First Look: The least SEC fans should know about Clemson, a different animal the third time around

The Playoff field is set, and the first order of business for SEC fans is to get up to speed on the opposition. Click here for our primer on Oklahoma, Georgia’s semifinal opponent in the Rose Bowl. Today we turn our attention to Alabama’s all-too-familiar nemesis in the Sugar Bowl: Clemson.

1. The defensive line is elite. In fact, I’d go a step beyond elite: Collectively, Clemson’s d-line is the dominant unit in college football this season. It was hyped in the preseason, set the tone in the Tigers’ Week 2 annihilation of Auburn, and spent the rest of the year seeing it through.

Personnel-wise, the lineup is essentially an older version of the NFL-ready line Alabama faced in last year’s championship game. Three of the four starters up front — Christian Wilkins, Dexter Lawrence and Clelin Ferrell (all returning starters from 2016) — were voted first-team All-ACC by a panel of coaches and media and have a good shot at landing on some forthcoming All-America teams. (Ferrell should be a lock.) The fourth, junior DE Austin Bryant, was a second-team all-conference pick, only because there wasn’t any room left on the first. All four project as potential first-rounders at the next level, following in the footsteps of the half-dozen Clemson d-linemen who have been drafted over the past three years. The top backup on the interior, junior DT Albert Huggins, likely has a pro future as well.

Production-wise, the Tigers lead the nation in both total sacks, with 44, and Adjusted Sack Rate; they rank third in tackles for loss, a category in which they’ve finished No. 1 nationally each of the past four years under defensive coordinator Brent Venables. Third-and-long against this bunch may as well be an invitation to pack it in and start regrouping for the next series.

11/11/17 – Clemson pass rush (Clelin Ferrell, Christian Wilkins) vs. Florida State pic.twitter.com/lW95493T0j

— College Football Clips (@CFB_Clips) December 6, 2017

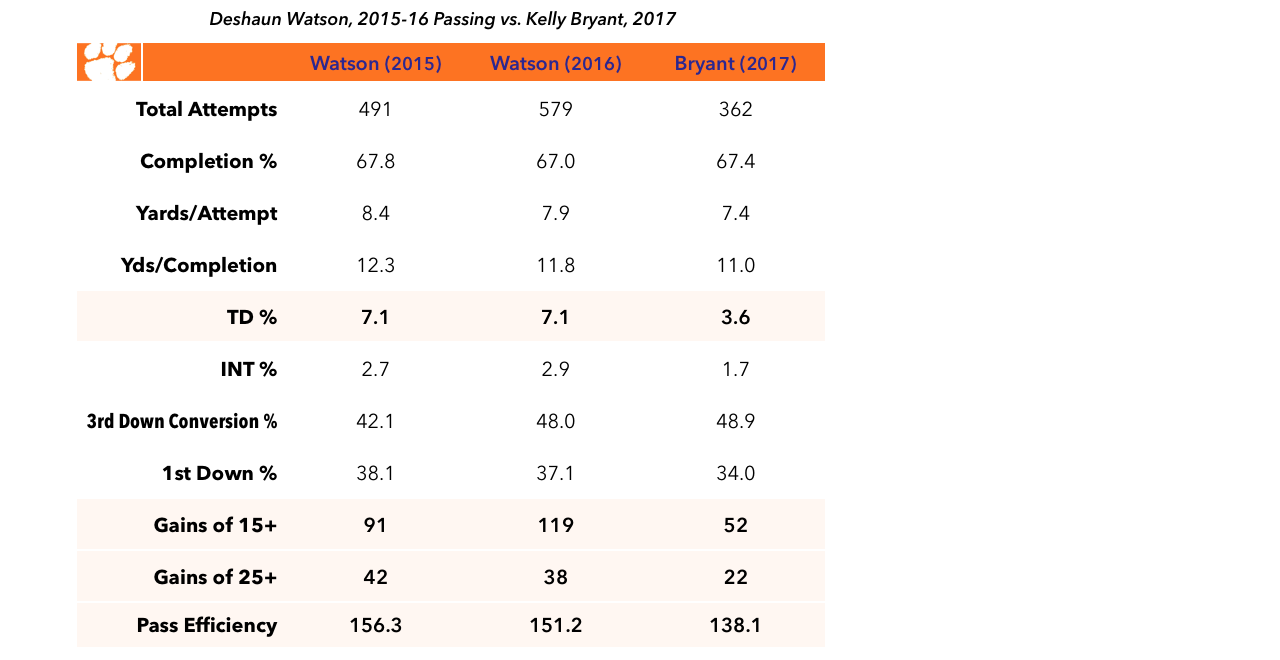

2. Kelly Bryant isn’t Deshaun Watson… Clemson is attempting to become the first team in more than 40 years to repeat as national champion after losing its starting quarterback*, and when the QB in question is the most decorated player in school history, some level of drop-off is inevitable. To his credit, Bryant is completing his passes at roughly the same rate as Watson in 2016, with a better interception rate. But he’s attempted significantly fewer of them, for fewer yards per attempt, and through 13 games has thrown for just 13 touchdowns. Through 13 games last year, Watson had thrown for 37. (*The last team to do it: Alabama in 1979, when Steadman Shealy replaced ’78 starter Jeff Rutledge.)

The upshot, predictably, is that while the offense as a whole has continued to hold up its end of the bargain — offensive coordinator Tony Elliott just won the Frank Broyles Award as the nation’s top assistant coach — on the whole it’s been more conservative in terms of tempo and play-calling and much less reliant on the quarterback to keep the wheels turning: Bryant has accounted for just 57 percent of the Tigers’ total offense this season, compared to Watson’s 69 percent last year and 67 percent in 2015. And despite the usual array of big-play targets on hand, the passing game has been far less explosive.

3. …but he might be close enough. All of that said, it’s telling that Clemson’s only loss, an otherwise random, 27-24 flop at Syracuse on a Friday night, came in a game in which Bryant was injured in the first half and didn’t play at all in the second; in his absence the Tigers managed just 10 points against the ACC’s most generous defense. Even more so than in the transition from Watson, watching the offense attempt to function even briefly without Bryant at the controls may be the best evidence yet of his value.

In the running game, for example, Bryant has been every bit the equal of his predecessor, carrying slightly more often than Watson did in 2016 for slightly more yards per carry. But his impact on the ground has arguably been greater: Where Watson was clearly the No. 2 rushing option behind All-ACC RB Wayne Gallman, the absence of an every-down workhorse this season has left Bryant to serve as the focal point — excluding sacks, he’s logged more carries for more yards than either of the Tigers’ top tailbacks, Travis Etienne and Tavien Feaster. Like Watson (and like Tajh Boyd before him), in short-yardage and goal-to-go situations Bryant often serves as a de facto tailback.

More importantly, with 12 wins under his belt in 13 starts, Bryant has outgrown the “first-year starter” phase and enters the postseason firmly entrenched. As far as Alabama is concerned, the fact that he’s coming off his best game as a passer in Clemson’s 38-3 thumping of Miami in the ACC Championship probably means less than his inconsistency over the preceding weeks. Taken with his above-the-fold performances in September wins over Louisville and Virginia Tech, though — both national TV games against opponents ranked in the Top 15 at the time — at minimum there shouldn’t be any doubts about Bryant’s capacity for rising to the occasion on a big stage.

4. Yes, Hunter Renfrow is still around. Renfrow, memorably, is the baby-faced, 5’10” former walk-on who caught the championship-clinching touchdown against Alabama last year, his second TD of that game and fourth against the Crimson Tide over two years. In that context, he’s one of the most unlikely big-game heroes in college football history. Much more quietly, though, he’s also emerged this year as one of the most reliable, efficient receivers in the country.

Those are generic “possession receiver” adjectives, but in Renfrow’s case that praise is quantifiable in a couple ways. The more straightforward measure is Catch Rate: Renfrow has 55 catches this season on 69 targets, good for a Catch Rate of 79.7 percent, best in the ACC among wide receivers who have been targeted at least 40 times. The other method is Success Rate, defined by Football Outsiders as plays that gain 50 percent of necessary yardage to move the sticks on first down, 70 percent on second down, and 100 percent on third and fourth down. Again, despite his relative lack of deep speed, Renfrow’s Success Rate (60.9 percent) is the ACC’s best among receivers with at least 40 targets.

Translation: On short and intermediate routes, the kid is a machine. Arguably no receiver in college football this year has been better at the subtleties of getting open from the slot, and on an offense that has yet to identify a true, go-to deep threat in the Mike Williams mold — Williams’ presence on the outside may be more sorely missed than Watson’s — Renfrow’s consistency in the underneath role has been that much more valuable.