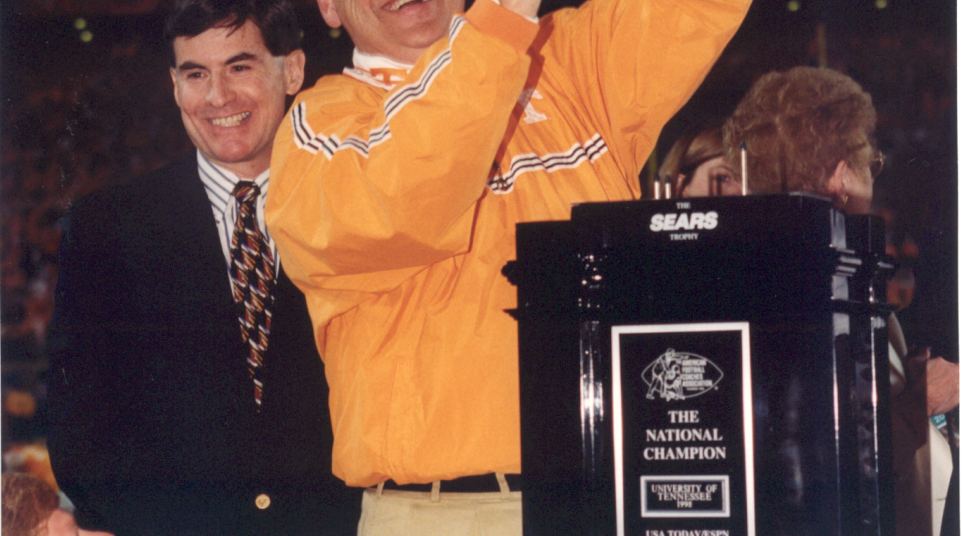

David Leaverton recalls his best tackle, the one that helped Tennessee win a national championship

Editor’s note: Welcome to Tennessee Week. Our special series — “Undefeated. Unexpected. Unforgettable.” — celebrates the 20th anniversary of the Vols’ 1998 national championship season.

“To be a part of one of the key plays … I’ll make sure I remind my friends at the 20-year reunion that they’re wearing a ring because I stopped Peter Warrick.”

You probably remember Dwayne Goodrich’s 54-yard interception return for a touchdown in the Fiesta Bowl. Surely, Tee Martin’s 79-yard touchdown pass to Peerless Price is emblazoned in your mind. However, there is one play you might have forgotten and it might have been just as vital to securing Tennessee’s first national title in 47 years. Former Tennessee punter David Leaverton hasn’t forgotten it.

With 6:07 left in the second quarter, the Vols lined up at their own 31-yard line to punt on 4th-and-22 as they held onto a tenuous 14-6 lead. Leaverton thought he had dodged a bullet when Florida State’s Reggie Burden lined up to return a punt instead of superstar Peter Warrick, who was getting a break after playing receiver on the previous series. Then an offsides penalty changed everything. After the short break, Warrick took Burden’s place.

“I was like, ‘Ah crap,’” Leaverton said.

With adrenaline flowing, Leaverton outkicked his coverage. It looked as if Warrick would make him pay. Warrick weaved through UT’s usually solid punt coverage team in the middle of the field. That meant Leaverton had no sideline to help him. Warrick even had a blocker ahead.

For some reason, perhaps disrespecting a punter, the blocker ran past Leaverton. There was one man between Warrick and the end zone: Leaverton.

“I just kind of ran at him and lowered the boom and, by God, I got him,” Leaverton said. “I was kind of surprised. I think if we did it 10 more times, he would have scored 10 more times. It mattered when I got him.”

The momentum swing that Warrick’s punt return could have caused had been avoided. The Vols would hold on to beat Florida State 23-16.

“To be a part of one of the key plays … I’ll make sure I remind my friends at the 20-year reunion that they’re wearing a ring because I stopped Peter Warrick,” Leaverton joked. “There were other people involved in the game, I know, but I won’t diminish my importance. Twenty years later it gets even greater.”

After his UT career was complete, Leaverton was selected by the Jacksonville Jaguars in the fifth round of the 2001 NFL Draft. Leaverton never could quite stick with an NFL team as he bounced from the Jaguars, to the Jets, Patriots, Redskins, Rams and Buccaneers.

“I spent more time in what I would call ‘in between teams’ as opposed to on teams, which is a nice way of saying unemployed,” Leaverton said.

Leaverton kept punting back in Knoxville, hoping for another shot at the NFL. At some point, he decided that practicing his craft didn’t completely fill his days. So instead of playing video games, he decided to volunteer for a political campaign. He chose to support Lamar Alexander’s bid to become a United States Senator. There was a Tennessee connection that helped Leaverton climb the ladder quickly. Alexander was formerly the President of the University of Tennessee.

Leaverton’s future seemed set. He had great connections at an early age. He was handsome, affable and well spoken. He seemed destined to be a lifelong politician. There was just one problem. When he got to Washington, D.C., and worked in various roles, he saw an underbelly of government that made him uneasy.

“Really through that process, I began to see the dysfunctional nature of our federal government,” Leaverton said. “It was really discouraging for me because I went into it bright eyed and optimistic.”

Leaverton managed to stomach the political realm for six years before deciding it was time to go. He returned to Texas to enter the private sector and start a family. Then, the 2016 campaign unfolded. Leaverton had that uneasy feeling again.

“It was so visceral and so ugly,” Leaverton recalled. “I just saw our country devolving in such a horrible position, I said, ‘I want to do something about it. What I’m seeing before my eyes is heartbreaking. I’m seeing Americans attack each other in the streets.'”

That’s when Leaverton made a drastic decision.

Family photo courtesy of David Leaverton

Leaverton and his wife sold their house, quit their jobs and decided to tour all 50 states in a recreational vehicle with their three children, who were 7, 5, and 3. With 420 square feet, calling it cramped would be an understatement. Leaverton’s goal was to gain perspective from learning about the perspective of others.

Leaverton and his wife started a non-profit organization called Undivided Nation. The focus was on reconciliation and unity.

“We had no clue what was dividing people so we had to get outside our bubble,” Leaverton said.

Leaverton isn’t trying to raise awareness on the issue of divisiveness just yet. He said he’s trying to listen and learn before he shares whatever message he decides needs to be delivered.

“Before you speak, you need to listen,” Leaverton said. “That’s really what this year is for us, to listen and to learn. I think the worst thing is to go out and act like you’ve got all of the ideas, so we don’t really have a lot of ideas, but we’ve been transformed by what we’ve learned and what we’ve seen. There are people across our country whose lives are so different than our own. Their experiences are different. We’ve uncovered a history that we didn’t know existed.”

Leaverton has covered 31 states halfway through his year-long journey. From town to town, he visits with people about their view of America. One of the most profound conversations occurred when he reached out to an 85-year-old African American man in Savannah, Ga. The spoke for a few minutes before the tone changed.

“The only white people around here in Savannah who will even talk to me are guilty liberals,” Leaverton recalled the man saying. “I thought that was interesting. He said ‘Even if I had time to talk to you David, I don’t think I would. It’s hard to be reconciled with someone that has a boot on your neck.’”

That conversation made Leaverton feel insensitive. Leaverton realized America needed to address why some people feel oppressed before it’s time to discuss reconciliation and unity.

Leaverton blames social media as part of the problem. While we’re connected, each person’s message is tailor made for each individual, not the entire population.

“My social media feed, because of these algorithms, tell me exactly what I want to hear,” Leaverton said. “They tickle my ears. People in my neighborhood often look and think and act allot like I do. The media sources that I consume are things that tell me what I already believe and confirm those things. We rarely get a chance to see life through someone else’s eyes and see their perspective. I know my perspective. I don’t need anymore of that. I’ve got that pretty well.”

Leaverton said he doesn’t plan to reenter politics after his journey, saying that would feel “futile.” He said he hopes to educate Americans about the humanity that exists even in their enemies.

“What I’m going to do with this after this year, I’ve got no clue,” Leaverton said. “We’ll be homeless and unemployed, but we’ve got a really nice RV and we can settle down wherever we want to. I really don’t know that the future holds.”

The future will surely hold one thing for Leaverton, tales of his favorite play as a Vol.

“To this day, this punter that you’re talking to is not known for punting but for tackling and that’s fine,” Leaverton said.

Leaverton even found an opportunity to tell his favorite story during his recent tour. It took place when he met a couple in Alaska. The man was wearing a Florida State hat. The woman had donned a Tennessee cap.

“I went in and told them that I was involved in making his day sad and her day happy,” Leaverton said of that memorable day in Jan. 4, 1999.

The Vols will celebrate the 20th anniversary of the 1998 National Championship team during the weekend of the Florida game. Among the throng of RV’s housing fans to see the game, one will be manned by a tackling machine.

NEXT: Where are the 1998 Vols now?

Cover photo courtesy of University of Tennessee Athletics.