Film Study: How Alabama learned to stop worrying and love the spread

“Is this what we want football to be?”

When Nick Saban asked the immortal question back in 2012, fresh off a win over Ole Miss and its spread-friendly new coach, Hugh Freeze, it was interpreted as a rebuke to hurry-up/no-huddle offenses everywhere, as if Saban barely recognized what he was seeing from opposing offenses as the same sport. At the time, Alabama was on its way to repeating as national champion, and the spread revolution stood in stark contrast to the much sturdier material the burgeoning Bama dynasty had been built on.

Four years later, though, it’s possible to read the quote in retrospect less as contempt for the direction of the sport than concession: Is this what we want football to be? It is? Well, OK then. I’m in.

Because to watch Alabama’s offense in 2016 is to get a glimpse of a full-fledged spread-option attack very much in tune with its era, the end point of an evolution that began with Lane Kiffin’s arrival as offensive coordinator, in 2014, and began to glimpse its full potential with the elevation of Jalen Hurts to starting quarterback earlier this year.

Hurts is a novelty, both as a true freshman on the No. 1 team in the nation — no true freshman QB has led his team to a national title in more than 30 years, or even come close — and as a dynamic athlete in a position that has long been defined by a lineage of indistinguishable “game managers.” But his impact has been immediate and obvious: Alabama is on pace to set school records for yards and points per game, in a scheme tailor-made for its precocious headliner’s talents.

With Hurts at the controls, an attack that lost a Heisman Trophy-winning tailback has increased its per-game output on the ground by more than 30 percent on roughly the same number of carries, mostly through big plays — through eight games, the Tide have as many runs covering 20 yards (23) and 30 yards (13) as they did last year in 15 games.

Two-thirds of the way through the regular season, whatever questions there were about the capacity of the offense to adapt to a scrambly freshman, or vice-versa, have been put to bed; the 2016 edition has looked as consistent as any offense in the Saban era, and on the ground, at least, has been considerably more explosive. As it enters the November stretch with yet another championship in its sights, the most pressing now is, can it be stopped?

Going All the Way.

To be perfectly clear: This isn’t a case of an offense sprinkling a handful of spread concepts into an otherwise traditional playbook. Even the stodgiest schemes these days dabble in the shotgun and three-receiver looks, and Alabama took that kind of half-measure approach for years, long before Kiffin came along to accelerate the process. But this is the first year they’ve taken the plunge, committing themselves from the outset to a full-time spread system.

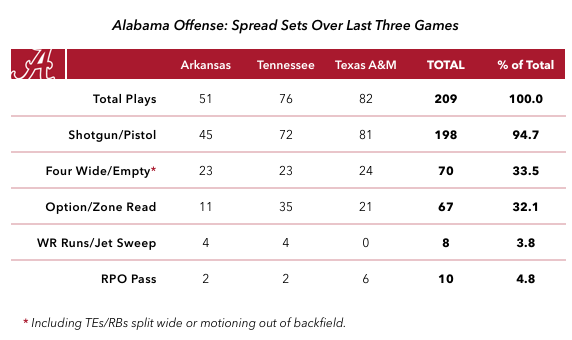

Just a few years ago, of course, Bama fans relished mocking spread offenses as foreign, gimmicky, and soft. As I pointed out the last time I wrote about Alabama’s offense, though, the kind of stuff that was once considered an exotic sideshow — no-huddle tempo, four-receiver sets, run/pass options, a constant array of pre-snap motion into and out of the backfield — is now the base offense. For a snapshot, just look at the past three games, all against conference opponents ranked (at the time) 16th or higher in the AP poll:

With few exceptions, the Tide have operated exclusively from shotgun and pistol looks, and almost exclusively with three wide receivers. About a third of the time they go four-wide (the fourth receiver is usually tight end/H-back O.J. Howard, who’s more than athletic enough to challenge opposing secondaries from the slot) or empty the backfield entirely; the zone read has emerged as such an every-down staple that they often run it several plays in a row.

On a whiteboard, this looks a lot more like what Auburn or Clemson was doing five years ago than what Alabama was doing, and if Saban remains more reluctant to push the pace than some of the more enthusiastic hurry-up/no-huddle evangelists, the fact that Alabama has embraced the “no-huddle” half of that equation means the “hurry-up” part is always an option. And Bama does a little bit of that, too.

None of which, for the record, is meant to suggest in any way that Bama is suddenly a “finesse” team. The soft/gimmicky label was always a dumb trope when it was leveled against the Oregons of the world, and in Alabama’s case it would be even more off the mark.

To the contrary: The Tide are still run-heavy — they’re keeping it on the ground a little more than 60 percent of the time, more often than any other SEC offenses except Auburn and Kentucky (!) — and the spread-to-run approach offers obvious advantages to a blue-chip lineup that figures to win the majority of one-on-one matchups. In certain ways it allows Alabama to do what it’s always done even better.

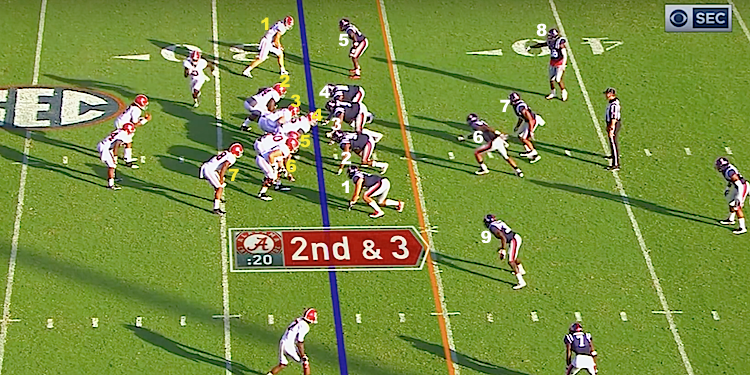

For example, take arguably the biggest play of the season: A 68-yard touchdown run by Damien Harris against Ole Miss, in early September, which put Alabama ahead for good in its most competitive win to date. (Before this run the score was tied at 27 late in the third quarter.) Beneath the window dressing, this is a tried-and-true power play, and at the snap, the numbers clearly appeared to favor Ole Miss — the Rebels were in their usual 4-2-5 personal with nine defenders in the box vs. just seven Bama blockers, theoretically giving them enough flexibility to account for both Hurts and Harris even if Alabama executes every block:

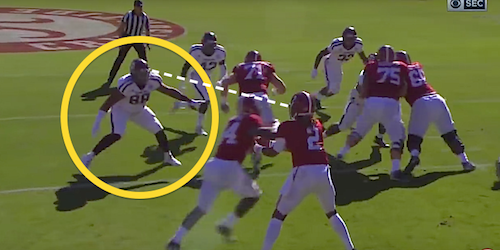

But Alabama wrecked that math in a couple ways that actually amplified its superiority in the trenches. First, there’s the pre-snap motion by wide receiver Calvin Ridley (No. 3), who had already scored a touchdown in the first half on a jet sweep; that had the effect of drawing one linebacker (Terry Caldwell, No. 21) out of the box in pursuit and holding the nickel safety to bottom of the formation (A.J. Moore, No. 30) — basically, sending Ridley in motion had the effect of “blocking” two players without laying a hand on either one.

Second, and maybe more important, is simply Hurts’ presence as a running threat at all times: Even when he has no intention of keeping the ball, as he doesn’t here, Hurts still commands enough respect with his legs to prevent the play-side defensive end (Marquis Haynes, No. 10) from crashing inside, and to force the play-side safety (Zedrick Woods, No. 36) to take an outside pursuit angle in hopes of containing Hurts if he keeps to the outside.

Meanwhile, Harris will be escorted to the line by a pair of lead blockers, Howard and right guard Alphonse Taylor, pulling from the right side of the formation to the left.

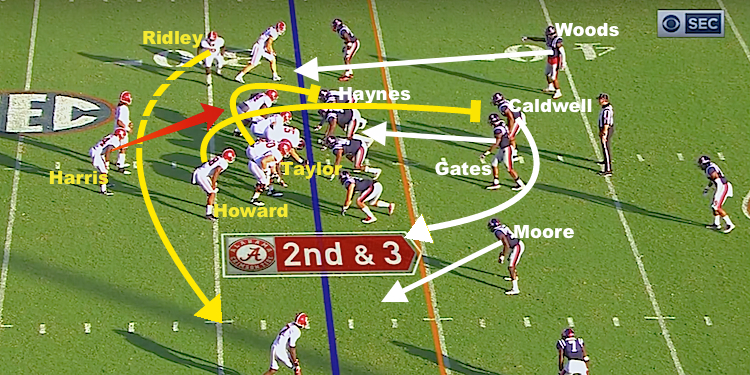

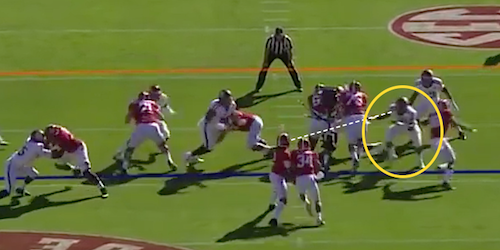

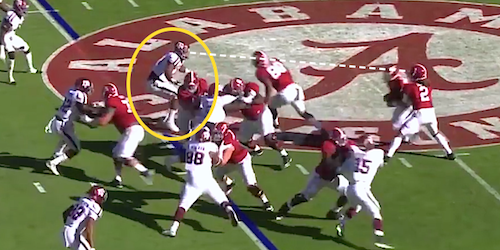

Now do the math: With Caldwell and Moore over-pursuing in one direction (in response to Ridley) and Woods over-pursuing in the other direction (to account for Hurts), that leaves seven Bama blockers for just six box defenders, an easy win for the more talented team. Here’s the hole that left Harris to run through, from the opposite end zone:

Ole Miss is so thoroughly overmatched up front here — most notably by Cam Robinson (No. 74), who delivers a devastating down block off the snap, and Taylor (No. 50), who pulls from right guard to kick out Haynes at the end of the line — that the other lead blocker, Howard, is more than 15 yards downfield before he finally encounters an unblocked defender. And by that point, Harris has already decided it’s end zone or bust.

That was back in Week 3, and if you had to point to the specific moment that Alabama fully embraced its spread-to-run identity, the second half of the Ole Miss game is the likely choice.

Hurts (146 yards) and Harris (144) both eclipsed the century mark on the ground, a rarity on Saban’s watch— for Hurts, especially, given that no previous Saban quarterback had ever come anywhere near a 100-yard rushing game — and Bama piled up more rushing yards as a team (334, including sacks) than it had posted against an SEC opponent since 2013.

It wouldn’t be accurate to suggest the ground game alone was responsible for erasing a 24-3 deficit against the Rebels on an afternoon that saw the defense and special teams score as many touchdowns (three) as the offense. But it wasn’t a coincidence that with their backs to the wall the Tide turned primarily to the spread option, or that it subsequently became the foundation on which to build the rest of the season.

By its most recent game, a 33-14 win over Texas A&M, it was possible to summarize Alabama’s down-to-down ground game in just a handful of plays, most of which ask Hurts to make a basic initial read and react accordingly.

On its first run of the day, for example, Bama opened with a midline read, on which the QB decides to keep or give the ball based on the backside defensive tackle. In this case, the tackle stays home to prevent Hurts from taking off up the gut …

… freeing up Harris for a 30-yard gain behind some outstanding, athletic tandem zone blocking by left guard Ross Piersbacher (No. 71), center Bradley Bozeman (75), and right guard Lester Cotton (66).

On the very next play, Bama went with a more familiar zone read look, with Hurts reading the play-side defensive end. In this case, the end crashes inside on Harris …

… as does the outside linebacker, for some reason, allowing Hurts to keep for a 16-yard gain behind a lead block from O.J. Howard.

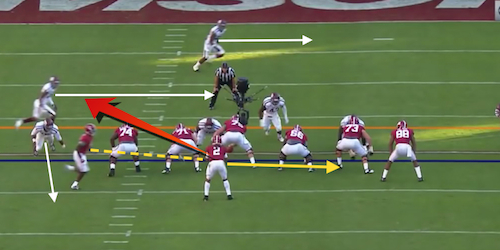

Later on in the first half, we’ll get the same play — same formation, same pre-snap motion by Howard, same read by the quarterback — except this time the unblocked end will stay at home to account for Hurts …

… opening up a lane for Harris to break off another 30-yarder behind more great blocking from Bozeman, Cotton, and especially right tackle Jonah Williams (No. 73), another true freshman who does a solid job here working off the initial double-team off the snap to pick up a linebacker (Shaan Washington, No. 33) on the second level.

And then there are plays like this one, in the third quarter, which don’t necessarily require any post-snap reads by Hurts but do further demonstrate how easily spread formations can open things up for a team with Alabama’s abundance of weapons.

Here, the Tide come out in an empty backfield (the running back, Harris, is split wide to the left of the formation; there’s trips to the right) and bring Ridley in motion from the slot. A&M is not only spread thin in the box by the formation; Harris’ lining up as a wide receiver also leads to some confusion in the secondary, and to multiple defensive backs overreacting to the threat of Ridley on the jet sweep …

… leaving no one at home to account for the possibility of Hurts simply tucking and running to the backside. Which (surprise) he does, for a 20-yard gain that put the Crimson Tide on the doorstep of a go-ahead touchdown.

That’s about as easy as 20-yard gains come in the SEC, in no small part due to Hurts’ exceptional speed, vision, elusiveness, etc. But it was made possible by Alabama’s ability and willingness to force A&M to defend the entire field, and the cracks that inevitably begin to show under the stress of trying to do so against an attack with so many options at its disposal.

It’s the Little Things.

The glaring deficiency in Hurts’ game at this early stage in his career is his consistency throwing the ball downfield: Although he certainly has the arm to challenge secondaries deep, and has connected on at least one or two long balls per game, on film even the Hurts for Heisman crowd has to concede that his pocket presence and accuracy have a ways to go before anyone starts projecting him to the next level.

That’s to be expected; it’s the main reason there was so much skepticism that a team with Alabama’s ambitions would cast its lot with such a raw prospect in the first place. There’s plenty of time for Hurts’ brain to catch up to his arm, and in the meantime his overall passing numbers are just fine — for a freshman, they’re great. (His pass efficiency rating, 142.7, is only slightly behind Jacob Coker’s last year, and slightly ahead of Greg McElroy’s during the 2009 title run.)

Like all Saban quarterbacks, Hurts’ first priority is avoiding unnecessary risks, which he generally does. But it’s no coincidence that most of his big plays as a passer have come on first down, when defenses are more focused on stopping the run, or that his efficiency rating plummets on third-and-long.

On more manageable third downs, though, Hurts has been a machine: With 6 yards or less to go, he’s completed 14 of 19 attempts with 12 conversions — that’s a 63 percent success rate — and zero turnovers. Those are numbers for which Kiffin can personally claim a lot of credit as a play-caller. His commitment to giving his young QB a variety of safe, simple passes to keep the sticks moving is arguably the most overlooked aspect of the team’s success.

Again, here are just a few examples from the last three games, beginning with a pedestrian, 3rd-and-6 swing pass to Harris against Arkansas that, thanks to open-field blocks by Howard (cracking back on a linebacker from the slot) and Cam Robinson (leading the way into the flat from left tackle) winds up going for a 56-yard touchdown on a throw that didn’t even cross the line of scrimmage.

The rest of this genre doesn’t offer as much instant gratification, but the results are eventually the same. Take this routine, 3rd-and-7 swing pass against Tennessee, which ArDarius Stewart advanced for a first down behind a block from Calvin Ridley:

If you watched that game, you might not remember that play. But you certainly remember what happened with the fresh set of downs: Two plays later, Hurts was in the end zone to extend the Tide’s lead to 21-7, and the rout was on.

Or, against Texas A&M, this simple, 3rd-and-5 throw to tailback Joshua Jacobs, a wrinkle off the same swing-pass motion to Stewart that had worked the previous week:

That conversion led to a field goal. On Alabama’s next possession, it faced a 3rd-and-6 from its own 41, and converted again on a well-executed shovel pass to Howard …

… who proceeded to finish off the drive a few plays later with his second touchdown catch of the season from five yards out.

The fact that all of this looks extremely easy is a testament to Alabama’s high skill level across the board, and to Kiffin’s competence as a play-caller. But the larger point is, with a quarterback still in the early stages of the learning curve as a passer, they have been remarkably good at making sure the easy stuff counts.

To Saturday and Beyond.

For an attack that stands to rewrite the school record book, it’s worth reinforcing just how young this group is. Not just Jalen Hurts: Against A&M, only two seniors (O.J. Howard and wide receiver/H-back Gehrig Dieter) saw significant time on offense at all, along with only three juniors — Cam Robinson and Bradley Bozeman on the line and ArDarius Stewart at receiver.

(Another senior starter up front, Alphonse Taylor, sat out for the second straight week due to a concussion; his status remains unclear.)

The rest of the lineup consisted entirely of freshmen and sophomores with at least two years of eligibility remaining beyond 2016. Hurts, Damien Harris, Bo Scarbrough, Calvin Ridley, Jonah Williams, et al, look like they’re only beginning to scratch their potential as a unit, which is a terrifying prospect for opposing defenses even if Hurts doesn’t make great strides as a passer.

More immediately, this weekend’s trip to LSU stands as the toughest test of the season on virtually every level: The Tigers are the best statistical defense Alabama has faced, as well as the most talented, and a night game in Baton Rouge will be the toughest environment Hurts has encountered. (Sorry, Ole Miss and Tennessee: Tiger Stadium is on a level of hostility all its own.)

It’s not difficult to imagine the freshman struggling in situations he hasn’t really faced so far — say, a steady diet of must-pass situations, or attempting to mount a second-half comeback. Hurts has been hit and sacked at various points, but has yet to be consistently pressured throughout any single game. Arden Key can change that.

That said, the next defense that holds the Crimson Tide in check for more than a quarter or two will be the first; eventually, Bama has opened up the floodgates in every game, and in the last three the deluge has begun before halftime. Maybe they’re due for some adversity for a change, as virtually every championship team eventually is at some point along the way. Or maybe they’re just that good.