youth, he knew that roughly 65-75% of his players were Black, and he wanted that reflected on his staff.

One of the Black players on Chizik’s team was Kodi Burns. It was Burns who famously switched from quarterback to receiver — and caught a touchdown pass in the BCS National Championship — with Cam Newton entrenched as the team’s starter. “I’ll never forget thinking, ‘A guy like (Burns) would really end up being a great coach one day,’” Chizik said. After Burns graduated from Auburn, he went over Chizik’s house to discuss the next move in his career. It was a different type of conversation than the emotional one that Chizik had with Burns when he changed positions. Chizik made it clear — Burns would be suited well to begin his coaching career.

In 2012, Chizik’s former offensive coordinator, Gus Malzahn, was the head coach at Arkansas State. Malzahn brought Burns on as a graduate assistant that year, and did so again when Malzahn took over for Chizik at Auburn in 2013. After 1-year stints as a position coach at Samford and Middle Tennessee, Burns returned to Malzahn’s staff at Auburn in 2016 as the co-offensive coordinator/receivers coach. Now, Burns is in Year 5 in that role working Chad Morris, who’s his 4th different offensive coordinator.

“He’s grown. He’s had a real open mind,” Malzahn said of Burns, who like the Auburn coach, is also from Fort Smith (Ark.) and actually played against Malzahn when he was the head coach at Springdale High School (Ark.). “He understands defenses. If something were to happen to Chad (Morris), he’d be ready to call the plays. I’ve got a lot of confidence in him … he’s a guy that’s gonna have a chance to become a head coach.”

Chizik agreed with Malzahn that the 31-year-old Burns has “future FBS head coach” written all over him. He’s already on a different path than the one Mason took. When Mason was 31, he was the defensive backs coach at Division I-AA Bucknell. It took him another 10 years to become a Power 5 position coach and another 14 years to become a Power 5 head coach. Mason acknowledged that in 2020, there’s still an uneven representation of Black coaches in positions of power in the SEC, but he’s optimistic about the future.

“There’s a lot of smart, intelligent, young coaches of color that are coming up who will have opportunities, but sometimes, you’ve just gotta wait your turn,” he said. “The opportunity is gonna come. A lot of guys are waiting in training right now. They’re looking forward to their opportunities. The SEC is probably gonna see an influx sometime in the next 5-6 years of guys who do have opportunities.”

Perhaps that could be someone like Kentucky quarterback Terry Wilson. The Wildcats signal-caller expressed a desire to get into coaching when his college career ends. Black quarterbacks like Wilson, Burns and Johnson could help change the disparity, at least as it relates to offensive play-callers (Jimbo Fisher and Lane Kiffin are actually the only former quarterbacks who are head coaches in the SEC).

So what’s going to balance out the numbers? And what active steps are being taken?

* * * * *

When Croom was an assistant in the NFL, he started attending Bill Walsh’s NFL Minority Coaching Fellowship, which began in 1987. It’s open to college and NFL coaches. The advisory board, made up of club presidents, general managers, head coaches and assistant coaches, focuses on developing a pipeline of minority coaches. It allows young minority coaches to attend NFL training camps, network and become educated on what it takes to become an NFL head coach.

The NCAA hosts its Champion Forum, which is designed to prepare coaches for the interview process. This summer, Maryland coach Mike Locksley started the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches. It’s a nonprofit organization that emphasizes not just getting into the coaching business but also rising to positions of power.

“I can only speak from my experiences, that it’s just about opportunities, it’s about awareness,” Locksley told ESPN. “You look at the three pillars of our organization: prepare, promote and produce. When you think of preparation, you think of having the tools, and this organization needs to create programming to provide tools for a youth league coach who wants to be a high school coach. … This organization has to provide the tools to help people make these jumps in their career.

“The promote piece is the part that I think has been missing. If you want to create change, there’s got to be some promotion of what’s out there.”

“Awareness” and “promotion” don’t always coincide. While every SEC team has between 3-7 Black coaches among its on-field staff, the interview process in college doesn’t have some sort of Rooney Rule, which requires at least 1 minority candidate to be interviewed for an NFL head coaching position.

Still, Croom said there should never be a shortage of minority candidates who at least interview, “and if they don’t have a list of guys who they think are good enough, tell them to call me. I know a bunch of them.” Before Croom got hired at MSU, he used to call up coaches and interview them without them even knowing that they were being interviewed. By the time he got to Starkville, he had a 10-deep list of candidates for each on-field assistant role. Croom said it would help if all assistants thought of themselves as head coaches and athletic directors.

What head coaches and athletic directors can do to help in that process, according to Mason, is actively resist putting coaches in boxes.

“We’ve got to move from young coaches who are just about recruiting and excavating talent to really diving hard into the Xs and Os and being extremely proficient so we don’t get labeled or tagged as just being one thing,” he said. “I came from a different time. The opportunities weren’t abundant, but you had to be a lot of different things. Recruiting was just a sidebar. I know recruiting is big. You still have to have Xs and Os proficiency. You have to understand everything else that comes along with the job nowadays.

“I think with that, a lot of programs are actually doing a better job of putting those young (minority) coaches to actually be in position to be trained the right way and learn more Xs and Os, whether it’s at the NFL level, the college level or at the high school ranks.”

Mason said it’s still “about right fit, right place, right time, right system.” While Barnhart echoed Mason’s sentiment that slotting coaches limits promotion, the Kentucky athletic director had a different assessment on why the disparity of Black SEC coaches in positions of power exists.

“There are things that we have got to make some progress in, giving Blacks the opportunities to be coordinators. I think that will lead to more opportunities as a head coach,” Barnhart said. “I don’t know that the answer is timing. That’s not an answer that works.

“We’ve got to be better.”

As Chizik and Croom both said, though, there’s a fine line.

When they were SEC head coaches, they actively sought the most qualified candidates above all else. There’s a difference between striving for equality and hiring a lesser candidate because of their race.

“I would say that we’re definitely heading in the right direction because it’s now highlighted more than ever that African-American coaches need to have opportunities. And that doesn’t mean you need to hand them or give them jobs because of the color of their skin,” Chizik said. “It means they need more opportunities to prove they’re qualified and if people are willing to have an open mind and do that, you’ll find that there are an incredible number of talented, great African-American coaches that more than fit the bill.

“I think it’s going to be changing for the better.”

* * * * *

Phillips always gave credit to Brooks for opening the door for him to become an SEC head coach. For Croom, that guy was Bobby Ross.

At the end of the 1992 NFL season, Ross brought Croom into his office for his year-end evaluation. It was Croom’s first year as the running backs coach on Ross’ staff with the San Diego Chargers. Croom spent the 4 previous seasons in the same role with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and he was a linebackers coach at Alabama for a decade-plus, half of which was spent working under his former coach, Paul “Bear” Bryant.

Ross told Croom some basic things, many of which he had heard before in similar year-end meetings. After all, Croom was 17 years into his coaching career. But there was one thing Ross told Croom that he had never heard before: Ross thought Croom could become a coordinator.

“I said, ‘This white man is blowing smoke up my butt,’” Croom said. “Because he was never gonna give me a chance. That’s what I thought.”

After the 1996 season, Ross was fired by the Chargers. Croom spent all 5 years as the Chargers running backs coach. Upon hearing that Ross had accepted the head coaching job with the Lions, Croom assumed he’d coach the running backs with Detroit. Following that meeting following the 1992 season, they didn’t revisit the conversation about Croom becoming a coordinator in San Diego. Ralph Friedgen got that promotion after the 1993 season and he held that title with the Chargers from 1994-96.

At the 1997 Senior Bowl in Mobile, Ross called Croom to come to his hotel room. The new Lions coach had some important news to share — Friedgen wasn’t following Ross to Detroit because he accepted the Georgia Tech offensive coordinator position.

Ross wanted Croom to be his offensive coordinator.

“I almost died,” Croom said. “He started talking about what we were gonna do, but I literally didn’t hear another word he said for an hour.”

Without Ross hiring him as an NFL offensive coordinator, Croom said he never would have gotten the call to take over at MSU. It took Croom 28 years as an assistant to get his first FBS head coaching gig. Phillips needed 22 years, while Chizik took 21 years, which is the same amount of time that Malzahn spent working his way through the high school/college ranks before getting his first FBS head coaching job at Arkansas State. Mason was 20 years into his coaching career when he accepted the job at Vanderbilt.

It takes time for coaches of all races to rise to that level. Some get there, some don’t. Sometimes it’s performance-based, sometimes it’s just bad luck.

When Croom got the job at MSU in 2004, he hired McCorvey to be his offensive coordinator. From 1990-95, McCorvey worked on Gene Stallings’ Alabama staff as the receivers coach. In 1996, McCorvey got promoted to the offensive coordinator role and helped Alabama to a 10-win season and an SEC West title.

But when Stallings retired at the end of the 1996 season, defensive coordinator Mike DuBose was promoted to head coach, and he hired Bruce Arians as his new offensive coordinator. McCorvey stayed on staff, but he didn’t run the offense anymore. He left Alabama after the 1997 season and spent 1 year as the receivers coach at South Carolina in 1998 before he came a key part of Phillip Fulmer’s staff as Tennessee’s running backs coach from 1999-2003. Two decades of experience along with his success in Knoxville and his longstanding relationship with Croom made McCorvey an obvious hire to be his offensive coordinator at MSU.

“(McCorvey) knew the SEC, he’d been at big-time programs, he’d been a coordinator at Alabama and the guy is just … he should’ve been a head coach himself,” Croom said.

After Croom was fired in 2008, McCorvey never got any closer to becoming a head coach. Croom went back to being an NFL running backs coach to finish his career before retiring in 2018.

When they were part of the first SEC coaching staff with a Black head coach and 2 Black coordinators in 2008, it was 18 years removed from John Mitchell becoming the first Black coordinator in SEC history at LSU in 1990. In 2021, it’ll mark the 50-year anniversary of when Mitchell became the first Black player ever at Alabama. He and Croom both played together on the 1972 Alabama team. Both were captains their senior seasons, and both went on to break the color barrier in positions of power in the SEC.

Croom is now far enough removed from his time at MSU to have a different perspective. He’s no longer entrenched in the on-field decisions needed to build a winning program. Croom admitted there’s some lingering regret that he often took that route at MSU instead of addressing the subject racial representation among SEC coaches.

“I didn’t acknowledge it at the time because I had a job to do, but I often think about all the things I didn’t say and all the mistakes I made sure I didn’t make so that I would never do anything to have a negative effect on the next Black candidate for a head coaching job, and it still hasn’t changed,” Croom said. “It disappoints me, to be honest with you. I felt a tremendous amount of pressure not to say the wrong thing.

“Quite often, I put my pride aside and I put my feelings aside so that I wouldn’t look like the angry Black coach.”

Croom isn’t “the angry Black coach.” He’s the 65-year old retiree who is mindful of the past, frustrated by the present and skeptical about the future of Black football coaches in positions of power in the SEC.

What Croom wants is simple; he wants to not have to pick up his phone and have the same conversation 10 years from now.