The Scott Frost File: Catching up with the heir apparent at Florida (or Nebraska, or Tennessee, or ...)

It’s November already, which for college football fans means the same thing every year: The days get shorter, Playoff speculation ramps up in earnest, and hot seats begin to boil over. After a couple cycles of relative calm, the SEC is set for an unusually turbulent go of it this time around, the first shot of which was fired last weekend when Florida abruptly announced it was parting ways with coach Jim McElwain.

At least half the conference is in for some degree of intrigue. Barring a miracle over the coming weeks, Butch Jones and Bret Bielema are on deck, and neither Kevin Sumlin nor Gus Malzahn is necessarily in the clear. (The loser of Saturday’s Auburn-Texas A&M game will be in for a rough few weeks — especially if it’s Malzahn, whose team still has to play Georgia and Alabama.) The looming vacancy at Ole Miss is still plagued by the threat of NCAA sanctions; with the Florida job in play, Mississippi State fans are back to holding vigil over Dan Mullen’s future in Starkville.

In most of those cases, the fate of the head coach is the only suspense left in a season whose possibilities are otherwise exhausted, and the stage is set for a stock character in our little drama: The Up-and-Comer. He’s young, fresh, a winner — what he lacks in experience, he makes up for in attitude and wild, seemingly overnight success at the helm of a traditional backwater. He has the media’s attention and none of the baggage of older coaches who have been around the block. He has momentum. You don’t know much about him, but what you do know you like. And if your team is staring down the prospect of an imminent coaching change, you now you want him before he gets snapped up by somebody else with the same idea.

Last year, the role of the Up-and-Comer was played primarily by Houston’s Tom Herman, a former Ohio State assistant under Urban Meyer whose immediate success in the mid-major ranks set him on the course to fame and fortune at a powerhouse program in less than two years; he chose Texas over LSU, a decision that could reverberate for years, in multiple directions. (There were also cameos by Western Michigan’s P.J. Fleck, Western Kentucky’s Jeff Brohm, and South Florida’s Willie Taggart, en route to their new gigs at Minnesota, Purdue, and Oregon, respectively.)

This year, the role has been filled by Central Florida’s Scott Frost, 42, whose decision to take over a hapless, 0-12 outfit in December 2015 is about to pay off, quite literally. Two years later, the Knights are undefeated, with a pair of double-digit wins over fellow AAC contenders Memphis and Navy, and likely to finish that way, presumably in a New Year’s Six bowl. By then, the coach who oversaw their worst-to-first run will presumably be long gone.

Gone to where, exactly, is still an open question. As of this week, the betting markets have tabbed him as the odds-on favorite to replace McElwain at Florida, although that’s due in part to the fact that the opening in Gainesville happens to be the only really attractive, high-profile vacancy (sorry, Ole Miss) in the wake of the Gators’ split with McElwain. As others begin to open up — especially at Frost’s alma mater, Nebraska, where incumbent Mike Riley is hanging on by a thread — those odds could change. What’s certain is that Frost’s name will be a permanent fixture in the conversation over the next six weeks, or however long it takes for an enterprising athletic director to pony up enough to close the deal.

In the meantime, here’s everything you need to know right now about the guy who, soon enough, you may feel like you know better than you ever wanted:

1. Nothing But a Winner. If you’re over 30 (hello), your default mental image of Frost probably still involves him in a Nebraska uniform, oversized 1990s shoulder pads and all, running for huge chunks of yardage as the point man in the Cornhuskers’ legendary triple-option scheme. In his last two years in Lincoln, Frost was 24-2 as a starter, won a share of a national championship, and starred in one of the most dramatic plays in recent memory, the Flea Kicker. (He was also enough of a raw athlete to convince the New York Jets to draft him in the third round as a safety.)

His playing career arguably rivals Jim Harbaugh’s, Kliff Kingsbury’s and Pat Fitzgerald’s as the best among active head coaches; 20 years removed from his senior season in Lincoln, the rhythms of the option are embedded deeply enough in his DNA that earlier this year he decided the best way to prepare his defense for facing Navy was to put on a helmet and run the scout team offense himself.

But his record on the sideline is at least as impressive, even prior to the turnaround at UCF: In nearly a decade as a full-time college assistant, he was part of teams that won at least nine games every year from 2007-15 at both Northern Iowa (where he was linebackers coach in ’07-08) and Oregon, where he spent four years as an offensive assistant under Chip Kelly and Mark Helfrich. Altogether that run included six conference championships, back-to-back FCS playoff appearances in his two seasons at UNI, and five consecutive top-10 finishes at Oregon.

Although it was a major step forward from 0-12, last year’s 6-7 finish at Central Florida was also the first losing team Frost had been a part of in any notable capacity since his last full year in the NFL, as a backup for the 7-9 Cleveland Browns in 2001.

Former USF coach Willie Taggart and Scott Frost meet after USF beat the Knights 48-31 last season. Credit: Kim Klement-USA TODAY Sports

2. A Chip Off the Old Chip. To whatever extent he’s still identified with an outdated version of the option, at this stage in his career the most important influence on Frost’s offensive philosophy, by far, is Chip Kelly. Frost spent four years on Kelly’s Oregon staff (2009-12) as the WR coach, coinciding with the Ducks’ emergence as the dominant program on the West Coast, and although “the spread” was a well-established concept by that point, no one had pushed those concepts to such extreme limits. Kelly’s cutting-edge offense was the fastest in football and the most consistent, averaging at least 46 points per game in each of his last three seasons.

By the time Frost was promoted to offensive coordinator, in 2013, he was steeped enough in the system to help perpetuate its success even after Kelly’s departure for the NFL — post-Kelly, Oregon finished in the top five nationally in scoring offense, total offense, and yards per play each of the next three years, highlighted by a national championship appearance and a Heisman Trophy win by QB Marcus Mariota in 2014. And it wasn’t all due to Mariota: The following year, the Ducks finished with virtually identical numbers across the board behind a graduate transfer, Vernon Adams Jr., who went 7-2 as a starter in his only season on the FBS level.

From the outside, it’s hard to gauge exactly how much Frost had to do with that success in the shadow of Kelly and his successor, Helfrich, who preceded Frost as Oregon’s OC. And it would certainly be a stretch to suggest that the Ducks’ subsequent crash in 2016 was due in any tangible way to Frost’s departure for the top job in Orlando. What we can say, though, is that after a rough debut at UCF (which, again, was coming off a complete meltdown in all phases in 2015) the Knights’ offense in 2017 went from zero to vintage Oregon virtually overnight:

(Note that the last column, Offensive S&P+, is adjusted for strength of schedule.)

I included UCF’s 2015 output, preceding Frost’s arrival, to give some context of where the Knights were starting from — there were 128 FBS teams that year, putting the Knights among the bottom three in each of those four categories — and just how insanely dramatic this year’s surge has been by comparison. Through seven games, UCF has already scored more touchdowns (48) than it did in 13 games last year (46), and nearly three times as many as it scored in 2015 (18).

Going back further, the current attack is easily exceeding the output of the 2013 team, the best in UCF history to date, which finished 12-1, won the Fiesta Bowl, and sent starting QB Blake Bortles on to become the no. 3 overall pick in the draft. The offense that year averaged 34.6 ppg; this year, the Knights have eclipsed that number in every game but one.

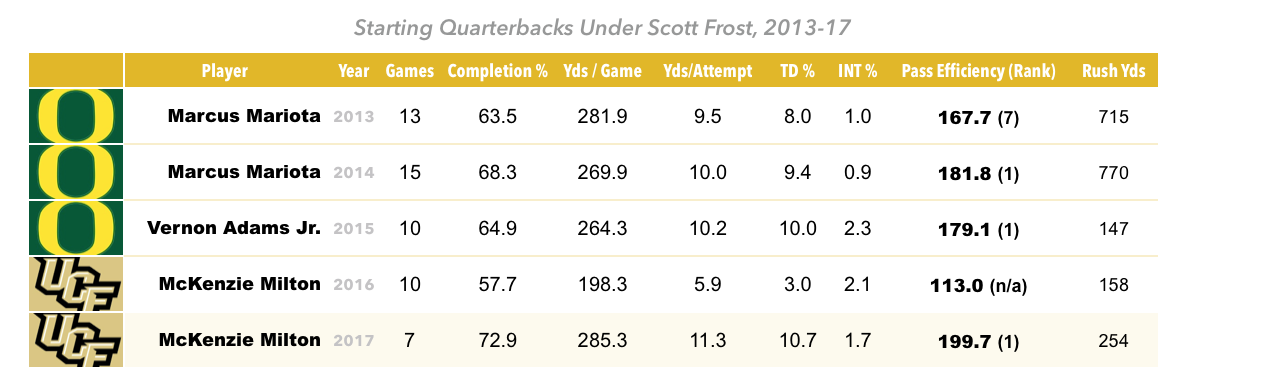

3. The Man, the Myth, the Milton. More specifically — and most encouragingly, where Florida is concerned — is Frost’s track record with quarterbacks, which has taken on an entirely new dimension this season with the ongoing development of sophomore McKenzie Milton. As a true freshman in 2016, Milton (officially listed at 5-11, 185 pounds) was good enough to take and hold down the starting job but struggled badly over the second half of the year, ultimately failing to crack the top 100 nationally in pass efficiency. As a sophomore, though, he’s been outrageously efficient, entering November as the FBS leader in completion percentage (72.9), yards per attempt (11.3), and overall passer rating (199.7).

Those numbers hardly seem sustainable, but if Milton somehow manages to maintain that pace down the stretch, that last number would break the single-season efficiency record set last year by Baker Mayfield. (At the moment, Mayfield’s 2017 rating comes in just behind Milton’s, at 195.6; the next guy on the list, Ohio State’s J.T. Barrett, is almost 20 points back.) And record or not, if he finishes no. 1 Milton will be the third different QB coached by Scott Frost to lead the nation in efficiency in the past four years:

All due respect to McKenzie Milton, who’s obviously putting together a very fine, award-worthy campaign. But any list that shows him performing in the same stratosphere as Marcus freaking Mariota says a lot more about the common link between them — their coach — than it does about their respective skill sets. Ditto Vernon Adams, for that matter, who’s a third-stringer with the CFL’s Saskatchewan Roughriders. Frost is three-for-three in developing highly productive starters, and only one of the three has possessed legitimate NFL potential.

In the same vein, although UCF doesn’t push the tempo to nearly the extent that Oregon has in the past, the Knights have managed to get an impressive percentage of the depth chart involved, generating first-rate production without the benefit of a go-to skill player or anybody who even remotely resembles one. By my count, 23 different guys have recorded multiple touches on offense this season, significantly above average, about half of whom are averaging between two and eight touches per game; no one is averaging ten. As a team, the Knights lead the AAC in total offense with only one player among the league’s top 20 in yards from scrimmage — RB Adrian Killins Jr., who comes in 19th.

That kind of everyman distribution pattern is more common to triple-option teams — even Oregon, which is fairly egalitarian in this respect, has never spread it that thin — and coming from a very modern, RPO-heavy spread philosophy it’s even more of a nightmare to defend.

4. Wait, Nebraska is probably going to fire its head coach, too. Do the Huskers have dibs? That likely depends on Frost, a born-and-bred Nebraskan, and how deeply he feels drawn back to his home state and/or alma mater. At this point, Nebraska football has been so mediocre for so long — zero conference titles since 2000, zero major bowl games or Top-10 finishes since 2001 — that it might as well paint the words “Identity Crisis” in the end zones. Résumé notwithstanding, the true allure of Frost returning to Lincoln is that his presence alone would serve as a reminder that that wasn’t always the case.

It’s the same reason he was regarded as a serious candidate for the Nebraska job three years ago, with no head-coaching experience at all: The further they recede into the distance, the more sense an overt bid to revive the glory days seems to make. Frost’s father, Larry, played football at Nebraska; his mother, a former Olympian, briefly coached the women’s track and field team. The new athletic director in Lincoln, Bill Moos, has praised Frost as “the full package,” even though Mike Riley remains on the job. “The only thing that (Frost) was missing, back then (in 2014), in my opinion, was actually being a head college coach and all the other responsibilities and obligations that come with that,” Moos told a local radio station, “and he has handled that superbly, from afar, as I look at it.”

Credit: Jim Brown-USA TODAY Sports

But a homecoming is hardly a foregone conclusion. For one thing, although Nebraska enjoys famously loyal fan support and healthy finances as part of the Big Ten, the inherent limitations to sustaining an elite program there are well-documented. There’s no natural recruiting base in the dead center of the country, and an entire generation has come and gone since the last class of players that grew up thinking of the Huskers as a relevant player nationally.

According to 247Sport’s composite rating, Nebraska hasn’t landed a top-20 signing class since 2011, its first year in the Big Ten, and the state of Nebraska itself hasn’t produced a single 4-star prospect since 2013. Nor do the Cornhuskers boast the enormous advantage they once did in player development, by virtue of being the first major program to embrace modern strength training in the 1970s.

Florida, on the other hand, remains a perennial recruiting power in the most fertile football state in the union, regardless of the coach or the results in a given year. That’s the calculation Urban Meyer made in 2004, when he notoriously spurned his dream job, Notre Dame, for what he viewed (correctly) as a more favorable situation for winning championships in Gainesville. Unlike Meyer at the time, Frost has already forged connections in Florida: His first full recruiting class at UCF was generally regarded as the best outside of the Power 5 conferences. Should it come open, Texas A&M can make many of the same arguments re: building a blue-chip roster in Texas. The “Big Three” jobs in the Big Ten — Michigan, Ohio State, and Penn State — are arguably as attractive at the moment as a top-shelf SEC gig; Nebraska, for now, is not quite in that class.

More pointedly, there’s an element of wishful thinking in the Frost-to-Nebraska narrative that trades vision for nostalgia. Frost himself has admitted that his college career didn’t go quite as smoothly as people tend to remember. And it’s not 1997: He isn’t about to bring back the I-formation, or the triple option in any recognizable form, and even if he did he’d be hard-pressed to find a Tommie Frazier or Eric Crouch (or Scott Frost) to run it. He isn’t going to bring with him a sudden influx of skill talent, or install a revolutionary strength-and-conditioning culture as far ahead of the curve as Nebraska’s was back in the day. He’d face the same challenges on the field as any other coach who accepted the job, with an entirely different set of expectations and assumptions about how he ought to be going about meeting them.

His own preference is anyone’s guess, but the fact that Frost’s past is in Nebraska doesn’t mean his future has to be. If the goal in Lincoln is to move forward, it might be for the best on both sides if he sets down roots in the Sunshine State.